You might not want to sit down here,” Douglas Tinker said wearily, holding a glass of white wine. “Man, I haven’t won a case in so long.” The rotund balding man with the expansive white beard who recalled both Santa Claus and Ernest Hemingway was slouched in a booth at Buster’s Drinkery, an anonymous dive frequented by the lawyers who work nearby at the Harris County courthouse. It was a Monday afternoon in late October. While the boys at the next table were engrossed in their usual game of gin rummy, a loud party was going on in the streets outside, with honking horns, blaring music, and cheering crowds filling the sidewalks. Most of the several hundred revelers were Hispanic—Mexican American Texans to be precise—and they had plenty to celebrate. Yolanda Saldivar had just been found guilty of murdering their heroine, Selena. Tinker and his court-appointed co-counsel, Arnold Garcia, a hard-boiled former prosecutor from Jim Wells County, had just finished the thankless task of defending Selena’s killer, and they were already second-guessing their defense strategy. Believing they had discredited key prosecution witnesses, they had decided not to ask that the jury consider a lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter, which might have meant a shorter sentence. They had rested their case without calling Abraham Quintanilla, Jr., Selena’s father, whom they had portrayed as a controlling stage dad and manager and the catalyst behind the murder. They had decided against putting their client on the stand.

The honking of the horns grew more persistent. Tinker had had clients accused of unsavory crimes in his thirty years as a Corpus Christi defense attorney, including George B. Parr (the Duke of Duval County) and a Branch Davidian, but no client had generated the pure hatred that Saldivar did. There had been death threats, and more than once he had spoken of going out in a blaze of bullets, like Marlon Brando in Viva Zapata! “They saw us walk in. They know we’re here,” Tinker said in a low voice. “Let’s have another round.” When the evening news came on the television in Buster’s, it touted coverage of the “Selena trial.” Tinker talked back to the tube: “The Selena trial? What about the Yolanda Saldivar trial?” As the celebration outside continued, Tinker smiled at Garcia and raised his glass. “Well,” he said, “at least this reduces our chances of getting shot.”

The same could not be said for Yolanda Saldivar. Ever since that drizzly day in March when she shot Selena, she had been a marked woman. With millions of fans still distraught over Selena’s murder, it is debatable whether the 35-year-old Saldivar is safer in prison or out.

In life, the 23-year-old Selena Quintanilla Perez was the undisputed queen of Tejano music and an international superstar. In death, she has become bigger than ever. Since the shooting, the legend of the talented, beautiful, smart, clean-living vocalist who proved you can assimilate and have your culture too has spread from her hometown of Corpus Christi throughout the world. Street murals in barrios around the state have elevated her to a saintlike status almost equal to that of the Virgin of Guadalupe. More than six hundred babies born in Texas between April and September have been named Selena. Her posthumous album, Dreaming of You, debuted at number one on Billboard magazine’s album chart in July, making it the second fastest-selling release by a female singer in the history of popular music, after Janet Jackson. Selena’s appeal has always been strongest in South Texas, where she lived and worked, and for this reason, state district judge Mike Westergren moved the trial from Corpus Christi to Houston, where finding a fair jury would be easier.

Throughout the trial of State of Texas v. Yolanda Saldivar, Nueces County district attorney Carlos Valdez kept saying, “This is a simple murder case.” The evidence seemed to support him. Immediately following the shooting at the Days Inn Hotel in Corpus Christi on March 31, 1995, Saldivar, the former president of Selena’s fan club and close business associate, sat in a pickup in the motel’s parking lot for nine and a half hours with the murder weapon pointed at her head, negotiating her surrender to the police. After she gave up, she signed a confession admitting her guilt. This was an open and shut case, one that Valdez, a native of Molina, the same humble neighborhood on the southwestern edge of Corpus Christi where Selena had grown up and resided, was determined to win.

In his opening statement Douglas Tinker presented a much darker picture of the events surrounding the murder. Saldivar was Selena’s best friend, and she was trusted by the entire Quintanilla family; with, among other evidence, the audio tapes of her negotiations with the police, the defense would prove the shooting was an accident. Also, it would show that the confession she had signed didn’t include her claim that the shooting was an accident. Paul Rivera, one of the Corpus police officers who had interrogated her, had left that part out. Texas Ranger Robert Garza would reluctantly testify that he had witnessed Saldivar protesting to Rivera that the written confession he had prepared said nothing about the shooting being an accident. Furthermore, the defense would prove that Saldivar was forced into this confrontation and its unfortunate conclusion by Selena’s father, who lived his life through his daughter and was involved in a power struggle with Saldivar, even telling Selena that Saldivar was a lesbian. The defense believed that Abraham did not approve of Selena’s expanding her fashion business, with which Saldivar was intimately involved, into Mexico. (Selena had had a salon-boutique in San Antonio and another in Corpus Christi.) Her father, the defense said, thought she was doing so at the expense of the family band.

