Andrew Yang had been the CEO of the boutique test prep company Manhattan Prep for about a year when the country began its plunge into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. He remembers feeling anxious and calling his bank to make sure that funds in the corporate account were still accessible. It soon became clear, though, that a deep recession was one of the best things that could’ve happened to Manhattan Prep.

In 2008, as Bear Stearns and Merrill Lynch collapsed, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 33.8 percent, and 2.6 million U.S. jobs disappeared, Manhattan Prep saw unprecedented success. Its enrollments surged by 50 percent year over year, and the company had to fly in tutors from North Carolina and Georgia to accommodate the interest. “As all of these young people lost their jobs, a lot of them turned toward business school,” Yang told Slate. “Lehman Brothers failed one day, and then literally the next day all of our New York classes were oversubscribed.”

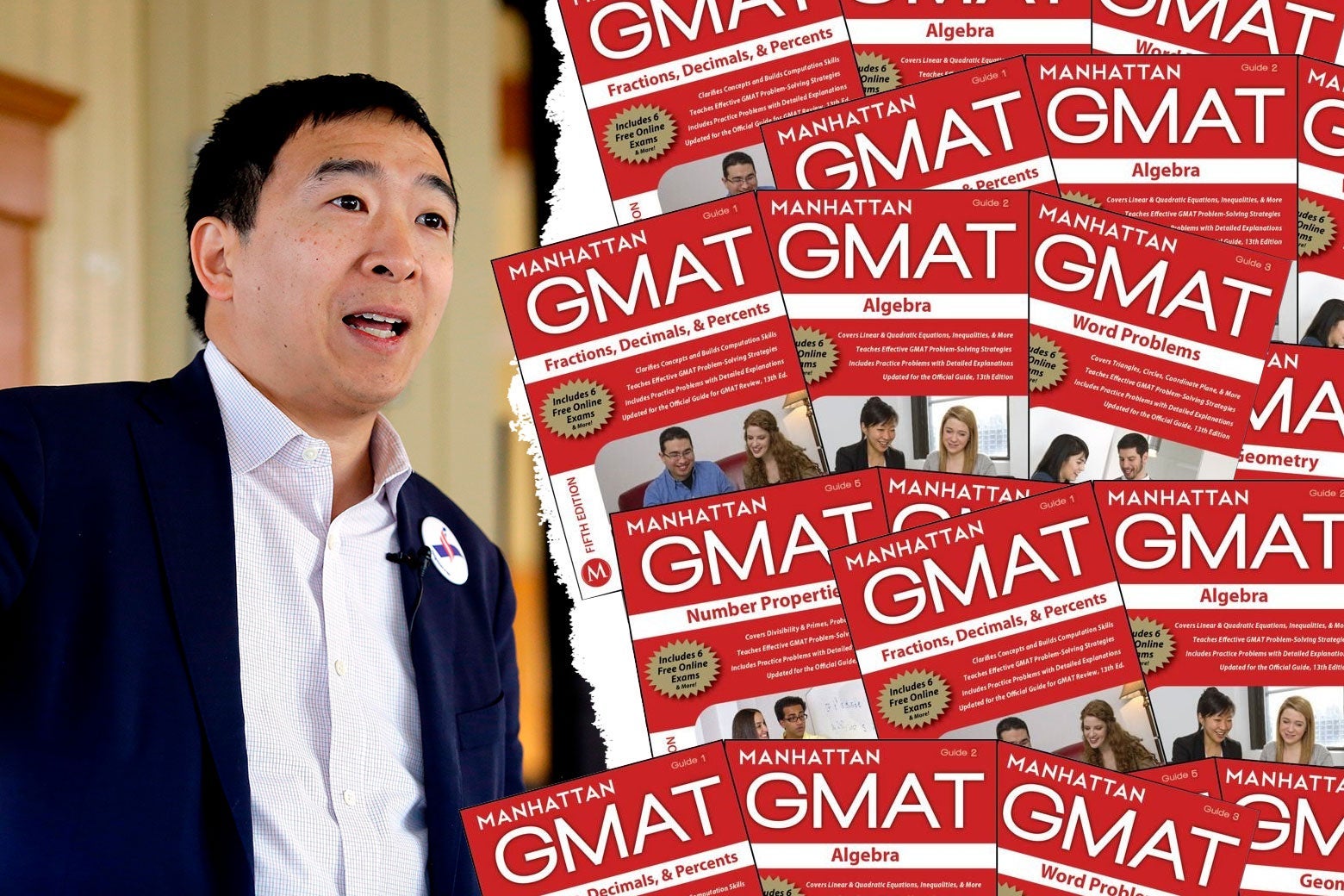

The company hired aggressively, expanded into new cities, and began selling an LSAT course in addition to its core offering for the GMAT, a standardized test taken by students applying to MBA programs. Yang was confident enough in the demand that he raised prices for the standard nine-week course by $100, to $1,490, in 2009. It was the company’s first price increase in more than two years. “I was continuously double-checking everything, because I was like, ‘Is this really too good to be true?’ ” he said.

