For all the identifiers that obituary writers will reach for to describe Bill Wittliff—screenwriter, photographer, book publisher, novelist, sketch artist, archivist, preservationist, champion of the arts, man of letters—two things are important to remember. First off, Wittliff himself, constitutionally untucked and simple, could have shorthanded that list with one apt word: storyteller. But more to the point, as significant as his best-known achievements are—he wrote and co-produced the television version of Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, the best Western ever filmed; he founded and guided, with his wife, Sally, the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University in San Marcos, the world’s finest repository of Southwestern writing, photography, and culture—the first thing that came to mind when folks who knew him learned he’d died was something else entirely. He was a great friend.

So on Monday, the day after Wittliff died of a heart attack in Austin at 79, I called Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones. That’s not to suggest that calling them is something I do often or, actually, ever. I don’t know those people. But we were each close with Wittliff. They got to know him when they gave flesh and blood to Augustus McRae and Woodrow Call as McMurtry and Wittliff had written them. And I became his friend when I performed the much lesser task of chronicling the creation of Lonesome Dove for a 2010 Texas Monthly story, which was later expanded into A Book on the Making of Lonesome Dove. But such was the nature of a connection to Wittliff that when one of his friends rings up another to talk Bill, the call is taken.

Duvall wanted to talk about movies. “Lonesome Dove was The Godfather of Westerns,” he began, a comparison he’s made frequently and, as a co-star of both, with unique authority. “He wrote a wonderful script from a marvelous novel. I love to improvise, but there was no real room for that because the script was so well done. Wherever I go now, Europe or wherever, people mention Lonesome Dove more than anything else I ever did.” Then he brought up another Wittliff film, 2013’s A Night in Old Mexico. It was a script Wittliff had been trying to make with Duvall for 25 years. He’d written it for the actor, who portrayed an irascible, old West Texas rancher who takes his teenaged grandson on a sudden road trip to the border, complete with a bordello, gunplay, and a bag of stolen drug money. “It was a legitimate shadow of Lonesome Dove. An extension. The two parts were kind of cousins. But it didn’t make the same impact. Lonesome Dove just struck a chord. Five hundred years from now it will still be around.”

Jones, on the other hand, who is generally thought to share many qualities with the ramrod Call, had much more to say. He wanted to talk about the man. “When we were making Lonesome Dove and becoming friends, Bill liked to talk about fly-fishing. He was very proud of this arcane craft he had developed. I had pulled a lot of catfish off a lot of trotlines, but I didn’t know anything about fly-fishing. He piqued my enthusiasm. Two days after we wrapped, he talked me into a fishing trip.”

Filming had wound down in northern New Mexico, so they took to the San Juan River, just below Navajo Dam. Wittliff chose the spot for convenience, not the quality of the fish, which was lacking. He brought along his son, Reid, a UT sophomore who’d worked the production, as well as a friend, the writer John Graves, whose 1960 travel memoir Goodbye to a River is a classic of conservationism and naturalist philosophy. It’s Texas’s Walden.

“I’d read all of John’s work,” Jones continued. “I think he was one of our finest prose stylists in the 20th century in Texas. And that started my life as a fly-fisherman. The fish were old, wore-out trout. They’d been caught and released so many times that the corners of their mouths were all scored. But it was a wonder for me. The thinking of a fly-fisherman was a brave new world. And”—thanks to Wittliff—“I was learning by the minute in the presence of a master, John Graves. It was one of the most generous things that a very generous man ever did for me.”

Their friendship grew for thirty years. They worked for a decade on a screen adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s Islands in the Stream, trading drafts, scouting locations, and looking for money. But much of their time together was occasioned by impromptu appearances by Jones in the doorway of Wittliff’s Austin office. Jones drives frequently from his San Antonio home to a ranch in San Saba County where he raises horses and cattle. “Sometimes I’d go a little bit out of the way to get some enchiladas with Bill and talk about whatever there was to talk about. I loved making Lonesome Dove, but I didn’t realize until years later how lucky I was to know him. I valued him greatly as a friend.”

