A Big Seattle Reading List

Jump to a Genre:

Nonfiction / Fiction / Memoir / Poetry

Nonfiction

American Romances by Rebecca Brown (2009)

Reading this book of essays by Rebecca Brown is like going on a road trip through American culture with someone who insists she knows where she’s going, GPS be damned. Nathaniel Hawthorne, Brian Wilson, Herman Melville, and Gertrude Stein get picked up along the way, and the resulting conversations are so lively that you stop worrying where you’re going; you just trust that Brown will get you there. –Ryan Boudinot

Before Seattle Rocked by Kurt E. Armbruster (2011)

If you’re to read only one book on Seattle music, let it be this. Most of us know about this city’s guitar rock bona fides. Far less known about is the region’s other music—from Native traditions to jazz to folk to symphonic brilliance. Kurt E. Armbruster’s account is swift, witty, and comprehensive.

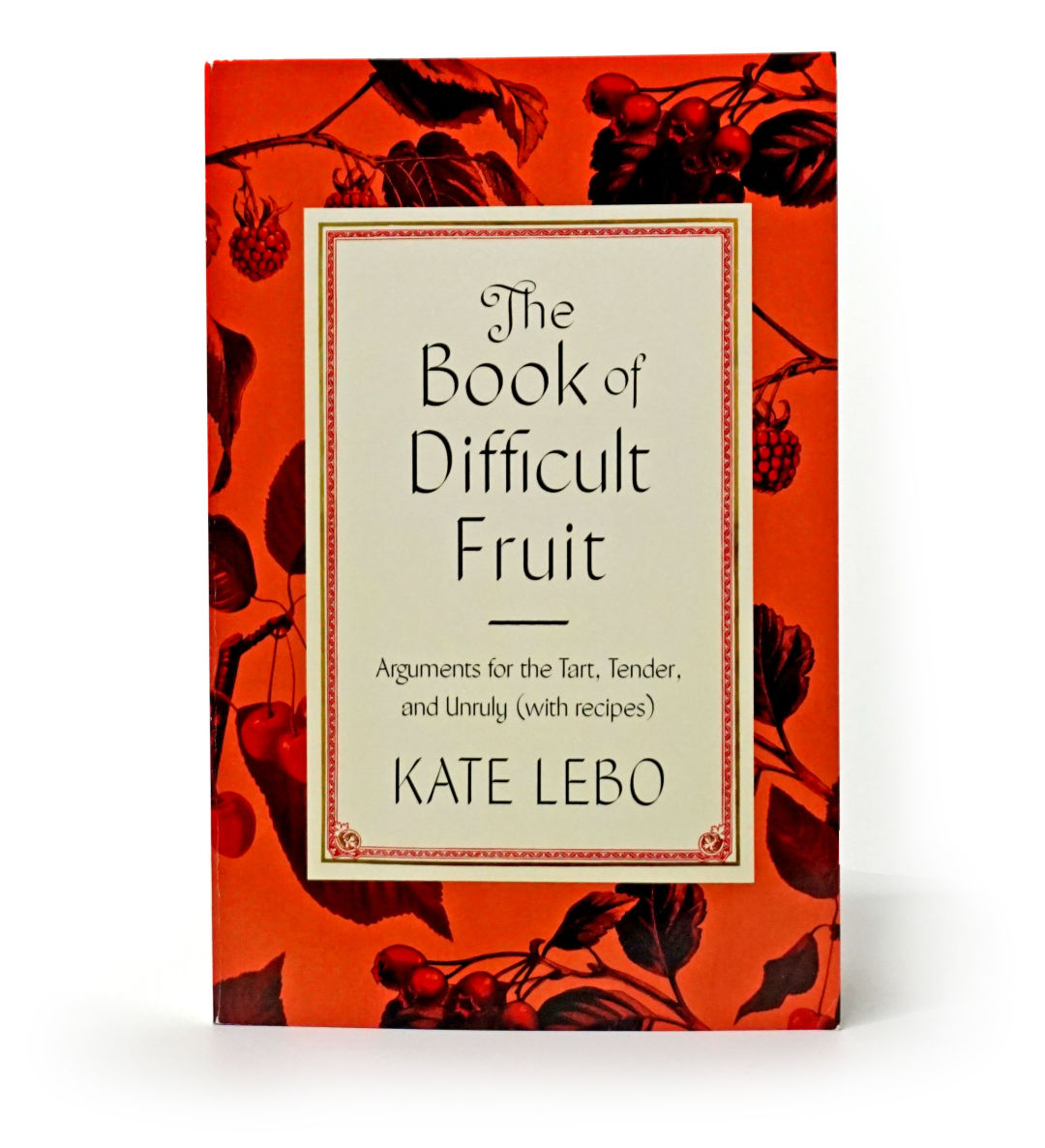

The Book of Difficult Fruit by Kate Lebo (2021)

“In this book, fruit is not the smooth-skinned, bright-hued, waxed and edible ovary of the grocery store,” Spokane’s Kate Lebo writes at the start her new essay collection. Here, fruit is a pain—but, as pains go, a pretty good one. The book that follows is a compendium, an alphabetical rundown of 26 mostly counterintuitive fruits, from aronia to zucchini (for W we get wheat instead of watermelon). Each fruit is also the occasion for a lyric essay and recipe. So after Lebo has described aronia berries (“taste vegetal, like a grass stem, then sour, like a crabapple”), we get a passage on what Lebo thinks daily aronia berry smoothies might do for her: “I would believe they are three to four times healthier than blues even if their packaging didn’t say so, because they immediately assert their potency.” Then she gives you the recipe for said smoothie.

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown (2013)

Snagging comparisons to Unbroken, Daniel James Brown’s nonfiction saga tells the unlikely story of the University of Washington men’s row team, which competed in the 1936 Berlin Olympics and beat out Hitler’s German rowing crew. The Boys in the Boat is a triumph of sports history and of storytelling from a local author.

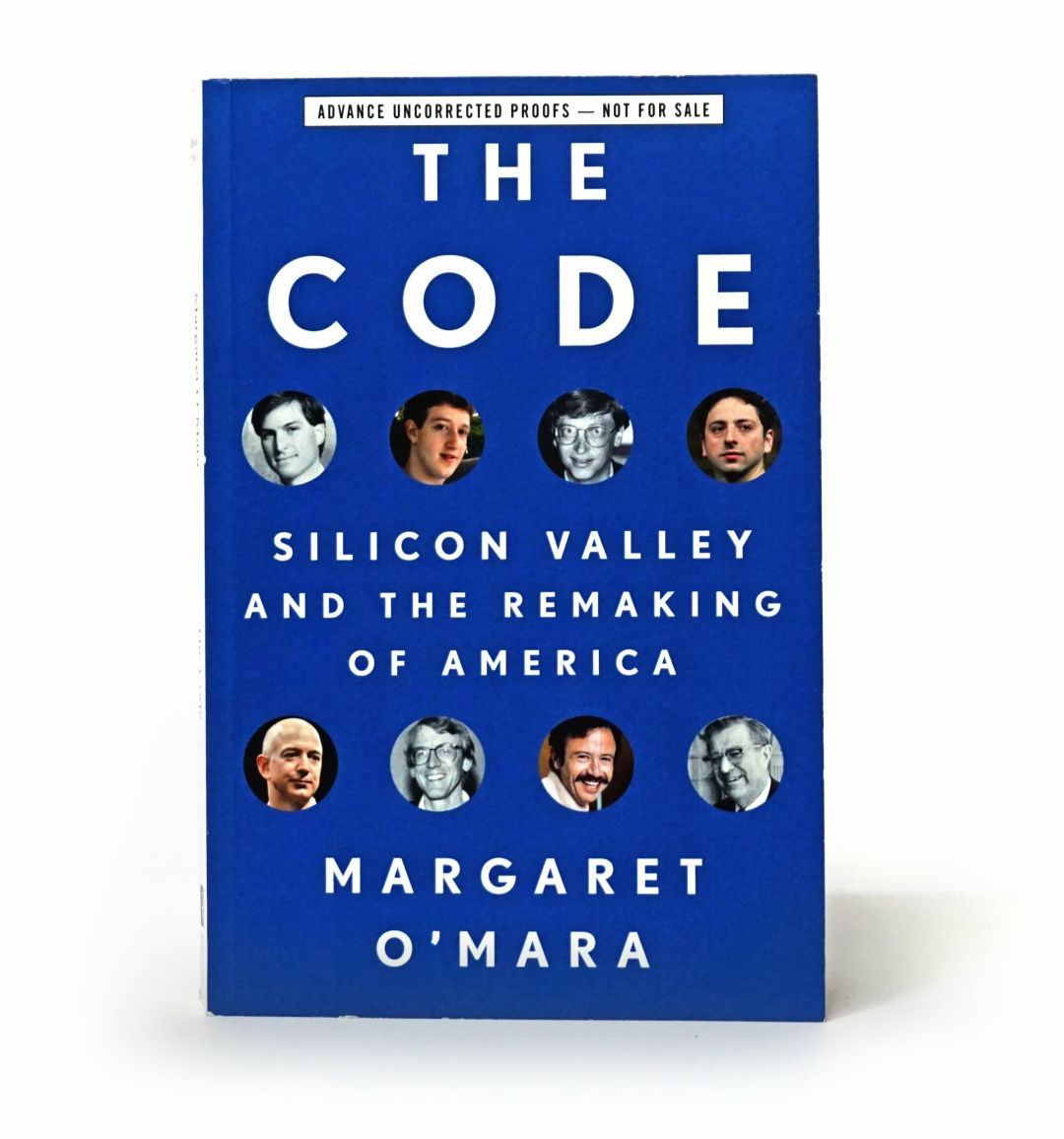

The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America by Margaret O’Mara (2019)

Starting in 1949 Palo Alto and ending in 2018 San Diego, The Code, by University of Washington history professor Margaret O’Mara, is not merely an investigation of Seattle’s southerly “sister technopolis” (her phrase). O’Mara’s focus here is on the part of the story that is often overrun in the nebbish Wild West narrative, in which a few brilliant kids bootstrapped empires into existence. Instead, she writes, “the Valley’s tale is one of entrepreneurship and government, new and old economies, far-thinking engineers and the many non-technical thousands who made their innovation possible.”

