Abstract

Financial toxicity is a broad term to describe the economic consequences and subjective burden resulting from a cancer diagnosis and treatment. As financial toxicity is associated with poor disease outcomes, recognition of this problem and calls for strategies to identify and support those most at risk are increasing. Men with localized prostate cancer face treatment choices including active surveillance, prostatectomy or radiotherapy. The fact that potential patient out-of-pocket costs might influence decision making has rarely been acknowledged and, overall, the risk of financial toxicity for men with localized prostate cancer remains poorly studied. This shortfall requires a work-up in the context of prostate cancer and a multidimensional framework for considering a patient’s risk of financial toxicity. The major elements of this framework are direct and indirect costs, patient-specific values, expectations of possible financial burdens, and individual economic circumstances. Current data indicate that total cost patterns probably differ by treatment modality: surgery might have an increased short-term effect, whereas radiotherapy might have an increased long-term risk of financial toxicity. Specific thresholds of patient income levels or out-of-pocket costs that predict risk of financial toxicity are difficult to identify. Compared with other malignancies, prostate cancer might have a lower overall risk of financial toxicity, but persistent post-treatment urinary, bowel or sexual adverse effects are likely to increase this risk.

Key points

The term financial toxicity broadly reflects the financial consequences and subjective burden resulting from a cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Financial toxicity is increasingly recognized in oncology but has been poorly studied in the context of prostate cancer.

A high risk of developing financial distress might influence a patient’s treatment decisions; however, no guidelines recommend explicit discussion of this topic.

A patient’s risk of developing financial toxicity is multifactorial and is likely to be influenced by direct costs, indirect costs, patient-specific values and expectations of possible financial burdens, as well as individual economic circumstances.

The risk of developing financial toxicity probably differs depending on the treatment approach: surgery might particularly influence short-term risk and radiotherapy might influence long-term risk.

The overall risk of financial toxicity might be lower for men with prostate cancer than for men with other cancers; however, men with persistent treatment-related adverse effects are likely to be at higher risk.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Institutes of Health. Cancer stat facts: prostate cancer. National Cancer Institute SEER https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html (2018).

Noone A. M. et al. (eds). SEER cancer statistics review (CSR) 1975–2015. National Cancer Institute SEER https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/ (2018).

Epstein, J. I. et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 40, 244–252 (2016).

Mohler, J. L. et al. Prostate cancer, version 2.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 17, 479–505 (2019).

Showalter, T. N., Mishra, M. V. & Bridges, J. F. Factors that influence patient preferences for prostate cancer management options: a systematic review. Patient Prefer. Adherence 9, 899–911 (2015).

Sidana, A. et al. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: what younger men choose and why. Prostate 72, 58–64 (2012).

Xu, J., Dailey, R. K., Eggly, S., Neale, A. V. & Schwartz, K. L. Men’s perspectives on selecting their prostate cancer treatment. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 103, 468–478 (2011).

Bosco, J. L. F., Halpenny, B. & Berry, D. L. Personal preferences and discordant prostate cancer treatment choice in an intervention trial of men newly diagnosed with localized prostate cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10, 123 (2012).

Zafar, S. Y. & Abernethy, A. P. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology 27, 80–149 (2013).

Meropol, N. J. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 3868–3874 (2009).

Schroeck, F. R. et al. Cost of new technologies in prostate cancer treatment: systematic review of costs and cost effectiveness of robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy, and proton beam therapy. Eur. Urol. 72, 712–735 (2017).

Hartman, M., Martin, A. B., Espinosa, N. & Catlin, A., The National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National health care spending in 2016: spending and enrollment growth slow after initial coverage expansions. Health Aff. 37, 150–160 (2017).

Gilligan, A. M., Alberts, D. S., Roe, D. J. & Skrepnek, G. H. Death or debt? National estimates of financial toxicity in persons with newly-diagnosed cancer. Am. J. Med. 131, 1187–1199.e5 (2018).

Gordon, L. G., Merollini, K. M. D., Lowe, A. & Chan, R. J. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can’t pay the co-pay. Patient 10, 295–309 (2017).

Lathan, C. S. et al. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 1732–1740 (2016).

Sharp, L., Carsin, A.-E. & Timmons, A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology 22, 745–755 (2013).