Jones first became aware of Bill Wittliff the way most people did in the sixties and seventies, through Encino Press. Bill and Sally, his college sweetheart, started the small publishing house in the second bedroom of their Dallas apartment not long after marrying in 1963. Soon they moved to Austin and ran it from their carport. They focused on books about Texas and the Southwest, and built a following on the strength of Wittliff’s editing, illustration, and book design. In 1968 he published Larry McMurtry’s first collection of essays, In a Narrow Grave, arguably the best thinking on the essence of Texas that’s ever been put to paper. It was hardly all positive, which Wittliff liked to say caught them both a lot of hell. If publishing that book had been the only thing he ever did, the state would owe him a huge debt.

But the magic of Wittliff was that he never stood still. He always had something simmering on a back burner, some project to mull, new craft to learn, or relationship to cultivate that might not be realized for decades. While Encino Press was scraping to get going—and he and Sally were having their kids, Reid and Allison—he was teaching himself photography. He then spent three years off and on in the early seventies chronicling roundups on a sprawling ranch in northern Mexico. The images, already a gritty look back in time when he took them, hit even stronger when UT Press published them as a coffee table book, Vaquero: Genesis of the Texas Cowboy, in 2004, with an introduction by Graves.

I asked Jones about Wittliff’s photography. “I like the pictures he made from the negatives he found behind that whorehouse in Nuevo Laredo,” he said. That was another long-term project. In the mid-seventies, Wittliff met a photographer who took souvenir pictures in Boystown bars of down-and-out prostitutes and the men who brought them business, many from across the Rio Grande. Wittliff visited the photographer’s darkroom, found thousands of deteriorating negatives, talked him into selling them, and smuggled them into Texas. For the next 25 years he’d occasionally grab up a handful and devote hours to their cleaning and printing.

Aperture published that series in a 2000 book, Boystown: La Zona de Tolerancia, with an essay by art critic Dave Hickey. The images are striking, scenes from an unjust milieu. In some shots you can almost hear the frat boys giggling. But something in Wittliff’s curation and presentation focuses the eye on the quiet strength of the women. “You could say the subject matter is trashy,” said Jones, “that the photography is done in a trashy manner by trashy shooters, that the negatives became trash. Almost everybody would believe you…until Wittliff comes along and finds the beauty in that ugly place. He showed those women respect, and that showed their beauty. And dignity. It was there before he got there. He found it and preserved it.”