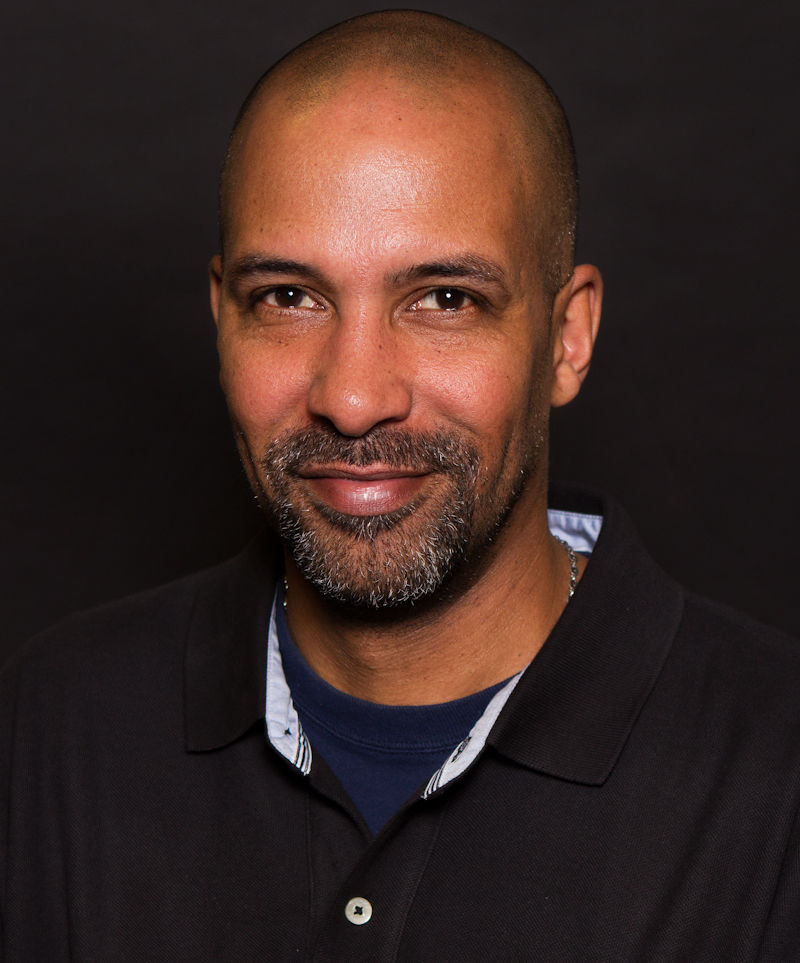

Daubi Abe.

Image: Courtesy UW Press

Emerald Street: A History of Hip Hop in Seattle by Daudi Abe (2020)

As Daudi Abe notes in this book, for much of the genre’s four-decade history, the public at large has mostly not seen Seattle as a hip-hop town. So Abe’s work—which traces a local scene’s history from the Emerald Street Boys in the 1980s to the present—is well worth a read if you’re interested in Seattle music and history. It’s written in a plain academic register, but as he dips into various facets of the scene through the decades, Seattle hip-hop’s identity emerges—intelligent, idiosyncratic, progressive, diverse in population and sound, often needlessly self-effacing. Full review here.

Gay Seattle by Gary Atkins (2003)

This century-long account of Seattle’s gay community begins in 1893 as laws set out to criminalize queerness. Over its more than 460 pages, you fly through the city’s early burlesque and drag scenes, the AIDS crisis, and how Capitol Hill became a gay neighborhood. Pretty much anyone can learn something here, but it’s especially good reading for newer Seattleites, so they can put history to some touchstone names, like Seattle actress Frances Farmer (not just a Nirvana song!) and Washington’s first openly gay state legislator, Cal Anderson (not just a park!).

Girls to the Front by Sara Marcus (2010)

Why’d it take until 2010 to get a narrative account of riot grrrl? Okay, Sara Marcus is not local. But her book is a smart, high energy retelling of feminist punk scenes that sprouted in the two Washington capitals (DC and Olympia) and it connects local music to national.

Heavier Than Heaven by Charles Cross (2001)

Kurt Cobain’s legacy is Charles Cross’s domain. Cross wrote for the seminal Seattle music magazine The Rocket, which kids from all over the Pacific Northwest depended upon for news of the grunge revolution. That scrappy rag chronicled a once-in-a-lifetime musical renaissance, the pinnacle of which was Nirvana. In this biography and a number of other books (Here We Are Now: The Lasting Impact of Kurt Cobain is a more reflective follow-up), Cross approaches his subject with honesty and sensitivity. Heavier Than Heaven, like the best Nirvana songs, delivers sorrow and inspiration in equal measure. See also Cross’s Jimi Hendrix biography, Room Full of Mirrors. –RB

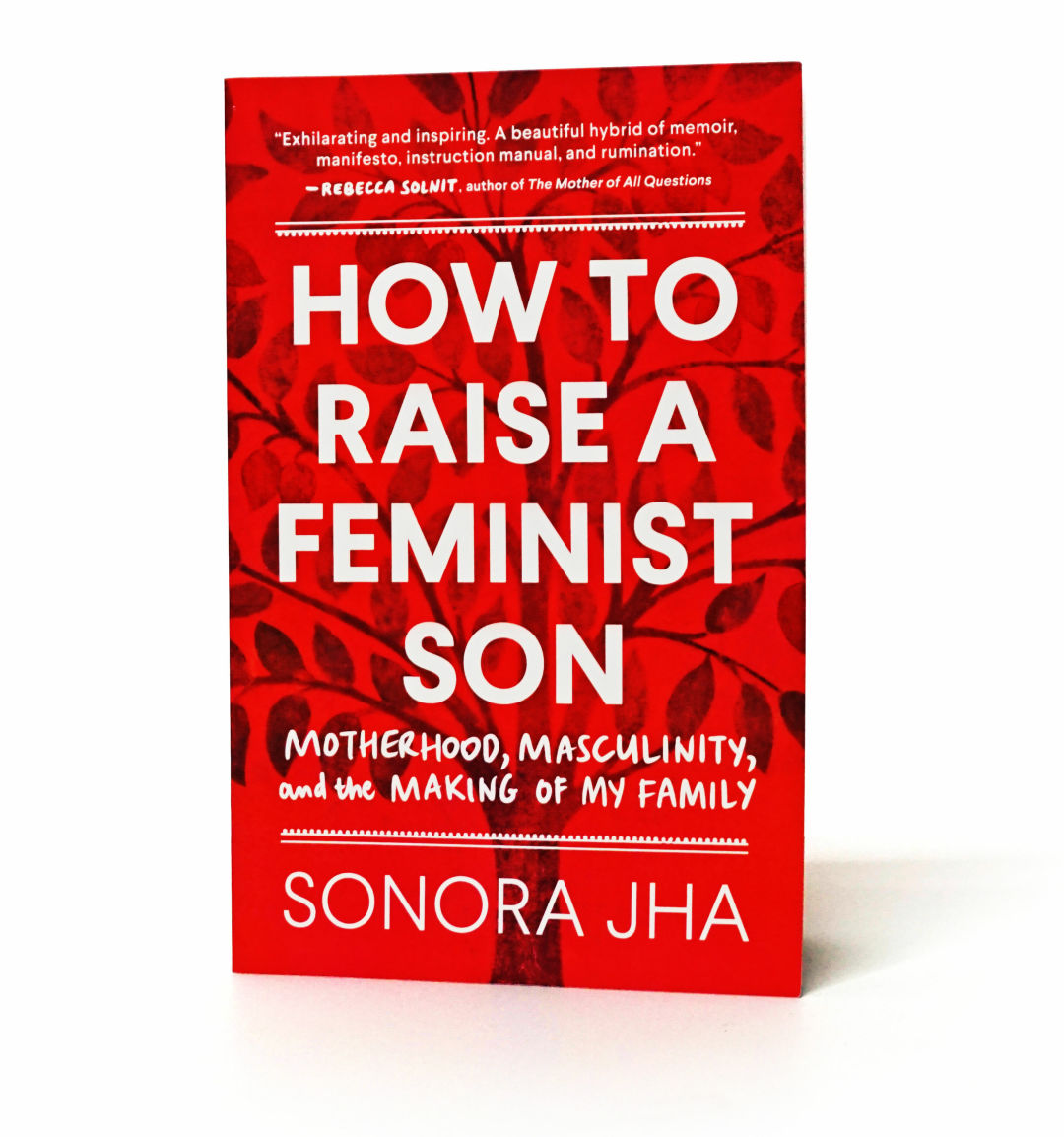

How to Raise a Feminist Son by Sonora Jha (2021)

Part guide, part memoir, Sonora Jha’s book is for anyone trying to raise feminist boy in a world that’s generally designed to produce the opposite. In each chapter, Jha, a Seattle University professor, sets out to tackle a question (“What If I’m Not a Good Feminist?” and “Do I Really Have to Talk to Him about Sex?”) and includes to-do bullet points at the end. But much of the text also concerns Jha’s own journey—as a writer and a mother—from her time as a reporter in India to how she’s used movies as a teaching tool (Bechdel-Wallace test, male gaze) with her now-grown son.

Into the Wild by Jon Krakauer (1996)

If you pat yourself on the back for being adventurous because you occasionally throw a tent in the back of your Prius and head to the Olympic Peninsula for the weekend, reading Into the Wild will disabuse you of the notion. The tragedy of Christopher McCandless, an idealistic young man who rejected civilization to live alone in the wilderness of Alaska, was adapted into a movie directed by Sean Penn, but the book goes far deeper into its ill-fated protagonist’s motivations. The rigor of research by former Seattleite Krakauer works in harmony with his empathetic take on his subject’s deeply held, but arguably misguided, beliefs. –RB

Jackson Street After Hours by Paul de Barros (1993)

The phrase definitive account gets trotted out an awful lot to describe history books. But, for Paul de Barros’s look at Seattle’s incredible jazz scene, which peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, such language is unavoidable. It’s evocative and richly researched—including interviews with the marquee names that helped form the scene: Ernestine Anderson, Quincy Jones, Ray Charles. The compendium of photographs alone is worth a look.

Like a Mother by Angela Garbes (2018)

Did you know the placenta is an organ? (It is, and it plays a fascinating, if finite, role in pregnancy.) Did you know that breast milk is made from a mother’s melted-down body fat? (Yup, from the butt and thigh). In her book, Angela Garbes approaches all things pregnancy with the skepticism of a journalist (she is one) and the grace of a humorist, all while staying true to the science mothers-to-be seek. –Sam Luikens

Angela Garbes with her children.

Image: Carlton Canary

Native Seattle by Coll Thrush (2007)

The first clue that Coll Thrush’s 2007 book does important work is in the subtitle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. This nation and city love to treat Indigenous peoples as a singularity, a continuous culture running coast to coast, which is unconscionably stupid. Thrush’s book delves into the varied generations, who have called and still do call this land home. It’s important work anywhere, yet as Thrush writes, “Every American city is built on Indian land, but few advertise it like Seattle.”

Protest on Trial: The Seattle 7 Conspiracy by Kit Bakke (2018)

In 1970, members of the Seattle Liberation Front, a young leftist group, gathered dissidently outside the federal building downtown, hurling rocks and paint bombs. A few months later, a grand jury had seven of them arrested on conspiracy and riot charges. The trial became a media riot itself, with the group known as the Seattle Seven (including Jeff Dowd, inspiration for the Dude in The Big Lebowski) mocking the establishment they were protesting in the first place. Author Kit Bakke, a Seattleite and once active in the radical organization the Weathermen, works from interviews and documents to turn this story into a courtroom drama and, occasionally, a farce.