Meeker, C. R. et al. Relationships among financial distress, emotional distress, and overall distress in insured patients with cancer. J. Oncol. Pract. 12, e755–e764 (2016).

Fenn, K. M. et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J. Oncol. Pract. 10, 332–338 (2014).

Zafar, S. Y. et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J. Oncol. Pract. 11, 145–150 (2015).

Ramsey, S. D. et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 980–986 (2016).

Zafar, S. Y. et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist 18, 381–390 (2013).

Kaisaeng, N., Harpe, S. E. & Carroll, N. V. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 20, 669–675 (2014).

Hess, L. M. et al. Factors associated with adherence to and treatment duration of erlotinib among patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 23, 643–652 (2017).

Marchetti, B., Spinola, P. G., Pelletier, G. & Labrie, F. A potential role for catecholamines in the development and progression of carcinogen-induced mammary tumors: hormonal control of beta-adrenergic receptors and correlation with tumor growth. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 307–320 (1991).

Zhao, X. Y. et al. Glucocorticoids can promote androgen-independent growth of prostate cancer cells through a mutated androgen receptor. Nat. Med. 6, 703–706 (2000).

Thaker, P. H. et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Med. 12, 939–944 (2006).

Sood, A. K. et al. Stress hormone-mediated invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 369–375 (2006).

Thaker, P. H., Lutgendorf, S. K. & Sood, A. K. The neuroendocrine impact of chronic stress on cancer. Cell Cycle 6, 430–433 (2007).

Lin, J., Epel, E. & Blackburn, E. Telomeres and lifestyle factors: roles in cellular aging. Mutat. Res. 730, 85–89 (2012).

Graham, M. K. & Meeker, A. Telomeres and telomerase in prostate cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 14, 607–619 (2017).

Bullock, A. J., Hofstatter, E. W., Yushak, M. L. & Buss, M. K. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J. Oncol. Pract. 8, e50–e58 (2012).

Shih, Y.-C. T. & Chien, C.-R. A review of cost communication in oncology: patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcome assessment. Cancer 123, 928–939 (2017).

Jagsi, R. et al. Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 124, 3668–3676 (2018).

Faiena, I. et al. Regional cost variations of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy compared with open radical prostatectomy. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 13, 447–452 (2015).

Parthan, A. et al. Comparative cost-effectiveness of stereotactic body radiation therapy versus intensity-modulated and proton radiation therapy for localized prostate cancer. Front. Oncol. 2, 81 (2012).

Claxton, G., Rae, M., Long, M., Damico, A. & Whitmore, H. Health benefits in 2018: modest growth in premiums, higher worker contributions at firms with more low-wage workers. Health Aff. 37, 1892–1900 (2018).

James, N. D. et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 338–351 (2017).

Rapiti, E. et al. Impact of socioeconomic status on prostate cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Cancer 115, 5556–5565 (2009).

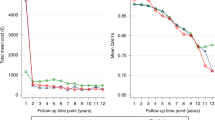

Tang, J. et al. Longitudinal comparison of patient-level outcomes and costs across prostate cancer treatments with urinary problems. Am. J. Mens. Health 13, (2019).

Fryback, D. G. & Craig, B. M. Measuring economic outcomes of cancer. JNCI Monogr. 2004, 134–141 (2004).

Jayadevappa, R. et al. The burden of out-of-pocket and indirect costs of prostate cancer. Prostate 70, 1255–1264 (2010).

Yousuf Zafar, S. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it’s time to intervene. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108, djv370 (2016).

Rotter, J., Spencer, J. C. & Wheeler, S. B. Financial toxicity in advanced and metastatic cancer: overburdened and underprepared. J. Oncol. Pract. 15, e300–e307 (2019).

Koopmanschap, M. A. & Rutten, F. F. Indirect costs in economic studies: confronting the confusion. Pharmacoeconomics 4, 446–454 (1993).

Chino, F. et al. Going for broke: a longitudinal study of patient-reported financial sacrifice in cancer care. J. Oncol. Pract. 14, e533–e546 (2018).

Hunter, W. G. et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 108 (2016).

Chino, F. et al. Out-of-pocket costs, financial distress, and underinsurance in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1582–1584 (2017).

