Explainer | Huawei extradition battle: The Trump card, the wild card, and Meng Wanzhou’s narrow flight path to freedom

- The final scheduled phase of the tech executive’s epic extradition case is about to begin in Canada, carrying the prospect of her release – or a US trial

- But nothing has been simple about the case, and a tantalising possibility hangs over its closing stages: could a deal be struck outside the court?

On May 27, 2020, a Boeing 777 sat on the tarmac of Vancouver International Airport, ready to take off on a non-stop flight to China.

The jet had been chartered but was so large it could not use the south side of the terminal that is reserved for private flights. Instead, it sat on the reinforced concrete of the north side, alongside commercial airliners.

It was capable of seating 361 passengers, but had been hired by Huawei Technologies (with the help of Chinese diplomats) with only one person in mind: the tech firm’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, who hoped that day to win her court battle to avoid extradition to the US and be released.

It was not to be.

In a key ruling, Associate Chief Justice Heather Holmes of the Supreme Court of British Columbia threw out Meng’s argument that the US fraud case against her failed the extradition requirement of double criminality – that a suspect must be charged with something that would amount to an offence had it been committed in Canada.

It was a heavy blow for Meng, whose extensive getaway plan – described by the head of her security detail in a bail hearing in January – was scrapped. Instead of triumphantly winging her way to Beijing, she returned to her C$13.7million (US$10.9 million) Vancouver mansion, where she remains under partial house arrest.

Major blow to Meng as extradition judge rejects HSBC documents as evidence

Now, Meng’s extradition fight has reached another key juncture, as her lawyers and those of the Canadian justice department, representing US interests in the case, prepare for the final stage of hearings that begin on Wednesday.

This is an extradition proceeding and not a trial, and the presumption is very much in favour of extradition

After those hearings – which could last until August 20 – Holmes will decide again whether to order Meng’s discharge, or to recommend to Canada’s Justice Minister David Lametti that she be extradited to New York to face trial. The minister will make the final decision.

If Meng is released, it would not just signal the end of a marathon case that has drawn worldwide attention. It could be the key to resolving the diplomatic crisis involving Beijing, Ottawa and Washington, that erupted when Meng was arrested at Vancouver’s airport on December 1, 2018.

But nothing about the sprawling case has been simple. And the end game will likely be no exception, with a wild-card prospect hanging over proceedings: could a deal be struck outside the court to free her?

Throwing everything at it

Since last May, and that unused charter flight, arguments in the case have grown expansively, as Meng’s team – composed of some of Canada top lawyers – “throw everything at it”, in the words of University of British Columbia Professor Michael Byers, the Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law.