But once the trial got under way, Valdez preempted the defense’s blame-the-father strategy by calling Abraham as the first witness. Quintanilla obliged by speaking affectionately about the family and the band he managed and promoted. He forcefully denied ever threatening Saldivar, calling her a lesbian, or raping her, as she claimed on the hostage audio tapes. (His initial response to prosecutors when informed of the rape accusation had been “Have you ever seen the woman?”) The surprise of the trial was Tinker’s decision not to cross-examine Quintanilla or recall him later. It meant the defense was not going to pursue the sordid details it had alleged. “He suffered through this,” Tinker said after the verdict was announced, explaining what seemed to be an about-face. “He and his family are hurt by what happened, and I decided not to put him through it.” Cross-examining Abraham, the defense had concluded, was too risky: It might backfire and stir up sympathy for him. Therefore, the defense stuck to the evidence concerning the accidental-shooting claim and the incomplete confession.

The jury didn’t buy any of it. But before and after the verdict and the life-in-prison sentence were handed down, there was much drama at the Harris County courthouse, involving the aggressive lawyers, the grieving families, the eyewitnesses, and the Selena faithful. Over the course of the fourteen-day trial, which was the most closely watched murder trial in Texas in years, one thing was certain: Selena’s ghost hung over the courtroom and the hundreds of fans keeping vigil outside.

The Testimony

Eyewitness testimony by family members, boutique employees, gun shop employees, and hospital nurses filled in some blanks about the events leading up to March 31. One revelation was Saldivar’s ambivalence about the murder weapon. She bought the Taurus 85 .38-caliber double-action revolver on March 11 at A Place to Shoot in San Antonio, telling the clerk she was an in-home nurse who was getting death threats from family members of a terminally ill patient she cared for. Two days later, on March 13, the same day she had her lawyer, Richard Garza, draw up a resignation letter to Selena, Saldivar picked up the gun. She returned it on March 15, saying her father had given her a .22 and she no longer needed the Taurus. On March 26 she returned to repurchase the gun.

Part of Saldivar’s indecisiveness about the gun seemed to be a result of her uncertain employment status throughout March. According to the testimony of Christ Perez, Selena’s husband, Selena told Saldivar over the telephone that she was fired on March 10, the day after Abraham, Selena, and her sister, Suzette, had confronted Saldivar claiming to have discovered evidence that she had stolen up to $30,000 from the fan club. But both Suzette and Celia Soliz, one of Selena’s boutique employees, testified that Selena had not made a final decision until March 30, the day before the shooting. Perez also testified that Saldivar was to continue working with Selena only to help set up the fashion ventures in Mexico and that Saldivar had bank records Selena wanted back.

There was also some gripping testimony about Selena and Saldivar’s visit to Doctors Regional Medical Center the morning of the shooting. Saldivar had said that she had been raped earlier that week in Mexico, but after a medical examination proved inconclusive, Selena realized Saldivar was lying, according to two nurses at the hospital. The murder took place less than half an hour after the two left the hospital. Perhaps a fatal mistake was made in dragging out Saldivar’s firing. Having most of the month of March to contemplate that her relationship was over with the person she described as “the only friend I ever had” was too much for Saldivar to take. As she told hostage negotiator Larry Young, “I had a problem with her and I just got to end it.”