Henrikson, N. B., Tuzzio, L., Loggers, E. T., Miyoshi, J. & Buist, D. S. Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support. Care Cancer 22, 961–967 (2014).

Zafar, S. Y. et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am. J. Manag. Care 21, 607–615 (2015).

Jung, O. S. et al. Out-of-pocket expenses and treatment choice for men with prostate cancer. Urology 80, 1252–1257 (2012).

de Souza, J. A. et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer 120, 3245–3253 (2014).

Prawitz, A. et al. Incharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 17, 2239338 (2006).

Huntington, S. F. et al. Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol. 2, e408–e416 (2015).

de Souza, J. A. et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123, 476–484 (2017).

Yabroff, K. R., Lund, J., Kepka, D. & Mariotto, A. Economic burden of cancer in the US: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 20, 2006–2014 (2011).

Eibner, C. & Nowak, S. The effect of eliminating the individual mandate penalty and the role of behavioral factors. The Commonwealth Fund https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2018/jul/eliminating-individual-mandate-penalty-behavioral-factors (2018).

Laviana, A. A. et al. Utilizing time-driven activity-based costing to understand the short- and long-term costs of treating localized, low-risk prostate cancer. Cancer 122, 447–455 (2016).

Pate, S. C., Uhlman, M. A., Rosenthal, J. A., Cram, P. & Erickson, B. A. Variations in the open market costs for prostate cancer surgery: a survey of US hospitals. Urology 83, 626–630 (2014).

Kishan, A. U. & King, C. R. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 27, 268–278 (2017).

Pan, H. Y. et al. Comparative toxicities and cost of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, proton radiation, and stereotactic body radiotherapy among younger men with prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 36, 1823–1830 (2018).

Chuong, M. D. et al. Minimal toxicity after proton beam therapy for prostate and pelvic nodal irradiation: results from the Proton Collaborative Group REG001-09 trial. Acta Oncol. Stockh. Swed. 57, 368–374 (2018).

Dess, R. T. et al. The current state of randomized clinical trial evidence for prostate brachytherapy. Urol. Oncol. 37, 599–610 (2019).

Lanni, T. et al. Comparing the cost-effectiveness of low-dose-rate brachytherapy, high-dose-rate brachytherapy, and hypofactionated intensity modulated radiation therapy for the treatment of low-/intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 90, S587–S588 (2014).

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey – section 7: employee cost sharing. KFF https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2017-section-7-employee-cost-sharing/ (2017).

Zheng, Z. et al. Annual medical expenditure and productivity loss among colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancer survivors in the United States. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108, (2015).

Markman, M. & Luce, R. Impact of the cost of cancer treatment: an internet-based survey. J. Oncol. Pract. 6, 69–73 (2010).

Davidoff, A. J. et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer 119, 1257–1265 (2013).

Gordon, L. G. et al. Financial toxicity: a potential side effect of prostate cancer treatment among Australian men. Eur. J. Cancer Care 26, e12392 (2017).

Housser, E. et al. Responses by breast and prostate cancer patients to out-of-pocket costs in Newfoundland and Labrador. Curr. Oncol. 20, 158–165 (2013).

Sharp, L. & Timmons, A. Pre-diagnosis employment status and financial circumstances predict cancer-related financial stress and strain among breast and prostate cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 24, 699–709 (2016).

Carter, H. B. et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline. J. Urol. 190, 419–426 (2013).

Mehnert, A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 77, 109–130 (2011).

Bradley, C. J., Neumark, D., Luo, Z., Bednarek, H. & Schenk, M. Employment outcomes of men treated for prostate cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 97, 958–965 (2005).

Ratcliffe, J. The measurement of indirect costs and benefits in health care evaluation: a critical review. Proj. Apprais. 10, 13–18 (1995).

Bradley, C. J., Oberst, K. & Schenk, M. Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psychooncology 15, 739–747 (2006).

Yabroff, K. R. & Kim, Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer 115, 4362–4373 (2009).

Li, C. et al. Burden among partner caregivers of patients diagnosed with localized prostate cancer within 1 year after diagnosis: an economic perspective. Support. Care Cancer 21, 3461–3469 (2013).

de Oliveira, C. et al. Patient time and out-of-pocket costs for long-term prostate cancer survivors in Ontario, Canada. J. Cancer Surviv. Res. Pract. 8, 9–20 (2014).