Lyanda Lynn Haupt.

Rooted: Life at the Crossroads of Science, Nature, and Spirit by Lyanda Lynn Haupt

Seattle’s premier avian scribe follows Mozart’s Starling with this look into how the “innate connection between humans and the natural world is coming to the fore in a new way as academic research rises in support of truths” that are age-old. With an erudite and roving wit, Haupt writes about how trees can communicate with each other, and how we can connect with them simply by walking in the woods. And, of course, there are still birds.

Seattle Prohibition by Brad Holden (2019)

Probably you’ve heard of Roy Olmstead, Seattle’s “good bootlegger.” Maybe you know how intertwined Seattle jazz was with prohibition. Probably you know little else about this city’s prohibition history. While rummaging through a local basement, historian Brad Holden found a moonshine still, then documents saying the still’s owner had gone to jail. He turned this curiosity into a book, pulling up stories on people like Johnny Schnarr and Frank Gatt, the state’s major moonshine slinger.

Seattle in Black and White by Joan Singler, Jean C. Durning, Bettylou Valentine, and Martha J. Adams (2011)

Seattle’s Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) formed in 1961 and successfully took on discriminatory hiring practices at local grocery stores. The group even coordinated a “shop-in” where activists filled carts and asked cashiers if the store hired Black people. If not, the protestors walked out, jamming the lines. Other campaigns worked for more employment and housing for Black Seattleites. This book, written by four CORE members, recounts the group’s history.

Shrill by Lindy West (2016)

Former Stranger writer Lindy West’s essay collection is—much like its subtitle, Notes from a Loud Woman—an outspoken, brazenly feminist, and funny examination of fat shaming, internet trolling, and coming of age. But don’t let the volume level distract: West is adroit as hell, constantly dispatching wise and nuanced turns of thought and phrase.

► See also West's The Witches Are Coming.

Skid Road by Murray Morgan (1951)

This book’s title may be responsible for one of the worst hair metal bands of the 1980s, but don’t hold that against Murray Morgan. The story of our fair (read: muddy) city’s founding, Skid Road chronicles the optimism, greed, speculation, xenophobia, and venereal disease that put this supply point for Yukon prospectors on the map. The personalities enshrined in street names loom large—Yesler, Denny, Boren, and Mercer all get their moment in the spotlight—but it’s the hard-edged tales of vigilante justice, inebriation, and cathouse conflagrations that earn the book’s reputation as a page-turner. Under the sordid details you can detect the beginnings of what would become the progressive city we know today, most poignantly in the friendship between the drunk, polyamorous visionary Doc Maynard and the chief who gave Seattle its name. –RB

So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo (2018)

This primer on navigating race was published in 2018, a little over a year after many Americans could no longer ignore the fact that this country is deeply, systemically racist. As the title dictates, Ijeoma Oluo’s explanation is charismatically conversational, breaking down more academic language like “intersectionality” so that anyone can be included in the discussion. It helps that she’s funny and perceptive. One of her examples of cultural appropriation? The Africa Lounge at Sea-Tac, where you can order nachos from a zebra-print stool.

► See also Oluo’s Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America

Ijeoma Oluo.

Image: Justin Gollmer

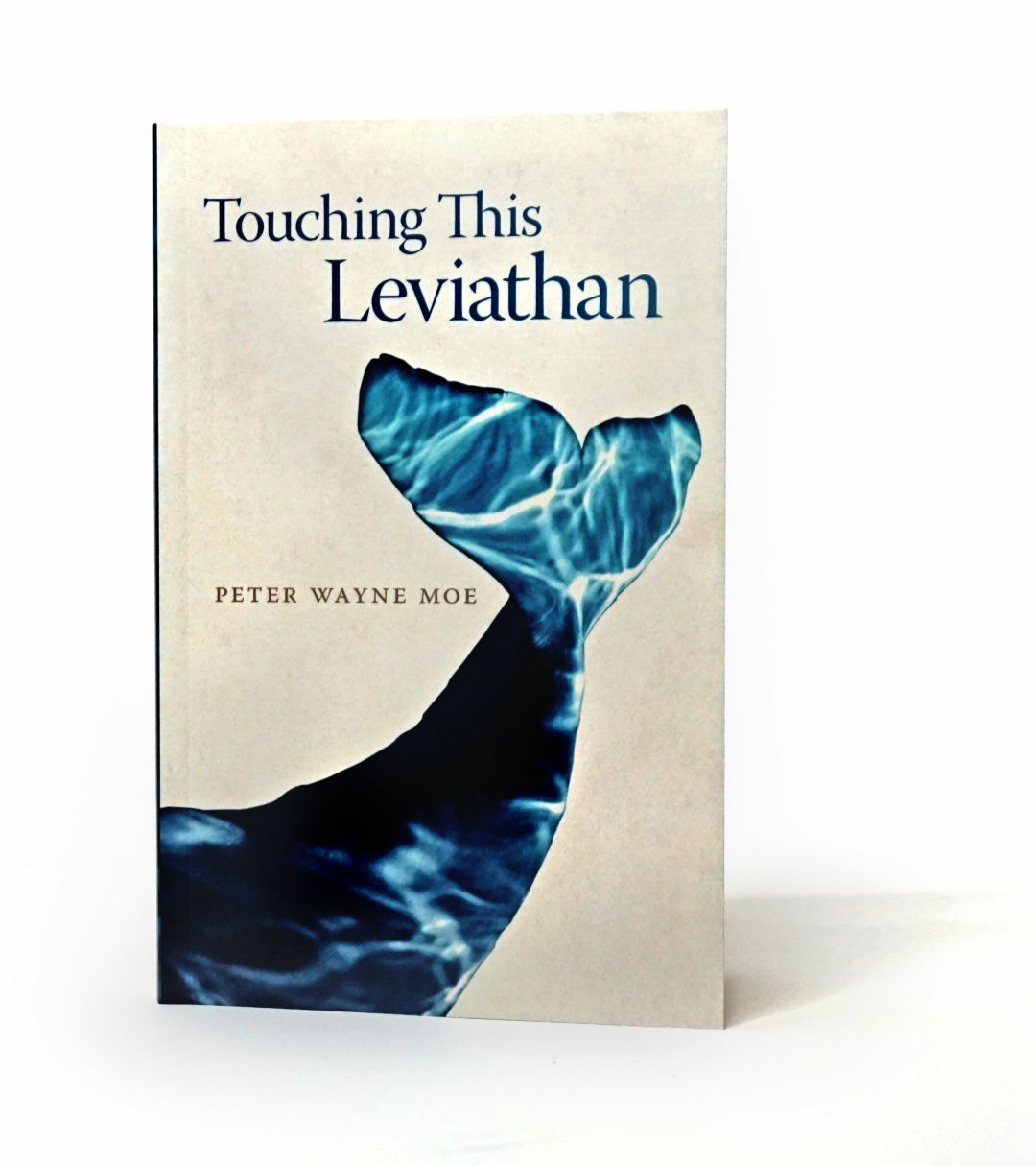

Touching This Leviathan by Peter Wayne Moe (2021)

“To cook the thing up,” wrote Herman Melville of Moby Dick, “one must needs throw in a little fancy, which from the nature of the thing, must be as ungainly as the gambols of the whales.” As a sort of rejoinder, Peter Wayne Moe’s new book about whales, Touching This Leviathan, is thoroughly gainly, a lean 126 pages. It does, however, “throw in a little fancy.” Moe, a Seattle Pacific University professor, weaves personal essay (whale watching in the Northwest, memorizing The Book of Jonah), biology, theology, history, criticism, and more than a few Melville references into a book that “asks how we might come to know the unknowable.”

White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo (2018)

In 2011, sociologist (and University of Washington professor) Robin DiAngelo coined the term “white fragility” to refer to the unwillingness of white people to engage in the uncomfortable and painful conversations about race. This book expounds on the term, with DiAngelo, a white progressive, asserting that “white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of color." Since its publication, the book’s value has been hotly debated—with some critics arguing that it condescends to Black people and simplifies people of color, that it merely papers over the real problems of whiteness with a new rhetoric. Certainly, though, it’s gotten people talking.

The Worst Hard Time by Timothy Egan (2006)

A longtime correspondent for The New York Times, local Timothy Egan has often written books on topics revolving around the West and conservation: the photographer Edward Curtis, the Great Fire of 1910, his own journey through the Northwest. This book is no exception, plunging into stories from the Great American Dust Bowl (it nabbed him a National Book Award). Told as a disaster narrative, the book follows farmers as the land they’d plowed rises up and is hurled back at them in a 50-mile-per-hour crucible of soil. It also steps back to look at the government’s culpability in creating such conditions and the lasting damage on the High Plains.

Fiction

The Bachelor by Andrew Palmer (2021)

This novel’s narrator, a writer and bachelor, is indeed fixated on the reality TV show The Bachelor. After a failed sort-of engagement, he leaves the East Coast to house sit in Des Moines, Iowa. Ultimately, he’s attracted to the stories of others. Along with The Bachelor, he develops an obsession with the life and work of poet John Berryman, who led a raucously unhappy life, drifting between drink and women. In a way that brings to mind Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist, much of Palmer’s novel is given over to explications of both these topics (and several others) in agile, genially ironic writing. In a playful meta-commentary, this bachelor’s begins to mirror both the Bachelor’s and Berryman’s as he develops relationships (platonic and not) with the women around him. Full review here.