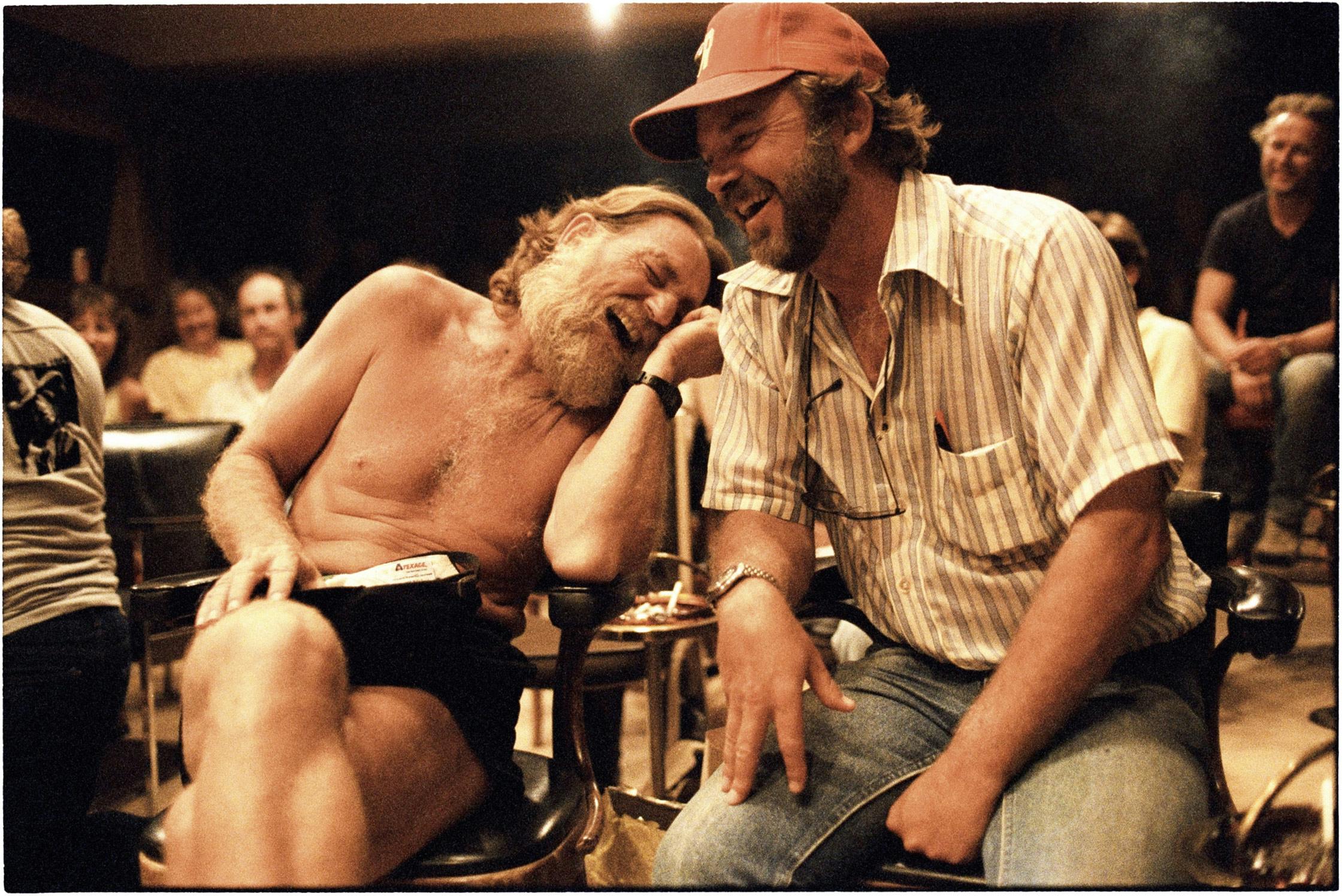

Screenwriting began as another sideline of the seventies. With no proper training, Wittliff worked up original scripts based on his small-town, Texas childhood with a hardworking single mother, a star turn for his buddy Willie Nelson, and a host of other stories. By the end of the decade his scripts were getting bought and produced and soon were on screens as Hollywood productions. Willie carried 1980’s Honeysuckle Rose. Sissy Spacek followed her Oscar-winning turn in the Loretta Lynn biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter by playing the simulacrum of Wittliff’s mom in 1981’s Raggedy Man.

But the script that brought the most acclaim was Lonesome Dove. Wittliff read McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning trail-driving saga when it was published in 1985, and a year later was hired to translate it to the screen. He had a friend read it onto tape, then listened to it on drives to the coast, picturing the action against the South Texas plains. Writing it took him a year.

“It wasn’t an adaptation,” said Jones, “It was a derivation, a condensation. You’ve got to let the book be your guide, and that’s not easy. It requires a confidence in your own creativity, along with a selflessness that not a lot of people have. Bill had it in abundance.”

But Wittliff was in no way a passive participant. His mantra on the set was “If we take care of Lonesome Dove, Lonesome Dove will take care of us,” and he worked tirelessly to protect the story. He had the final word, if not the original thought, on every prop, set, and costume design, on each actor’s accent and whether they looked right in a saddle. He made sure all their hats communicated something about their character but also stayed true to the time. He knew exactly how Lonesome Dove needed to look, feel, and sound.

“He was involved in absolutely everything,” said Jones. “He watched every foot of dailies. He was on the set 100 percent of the time. When I came up against some obstinate person with a stupid-ass Hollywood idea, I always had Bill to rely on. He’d say, “Don’t worry about it. I know it. We’ll get rid of it.” And he did.

