When Swedish archaeologists in 2015 X-rayed the remains of a 17th-century bishop, they were shocked when the images revealed that the bishop shared his coffin with the remains of a stillborn premature baby. Now, ancient DNA analysis has revealed that the fetus was likely the bishop's grandson, according to a new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Born in Copenhagen in 1605, Bishop Peder Winstrup was a prominent church figure in Denmark and Sweden during his lifetime, who helped found Lund University in 1666 while deftly navigating the constantly shifting political environment. (He was ennobled by the Swedish king, Charles X Gustav, when his diocese passed from Danish hands in 1658.) Winstrup died in late December 1679 and was buried in Lund Cathedral in January 1680. When his coffin was opened in the early 19th and 20th centuries, the body was remarkably well-preserved.

So when the curators of the Lund University Historical Museum heard, in 2012, that the bishop's coffin would be moved to a new burial site outside the cathedral, they joined with scientists in a multidisciplinary collaboration to study the bishop's remains before they were reinterred. The body was X-rayed and CT-scanned, along with the bishop's clothing, various artifacts, and plant and insect remains.

The scientists found that the bishop's body had not been embalmed. Rather, the body was placed on a mattress stuffed with herbs (like juniper and wormwood), with the head resting on a pillow of hops, which helped preserve it—including the bishop's clothing, although the colors had faded. They also found that Winstrup likely died of pneumonia and that he suffered from gout, arthritis, arterial plaque, and gallstones (a sign of a diet high in fatty foods), among other illnesses. He had also lost many teeth, and those that remained showed signs of decay, indicating the bishop was fond of sweets. (The coffin contained a small pouch holding several teeth.)

The bishop's lungs also proved to be remarkably well-preserved, and anthropologists found small calcifications in those lungs—evidence of a prior infection, most likely tuberculosis. The anthropologists surmised that Winthrop likely contracted the disease during the so-called "White Plague" epidemic that swept through Europe in the 17th century. In fact, last year, researchers at Lund University, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and the Swedish Natural Historical Museum were able to reconstruct the genome for a TB sample (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) taken from one of those calcified nodules. Because the bishop's precise date of death is known, the team was able to determine that the TB pathogen is much younger than scientists previously believed.

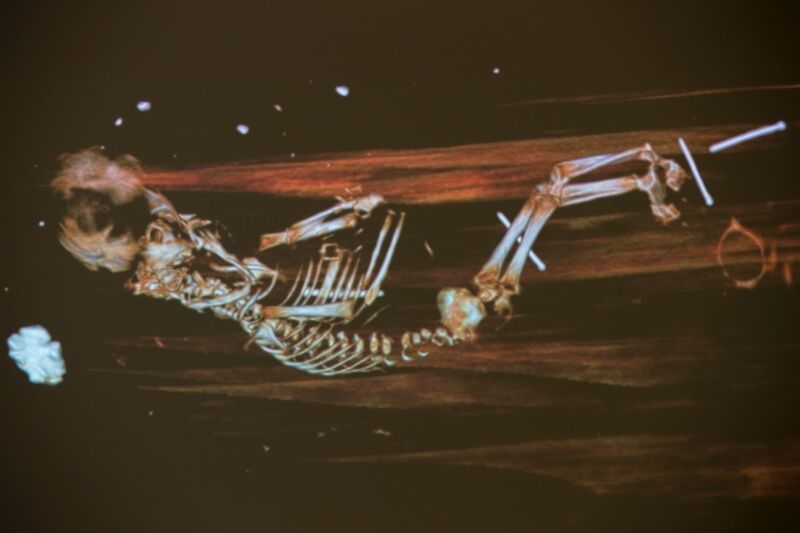

But by far the most significant discovery was that the bishop was not alone in his coffin. The CT scans showed a linen-wrapped bundle containing the remains of a stillborn fetus (roughly five to six months along, in terms of development), nestled within the layers of herbs just under the bishop's right tibia. It was initially assumed that someone (unrelated to the bishop) had taken advantage of the bishop's burial to ensure their illegitimate offspring was buried on sanctified ground.

-

Bishop Peder Winstrup on a contemporary engraving printed in one of his own theological works in 1666.

-

Peder Winstrup in the coffin, where researchers also discovered a fetus wrapped in a bundle between his calves.Gunnar Menander

-

The bundle found at the feet of the remains of Bishop Peder Winstrup.Gunnar Menander

In fact, "It was not uncommon for small children to be placed in coffins with adults," said Torbjörn Ahlström, a professor of historical osteology at Lund University who co-authored the new study. "The fetus may have been placed in the coffin after the funeral, when it was in a vaulted tomb in Lund Cathedral and therefore accessible." That jibes with evidence that the wrapped fetus had been hastily placed in the coffin. And other coffins in the same vault also held remains of several children. But it would take ancient DNA analysis to definitively rule out the possibility that the fetus was related to Winstrup—so that's what Ahlström and his colleagues set out to do.

The Lund researchers took DNA samples from Winstrup's right femur and the left femur of the fetus. They determined that the stillborn fetus was male and that there was a second-degree kinship with Winstrup, meaning that they shared about 25 percent of the same genes. There was a Y-chromosome match but the mitochondrial DNA was different, indicating the connection was on the paternal side of the family tree. The second-degree relationship could have been grandparent-grandchild, uncle-nephew, or even half siblings or double cousins.

To narrow the possibilities, Ahlström et al. turned to a close examination of the Winstrup family's genealogy. According to the genealogical records maintained at the House of Nobility in Stockholm, Sweden, the bishop was one of six children (four daughters and two sons). Since the Lund researchers were only concerned with paternal lineage, they could ignore the four sisters in their analysis. Winstrup's brother, Elias, died in 1633 at the age of 27, unmarried and childless. This enabled the Lund team to rule out certain possibilities: uncle/nephew, half siblings, and double cousins, specifically.

Bishop Peder Winstrup in turn fathered five children with his first wife, Anne Marie Ernstatter Baden, three of whom (two daughters and a son) survived to adulthood. He had no children with his second wife, Dorothea von Andersen.

So the most likely possible relationship, the authors concluded, was that Winstrup was the stillborn child's grandfather—i.e., the issue of his son, Peder Pedersen Winstrup, who bucked the family theological tradition to focus on military matters (particularly fortification), lost the family estate in the Great Reduction, and died destitute. However, there is a small likelihood that the fetus may have been that of the bishop's sister Anna Maria (who may have died in childbirth) and her husband Casper von Böhnen, assuming Casper belonged to a similar Y haplogroup.

As for how the fetus came to rest with the bishop, "It seems probable that the relatives would have had access to the crypt where the coffins of the Winstrups were stored, and, thus, a possibility to deposit the fetus in one of the coffins, in this case that of Peter Winstrup," the authors concluded.

DOI: Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 2021. 10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102939 (About DOIs).

reader comments

33