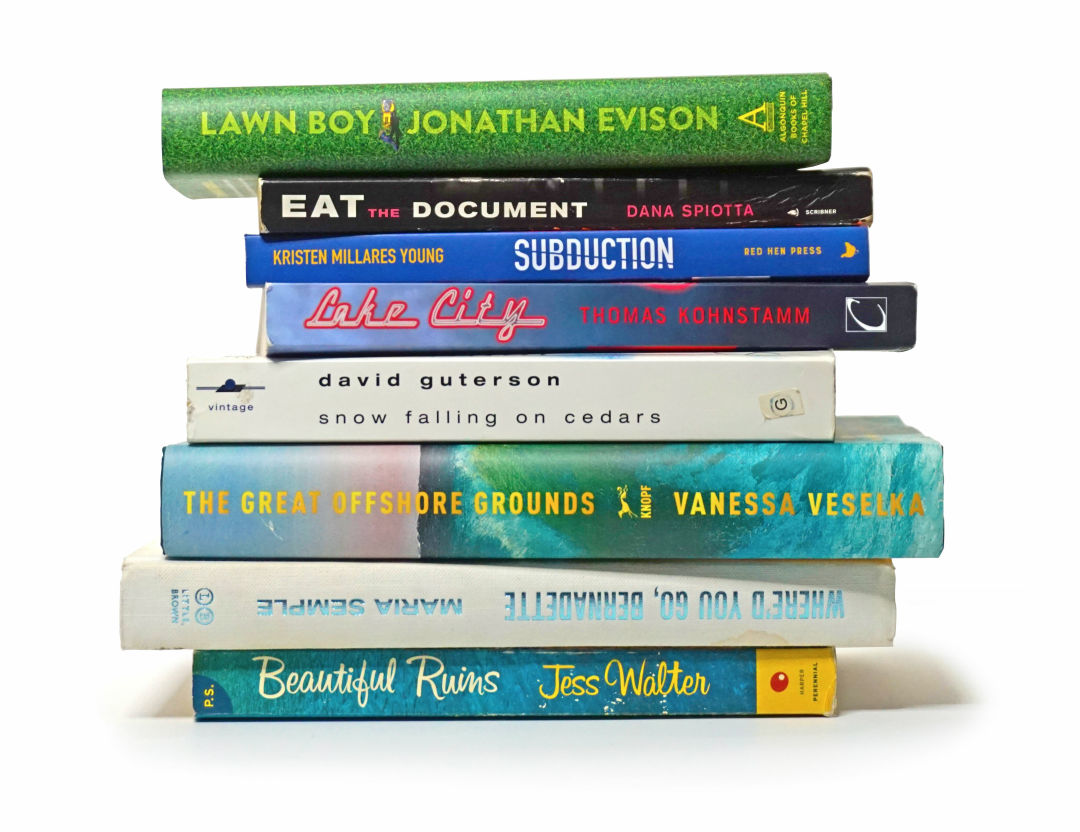

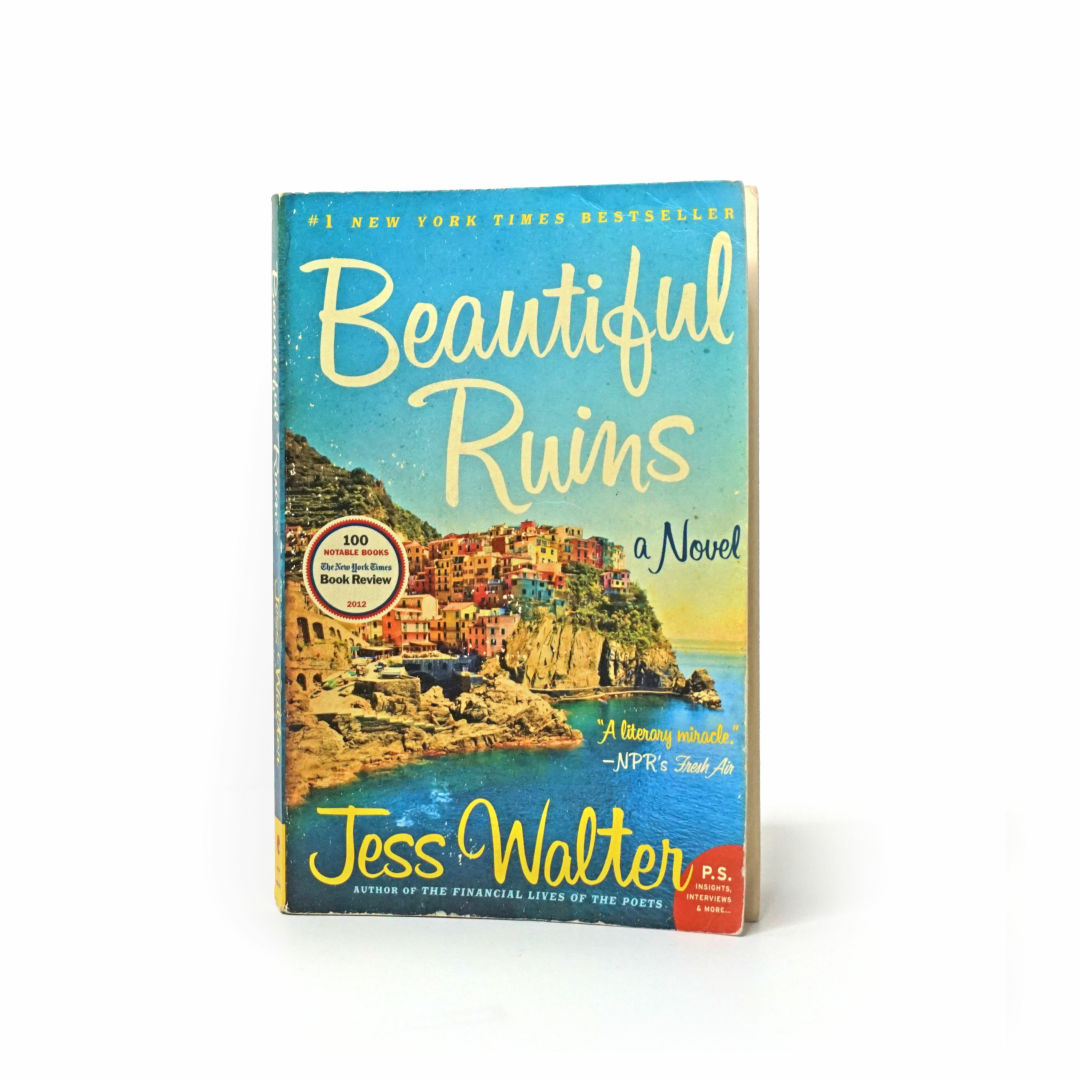

Beautiful Ruins by Jess Walter (2012)

Among the biggest blockbuster novels to come out of this state in the last decade, Beautiful Ruins sails between 1962 (a movie star has left the set of Cleopatra to sequester herself in a small town on the Italian coast) and 2012 Hollywood, where a screenwriter is trying to pitch a movie called Donner! (about the Donner Party, of course). In his sixth novel, with spectacular verve, Spokane author Jess Walter encompasses the sweep of old Hollywood and the cynical cunning of new Hollywood; it’s the most comprehensive display of his powers—for comedy, for romance, for ripping plotting—to date.

► See also Walter's The Cold Millions.

The Bird King by G. Willow Wilson (2019)

G. Willow Wilson is best known for co-creating and writing the latest Ms. Marvel comics. Her 2019 novel is both a departure (more words!) and a continuation (a big, fantastic narrative): The Bird King follows two friends, a sultan’s concubine named Fatima and a maker of magical maps named Hassan. It’s set during the Spanish Inquisition, just as the Emirate of Granada begins to fall. But Wilson is concerned just as much with the intricacies of character and relationship as she is with the grand-scale history.

Cathedral by Raymond Carver (1983)

Raymond Carver’s stories are where the literature of the Pacific Northwest becomes the literature of America. With settings as common as living rooms and diners, and with characters whose lives revolve around such low-stakes conundrums as whether or not to purchase a used refrigerator, Carver manages to capture expansive emotions in plain English. The title story, about a man’s uneasiness with his wife’s blind male friend, is alone worth the purchase price. —RB

Cryptonomicon by Neal Stephenson (1999)

Neal Stephenson’s chronicle of World War II code breaking and the rise of geek culture in Seattle appeared in 1999, just in time for Y2K paranoia and the WTO riots. It’s rooted in history, prescient, and a fabulous read, like taking the best college course of your life. And while Cryptonomicon dazzles with sheer brainiac firepower, its characters come across as compellingly human and alive. Historical figures like Alan Turing make appearances, mingling with spies and hackers, but what makes this novel such a joy are its moments of inspired, nerdy hilarity. —RB

Neal Stephenson.

Image: Wikimedia CC by Cmichel67

The Dismal Science by Peter Mountford (2014)

Told in zippy, witty prose, Mountford’s second novel follows Vincenzo D’Orsi, a middle-aged vice president of the World Bank in the mid-2000s. When faced with a choice over whether to cut off aid to Boliva, D’Orsi quits. Then he decides to give a speech in La Paz. Then the C.I.A. is involved. This is the sort of novel that’s a comedic page turner but also in discussion with Dante and Machiavelli.

Dune by Frank Herbert (1965)

Freaking sandworms, man! Widely hailed as one of science fiction’s most beloved masterpieces, this richly detailed space opera partly set on a desert planet is less known as springing from the Pacific Northwest. Herbert, a resident of Port Townsend, was inspired by the sand dunes of Florence, Oregon, to create a world in which scheming cartels battle for control of the most precious resource in the galaxy—a spice called melange that facilitates space travel and (bonus!) doubles as a hallucinogen. The novel inspired many sequels, a movie by David Lynch that bombed, and a movie treatment by Alejandro Jodorowsky that sadly never made it to the screen (a remake by Denis Villeneuve is set for release this October). –RB

Eat the Document by Dana Spiotta (2006)

In this National Book Award–nominated novel, a bombing plan by a 1970s revolutionary runs horribly awry. So the protagonist, Mary, goes on the lam. By the late 1990s, she’s living in Seattle, under another name, and has a son—and perhaps an old acquaintance nearby. Dana Spiotta, though, is not especially concerned with thriller plotting. Instead, in scalpel prose, she dissects the city’s counterculture streak: the radical bookstores, the anti-corporate protest.

Everfair by Nisi Shawl (2016)

Nisi Shawl’s 2016 steampunk novel takes as a starting point the colonial genocide in the Congo Free State between 1895 and 1908. But, in a massively intricate narrative (this is a book with a character list at the start, and short chapters jump between years and countries), Shawl reconsiders what might have been, tracing the creation of and tensions in a utopia in the Congo. The book—ambitious, immense, vivid—is a rejoinder to a terrible past and a reminder of our responsibilities in the present.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang (2019)

Bellevue sci-fi writer Ted Chiang’s 2002 collection, The Story of Your Life and Others, eventually saw its semi-eponymous novella (“The Story of Your Life”) adapted into the 2016 movie Arrival. In 2019, Chiang finally released the follow-up collection, Exhalation. Like its predecessor, the book abounds with crisp prose and ingenuity: A parrot narrator, its species facing extinction, ponders the vast silence of the universe; a product called Remem functions as a prosthetic memory.

Fledgling by Octavia E. Butler (2006)

Octavia E. Butler belongs in the sci-fi and fantasy pantheon with Ursula K. Le Guin and Isaac Asimov (for sheer greatness read Parable of the Sower). She didn’t move to the Seattle area until 1999, and she died in 2006. During that time, she wrote only Fledgling, a novel about the first Black woman in a species of vampires called Ina (this makes her able to walk in sunlight). But it’s clear from the opening pages—in which the narrator, Shori, awakes after a head wound in a rainy Northwest forest—that the region had already seeped into Butler’s consciousness.

