This article on hardware wallets was originally published at Bruno’s Bitfalls website, and is reproduced here with permission.

One of the most common questions new crypto-enthusiasts have is how hardware wallets like the Ledger Nano S can possibly be the most secure way to store cryptocurrency? What if the device gets stolen or destroyed?

In this post, we’ll try to explain how such a device works in a technical (but hopefully human-readable) way, detailing how it does what it does and how it can be this flexible and yet this secure.

Before we dive into explanations, it’s recommended you read this short post about cryptocurrency wallets, so that the terminology used in the rest of the article becomes clear.

BIP

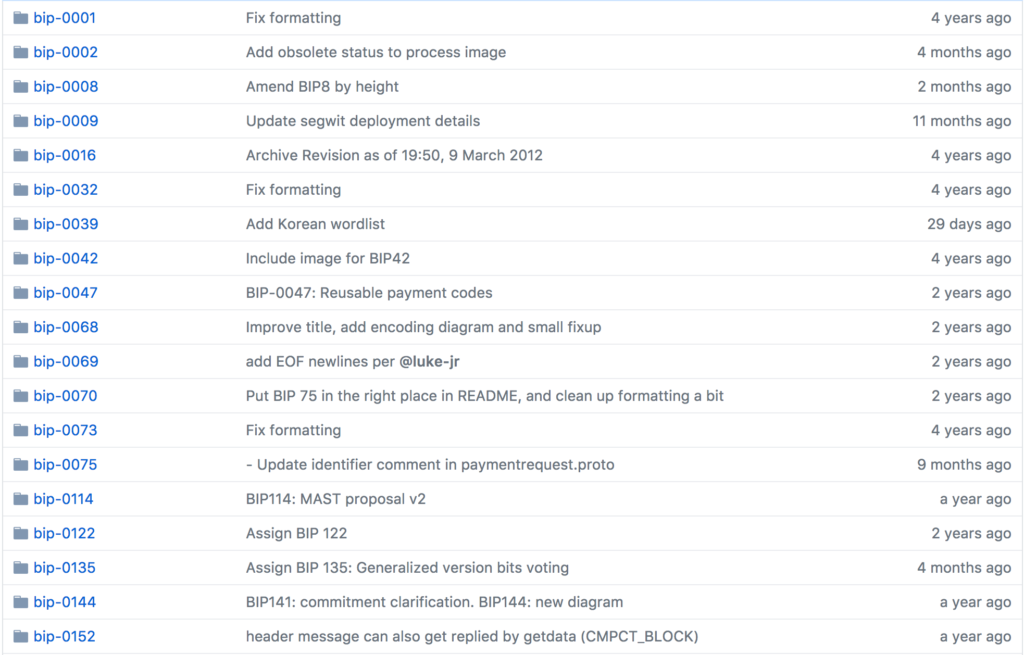

When the blockchain appeared as the technology behind Bitcoin, and a group of programmers/scientists wanted to propose a new feature, they had to formalize and present that idea in a way that’s readable and understandable by all participants of the bitcoin network. Such formal proposals were called Bitcoin Improvement Proposals or BIPs. All BIPs are publicly discussed before being implemented into the blockchain.

By setting up a good foundation for new ideas, this allowed other blockchains to adopt the good ideas that they liked and discard the ones they didn’t.

This is where things get a little more technical and complex. We promise it’ll be worth it by the end of this post — so please keep reading!

One such good idea was BIP 39. BIP 39 uses math to figure out how to use a set of 24 regular words to get a seed — a big random number from which further keys for crypto wallets are later generated.

Curiosity: if you’re interested in taking a look at the lists of supported words, see here.

BIP 39 also defines a way to secure these 24 words with an additional passphrase that counts as word 25. If no passphrase is selected, an empty one is used, so it’s essentially always 24 words + passphrase (empty or not).

Curiosity: this passphrase differs from passwords you’re used to in various interfaces in that it doesn’t produce an error message if the wrong one is used. Any passphrase in combination with 24 words produces a valid seed, which is useful in plausible deniability scenarios – an extortion-protection mechanism we’ll explain later.

This generated seed number is used to generate a root key — an unguessable combination of letters and numbers — for each cryptocurrency you’re interested in. Every blockchain has its own method of generating the root key from the seed, and in the example of bitcoin that’s BIP 32, which results in a key like this one:

xprv9s21ZrQH143K3QTDL4LXw2F7HEK3wJUD2nW2nRk4stbPy6cq3jPPqjiChkVvvNKmPGJxWUtg6LnF5kejMRNNU3TGtRBeJgk33yuGBxrMPHiThis key is then used to generate several private keys, which then become cryptocurrency wallets for a given blockchain.

Confused?