Lonesome Dove aired over four nights in February 1989, earning blockbuster ratings and a staggering eighteen Emmy nominations. Though it was all but shut out from major awards on Emmy night—only the director, Simon Wincer, won a big one—Wittliff kept his chin up. As Duvall suggested, Lonesome Dove was on its way to worldwide adoration. And Wittliff was already at work on his true masterpiece.

The Wittliff Collections are essentially the sum of Wittliff’s parts. He started them in 1986, when he happened upon the archive of another old friend, Texas folklorist J. Frank Dobie. He wrote a check instantly, and explained why to Skip Hollandsworth for a 2001 Texas Monthly profile. “Sally and I wanted to create something we would call the Southwestern Writers Collection. It would be a place you could go to see artifacts of Texas writers who had struggled throughout their lives to find just the right word or the right phrase, who wanted to express a feeling, who needed to tell a story. I wanted a place that might inspire a new group of Texas writers.”

In the years since, the collections have grown to include photography, film, and music, expanding in a way only the Wittliffs could have dreamed. It houses manuscripts and personal papers of writers like Cormac McCarthy, Sandra Cisneros, and Sam Shepard, as well as the archives of Texas Monthly. It contains Billy Lee Brammer’s typed manuscript of The Gay Place and its unfinished sequel, plus the screenplay Larry McMurtry wrote and set aside in 1972, then later picked up and turned into Lonesome Dove, the novel. It’s got a 1555 edition of Cabeza de Vaca’s La Relacion, which contains the earliest known written description of Texas, Edward S. Curtis’s landmark photographs of Native Americans, and Mike Judge’s production files from King of the Hill. It’s got original lyrics Willie Nelson handwrote when he was eleven years old, four joints he once smoked to the roach-ends and left in the ashtray of Wittliff’s truck, Gus’s one-legged corpse that Call dragged back to Texas (or rather, the mini-series prop), and the paddle John Graves used on the canoe trip that became Goodbye to a River. Every one of those items is available for inspection to scholars, students, and fans, or anyone who happens in. They also all reflect, as should be obvious, the passions and friendships of Wittliff.

I asked Jones what he considered to be Wittliff’s great accomplishment. He jumped instantly to a terse response. “I’m not going to be the source of such an indignity as to sum him up in a sentence. No. His greatest accomplishment? Hell, I don’t know. He loved his grandchildren.”

That brought to mind my own favorite memory. My first interview with Wittliff for the Lonesome Dove research was a long, rambling conversation in his office. The building itself was a piece of living history, an old Victorian home just west of downtown. O. Henry once rented a room there, and Bill and Sally bought it in 1973 to house Encino Press. At Wittliff’s invite, Bud Shrake and Steve Harrigan wrote novels in a room upstairs, and the world’s most famous birdwatcher, Victor Emanuel, started his business there. The walls of the room where Wittliff actually worked were hung with fine prints of photos he’d taken of Graves, Willie, and Duvall and Jones as Gus and Call, and every inch of shelf and tabletop—and much of the floor—was stacked tall with books and manuscripts, some he was working on and others he was reading for friends. Amid all that, he mused for two hours on the brilliance of McMurtry, the mysteries of Texas, the lunacy of Hollywood, and his eternal belief in the power of a well-told story. It was a perfect afternoon.

But the real insight came before I’d gotten to the door. As I walked up, Reid Wittliff was leaving. He’s an attorney in Austin now, and he’d just had lunch with his dad. He stopped on the porch and they gave each other a long, strong hug.

I told all that to Jones. “Wittliff walked me through every memento,” I said. “He explained his great miniseries, the relationships that came out of it and how much it all meant to him. But I got a real sense that with everything we got into that day, to his mind, the most important thing was that hug with his son.”

Once again, Jones didn’t pause for even a beat. “The most beautiful thing I saw on that first fly-fishing trip,” he said, “was Bill make a bologna sandwich for Reid. It consisted of cheap white bread, mayonnaise, and bologna. Maybe a slice of American cheese. I never saw anyone take such care to make a bologna sandwich. And I have never forgotten it.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Tommy Lee Jones

- Bill Wittliff