The Girl with Brown Fur by Stacey Levine (2011)

Levine is one of our most idiosyncratic and unsettling prose writers, and absurdity reigns in her story collection The Girl with Brown Fur. Her first lines make it impossible to not read her second lines. For example, “Imagine being a bean: a pale supplicant, rimy dot, a belly-wrinkled pip, lying enervated on the kitchen chair, trying too hard all the time.” Levine’s are stories that aren’t so much read as succumbed to. She makes the English language sound new, and while she rightly belongs in the company of other fantasists like Aimee Bender and Judy Budnitz, her masterful manipulation of creepy atmospherics sets her apart. –RB

The Great Offshore Grounds by Vanessa Veselka (2020)

The former Seattleite and current Portlander’s second novel starts with two adult half sisters heading to their estranged father’s wedding outside of Seattle (for the free refreshments). That kicks off a U.S.-spanning epic as the pair tries to uncover the truth about their different mothers and the stories they’ve heard about them.

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon (1973)

Oh, sure, you started it once in college and it defeated you. But there’s no denying the lasting pleasures of this confusing and arousing romp through the aftermath of World War II with one of America’s most enigmatic former Boeing technical writers. Thomas Pynchon made his home for a time in the University District, but it feels a bit disingenuous to claim him as a Seattle writer, particularly since for long stretches of his career no one knew where he lived at all. Either way it’s hard to imagine this 770-page hallucinatory monster existing without the influence of the kind of rocket science the Pacific Northwest spent much of the twentieth century dropping on the world. –RB

Hollow Kingdom by Kira Jane Buxton (2019)

Crows are a big deal in Seattle. Rarely, though, do they get to verbalize their role. This debut comic novel by Kira Jane Buxton changes that: S.T., a domesticated crow who calls humans MoFos and loves Cheetos (who can imagine a couth crow?), narrates as people fall apart around him. Quite literally. The MoFos are becoming zombies, which S.T. first senses when one’s eyeball falls out.

Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford (2009)

This novel tells the story of two pre-teens, Chinese American Henry Lee and Japanese American Keiko Okabe, who live on opposite sides of Chinatown–International District during World War II. Centering on the Panama Hotel, which still stands at Sixth and Main, the book leaps between 1986 and wartime Seattle, when the young Henry falls for Okabe only to see her sent with her family to the incarceration camp at Minidoka.

Homebase by Shawn Wong (1979)

University of Washington creative writing professor Shawn Wong got his start with this slim, emotionally rich account of a first-generation Chinese boy coming to accept his adopted country. The novel itself could serve as a master class on tone and lyricism. Wong plays with subtle, repeating motifs and creates one arresting image after another. The result is somehow both life affirming and haunting, as in passages about the suicides of hopeless Chinese expats stranded within America’s immigration system. This is the sort of novel that sticks with you for years and years. –RB

Lake City by Thomas Kohnstamm (2019)

After his rich New York wife cheats on him, Lane Bueche tumbles home to Seattle’s Lake City to stay with his mom, waiting for things to settle down. While at a bar one night Lane meets Nina, a well-off California transplant who wants to get sole custody of her and her partner’s foster child. The birth mother, Inez, wants her son back, and a judge has ruled for split custody. Nina offers Lane $3,000 to try to sabotage Inez’s sobriety. If some of the social commentary reads pat, Thomas Kohnstamm has a zippy sense of plot, a fine eye for detail, and a flair for casually acerbic description—it’s darkly funny light reading. Full review here.

Lawn Boy by Jonathan Evison (2018)

Jonathan Evison’s fifth novel (following The Revised Fundamentals of Caregiving and This Is Your Life, Harriet Chance!) is an engaging and energetic inquiry into class, race, sexuality, economics, and growing up. Mike Muñoz—a 22-year-old self-described “tenth-generation peasant with a Mexican last name, raised by a single mom on an Indian reservation”—lives on Bainbridge and is something of a topiary wunderkind for a landscaping company until he gets fired for flinging dog poop at his employer’s window. What unfolds is a bildungsroman of odd jobs and misadventures.

Kim Fu.

Image: Courtesy Daniel Harasymchuk

The Lost Girls of Camp Forevermore by Kim Fu (2018)

The second novel from Kim Fu (after 2014’s For Today I’m a Boy, about a transgender boy in a family of Chinese immigrants in Canada) begins as a typical summer novel, about a group of girls at Camp Forevermore in the Pacific Northwest. Fu even mimics the cadence of the YA section: “Siobahn wanted to be more like the heroines of the books she liked, about girl detectives and girl adventurers.” But on a kayaking trip, tragedy strikes. And the novel slips between camp and the girls’ adult lives, becoming not a summer coming-of-age story but a look into how childhood hurt echoes and echoes.

Magic City by Jewell Parker Rhodes

Jewell Parker Rhodes’s 1997 novel Magic City tells the long-neglected story of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, when white mobs brutally razed the city’s flourishing Black community and left as many as 300 people dead. In observance of the 100th anniversary of the massacre, the novel has been reissued. It centers on a young Black man whose dreams of escape (in many senses of the word) manifest in hero-worship of Houdini. The screams of a white woman, who has been raped by her father’s farmhand earlier that morning and is suffering the traumatic aftershocks, are all it takes to place Joe in the crosshairs of a lynch mob and ignite the powder keg of white supremacist violence in Tulsa. Parker Rhodes writes of this intersection of patriarchal violence and white supremacy with uncompromising clarity. —Sophie Grossman

The Mermaid from Jeju by Sumi Hahn (2020)

This novel follows Junja, a young haenyeo (the island’s famous female free divers) on the Korean island of Jeju as World War II ends. On an errand to fetch a pig, Junja meets and falls for a young boy in the mountains, but upon returning home, she finds her mother beaten to death. The book follows Junja and her grief through the years, from the political tumult as Japan ends its occupation of Jeju, to Junja leaving the island herself.

Middle Passage by Charles R. Johnson (1990)

A longtime University of Washington professor, Johnson won the National Book Award for this novel, which he saw as “first and foremost, at least for me, a sea adventure story, a rousing sea adventure story.” Perhaps that’s surprising for a lauded literary novel. Or perhaps not, given that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Moby Dick were both aqueous adventures with race at the fore. In some ways, Johnson’s work recalls both—Melville’s allusive verbal vim and mythic gravitas, Twain’s acid humor. Here our narrator is Rutherford Calhoun, a freed slave and erudite scoundrel who, in order to avoid marriage, hops a ship in New Orleans. This ship, the Republic, happens to be a slaver, on its way to Africa, and Calhoun occupies a complicated place in its hierarchy—neither slave nor white crew. The book on its surface is a swaggering, seafaring narrative, but just beneath lies a serious inquiry into what things like “freedom” and “republic” actually mean in a country with so horrific a history.

The Moon and the Sun by Vonda N. McIntyre (1997)

One of the particularly luminous stars in the Pacific Northwest’s constellation of sci-fi writers, McIntyre became, with her novel Dreamsnake, the third woman to win a Hugo Award for best novel, and the second to win a Nebula. That book is now out of print, but The Moon and The Sun also won a Nebula. In this fantastical alternate history, King Louis XIV dispatches a philosopher-priest to go get a sea monster that might make him immortal.

No-No Boy by John Okada (1957)

In John Okada’s 1957 novel, a young Japanese American in Seattle resists the World War II draft (responding “no” twice in a government questionnaire). He goes to a camp for two years, and prison for another two. When he returns to Seattle, he’s met with the scorn of his family and feels “like an intruder in a world to which he had no claim.” Okada, a Seattleite himself, parses the complexities of identity in Seattle’s Japanese American community during a dark moment in this country.

One Two Three by Laurie Frankel (2021)

A company called Belsum Chemical opened a plant in the tiny, fictional town of Bourne. The runoff poisoned the town’s water. Tumors bubbled on dogs. Sickness hit the people: migraines, miscarriages, birth defects, disabilities, deaths. Eventually the plant left. But 17 years later, the three Mitchell triplets—Mab (One), Monday (Two), Mirabel (Three)—are products of this environment. Monday is on the autism spectrum and Mirabel was born unable to speak or move most of her limbs. In alternating chapters, the three narrate Seattle writer Laurie Frankel’s full-hearted, ecological fable, which finds the sisters fighting Belsum’s return. Full review here.

Pigs by Johanna Stoberock (2019)

This grim, weirdo allegory—a little Lord of the Flies, a little Animal Farm—sets us down on a dystopian island inhabited by pigs that eat the world’s refuse: toasters, radioactive waste, toenail clippings. Four kids also live here, moving this garbage from the coast to the pigsty. Some adults also occupy the island as a ruling class. Then people start arriving amid the trash. As you might guess, the morality of feeding them to the pigs is rather fraught.

Riots I Have Known by Ryan Chapman (2019)

During a prison riot he (perhaps) provoked, this slim novel’s unnamed narrator locks himself inside the Will and Edith Rosenberg Media Center for Journalistic Excellence in the Penal Arts. He’s writing a final dispatch: part editor’s note, part confession, part scabrous ramble. University of Puget Sound–alum Ryan Champan’s first novel reads—in the very best way, all zooming sentences and layered, erudite jokes—like Nabokov live-blogging a prison riot.

Skinny Legs and All by Tom Robbins (1990)

Goddamn has Tom Robbins given us a body of work. If you haven’t read this former Seattle Times art critic yet, start with Skinny Legs. He keeps his absurd conceits (inanimate objects discover how to travel across America) at a high boil, while meditations on the world’s common religious traditions simmer on the back burner. This is the book where the linguistically bonkers gusto of his 1970s novels began to accommodate more serious and lasting themes. –RB

Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson (1994)

A lyrical courtroom drama, Guterson’s first novel is set on a fictional San Juan island “of five thousand damp souls.” It is 1954. A fisherman was found drowned in his own net, and Kabuo Miyamoto, a Japanese American fisherman, is on trial for the murder. World War II, and its incarceration camps, are not long gone, and Guterson presents a layered look into the ways the past haunts.

Subduction by Kristen Millares Young (2020)

A longtime local journalist and essayist, Kristen Millares Young’s first novel, Subduction, is set in Neah Bay and follows a Latina anthropologist as she escapes her broken marriage to live on the Makah Indian Reservation. There, she falls into another fraught romance with the troubled Peter. The prose is at once poetic and punching. Full review here.

Truth Like the Sun by Jim Lynch (2012)

This sweeping novel examines the inciting incident of Seattle’s futurism: the 1962 world’s fair, which gave us the Space Needle. The book bounces between the fair and a plot about a journalist in 2001 investigating Roger Morgan, the fair’s mastermind who’s now running for mayor. Through that, Lynch charts the rise of a city and its accompanying travails.

Vera Violet by Melissa Anne Peterson (2020)

A sense of grim drama suffuses this debut novel. You can feel it in the setting: Shelton, Washington, the logging town out on the peninsula. Feel it in the plot: about a group of teens, centered on the narrator Vera Violet O’Neely, dealing with the roughness of rural Washington, its meth and violence. Feel it in the taut sentences: “I beat the boy after school. I did not say a word before or after. I beat him because he stood against the brick wall alone like he was a fighter.”