The Defense

If Douglas Tinker wasn’t exactly a one-man dream team, the 61-year-old attorney had a long record of impressive acquittals. The criminal justice section of the State Bar of Texas had recognized him as the state’s outstanding criminal defense lawyer for 1995. After Judge Westergren appointed Tinker to defend Yolanda Saldivar, Richard “Racehorse” Haynes said that she had lucked into $50 million worth of representation. At Tinker’s request, Westergren appointed Arnold Garcia to assist him because Garcia spoke Spanish, as did Saldivar, and was a tireless investigator. Before the trial, many Houston lawyers had offered to assist Tinker in the high-profile case. Tinker took on Fred Hagans, a personal-injury attorney and a former partner of superlitigator John O’Quinn. This was Hagans’ first criminal case, and he invested considerable sums of money for the experience. He offered the services of his co-counsel Patricia Saum, hired jury consultant Robert Gordon, and staged a mock trial at an expense of more than $20,000. It was during the mock trial, with cameras filming the reactions of every “juror,” that Tinker first sensed his case might not be as strong as he had thought. Though one third of the “jury” voted to acquit, not one of the test jurors seemed bothered by the actions of Paul Rivera, the officer who took Saldivar’s confession but didn’t include her claim that the shooting was accidental. If the real jury didn’t buy the bad-cop theory, would they buy the accident?

The Prosecution

Carlos Valdez had never tried a felony case before he was elected district attorney for the 105th Judicial District two years ago. His presentations and examinations in court left room for improvement, but the boyish 41-year-old DA had the evidence and he knew how to delegate. Valdez’s chief prosecutor, Mark Skurka, a garrulous 36-year-old, tried the bulk of the case and ably demonstrated why he has prosecuted more murder cases in Nueces County than anyone else. During closing arguments in both the verdict and the sentencing phases, Skurka posted a picture of Selena in the jury box and repeatedly spoke to it, especially when he was referring to the defense’s claim that the shooting was accidental, which he labeled “hogwash.” He called the defense strategy the “squid defense,” attacking Saldivar’s defenders for putting out a black cloud of inky doubt to get away from the essence of the case. Elissa Sterling became part of the team when the case was assigned to Westergren’s 214th District Court, where Sterling prosecutes cases. Between the three of them, the prosecution got the desired verdict by sticking to the indisputable evidence, by calling both friendly and hostile witnesses before the defense could, and by keeping the jurors focused on the victim: Selena’s screams and her last steps and words immediately following the shooting were recounted by five motel employees, one of whom, Norma Martinez, said she had heard Saldivar shout, “Bitch!” at Selena. Their testimony, more than anything else, convicted Saldivar.

The Jury

It took two days to select the twelve-person jury. Judge Westergren had decided that to keep things moving, he wouldn’t seat alternates or sequester the jurors. Throughout the trial, the jury paid close attention, took notes, and showed little emotion, except for one blond Anglo female, who cried at the sight of the autopsy photographs and during the teary testimony of Frank Saldivar, the father of the accused. Up until the verdict, Tinker kept saying how much he liked this jury, in particular the three Anglo men sitting on the back row, one of whom was an ex-Marine. Tinker liked them so much he thought he could make his case without getting into the seamier aspects of the alleged split between Selena and her father. He liked them so much he called only three witnesses for the defense and recalled only two prosecution witnesses before resting, without asking the judge to consider a lesser charge. The guilty verdict was returned in less than three hours. The sentence of life in prison took nine hours. Charles Arnold, who was one of the jurors Tinker liked so much, had held out for a forty-year sentence before giving in.

The Judge

The bow-tied Mike Westergren was the anti-Ito, the kind of judge who would have kept O.J. Simpson’s dream team on a short leash. If nothing else, the unsuccessful candidate for the state Supreme court was going to make the trial run on time and not let it get out of hand. Despite pretrial petitions from the Univision and Court TV networks, the 48-year-old judge ruled that cameras would not be allowed in his court.

He showed a less serious side after the jury began deliberating punishment, when he visited with spectators in the gallery. As everyone began to relax, the din grew so loud that a bailiff had to shout, “Quiet in the courtroom!” Westergren, talking and laughing with two young lawyers, had sheepishly raised his hand and said, “I’m afraid it was me.”

Yolanda

Seeing the accused up close, it was hard to imagine that the tiny four-foot-nine woman could hurt a flea, much less pull the trigger of a murder weapon. Whenever a witness was asked to identify her, she stood up and tossed her head back with an air of pride. But when the five hours of hostage-negotiation tapes were played in the court—a grueling listening experience, the eerie sound of her sobs and hysterical moans filling the room—Saldivar quietly began crying along with the tapes. It was a sad sight, but it humanized the cold-blooded murderer that the prosecution had portrayed. She broke down sobbing after the verdict was read, quietly saying she wanted to kill herself, while defense investigator Tina Valenzuela comforted her.

Where’s Larry?