Manhattan Prep grew to the point where it ranked first in the country for GMAT enrollments. Later in 2009, the testing giant Kaplan bought the company, and the deal earned Yang “some number in the millions.” (Disclosure: Kaplan and Slate are owned by the same parent company, Graham Holdings.) Yang wrote in his most recent book, The War on Normal People, that by 2010, he was “riding high.”

I was 35 years old, the head of a national education company that I loved, living in New York City among family and friends, and engaged to marry my fiancée the following year. I was on top of the world.

But Yang didn’t see his company’s success as evidence of visionary business prowess. “It’s not like we saw the financial crisis coming,” he said. “It’s not like one of these bullshit stories where we’re going to make something up—like [we were] building a business to benefit from a meltdown.” He had more or less stumbled upon this booming countercyclical industry and profited immensely.

A couple years after the Kaplan sale, Yang used a portion of his earnings to found Venture for America, a nonprofit dedicated to helping recent college grads establish startups in cities that were still trying to recover from the recession, like Cleveland and Detroit. The nonprofit acted as the stepping stone for his current insurgent presidential campaign, which features proposals for sweeping government policies to solve the problems he observed in those cities. The 2008 recession helped convince Yang that the American economy is dysfunctional—and made him wealthy enough to try to do something about it.

Financial crises shaped both the peaks and troughs of Yang’s early career. He made his first foray into entrepreneurship by leaving his job at a law firm in 2000 to co-found the startup Stargiving, a website that made small donations to celebrity charities each time a visitor clicked a button. The site would enter visitors into raffles to meet the likes of Magic Johnson and Hootie & the Blowfish. Websites such as Freerice eventually saw success using a similar web-based philanthropy model later in the decade, but Stargiving entered the market right when the dot-com bubble was beginning to burst and only survived for a couple years.

“Andrew actually was the first one to decide that this was not ultimately going to work out and decide to exit,” said Brian Yang (no relation), a former Stargiving employee and actor known for playing the part of forensics expert Charlie Fong on CBS’s Hawaii Five-0. “To this day—and Andrew and I joke about it—we think it’s still a great idea that was just at the wrong time.”

Yang worked at another startup that also capsized as the dot-com bubble burst and spent the next few years as a vice president at mobile and health care software companies in New York. He also began writing problem sets and tutoring part time for a company then called Manhattan GMAT. Zeke Vanderhoek, who founded Manhattan Prep in 2000, was roommates with one of Yang’s former high school classmates. Yang eventually joined full time and rose through the ranks in the company. In 2006, Vanderhoek left to start a charter school and appointed Yang as CEO.

Yang mostly kept the company running as it always had. “He didn’t make any waves when he came in,” Vanderhoek said. Manhattan Prep’s signature practice was to pay tutors $100 an hour, three or four times the prevailing market rate, in order to attract the cream of the crop. (In their pursuits after Manhattan Prep, Vanderhoek and Yang have both stuck to the principle that high wages lead to better quality of teaching. Vanderhoek’s charter school somewhat controversially pays its teachers $125,000, and Yang’s platform includes the proposal to “increase teacher salaries” across the board.)

Manhattan Prep coupled high salaries with exceedingly rigorous and selective hiring. The company would only hire tutors who had scored in the 99th percentile on the GMAT—and even among those who did, it only made a job offer to 1 out of every 10 who applied. Top executives were intimately involved with the recruiting process, holding multiple rounds of interviews and serving as students in the audition lessons. Yang always played the “too-smart” student. “He had this very complicated solution, and you had to see if you could follow him and find the error in it,” Noah Teitelbaum, now vice president of instruction at the company, said of his own interview. “I remember not being able to follow it at all.”

Yang was blunt with applicants, telling them what they needed to improve and pointing out typos in their résumés. Teitelbaum recalls that he once brought a promising applicant to a meeting with Yang for a final check before making a job offer. When the applicant sat down, Yang abruptly said, “Too much cologne.” He ultimately signed off on the hire.