We Had No Rules by Corinne Manning (2020)

All 11 stories in Manning’s debut collection are narrated in a similar voice, by a queer character, in first person. That “I” shifts as you move through the book—similar but never the same. Many stories center on breakups, a few on divorces. Some bring back characters from earlier. Yet these repetitions are not failures of imagination but the book’s form, a way to peel back layers of identity—particularly queer identity. Throughout, Manning does so with clarity, intelligence, humor, wisdom, and warmth. Full review here.

Maria Semple.

Where’d You Go, Bernadette by Maria Semple (2012)

Seattle satirist Maria Semple’s breakthrough novel is a flurry of contemporary, epistolary wit. Passive aggressive e-mail threads, report cards, personal-assistant bills—all converge in a biting look at Queen Anne’s chard-growing, Microsoft-employed privilege. Let it stand as testament: We all don’t take ourselves that seriously.

Memoir

Altitude Sickness by Litsa Dremousis (2014)

The existence of this gutsy little e-book is owed to a tragedy—a climbing accident that took the life of Litsa Dremousis’s onetime lover and friend. Coming in at 10,600 words, this emotionally fraught memoir punches well above its weight, revealing a writer willing to confront brutal, uncomfortable truths. –RB

The Fixed Stars by Molly Wizenberg (2020)

In 2015, Molly Wizenberg got a jury summons. At the trial—even though she was 36 and married to a man and supposedly “straight enough to not think about whether I was straight”—she felt an attraction to a female defense attorney, a true crush, unavoidable and overwhelming. Leaving, she heard a refrain from her sandals on the sidewalk: “Who am I, who am I. Who am I?” For the rest of The Fixed Stars, Wizenberg attempts to answer that question, starting with a relentless inquisition into her identity. Eventually, her marriage dissolved and she identified as queer. The draw of Fixed Stars is that, in a tone of polished conversation, she takes us with her, revelation by revelation.

The Freezer Door by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore (2020)

Call it a memoir; call it a strobing, fragmentary novel. The book follows Sycamore’s thoughts and experiences in Seattle, exploring queerness, gentrification, fluidity, community (in all its contradictory particulars), and trauma. It is at once funny and piercingly sincere. See, for instance, a series of dialogues between an ice cube and its ice tray: “Everybody likes me when I’m cold, says the ice cube tray. I want to be fluid, says the ice cube. Hold me.”

A House on Stilts: Mothering in the Age of Opioid Addiction by Paula Becker (2019)

Local writer and historian Paula Becker’s memoir takes its name from the “tree house with no tree” in her backyard where her son Hunter played as a kid and where, after he became addicted to opioids as a teenager, he camped out. A House on Stilts is most valuable for its look at how addiction can rend not only a life, but a family. Becker charts in painful, probing detail her own psychology as she tries to reckon with what’s taken hold of her son.

I’m in Seattle, Where Are You? by Mortada Gzar

In 2016, novelist Mortada Gzar came to Seattle seeking Morise, an American GI he’d met and fallen for years before at the University of Baghdad. Here, he moved into a house with three gay men. Walking the city, he recollects the life that brought him to Seattle. He grew up in Iraq under Saddam Hussein’s regime and had been imprisoned for his homosexuality after meeting Morise. Gzar's writing comes with a surreal tinge: “Notions, ghosts, bits and pieces of stories invaded my head and occupied my mind while his name pursued me like the evening shadows no one sees…. Lenin’s statue greeted me, but with a woman’s voice.”

The Magical Language of Others by E.J. Koh (2020)

A couple years ago, the local poet E.J. Koh began handwriting love letters to strangers, with the aim of eventually reaching thousands. Her memoir The Magical Language of Others inverts this conceit—responding, in a way, to long-unanswered letters from her mother, who moved back to Korea when Koh was 15. The resulting book parses how and what language means, across continents and generations, in the sort of prose that poets achieve—lapidary and evocative.

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood by Mary McCarthy (1957)

Mary McCarthy should sit cover to cover with, oh, Saul Bellow, as an ambitious, frank, and piercing cataloguer of the mid-century American psyche. Just see her sweeping 1963 novel The Group. That she isn’t included in such company may owe partly to the fact that she was a woman, and wrote about them. She was also born, and mostly raised, in Seattle, and this memoir from 1957 recounts her youth with characteristic, and sometimes scalding, flair: “Our father had put us beyond the pale by dying suddenly of influenza and taking our young mother with him, a defection that was remarked on with horror and grief commingled, as though our mother had been a pretty secretary with whom he’d wantonly absconded into the irresponsible paradise of the hereafter.”

My Body Is a Book of Rules by Elissa Washuta (2014)

Memoirs that traffic in tales of depression and substance abuse often come across as though the author is fishing for attention and sympathy. Elissa Washuta’s My Body Is a Book of Rules transcends the tropes of the genre by virtue of the unsentimental strength of her prose. She’s reflective without being solipsistic, insightful without being pedantic, and wise beyond her years. Formerly an adviser for the University of Washington’s native studies program, Washuta claims membership in the Cowlitz tribe, and she explores her native identity as thoughtfully as she considers her bipolar nature. –RB

► See also Washuta's White Magic

Elissa Washuta during her tenure as a Fremont Bridge writer-in-residence.

Image: Mike Kane

My Unforgotten Seattle by Ron Chew (2020)

Ron Chew spent a decade at Seattle’s International Examiner newspaper (mostly as editor). Here he turns his journalistic skills on his own past—like his grandfather’s emigration from China (“I grew up under this cloud of silence, with no mention of my grandparents”)—and that of this city, including how he campaigned to turn a hotel into the current Wing Luke Museum, where he served as executive director.

My People Are Rising: Memoir of a Black Panther Party Captain by Aaron Dixon (2012)

In 1968, when he was 19, Aaron Floyd Dixon founded the Seattle chapter of the Black Panther Party. His 2012 memoir encompasses his family’s history (going back to what little he knows of his great-great-great-grandmother Mariah, a slave in Mississippi), his childhood in Seattle’s Madrona, and his political activism and radicalization—hearing Martin Luther King speak, having James Brown write $500 checks to the party in his hotel room, firing a shotgun and having it tear his arm “almost in two”—and the Panthers’ split. Cover blurbs should be taken with a grain of salt. Even so, a blurb from Cornel West might impel you: “Aaron Dixon is a courageous, compassionate, and wise freedom fighter whose story of his pioneering work in the Black Panther Party is powerful and poignant.”

Nisei Daughter by Monica Sone (1953)

Monica Sone was born Kazuko Itoi, and in this memoir she explores the complexities of dueling identities. Nisei Daughter is the story of a second-generation Japanese American (also known as nisei) coming of age in Seattle’s Japantown in the years before World War II. Coinciding with the internment of around 120,000 people of Japanese descent is Kazuko’s unfolding sense of self. “I felt nothing unusual stirring inside me,” she writes when her mother explains Kazuko’s Japanese lineage. –SL

Swimming to Freedom: My Escape from China and the Cultural Revolution by Kent Wong

His father was a Chinese official, but when the Cultural Revolution hit, Kent Wong and his siblings were separated into different villages. Eventually, he’d join an underground movement and become one of a half million who fled to Hong Kong via an open water swim that in some spots stretched six miles. His trip ultimately took him to Seattle. He recalls that journey in clear, direct prose in this memoir. You can read an excerpt here.

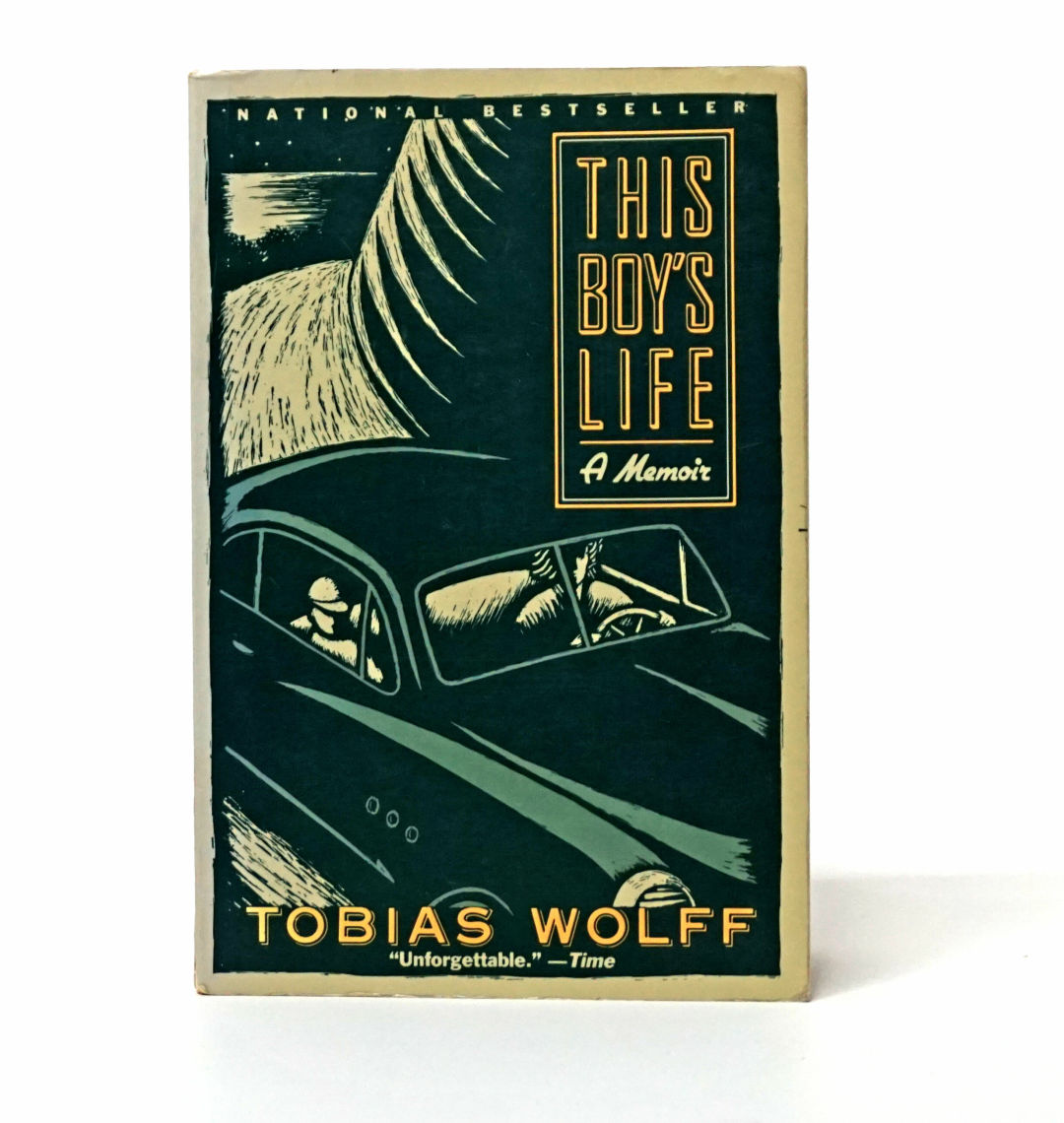

This Boy’s Life by Tobias Wolff (1989)

When his parents divorced in the early 1950s, young Tobias Wolff found himself stranded in Seattle with his mother, who soon paired up with a backwoods bully named Dwight. In this legendary memoir, Wolff recounts the time he spent living with Dwight in Concrete, where he suffered abuse, fell in love with basketball, and forged his own high school transcripts in a successful attempt to escape to a private boarding school. The career that resulted—Wolff won a PEN/Faulkner award for fiction and has taught at Stanford and Syracuse—arguably justifies his deceptive ploy. Besides, what a fantastic story. –RB

Poetry

All Its Charms by Keetje Kuipers (2019)

This collection from San Juan Islands–based poet Keetje Kuipers centers on a few key life events—her decision to become a single mother, her marriage to a woman she loved years before—but those are like prisms the poems radiate from. The book becomes not only about birth and living and loving, but also about death and time and loss. What fuses this together is Kuipers’s precise voice, light in touch and resoundingly constant. The book contains only 52 poems and they rarely reach a page’s bottom, yet when you read them together, you feel as if you’ve been moved through a life.