Kleinert, S. & Horton, R. Health in Europe–successes, failures, and new challenges. Lancet 381, 1073–1074 (2013).

ChartsBin. Universal health care around the world. ChartsBin http://chartsbin.com/view/z1a (2010).

Mahal, B. A. et al. Travel distance and stereotactic body radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Cancer 124, 1141–1149 (2018).

Burns, R., Wolstenholme, J., Leslie, T. & Hamdy, F. Enhancing prostate cancer trial design by incorporating robust economic analysis: lessons learned from the UK part feasibility study [abstract]. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 44, S33 (2018).

Bouwmans, C. et al. The iMTA productivity cost questionnaire: a standardized instrument for measuring and valuing health-related productivity losses. Value Health 18, 753–758 (2015).

Federal Reserve System. Survey of consumer finances (SCF). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System https://federalreserve.gov/econres/scfindex.htm (2016).

Sanda, M. G. et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 1250–1261 (2008).

Attkisson, C. C. & Greenfield, T. K. in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcomes Assessment: Instruments for Adults 3rd edn Vol. 3 (ed. Maruish, M.E.) 799–811 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2004).

Brazier, J. E. et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 305, 160–164 (1992).

Litwin, M. S. et al. The UCLA Prostate Cancer Index: development, reliability, and validity of a health-related quality of life measure. Med. Care 36, 1002–1012 (1998).

Jayadevappa, R., Schwartz, J. S., Chhatre, S., Wein, A. J. & Malkowicz, S. B. Satisfaction with care: a measure of quality of care in prostate cancer patients. Med. Decis. Mak. 30, 234–245 (2010).

Wollins, D. S. & Zafar, S. Y. A touchy subject: can physicians improve value by discussing costs and clinical benefits with patients? Oncologist 21, 1157–1160 (2016).

Sanda, M. G. et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Part I: risk stratification, shared decision making, and care options. J. Urol. 199, 683–690 (2018).

Mossanen, M. & Smith, A. B. Addressing financial toxicity: the role of the urologist. J. Urol. 200, 43–45 (2018).

Schrag, D. & Hanger, M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 233–237 (2007).

Hunter, W. G. et al. Discussing health care expenses in the oncology clinic: analysis of cost conversations in outpatient encounters. J. Oncol. Pract. 13, e944–e956 (2017).

Kelly, R. J. et al. Patients and physicians can discuss costs of cancer treatment in the clinic. J. Oncol. Pract. 11, 308–312 (2015).

Zafar, S. Y. & Abernethy, A. P. Financial toxicity, part II: how can we help with the burden of treatment-related costs? Oncology 27, 253–254, 256 (2013).

Zafar, S. Y., Newcomer, L. N., McCarthy, J., Fuld Nasso, S. & Saltz, L. B. How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? One shot, four perspectives. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 37, 35–39 (2017).

Tran, G. & Zafar, S. Y. Financial toxicity and implications for cancer care in the era of molecular and immune therapies. Ann. Transl. Med. 6, 166 (2018).

Teckie, S., Rudin, B., Chou, H., Stanzione, R. & Potters, L. Creation of an episode-based payment model for prostate and breast cancer radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 99, E417–E418 (2017).

Ellimoottil, C. et al. Episode-based payment variation for urologic cancer surgery. Urology 111, 78–85 (2018).

Obama, B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA 316, 525–532 (2016).

Hayes, S. L., Collins, S. R. & Radley, D. C. How much U.S. households with employer insurance spend on premiums and out-of-pocket costs: a state-by-state look. The Commonwealth Fund https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2019/may/how-much-us-households-employer-insurance-spend-premiums-out-of-pocket (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Goldberg, MSLIS, for graciously assisting with our research database queries and for providing suggestions on literature review best practices. B.S.I. received a Resident Seed Grant from the American College of Radiation Oncology (ACRO) to perform the literature research for this Review. The Review was also funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Review criteria