The most potentially explosive evidence was the recordings of conversations between Saldivar, sitting in the motel parking lot with a gun to her head, and the Corpus Christi Police Department’s hostage negotiation team. Lead investigator Paul Rivera testified that he had been aware of the tapes in April. But they didn’t surface until late August, after Tinker called police chief Henry Garrett and asked for them. Played in their entirety, they depicted Saldivar as distraught and panicky. Between her wails, Saldivar said over and over, “I didn’t mean to do it,” suggesting the shooting was an accident. She also blamed Abraham, saying, “He made me do it. He was out to get me…This man was so evil to me. My father even warned me about him. My father said I should get out before I get trapped.”

The special two-way phone line used by the hostage negotiation team was a flawed piece of technology. A portable phone would have allowed Saldivar a conference call with her mother in San Antonio, which she had asked for from the start. The two-way phone picked up the broadcast signal from the KSIX-AM transmitter, located one hundred yards from the motel parking lot, which is why the voice of Milo Hamilton calling a Rangers-Astros exhibition baseball game and the melody of “The Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless)” could be heard when the tapes were played in court. It was through this interference that Yolanda heard a news report that Selena was dead, at which point she became even more hysterical. The tapes also reveal that hostage negotiators promised Saldivar that her mother and her lawyer, Richard Garza, would be waiting for her when she gave up. She wasn’t and he wasn’t. One thirty-minute tape consisted of little else but Yolanda repeating the mantra “Where’s Larry?”—an appeal to bring negotiator Larry Young back on the line. The mantra was accompanied by a mysterious and extremely irritating electronic buzz. The bizarre audio conflagration inspired “Where’s Larry?” T-shirts, which were hawked on the street the next day.

The Families

Both the Quintanilla and the Saldivar families came from humble Mexican-American roots and had survived and flourished by sticking close to their kin. The Quintanillas lived in three adjacent homes on Bloomington Street in the Molina neighborhood of Corpus Christi, the Saldivars in four houses and a trailer on five acres just beyond the southern city limits of San Antonio. While the Quintanillas showed signs of wealth—they wore expensive clothes and brought along their own family spokesman and publicist—the Saldivars were a true blue-collar family.