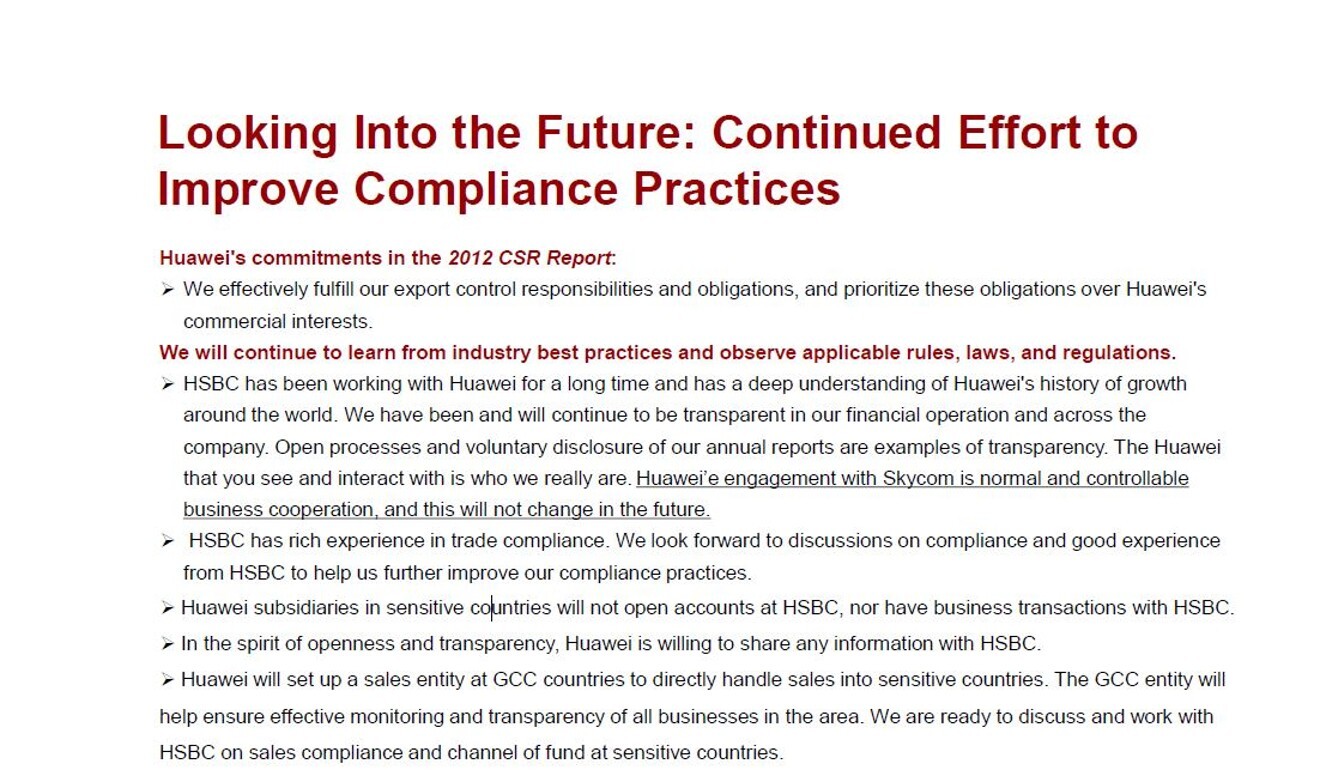

Meng is accused of defrauding HSBC by lying about Huawei’s business dealings in Iran, thus putting the bank at risk of breaching US sanctions.

But 95 per cent of Meng’s arguments “really are not worth the time of day”, Byers said.

“This is an extradition proceeding and not a trial, and the presumption is very much in favour of extradition,” he said.

Although there was a chance Meng could be flying home, Byers thought that it remains unlikely any time soon, and that her path to China is a narrow one.

Gary Botting, a Vancouver barrister who has written several books on extradition law, also said he doubted Holmes would be convinced by any of Meng’s voluminous arguments.

“To be discharged, the individual has to meet a very high standard,” said Botting, who was paid to provide an opinion for Meng in the early stages of the case but is no longer retained by her.

Border agent calls giving police Meng’s passwords a ‘heart-wrenching’ error

That the case had gone on for more than two and a half years was more tribute to the “bottomless pit of resources” available to Meng – a daughter of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei – than her case having numerous routes to success, said Botting, a point on which Byers agreed.

Nevertheless, Holmes will have to assess all her lawyers’ arguments after the final stage of hearings concludes on August 20.

Meng’s case boils down to this: the extradition request should be denied because she is the victim of an abuse of process.

This claim, in turn, consists of four branches.

The first is that the US case is a politically tainted prosecution mounted by former US president Donald Trump to help win his trade war with China.

The second contends that Meng’s treatment by Canadian police and border officers – who questioned her for three hours at Vancouver’s airport before she was told she was going to be arrested – breached her Canadian Charter rights.

The third holds that the US misled the Canadian court by providing it with an unreliable record of the case, while the fourth alleges the prosecution violates international law.

Botting and Byers agreed that Holmes would most likely approve extradition, but differed on how the arguments stacked up, and what might happen next.

“[Holmes’] hands are tied,” said Botting. “She’s going to commit for extradition, probably, so the minister can then do what he should have done in the first place, which is free Madam Meng.”

He said that Meng “can’t possibly get a fair trial in the United States”, and he thought that Lametti would release her “probably on humanitarian grounds, but also because of political interference”.