Ceremony for the Choking Ghost by Karen Finneyfrock (2010)

Every line counts and every line surprises. Karen Finneyfrock’s poetry is beautiful because it achieves this rare blend of economy and novelty. Pick up her Ceremony for the Choking Ghost and prepare your senses for funny, piercing, and vividly imagined poems. In her spare time she pens funky, cool YA books like Starbird Murphy and the World Outside and The Sweet Revenge of Celia Door. With Ceremony you get closest to the flame of Finneyfrock’s talent. –RB

The Collected Poems of Theodore Roethke by Theodore Roethke (1961)

Many legions of poets have exalted nature as they stared down existential darkness (it’s kind of their thing). For Theodore Roethke—whose poem “My Papa’s Waltz” graces nearly any anthology of American poetry—this darkness included a troubled childhood and a struggle with bipolar disorder. But he, as much as anyone, wielded rich wisdom like a fist to the chest. “God bless the ground! I shall walk softly there, / and learn by going where I have to go,” he wrote in “The Waking,” the title poem in his 1953 collection that won him a Pulitzer. Roethke taught at the University of Washington from 1947 until he died in 1963, also snagging a couple National Book Awards. In the state, and in the nation, Roethke is a titan.

Cool, Calm, and Collected by Carolyn Kizer (2001)

A polyglot and Pulitzer Prize winner, Spokane-born Kizer’s career got rolling when she landed a poem in the New Yorker at age 17. It culminated here, in this 520-page collected works. What emerges most in these poems from 1960 to 2000 is Kizer’s political occupation, with feminism and civil rights, and her voice—precisely ironic and suddenly generous. She was someone seeking to, as she wrote, “observe the world with desperate affection.”

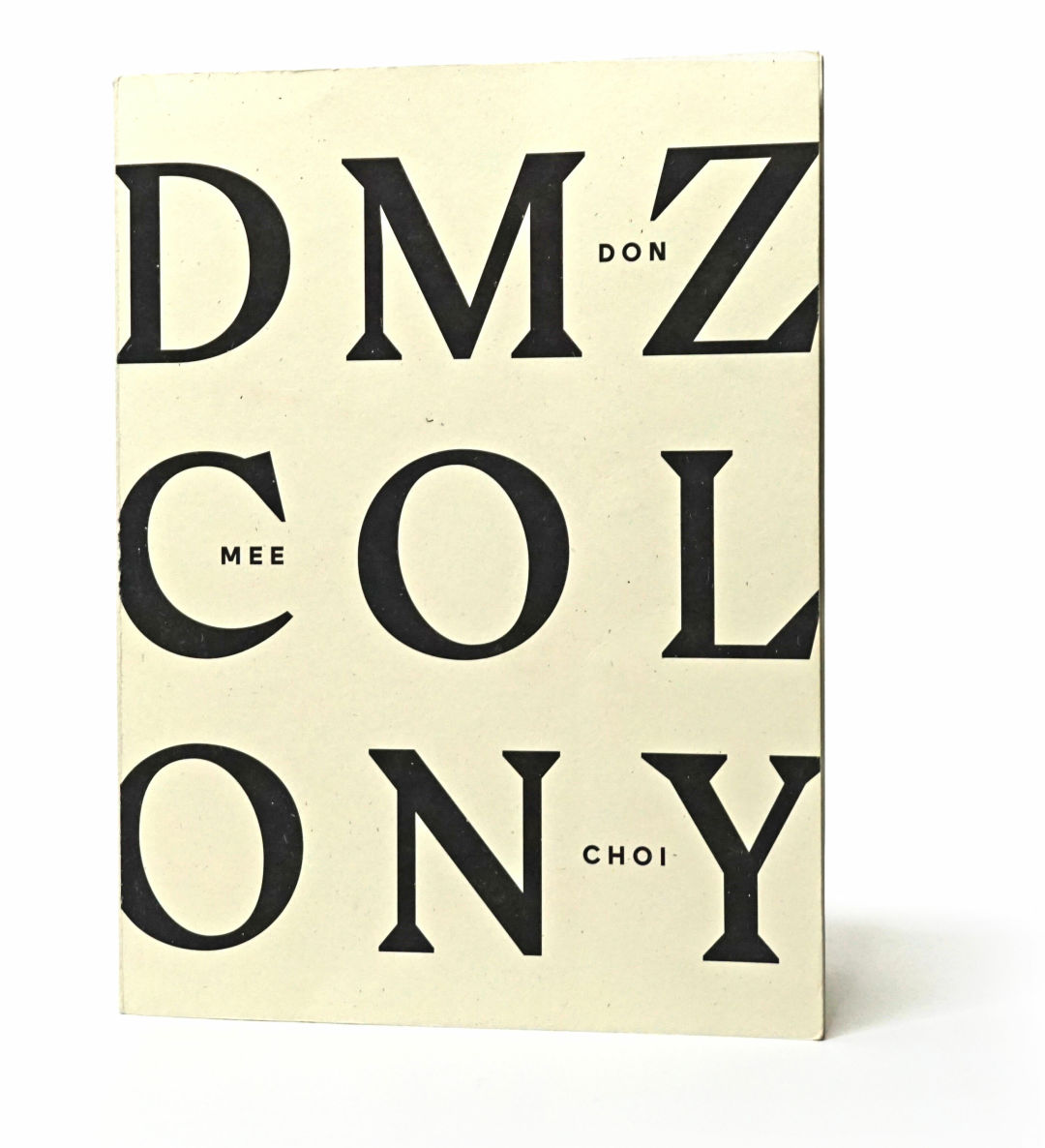

DMZ Colony by Don Mee Choi (2020)

Winner of the National Book Award for Poetry, DMZ Colony takes its name from Korea’s 2.5-mile-wide Demilitarized Zone between North and South, “one of the most militarized borders in the world.” In that sense, it’s a rejoinder to atrocity, an interrogation of colonialism and neocolonialism, a book that creates a new language to reverse the words of empire. It’s a book-length event, a constellation of photographs, drawings, prose, quotation, transcribed interview, imagined monologues in Korean and English. It’s not easy reading, but if you’re up for the challenge, the rewards are mesmerizing and powerful.

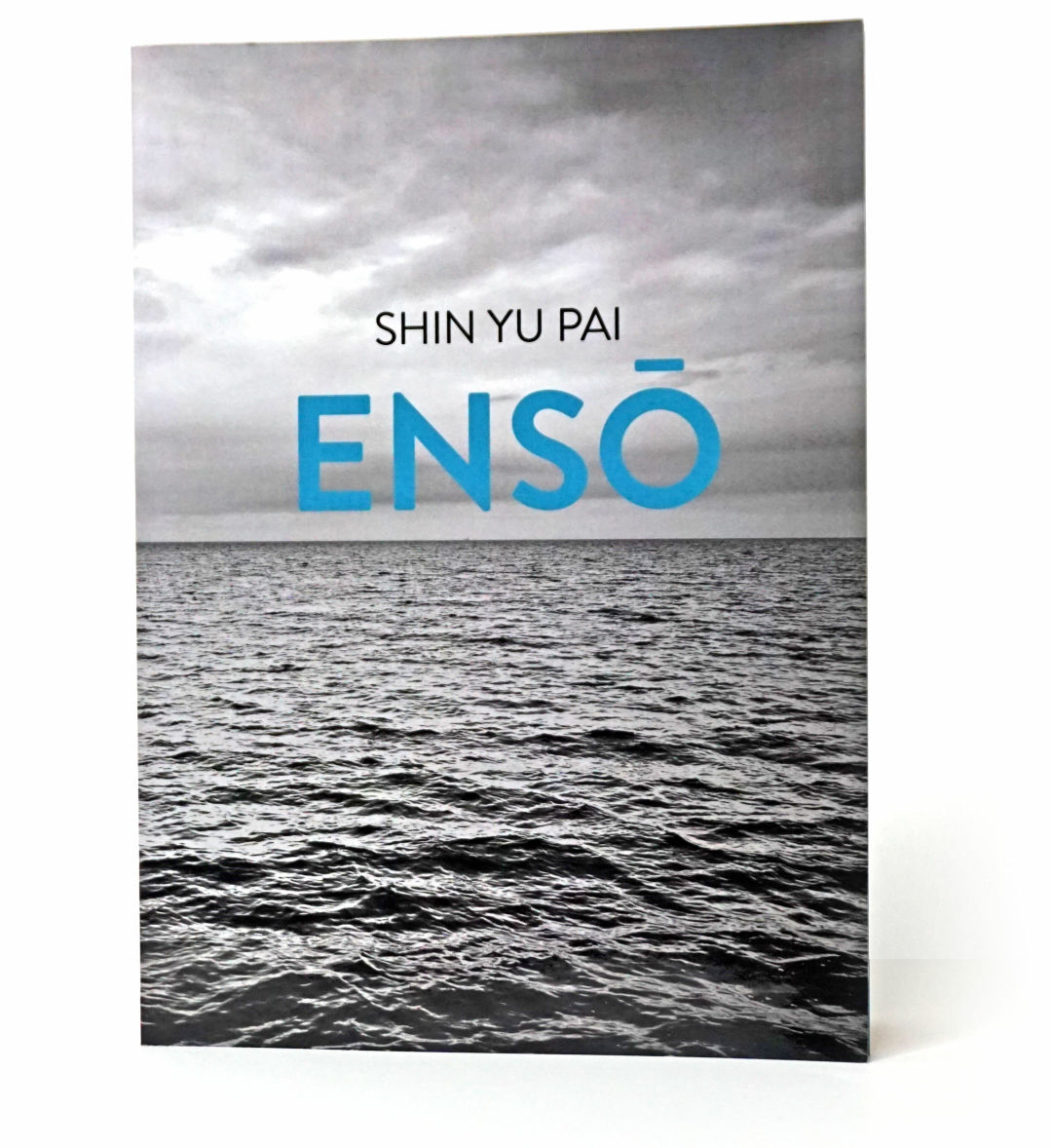

Ensō by Shin Yu Pai (2020)

In her eleventh book, unsurprisingly, local poet and photographer Shin Yu Pai looks back. Ensō unreels in a pastiche of essays, lyric poems, and visual art (including the covers of her former books and images imprinted on leaves). On one level, it’s a 20-year survey of her work to date. On another, it becomes the narrative of that work’s creation, showing, for instance, how visits to a gallery at the Art Institute of Chicago led to a poem about a 120-year-old Japanese work of ink on paper.