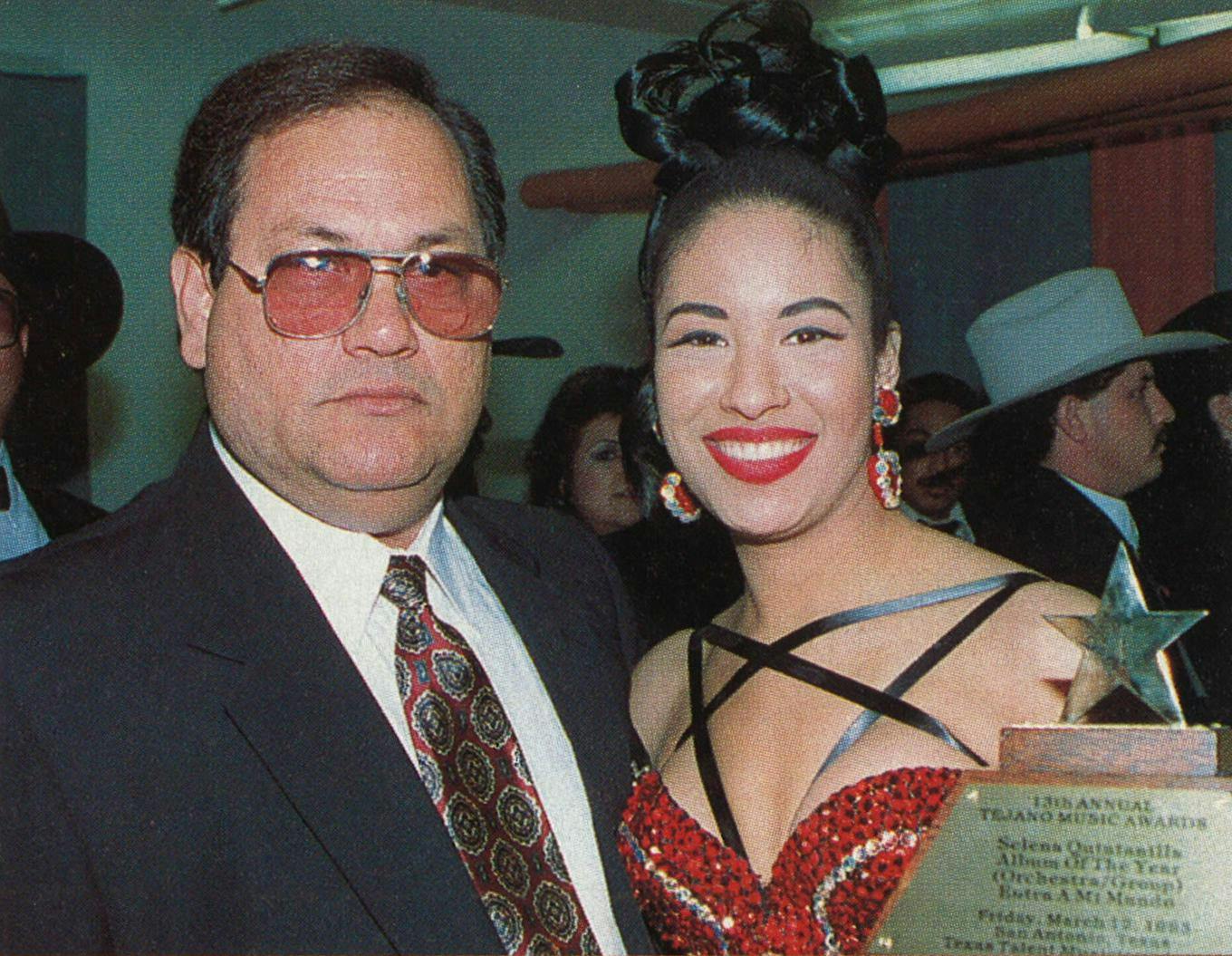

The 56-year-old Abraham Quintanilla, a forceful presence, was a dominant figure at the trial not only because the defense portrayed him as the one who drove Yolanda to buy the murder weapon but also because he was Selena’s father and her business manager. On many occasions since the shooting he had shown himself to be a tough business manager, cutting deals and maximizing profit from all things Selena. He held countless press conferences to announce, among other things, the creation of the Selena Foundation; to introduce his new discovery, twelve-year-old Jennifer Peña, who resembles a young Selena; and to reveal his role as executive producer of the movie being made about Selena’s life, which filmmaker Gregory Nava was writing from the father’s perspective.

He became increasingly hostile to the media, though, after the value of Selena’s estate was published in the San Antonio Express-News in September. Probate court documents revealed that her net worth was only $164,000 and that Chris Perez had given up his right to administrate the estate to Abraham.

At the trial, Perez appeared thoroughly devastated by the loss of his wife, though the handsome, ponytailed 26-year-old is a delicate figure by nature. Before the trial, he said that he wanted to continue playing guitar, focusing on rock music. He also answered critics who questioned the handling of the estate, saying, “I didn’t have a lawyer just like Selena didn’t have a lawyer. We didn’t need a lawyer because this is family. And why should I worry about losing something? I have already lost what I always wanted. I would trade everything I had if I could have her back.”

Marcella Quintanilla, Selena’s attractive mother, had said little publicly following the shooting in March. She was having just as much trouble as Perez coping with her daughter’s death. When motel maintenance worker Trinidad Espinoza began recounting Selena’s last moments, Marcella was overcome and had to leave. The next day, she was admitted to the coronary unit of St. Joseph’s Hospital for overnight observation.

Yolanda’s mother, Juanita, was the only Saldivar to attend the entire trial, usually accompanied by one of her six other children and various nieces and nephews. Gray-haired and wrapped in a sweater, she was the living embodiment of the pobrecita abuelita, the “poor little grandmother.” On several occasions, she too had to be escorted out of the courtroom, overwhelmed with emotion. Yolanda’s father, the diminutive Frank Saldivar, had recently retired after forty years of balancing enchilada plates and glasses of iced tea as the headwaiter at Jacala Restaurant in San Antonio. He spent his sixty-ninth birthday on the stand, fighting back tears and imploring jurors to have mercy on “our baby girl.” After sentencing, Juanita and Frank crossed the rail and hugged and kissed Yolanda good-bye.

The Street

Every day, Selena fans gathered outside the courthouse and made their feelings known by holding signs, wearing shirts, or shouting chants such as “Ju-sti-ci-a!” or “Cien años!” As the trial neared conclusion, their numbers swelled and the mood took on a vindictive streak, evidenced by a “Hang the Witch” placard, posters that depicted Saldivar in handcuffs standing in the middle of a target with the words “la marrana” (“the sow”) written underneath, and a “Kill Yolanda” message painted in white shoe polish on the windshield of a Toyota. But imagination was at work too. One sign paraphrased a line from the new crossover country hit of Selena’s old labelmate and duet partner Emilio Navaira: “There Can Never Be Enough Justice for Selena, But It’s a Damn Good Start.”