Byers, however, said he doubted the minister would go against a recommendation to extradite, and should Holmes rule instead that Meng be released, it was “conceivable, but highly unlikely” that the government’s lawyers would not appeal.

For the minister to free Meng against the will of the court might present a way out of the diplomatic crisis with China, but it would then create a problem with the US, “unless there has been some quiet signal from Washington”.

Byers said that whatever the ruling, he believed it would be appealed by the losing side all the way to Canada’s Supreme Court, “and this will continue, and you’ll be reporting on this for at least another couple of years”.

The Trump factor

Seeds of Meng’s case were sown both at the time of her arrest, and in the days that followed.

On December 11, 2018, Donald Trump was asked by the Reuters news agency if he would intervene in her prosecution.

“Whatever is good for the country, I would do,” he said. “If I think it’s good for what will be the largest trade deal ever made – which is a very important thing – what’s good for national security – I would certainly intervene if I thought it was necessary.”

Meng’s lawyers say this and other remarks by US officials prove the case against her is politically tainted, to the extent she must be released.

‘Abhorrent’ Trump remarks take centre stage at Meng extradition hearing

Of the four branches to Meng’s case, these allegations of political interference have drawn the most international scrutiny and popular debate.

“There has been no change in the US position regarding the extradition request,” said Byers, and the absence of reasons to think that Biden was treating the case as political “pushes that whole argument to the side”.

Botting said that although the political aspect was significant, weighing it would probably fall on Lametti, not Holmes.

From Holmes’ likely perspective “I don’t think Trump was in the picture really,” said Botting. “When we talk about bumbling and bungling, there’s a classic example of it … he can be excused for being an idiot.”

‘Keystone Cops’

The second argument suggests that Meng’s treatment by police and border officers violated Section 7 of the Canadian charter of rights – the right to life, liberty and security, and not to be deprived of them except in accordance with principles of fundamental justice.

“I feel this is the only argument that might persuade the judge to set her free,” said Byers. “It’s this one claim, that goes specifically to the fact that she was not told that there was a warrant for her arrest until three hours after she landed, and after three hours of questioning.

“To me, that looks like a violation of Section 7.”

Canadian Mountie at centre of Meng case was elite officer in Hong Kong

The second branch has provided some of the most compelling moments in a courtroom process otherwise dominated by lengthy legal discussion, as a series of Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Canada Border Services Agency officers were questioned and cross-examined about their dealings with Meng. In the hours before her arrest, CBSA officers questioned her about Huawei’s business in Iran and seized her electronic devices and passwords; this had been requested by the US FBI, but the border officers testified it was a normal border process anyway.

A dramatic twist came when a former RCMP sergeant, Ben Chang, refused to testify; it emerged that Chang now works as a casino executive in the Chinese territory of Macau, and the Canadian government’s lawyers said in a legal document there were fears for his safety.

Botting characterised the handling of Meng at the airport as “Keystone Cops action”, attributing dubious procedures to incompetence by the CBSA and RCMP, and “this whole idea of [them] going after big game, when they’re grouse hunting most of the time”.

“So there’s a lot of adrenaline involved with that. Is that excusable? Probably not. But understandable? Probably. To that extent, Holmes is probably going to say ‘well no, this isn’t significant enough to have been an abuse of process’.”

Did the US trick Canada?

The third argument holds that American prosecutors misled the Canadian extradition hearing by providing it with a “manifestly unreliable” record of the case (ROC), a document that summarises the accusations.

An application in this argument will open Wednesday’s proceedings, followed by committal hearings next week.

Among the claims are that the ROC misleadingly depicted a PowerPoint presentation that Meng gave to a HSBC executive at a Hong Kong teahouse in 2013; it is this presentation that lies at the heart of the case.

Has the American prosecution deliberately misstated things? Have they left things out?

Her lawyers have said that contrary to the ROC, HSBC bankers “fully knew” that Huawei Technologies controlled the accounts of affiliates through which it did business in Iran; thus, they said, no fraud could have taken place.

Botting said that if the Americans had in fact misled the Canadian court this was “probably the most relevant thing for Heather Holmes to consider”.