The Galleons by Rick Barot (2020)

Tacoma-based poet Rick Barot’s fourth collection centers on the Manila galleons, ships that from 1564 to 1815 sailed between the Philippine capital and Mexico. Its 10 titular poems become vessels themselves for his associations with the ships—of the trade itself, of present-day U.S. capitalism, of his own and his family’s immigrations from the Philippines, of the loss of his grandmother. The rest of the book’s poems, all of it unfolding in couplets, are just as discursive and exquisitely controlled.

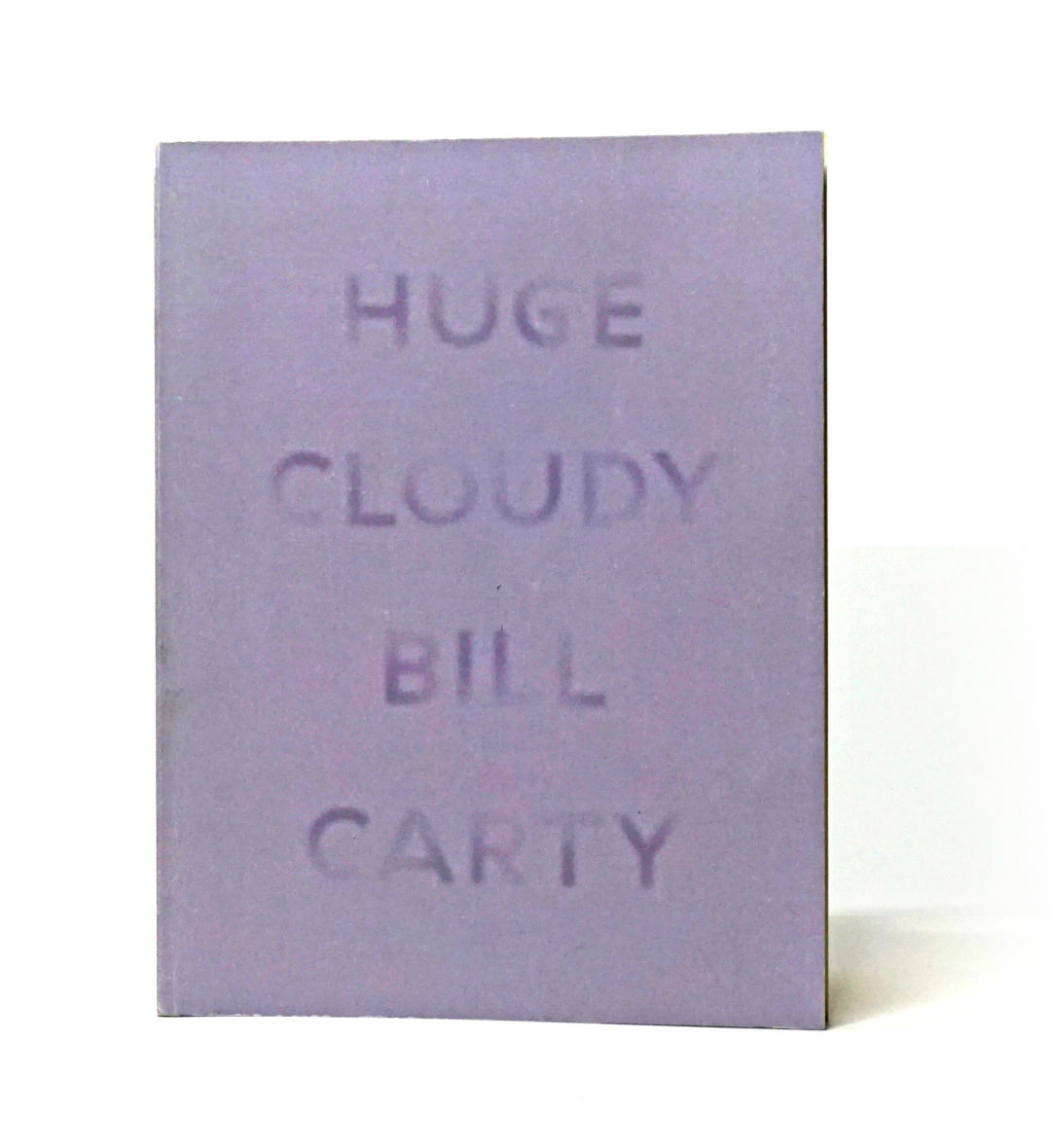

Huge Cloudy by Bill Carty (2019)

This debut collection from local poet Bill Carty is perhaps best typified by the lines that open “Constellations” about halfway through the book: “I’m eating duck with pleasure / in a borrowed gray suit / at one of those ‘bury me / in drink’ funerals because the airline / lost my luggage / somewhere over Nebraska, / and this funeral won’t stop losing / my friend.” Which is to say, Huge Cloudy is conversational but verbally limber, and mordantly funny but suddenly heartfelt.

Instruments of True Measure by Laura Da’ (2018)

The second collection of poems from Da’ begins like this: “I am a citizen of two nations: Shawnee and American. I have one son who is a citizen of three. Before he was born, I learned that, like all infants, he would need to experience a change of heart at birth in order to survive…. Our new bodies obliterate old frontiers.” Working often in lucid couplets, Da’ carries attention—to history, to “old frontiers” and our distortions of them—through the book to make us look anew at the maps and stories the U.S. carries.

Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices by Claudia Castro Luna (2017)

In this book, Castro Luna, a former Seattle Civic Poet and Washington State Poet Laureate, composes an elegy to the “women and girls killed in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.” Each brief poem is named for a different María—“María Agustina Mystical Rose” or “María Santos Sweetest Apple”—that Castro Luna found on a list of hundreds of disappeared women. The resulting 45 poems reckon with loss variously, raging here and beatific there. “The light left your eyes, Luz,” she writes, “you, who were enshrined in it at birth / for some women / light—lux, is luxury / spilled from untold pores.”

Making Certain It Goes On by Richard Hugo (1991)

We needn’t blame the house alone for Richard Hugo’s preeminence in Seattle’s poetic canon. The guy’s life was tied to this state. He grew up in White Center; he went to the UW; he worked for Boeing. His poetry, with its tight syllables, was suffused with nature (we love nature) and what gets called a “sense of place,” which was, mostly, here. This omnibus gathers his career between two covers.

Opting Out by Maged Zaher (2017)

His poems ping between ribald longing and corporate doublespeak, between Cairo (his birthplace) and Seattle (his home for many years), between the politics of empire and those of desire. Their lines are short, jittery, juxtapositional, often very funny. All that is on full display in this collected works that spans 15 years.

Overpour by Jane Wong (2016)

Overpour unfurls in a montage of sometimes lovely but often brutal imagery (here be bones and animal blood). It is, like local Jane Wong’s growing body of work, engaged with peeling back the manifold layers of self, with feast and famine, with her family history of poverty in China and American pastoralism: “Sometimes, I think: Can Walden exist in China? / Returning to nature is a luxury we keep.”

Jane Wong.

Patriarchy Blues by Rena Priest (2017)

After an inquisitive barrage (“To hide from oneself? To hide from others?”), the first poem in Patriarchy Blues ends like so: “To be destroyed, / and rebuilt by songs.” It feels like a guiding light at the outset of current Washington State poet laureate Rena Priest’s first book. With wry irony, she cuts into the ruined heart of patriarchy and sets about stitching a ventricle or two.

Revenge of the Lawn by Richard Brautigan (1971)

Richard Brautigan suffered through a dreary childhood of hardships in Tacoma but is most often associated with the rollicking San Francisco poetry scene of the 1960s. He was our most brazen literary mad scientist, a poet turned prose stylist whose absurdist scenarios suggested a more user-friendly Donald Barthelme. Revenge of the Lawn, a collection of short stories, is a good entry point into the oeuvre of this horny and thorny lover of language. The story “1/3, 1/3, 1/3” finds a trailer park trio conspiring to write a novel in the most idiotic way possible. Hilarious.

Salat and Here I Am O My God by Dujie Tahat (2020)

These chapbooks by Seattle poet Dujie Tahat serve as auspicious introductions. Salat finds its forms in Muslim prayer. In both books, Tahat’s sensibility is living and elastic, moving in a line between the registers of speech and scripture (a father is “an Ibrahim with all ’80s swagger”), between lamentation and praise.

The Slip by Kary Wayson (2020)

Seattle poet Kary Wayson’s words have such a particular, spectacular syllable beat, you may want to compare the poems in her new collection The Slip to clocks or watches. But the metaphor also communicates how consistently she swerves and, paradoxically, surprises you—with humor, or a cool snap of wisdom: “I used to think of people, of lovers / of me as ways / to take. I’d take / a way. Each way seemed to seal off the others.”

This Glittering Republic by Quenton Baker (2016)

It is rare that a debut book arrives with as much assurance as Quenton Baker’s first poetry collection. That assurance appears in Baker’s command of meter and beat (when young, he was a rapper—and can do ecstatic things with monosyllables), in the rigor of his thought, and in his focus on the many facets of American Blackness.

Ugly Time by Sarah Galvin (2017)

Sarah Galvin’s poems can feel like lists of absurdist non-sequiturs. But then you realize that random nonsense doesn’t make you laugh this constantly, and it doesn’t so suddenly and deeply knife you with thought and feeling—that demands Galvin’s sneaky finesse.

(v.) by Anastacia-Reneé (2017)

The best of the very good three-book salvo poet Anastacia-Reneé unleashed in 2017, (v.) flaunts in spades the quality all writers covet—genuine imagination. A poem begins like an index (“h. / hell / heliotrope / heaven / hymen”), then swerves and becomes something grander, a dazzling account of the sounds and meanings embedded in words. The entire collection feels experimental but engaging, fragmentary but cohesive. It’s a serious look at queerness and Blackness and humanness that’s wonderfully funny.

Anastacia-Reneé.

Image: Joshua Huston