After joining the company, though, Yang’s former employees say they found a chill startup vibe, and a boss with a whimsical presence in the office. Yang constantly sang musical narrations of what he was doing, like sending emails, and would strike a gong on Friday evenings to tell everyone to go home. Nearly every day he wore a blazer and a dress shirt without a tie, similar to the outfit he’s donned on the campaign trail. (Employees had plans to show up to work all dressed in Yang’s standard outfit, though it never came together.) Yang once organized a company outing to see Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark, a Broadway musical that had received strongly negative reviews. Teitelbaum recalls Yang saying, “Let’s go! It’s so terrible it’s great!”

Manhattan Prep employees claim that Yang was unfazed when the news of major bankruptcies and market failures hit in 2008. “If he was worried, he hid it very well,” said Ronit Reinhard, an executive director at the company.

The boost in enrollments brought on by the turmoil was immediately clear. “Having that kind of an issue with the economy, while unfortunate for a lot of individuals, was good for businesses like test prep,” said Sam Edla, the director of IT. “Those were some pretty heady days … really, really skyrocketing numbers.” A Washington Post piece titled “Seeking Shelter in Business Schools” reported at the time that registrations for the GMAT had risen nearly 30 percent compared with a similar period in 2005.

Yang and the seven employees who spoke to Slate for this story contend that, while the recession may have been an odd and unexpected stroke of good luck, the company was well-positioned to take advantage of the windfall. For one, it was headquartered in New York City, the epicenter of the financial meltdown, and had developed partnerships with Wall Street firms. Although some of the partnerships fell through because of the strained economic environment, people who were losing their jobs at those firms knew from word of mouth that Manhattan Prep had exacting standards for its staff. Tutors began holding sessions during the day, instead of just in the evenings, given that many of these newly jobless test takers no longer had to be in an office from 9 to 5.

There was also an influx of résumés. The $100-per-hour salary lured business grads who were suddenly out of work, and this enlarged pool of qualified applicants provided the staffing necessary for the company to set up shop in cities like Houston and Seattle. During the interview process, company executives had applicants teach them a lesson on a topic of their choice. Chris Ryan, a vice president at Manhattan Prep, began noticing in 2008 that there were more and more people who chose to teach lessons on collateralized debt obligations, the same financial products that were bringing the economy to its knees. “The company grew a lot because there were people applying who might not have considered [doing test prep],” Ryan said. “No one grows up saying, ‘I’ll do test prep.’ ”

Yang certainly didn’t have long-standing ambitions to be a test prep tycoon. In fact, he has mixed feelings about standardized testing, believing it enables the myth of meritocracy. “Most of success today is about how good you are at certain tests and what kind of family background you have,” Yang writes in The War on Normal People. He adds, later, “Intellect as narrowly defined by academics and test scores is now the proxy for human worth.” Yang, who in his book attributes much of his success in life to the fact that he “was very good at filling out bubbles on standardized tests,” now thinks that society needs to deemphasize testing. He told Slate, “The fact that so many kids have their ambition shaped by their performance on these tests is unfortunate.”

During the tail end of Yang’s time at Manhattan Prep, he decided that he would use some of his newfound wealth to launch Venture for America. “I definitely had, like, a soul-searching period and came up with the idea during this time, which you could very directly see as a response to what I saw as the CEO of Manhattan Prep and the financial crisis,” he said.

Given the outsize role that recessions have played in his life, it’s perhaps no surprise that Yang is now running on a platform predicated on extreme skepticism of the markets. “It’s up to us; the market will not help us,” he wrote in his latest book. “Indeed, it is about to turn on us.” Yang’s doomsday predictions for a country torn apart by market-driven automation, inequality, and job loss have earned him a reputation as the “chaos candidate” and “the candidate for the end of the world.” As he told the Verge, “Relying on the market is going to get more and more destructive as it zeroes out more and more people.” Yang, a man whose fortunes have been so closely and unpredictably tied to financial crises, talks about the economy as if it were the mercurial God of the Old Testament: just as likely to give as to take away.

“When things bubble, everyone’s going to think they’re a genius, and then when they burst, everyone changes their tune very dramatically. I went through that in 2001, went through that in 2008, 2009. We’re overdue to go through it again,” he said. “People will forget what it’s like. It’s funny how short people’s memories are.”