Electronic searches of several research databases, including PubMed and the Cochrane Library, were conducted. A search strategy was developed in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian. The search string was initially developed for PubMed and later adapted for other databases. It was restricted to English language publications but not by date of publication. The research goal was to clarify the prevalence and potential drivers of patient-level financial strain for men diagnosed with non-metastatic prostate cancer. The search string was purposely broad given our experience that heterogeneous descriptors are often used in the literature. No restrictions were made regarding non-empirical studies, such as literature reviews or conference abstracts. Titles of identified studies were then manually screened followed by a secondary abstract review to ensure relevance to our research objective. Finally, following full-text review of selected sources, the references were cross-referenced with the database results to identify additional potentially relevant resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.I. and M.V. researched data for the article. B.S.I., M.V., B.E. and D.G. made substantial contributions to the discussion of the article content. B.S.I., B.E. and D.G. wrote the manuscript. B.S.I., M.V., B.E. and D.G. reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.E. is a speaker to the Myriad Genetics Inc Medical Advisory Board and is the Principal Investigator of a phase 2 trial of MR-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer. B.S.I., M.V. and D.G. declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Urology thanks E. Onukwugha and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Financial toxicity

-

A comprehensive term for the patient harm caused by the direct and indirect costs of cancer treatment.

- Payor

-

The private or public entities that pay for health-care services. Examples include private insurance companies or a government-supported single public system (for example, the National Health Service in the UK).

- Deductibles

-

The total out-of-pocket annual health-care expenses that patients must accrue before the insurance coverage activates and the payor begins to pay some (or all) of the remaining costs for that calendar year (usually a fixed annual monetary amount; for example $1,000).

- Co-payments

-

Fixed, out-of-pocket monetary amounts that patients are required to pay by their insurer for a particular health-care service such as a physician visit or a prescription drug.

- Co-insurance

-

The amount of a total health-care cost that patients are responsible for paying after they have met their deductible (usually a fixed percentage; for example, 20%); the payor will pay the remaining portion of the cost.

- Opportunity costs

-

The financial or other benefits a person misses out on by choosing one alternative over another (in the context of working, opportunity costs could reflect the lost wages from days not worked owing to illness).

- Member cost-sharing

-

Features of insurance plans that are designed to distribute some of the fees billed for health care to beneficiaries (for example, deductibles, co-payments and co-insurance models).

- Supplemental insurance

-

Extra or additional insurance that a person can obtain to cover some of the out-of-pocket health-care expenses not covered by the primary insurance plan.

- Likert scale

-

A psychometric tool frequently used in surveys that ask respondents to state their level of agreement or frequency using predefined criteria (for example, agree, strongly agree, etc.).

- Affordable Care Act

-

Also known as the ACA, PPACA or Obamacare. A comprehensive US health-care reform law passed in 2010 that contained several provisions, including the requirement that US citizens obtain health insurance or face a tax (known as the individual mandate).

- Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

-

A set of US-wide surveys of individuals and families, their medical providers, and employers, providing one of the most complete data sources for the cost and use of health care and health insurance coverage in the USA.

- Premium

-

The annual amount to be paid for an insurance policy.

- Human capital approach

-

A commonly used labour economic strategy to estimate indirect costs that assumes that lost earnings are a proxy for lost output and generally multiplies incremental time lost from employment by wage per unit time.

- Bundled payment

-

A financial reimbursement model in which a physician or health-care system is paid a single sum for an entire episode of care, not individual sums for each specific service provided.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imber, B.S., Varghese, M., Ehdaie, B. et al. Financial toxicity associated with treatment of localized prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol 17, 28–40 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0258-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41585-019-0258-3

This article is cited by

-

Subjective and objective financial toxicity among colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review

BMC Cancer (2024)

-

Treatment-Related Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Prostate Cancer: Patients’ Real-World Insights for Optimizing Outcomes

Advances in Therapy (2024)

-

Associations of financial toxicity with symptoms and unplanned healthcare utilization among cancer patients taking oral chemotherapy at home: a prospective observational study

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Aspartoacylase suppresses prostate cancer progression by blocking LYN activation

Military Medical Research (2023)

-

A randomized phase II trial of MR-guided prostate stereotactic body radiotherapy administered in 5 or 2 fractions for localized prostate cancer (FORT)

BMC Cancer (2023)