Carefully stacking and rotating two honeycomb-shaped lattices of carbon to a special angle generates a new kind of magnetism, which scientists had predicted but not yet observed.

The authors suggest the magnetism, called orbital ferromagnetism, could prove useful for certain applications, such as quantum computing.

“We were not aiming for magnetism. We found what may be the most exciting thing in my career to date through partially targeted and partially accidental exploration,” says study leader David Goldhaber-Gordon, a professor of physics at Stanford University. “Our discovery shows that the most interesting things turn out to be surprises sometimes.”

The researchers inadvertently made their discovery while trying to reproduce a finding that was sending shockwaves through the physics community. In early 2018, Pablo Jarillo-Herrero’s group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology announced that they had coaxed a stack of two subtly misaligned sheets of carbon atoms—twisted bilayer graphene—to conduct electricity without resistance, a property known as superconductivity.

The discovery was a stunning confirmation of a nearly decade-old prediction that graphene sheets rotated to a very particular angle should exhibit interesting phenomena.

When stacked and twisted, graphene forms a superlattice with a repeating interference, or moiré, pattern. “It’s like when you play two musical tones that are slightly different frequencies,” Goldhaber-Gordon says. “You’ll get a beat between the two that’s related to the difference between their frequencies. That’s similar to what you get if you stack two lattices atop each other and twist them so they’re not perfectly aligned.”

Physicists theorized that the particular superlattice formed when graphene is rotated to 1.1 degrees causes the normally varied energy states of electrons in the material to collapse, creating what they call a flat band where the speed at which electrons move drops to nearly zero. Thus slowed, the motions of any one electron becomes highly dependent on those of others in its vicinity. These interactions lie at the heart of many exotic quantum states of matter.

“I thought the discovery of superconductivity in this system was amazing. It was more than anyone had a right to expect,” Goldhaber-Gordon says. “But I also felt that there was a lot more to explore and many more questions to answer, so we set out to try to reproduce the work and then see how we could build upon it.”

Graphene with a twist

While attempting to duplicate the MIT team’s results, Goldhaber-Gordon and his group introduced two seemingly unimportant changes.

First, while encapsulating the honeycomb-shaped carbon lattices in thin layers of hexagonal boron nitride, the researchers inadvertently rotated one of the protective layers into near alignment with the twisted bilayer graphene.

“It turns out that if you nearly align the boron nitride lattice with the lattice of the graphene, you dramatically change the electrical properties of the twisted bilayer graphene,” says co-first author Aaron Sharpe, a graduate student in Goldhaber-Gordon’s lab.

Secondly, the group intentionally overshot the angle of rotation between the two graphene sheets. Instead of 1.1 degrees, they aimed for 1.17 degrees because others had recently shown that twisted graphene sheets tend to settle into smaller angles during the manufacturing process.

“We figured if we aim for 1.17 degrees, then it will go back toward 1.1 degrees, and we’ll be happy,” Goldhaber-Gordon says. “Instead, we got 1.2 degrees.”

