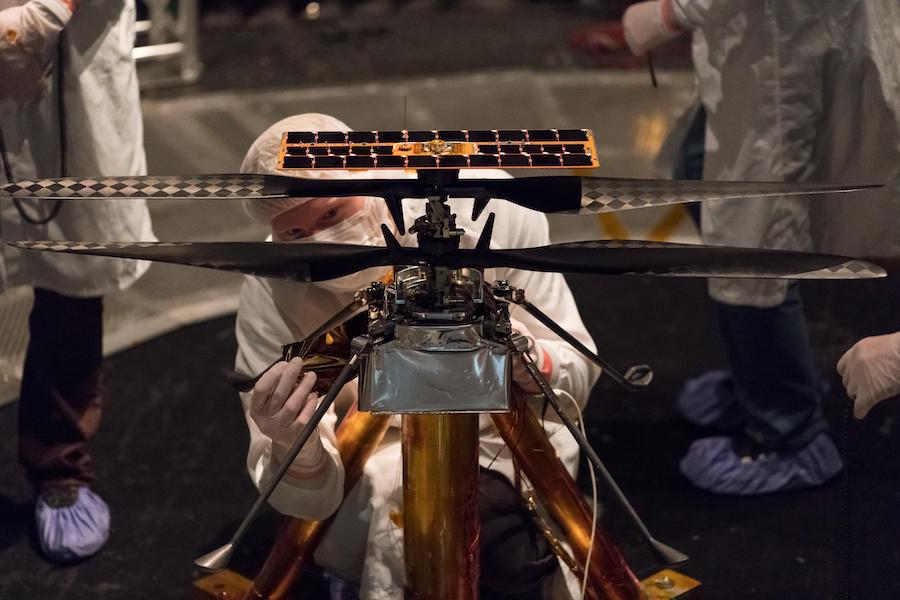

Engineers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California have attached a flying helicopter drone to the belly of the Mars 2020 rover set for launch next July.

The solar-powered Mars Helicopter stands about 2.6 feet (80 centimeters) tall when fully deployed, and will become the first aircraft to fly on another planet. The robot drone will ride to the Red Planet with NASA’s Mars 2020 rover, which has been assembled at JPL to begin testing in the coming weeks.

The Mars 2020 mission is scheduled for launch from Cape Canaveral on July 17, 2020, the first day of a nearly three-week window for the rover to depart Earth and head for Mars. The rover will blast off atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket.

The installation of the Mars Helicopter to the underside of the Mars 2020 rover Aug. 27 was one of the final tasks for the mission’s integration team at JPL. Engineers will put the craft through a series of preflight checks, beginning with a vibration test with the rover attached to its sky crane descent stage, the same type of landing vehicle that delivered the Curiosity rover to Mars in 2012.

“With this joining of two great spacecraft, I can say definitively that all the pieces are in place for a historic mission of exploration,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of the science mission directorate at NASA’s headquarters in Washington. “Together, Mars 2020 and the Mars Helicopter will help define the future of science and exploration of the Red Planet for decades to come.”

The Mars 2020 mission’s primary goals include searching for signs of ancient microbial life on Mars. The rover will collect rock samples for retrieval by a future mission to return the specimens to Earth, and test out a device to generate oxygen from the carbon dioxide in the Martian atmosphere.

NASA officials approved the addition of the helicopter to the Mars 2020 mission last year.

Fitted with a counter-rotating pair of blades, the mini-helicopter is a technology demonstration experiment. After the rover arrives at Mars on Feb. 18, 2021, it will drop the drone on the Martian surface and drive a safe distance away, continuing with its own scientific investigations independent of the helicopter.

A cover will shield the helicopter from debris during the rover’s entry, descent and landing at Mars.

“Our job is to prove that autonomous, controlled flight can be executed in the extremely thin Martian atmosphere,” said JPL’s MiMi Aung, the Mars Helicopter project manager at JPL. “Since our helicopter is designed as a flight test of experimental technology, it carries no science instruments. But if we prove powered flight on Mars can work, we look forward to the day when Mars helicopters can play an important role in future explorations of the Red Planet.”

The helicopter will fly autonomously, without real-time input from ground controllers millions of miles away. The drone carries two cameras, and telemetry from the helicopter will be routed through a base station on the rover.

The atmosphere at the Martian surface is about 1 percent the density of Earth’s, limiting the performance of a rotorcraft like the Mars Helicopter.

The rotors on the Mars Helicopter will spin between 2,400 and 2,900 rpm, about 10 times faster than a helicopter flying in Earth’s atmosphere. The altitude record for a helicopter on Earth is around 40,000 feet.

NASA says future Mars helicopters could carry scientific instruments and act as scouts for rovers, and eventually humans, exploring the Red Planet. Drones could survey cliffs, caves and deep craters, places where it might be too risky to send a crew or an expensive rover, NASA said in a statement.

Aerial imagery could also help locate obstacles for rovers as they drive across the Martian surface.

The Mars Helicopter demonstration is not the only flying robot NASA is developing to send to another world.

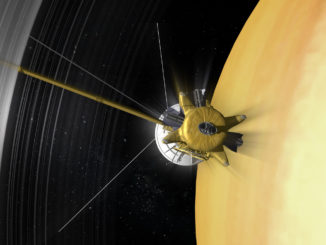

Earlier this year, NASA approved development of a mission named Dragonfly, which will use a rotorcraft to fly through the atmosphere of Saturn’s largest moon Titan.

Unlike the Mars Helicopter, Dragonfly is a full-fledged research mission with its own suite of scientific instruments. Titan is covered with a thicker atmosphere than Earth, making it a more favorable environment for a rotorcraft than Mars.

But Saturn is more than six times farther from the sun than Mars, so designers plan to rely on a nuclear generator to power Dragonfly around Titan.

Email the author.

Follow Stephen Clark on Twitter: @StephenClark1.