Meng’s lawyers say HSBC ‘fully knew’ about Huawei’s Iran business

“Has the American prosecution deliberately misstated things? Have they left things out?” asked Botting, calling the argument the strongest of the four – although he still doubted it would deter Holmes from approving extradition.

The Americans had wiggle room on the issue, Botting suggested, since the ROC was “meant to be a summary – so there are all kinds of excuses that can be made for leaving out some facts”.

Robert Frater, the Canadian government’s lead lawyer, called the third-branch argument a “distraction” at a March hearing, advising Meng’s team to “save it for the trial”.

Byers concurred. “I come back to the fact this is not a trial,” he said. “As much as it would be concerning if there was documentation to show that the Canadians had been misled, that’s not a matter for extradition.”

And on July 9, the third branch sustained a blow when Holmes ruled that a trove of HSBC documents could not be admitted as evidence in support of the argument.

Why is this a US case?

The fourth branch of Meng’s case argues that the US has no right under international law to prosecute her, and that discussions between a Chinese citizen and a representative of a British bank in a Hong Kong teahouse have nothing to do with the US.

In essence, US laws did not apply in China, Meng’s lawyer Gib van Ert said at a hearing in March, and Canada had a duty to protect her from the US attempt to violate international law.

Again, Byers said this matter was one for a trial judge to consider, not Holmes.

‘US laws do not apply in China’: new front opens in Meng extradition fight

Successive Canadian governments had held that the US legal system could be trusted to behave in a “professional and rights-respecting way”.

“That’s why we have … this presumption in favour of extradition. It’s a mutual recognition, and mutual respect of the legal systems of the two countries,” he said.

Botting agreed that “International law doesn’t figure at the committal stage”, adding “I can’t see how it is a violation of international law”.

The wild card

Looming tantalisingly over the case is the possibility that a deal struck outside the Canadian court process could resolve the issue, regardless of what Holmes decides.

In December, The Wall Street Journal reported that the US was negotiating with Meng about a deferred prosecution agreement to allow her to return to China. Under such a deal, a suspect typically admits wrongdoing and may offer other cooperation in exchange for charges being dropped in the future.

If I were in David Lametti’s or Justin Trudeau’s shoes, I’d say, ‘let’s show the world that our system is not politicised, and let Ms Meng benefit from all of the opportunities available to an accused’

Botting said the only deal that would make sense for Meng would be one in which her name was removed from the US indictment – otherwise she would remain “in jeopardy” whenever she travelled outside China.

And if she tried to strike a plea deal, “whatever deal you make with the police or the assistant US attorney, it’s going to be up to the [US] judge. The judge could say, ‘well, that’s ridiculous’, and impose a jail sentence anyway”.

US deal for Meng Wanzhou could be a trap, says extradition expert

Last May, Meng was so confident of heading home that she took part in a pre-victory photo shoot on the steps of the courthouse a few days ahead of Holmes’ double-criminality ruling. She and her entourage flashed thumbs-up and V-for-victory signs for a photographer standing on a step ladder.

But now Meng may have concluded that her best hope is simply to delay extradition as long as possible, to provide more time for the political landscape to change, said Byers.

“There may emerge some reason for the Canadian and the Chinese governments to improve their relations that we can’t anticipate,” he said. “There could be a change of government in Ottawa. There are a lot of unforeseen events that could occur that could work in Ms Meng’s favour if she is still in Canada.”

Her vast resources had led to a highly unusual scenario, he said.

“Usually, extradition happens quickly. But she is taking advantage of our rule-of-law system, and she’s doing so at a time when they still have the two Michaels in China,” said Byers, referring to the Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, who were arrested by China in the days after Meng’s arrest and were tried for espionage this year.

Verdicts have not been announced; Canada regards Kovrig and Spavor as victims of arbitrary detention and hostage diplomacy.

“So there’s all kinds of ironies there,” said Byers. “But if I were in David Lametti’s or Justin Trudeau’s shoes, I’d say, ‘let’s show the world that our system is not politicised, and let Ms Meng benefit from all of the opportunities available to an accused’.”