Orbital ferromagnetism

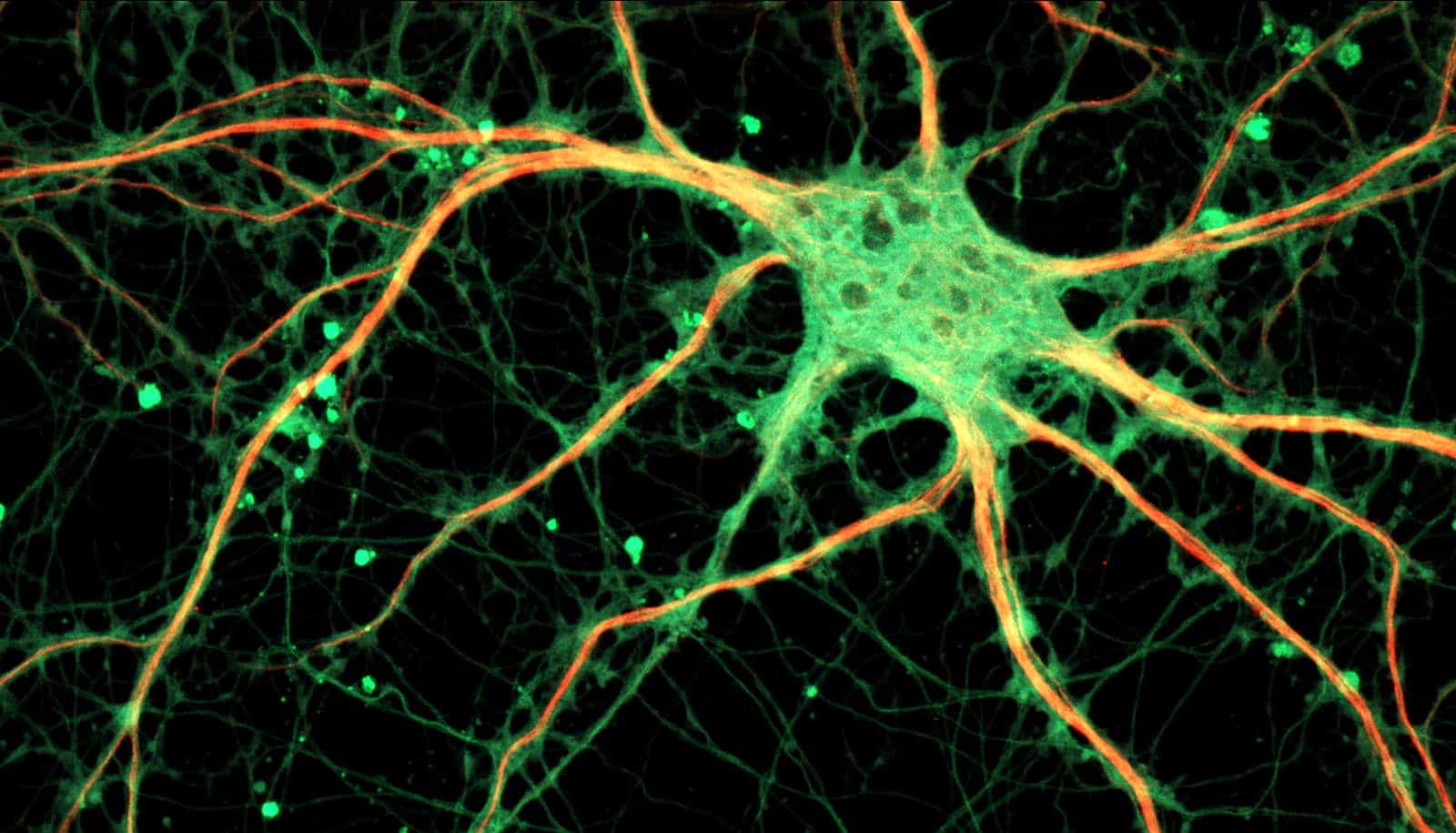

The consequences of these small changes didn’t become apparent until the researchers began testing the properties of their twisted graphene sample. In particular, they wanted to study how its magnetic properties changed as its flat band—that collection of states where electrons slow to nearly zero—was filled or emptied of electrons.

While pumping electrons into a sample that researchers had cooled close to absolute zero, Sharpe detected a large electrical voltage perpendicular to the flow of the current when the flat band was three-quarters full. Known as a Hall voltage, such a voltage typically only appears in the presence of an external magnetic field—but in this case, the voltage persisted even after researchers had switched off the external magnetic field.

Researchers could only explain this anomalous Hall effect if the graphene sample was generating its own internal magnetic field. Furthermore, this magnetic field couldn’t be the result of aligning the up or down spin state of electrons, as is typically the case for magnetic materials, but instead must have arisen from their coordinated orbital motions.

“To our knowledge, this is the first known example of orbital ferromagnetism in a material,” Goldhaber-Gordon says. “If the magnetism were due to spin polarization, you wouldn’t expect to see a Hall effect. We not only see a Hall effect, but a huge Hall effect.”

Weak, but powerful

The researchers estimate that the magnetic field near the surface of their twisted graphene sample is about a million times weaker than that of a conventional refrigerator magnet, but this weakness could be a strength in certain scenarios, such as building memory for quantum computers.

“Our magnetic bilayer graphene can be switched on with very low power and can be read electronically very easily,” Goldhaber-Gordon says. “The fact that there’s not a large magnetic field extending outward from the material means you can pack magnetic bits very close together without worrying about interference.”

Goldhaber-Gordon’s lab isn’t done exploring twisted bilayer graphene yet. The group plans to make more samples using recently improved fabrication techniques in order to further investigate the orbital magnetism.

The research appears in issue of the journal Science. Additional researchers from Stanford and the National Institute for Materials Science in Japan were also involved in the work. Funding came from the US Department of Energy, the ARCS Foundation, the Elemental Strategy Initiative, the Ford Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Source: Stanford University