“We just had to hop the fence. It was kind of easy,” says Ghost, co-founder of HK Urbex, as he explains how the urban explorer group gained access to the former mansion of late martial arts superstar Bruce Lee.

Wearing masks to protect their identities, the group circled the abandoned home in Hong Kong’s upscale Kowloon Tong neighbourhood three times to make sure the coast was clear. As one member stood out front to keep watch, another leapt over the back fence. Twenty minutes later they were out again – another successful urban mission accomplished.

This sounds familiar from reports of urban explorers operating in cities around the world, but the eight-strong Hong Kong group are quick to distance themselves from people who illegally access rooftops just to take selfies and post them on social media.

Once inside Bruce Lee’s former mansion, HK Urbex took photos and video of the interiors and exteriors to add to the list of more than 100 derelict and demolition-threatened sites they have documented since Ghost and Echo Delta formed the group in 2013.

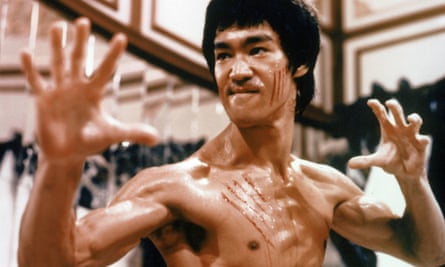

Bruce Lee and pictures of his former home

With backgrounds in journalism, videography and photography, the group say their aim is to preserve the memory of the city’s fading heritage before these buildings are lost forever.

“We wish we had the money to buy sites and preserve them as they are, but we don’t,” says Ghost, who does not reveal his real name. “So we do what we can to document them and try to preserve their memory. These places are part of our culture, part of our history … they shouldn’t just be wiped away.”

The group sees the state of Lee’s former home, where the actor lived with his family until his death in 1973 aged 32, as a particular failure of the city authorities.

“Bruce Lee’s home touched us a lot,” says Ghost. “Hong Kong has never done anything proper to honour his legacy. They had the chance to rebuild his former home into a museum, but instead it became a seedy love hotel.”

A former multi-storey dye works on the Sai Kung peninsula that became studios for ATV, best known for the Hong Kong version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?

The love hotel has long been closed. In November, the charitable trust that owns the property announced that the derelict mansion would be renovated and turned into a centre for Chinese studies.

“It’s a shame,” adds Ghost, “because Bruce Lee was called ‘the son of Hong Kong’. He put the city on the map and paved the way for Jackie Chan and all these other superstars, and yet there’s no real lasting place in the city which memorialises him. It’s a missed opportunity.”

In Hong Kong – well known for its shortage of land and expensive property market – the list of heritage buildings that have met undesirable endings grows ever longer. Old buildings are frequently torn down to make way for newer ones, and making profits and keeping developers happy is widely viewed as a priority over heritage preservation.

Shaw Studios, which popularised the kung-fu film and was beloved by director Quentin Tarantino. ‘For a year, I’d watch one old Shaw Brothers movie a day – if not three,’ he told the Los Angeles Daily News in 2003

The Hong Kong government’s Antiquities and Monuments Office has to date granted 120 buildings and cultural landmarks permanent protection from development and has assigned grades to a further 1,444 historic buildings. However, the grading system does not prevent buildings from being demolished.

“Hong Kong’s pretty much always at the whim of powerful real estate companies – they pretty much control Hong Kong,” says Echo Delta. “The government might, through the antiquities board, give recommendations to preserve certain sites but it’s kind of toothless. They just give a recommendation and there’s no actual power to stop it from being demolished.”

In recent years, the group have witnessed some of their favourite heritage sites fall to the wrecking ball, or be redeveloped beyond recognition.

Central Market, built in 1939

Shaw Studios – once the world’s largest private studios and the heart of Hong Kong’s film industry – was demolished to make way for hotels and low-rise residential buildings.

Central Market – a 1930s Bauhaus-style heritage building in the centre – was abandoned for more than a decade before permission was given to redevelop the site, estimated to be worth £1.3bn. A new cultural and retail centre will be built there, although key elements of the original structure will be preserved.

Grade I-listed Nam Koo Terrace, a colonial-era mansion that is supposedly one of Hong Kong’s most haunted buildings

The group are concerned about the General Post Office. Built in 1976, it faces demolition to make way for new offices.

Another building under threat is Nam Koo Terrace, a century-old mansion in the Wan Chai area. The group entered and documented the mansion – dubbed Hong Kong’s most haunted building – last year after reports it might soon be redeveloped. “The mansion is adjacent to a wooded hill that developers have just steamrolled over,” says Echo Delta. “We went to document it while we could.”

Although trespass is illegal, they have so far avoided any serious run-ins. “We try to be very careful,” says Ghost. “Sometimes we plan for a month in advance before we go.” The one time a group member did get caught at an abandoned psychiatric hospital, the security guard who confronted him was friendly. “He just escorted us off the property while talking about the place,” says Echo Delta.

The State theatre, now saved from demolition. Fittingly, it makes an appearance in Bruce Lee’s final film, Game of Death

The group have more than 20,000 followers on Facebook, and often receive requests from students and professors asking to use their work in academic studies of threatened or demolished sites. Last year, pictures HK Urbex took of the under-threat State theatre helped a local heritage group successfully campaign for it to be designated a Grade I historic building, which ultimately prevented its demolition. The majority owner of the property has now agreed to retain the theatre even if it does develop new residential and commercial parts of the site.

“This was the only good news out of 2018 for us,” says Ghost. “At the speed at which Hong Kong is developing, it’s becoming more of a race against time for us.

“We just hope that as more and more people become aware or concerned with heritage preservation that they will disseminate the knowledge that there’s all this heritage in Hong Kong that ought to be preserved. It’s part of our collective memory and once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, catch up on our best stories or sign up for our weekly newsletter