It all boils down to this: BIP 39 is used to pick a certain combination of words, which may or may not be passphrase-protected, which are then used to generate wallets with a formula such as the one described in BIP 32.

So what does all this have to do with a device like the Ledger?

Ledger

When you first turn a Ledger device on, it’ll generate the aforementioned 256-bit seed. This seed number will be used to calculate 24 words which are then shown on the device’s screen.

The user should then write these 24 words down on a piece of paper which comes in the box with the Ledger, and keep that paper safe, away from the Ledger itself.

In addition to that, the Ledger requires the use of a PIN which can have four to eight digits. If, after setting it up, the PIN is wrongly inputted three times in a row, the Ledger will self-destruct all data on it.

Should the Ledger ever get destroyed, stolen, or lost, the original owner of the device can use the words from the piece of paper to restore its contents — either on a backup Ledger, or in a software wallet like MyEtherWallet — thus regaining all funds and addresses. This is possible because all you need to regenerate the root key are those 24 words and the passphrase (if set).

It’s important to say this again: the same root key will always be generated from the same combination of 24 words, and the same addresses will be generated from that root key. Therefore, to reclaim all wallets generated with a BIP 39 word phrase, all you need is the one single combination of 24 words inserted into hardware or software supporting that generation method.

Plausible Deniability

We mentioned extortion-protection previously, so let’s explain it in this section.

The Ledger won’t ask you for your passphrase when you turn it on, but it will ask you for your PIN. The passphrase can’t be set when setting up the device for the first time, either; only in Settings can you subsequently add it.

This lets you attach a separate PIN to a passphrase in order to have two (or more). Each PIN will be bound to its own passphrase, and because of the aforementioned fact that 24 words + passphrase always produce a valid seed (there’s no “Incorrect password” warning), it’s easy to define a decoy PIN to give to someone who’s forcing you to give it up.

In such an instance, inputting the secondary decoy PIN will not destroy the Ledger’s data, but will open wallets corresponding to that passphrase when added to your 24 words. The robber won’t know you haven’t given him the real PIN, and he’ll gain access to bogus addresses. For added effect, add some trivial amounts of cryptocurrency to the addresses to make them seem real; zero-balance addresses won’t be as convincing.

The Probability of Guessing Keys

Many people wonder how easy it would be to just guess the 24 words and gain access to someone’s wallet that way, especially considering BIP 39 isn’t even using the whole dictionary, but only 2048 words.

There are 2256 or 115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007913129639936 possible combinations for the 24 words. If we assume that we have an impossible computer which is capable of guessing 100 trillion combinations a second, to try them all we’d need:

115792089237316195423570985008687907853269984665640564039457584007913129639936 / 100000000000000 = 1157920892373161954235709850086879078532699846656405640394575840 seconds

That’s around 36717430000000000000536992568032848736216424136408984408 years, and that’s only if you have a computer more powerful than anything that’s ever even been imagined by mankind.

What if you know all the words, but not the order? In that case, the number of possible combinations is 24! (24 factorial).

24! = 620448401733239439360000

An equally powerful computer would thus take:

620448401733239439360000 / 100000000000000 = 6204484017 seconds

That’s 196.6 years.

So even if you knew all the words in someone’s combination, but just needed to guess the order, you’d need 200 years of using a computer that’s unimaginably powerful even by today’s standards. If you don’t know which words you need to guess, the number is multiplied by 2048 for every missing word. So not knowing just one of them in this case would increase the time required to guess all combinations to 400,000 years.

Conclusion

The Ledger is an exceptionally safe way of storing your cryptocurrency. It vastly outperforms any kind of USB-based storage where you just save your key into a file and put it away.

The device has its own processor which calculates the keys, which means your root key never leaves the device. This keeps it safe from potential viruses or auto-transacting malware installed on the computer you’re using it with. In addition to that, the Ledger demands an extra hardware confirmation of any transaction: you need to press a button on the device whenever sending funds, or else it doesn’t work. There’s no sneaky funds siphoning with the Ledger.

If you lose or destroy your Ledger, it’s trivial to get all the funds back by just punching in the 24 words obtained when first setting the device up. These words should be kept safe and away from prying eyes.

Bruno is a blockchain developer and technical educator at the Web3 Foundation, the foundation that's building the next generation of the free people's internet. He runs two newsletters you should subscribe to if you're interested in Web3.0: Dot Leap covers ecosystem and tech development of Web3, and NFT Review covers the evolution of the non-fungible token (digital collectibles) ecosystem inside this emerging new web. His current passion project is RMRK.app, the most advanced NFT system in the world, which allows NFTs to own other NFTs, NFTs to react to emotion, NFTs to be governed democratically, and NFTs to be multiple things at once.