The celebrations around the courthouse following the guilty verdict and the sentence were marked by the strange sight of tears on the faces of many fans, especially older women. For them, Selena had already evolved from a pop star into an icon of grief.

The Media

There were more than two hundred media credentials issued for the trial, with almost as many Spanish-language media as English-language media. The most thorough TV coverage came from the two Spanish-language networks, Univision and Telemundo, both of which aired at least ninety minutes’ worth of coverage daily. Univision’s Marie Celeste Arraras—the doe-eyed, henna-haired anchor of “Primer Impacto,” a news program seen throughout the United States and in fifteen foreign countries—was the trial’s undisputed media star, judging from the fans’ wolf whistles and the way they crowded her on the street. Her program had the most knowledgeable courtroom analyst, former Corpus state district judge Jorge Rangel, who knew Texas law and the players in the trial.

The O.J. Effect

As murder trials go, the one in Houston had little to do with the O.J. Simpson trial in Los Angeles other than it involved homicide and a celebrity. Nevertheless, comparisons were frequently made. Before the trial, Abraham Quintanilla observed that after the O.J. verdict anything was possible. Once the trial began, the fear spread through barrios in Texas that Saldivar might get off as a result of police officer Paul Rivera’s questionable handling of the confession. Selena’s own Mark Fuhrman was going to mess everything up.

The verdict shored up trust in a legal system that has come under increasingly close and critical scrutiny. It proved to Texas’ largest minority group that the criminal justice system, flawed as it may be, really does work. Following the trial, the League of United Latin American Citizens announced a campaign to urge Hispanics to seek jury duty.

Waiting for the Jury

While the jury deliberated the sentence, the mood in the courtroom turned informal and almost jovial. Sheriff’s deputies ceased patting down media when they reentered the courtroom. A bailiff approached Yolanda Saldivar and whipped out a court pass, asking her to sign it. Pretty soon, members of the press were slipping their passes to Arnold Garcia for Saldivar to sign. Westergren and Valdez were signing autographs too. The Saldivar family sought out the autographs of several reporters. Tinker posed for sketch artists and quipped, “If the jury never comes back, it would be fine with me.” Two spectators dozed off. So, briefly, did Abraham Quintanilla, sitting alone in the family-seating section. This was hardly the stuff of a trial of the century.

When the sentence of life in prison was returned, Carlos Valdez saluted the jury. Douglas Tinker announced that he would appeal. Following the final press conference, the same man who was fretting about being followed by angry Selena fans was still being hounded. But the fans didn’t want Tinker’s head. They wanted his autograph.

The Future

In addition to the Selena movie, her band’s farewell tour next spring, and other Selena memorial projects, Abraham Quintanilla has been building a roster of young talent for his custom label distributed by Capitol EMI. A 900 number has been set up for fans to telephone condolences to the family for $3.99 per call. Selena’s sister, Suzette, handles the boutiques and Selena merchandising. Selena’s brother, A.B. Quintanilla III, has been busy producing acts in the recording studio and writing. His composition “Estúpido Romántico,” co-written with former Selena backup singer and popular solo act Pete Astudillo, was a big hit for the Tejano supergroup Mazz, and he recently composed a theme song for a Mexican soap opera. He has just moved his wife, Vangie, and their two children to a palatial new home west of Corpus. Chris Perez is looking for a new place too. The three Quintanilla homes on Bloomington Street will soon be an empty nest.

Family Matters

Back inside the friendly dimly lit confines of Buster’s Drinkery—two hours after the jury had returned its verdict—the conversation shifted from law to family. Tinker had spent the previous weekend camping out in the woods of Alabama. “My son attends boarding school there and it was parents’ weekend. I hadn’t seen him in several months,” he said. Garcia spoke lovingly of his son, Javier, a metal sculptor. They agreed that no matter how hard you try, you can never tell how your kids will turn out. Abraham and Marcella Quintanilla loved their daughter and had tried to protect her; Frank and Juanita Saldivar loved their daughter, too. And they all wound up in a court of law in Houston, where twelve strangers passed judgment on why everything turned out so badly.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Crime

- Selena

- Corpus Christi