YAKIMA, Wash. -- In a quiet hillside enclave high above the everyday commotion of central Los Angeles, a house priced at $1.595 million still features architectural details beloved by its first owner.

From the long living room with its large fireplace, silent film star Barbara La Marr could admire the view through a set of tall leaded French doors. She could cross a small bridge linking her Whitley Heights home with a detached studio, or stroll its lush grounds sheltered by dense hedges.

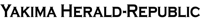

Bought with her earnings as a screenwriter and an actress, the 1921 Mediterranean-style structure was the first real home for the dark-eyed, black-haired beauty after growing up as the daughter of restless parents who moved almost every year.

Born in Yakima on July 28, 1896, as Reatha Dale Watson, her time in her hometown was brief, and there are almost no references to her. The Yakima Valley Museum highlights La Marr as part of an exhibit on notables from the area, but the hospital where she may have been born is long gone.

Dubbed the “world’s wickedest vamp” by one fan magazine, La Marr seemed steeped in drama for much of her life, which Sherri Snyder details in her book, “Barbara La Marr: The Girl Who Was Too Beautiful for Hollywood,” published in November by the University Press of Kentucky.

“She really was one of a kind. 'We shan’t see her like again',” said Snyder, quoting a journalist friend of La Marr's. Snyder has worked since 2007 to research and record La Marr’s life story as a writer and actress.

“Her press agent said that 'everything she did was colored with news value' ... She kept him on his toes."

Newspapers got a taste of the sensational stories to come when La Marr was reportedly kidnapped at age 16 by her older half-sister and a male companion. A year later, her behavior at Los Angeles nightclubs prompted law enforcement to declare her “too beautiful” to be on her own and authorities ordered her to leave the city.

She couldn’t stay away, though, returning after a short time and establishing herself as a silent film writer and star who performed with such notables as Douglas Fairbanks, Ramon Novarro, Lon Chaney and David Butler. La Marr appeared in 26 films in five years as the drama continued in her personal life with numerous scandals, failed marriages and a hidden pregnancy.

La Marr took lovers like roses — “by the dozen,” she liked to say.

But did she, really? Outrageous stories about celebrities, sometimes created by the celebrities themselves, helped sell tickets and at times La Marr embellished or completely ignored the truth, making research even trickier for Snyder.

“That was the trend back then,” she said. “In those days the public did not distinguish between the flesh and blood (person) and luminous counterpart. They wanted their stars larger than life.”

All fabrication aside, La Marr’s tempestuous life of distracting beauty and sensational stardom, enthusiastic partying and crash diets and utter disregard for sleep, was still the stuff of Hollywood legend. After collapsing on a movie set, she died in Altadena, Calif., of pulmonary tuberculosis and nephritis on Jan. 30, 1926.

“She squeezed a lot of living into her 29 years,” Snyder said.

‘She never gave up’

William and Rose Contner Watson moved to Yakima after William weathered some scandal of his own when the newspaper he ran with his brother Benjamin, the Sunday Mercury in Portland, was indicted by a U.S. grand jury in 1891 for sending “obscene papers” through the mail, Snyder’s book notes.

The Watsons left for Yakima, arriving in August 1893. William first worked as editor of the Yakima Herald before getting a job at the Yakima Daily Times. He supplemented his income as the Yakima Commercial Club’s publicity agent in 1894, Snyder’s book notes.

His daughter Reatha was born late in the evening at a Yakima maternity home, she wrote.

Children were usually born at home then. Though the book doesn’t say what or where the maternity home was, it is possible that Reatha was born at St. Elizabeth Hospital, then in its second location at the corner of Fourth and E streets.

Rose was nearly 40, so potential health complications may have prompted her to have her daughter at a medical facility, Snyder surmised.

As any researcher knows, gaps in knowledge often occur no matter how diligent the effort, resulting from lost or destroyed records, poor record-keeping or haphazard storage of information. When Reatha was born in 1896, Yakima was still called North Yakima and was only 10 years old, having incorporated in 1886 after its rancorous split and relocation from today’s Union Gap.

“She had a half-brother and a half-sister” from her mother’s previous marriage, Snyder noted. Reatha also had a full brother, William Jr.

“There might have been another half-brother in there somewhere,” she added. “It’s hard to say. Her half-brother went to prison in the late ’20s. He went to jail for incest. He said he had two brothers.

“Her mother, in two census reports, she listed five children. I couldn’t find any records backing that up,” Snyder said. “I put in the book (that) it’s a possibility. I don’t say she had a second half-brother, but it’s indicated by this.”

Only two years after Reatha’s birth, the Watson family had moved back to Portland.

“He would go to some city or small town, start a paper, boom it, and then sell it,” La Marr was quoted as saying in Snyder’s book.

Snyder’s is the first full-length biography of La Marr. An actress who lives in Los Angeles, Snyder also created a web site, www.barbaralamarr.net, which she updates often.

“What inspires me most about her is her underlying strength. That’s why I fell in love with her story,” Snyder said of La Marr. “Her life has many sorrowful elements — she had her demons — but what absolutely inspires me is her underlying strength. She never gave up, even to the end. She never stopped endeavoring to achieve her goals.

“She somehow managed to rise through the tragedy she experienced. But she never gave up. It amazes me that she achieved career success when so many women lived lives of domesticity.”

Channeling a legend

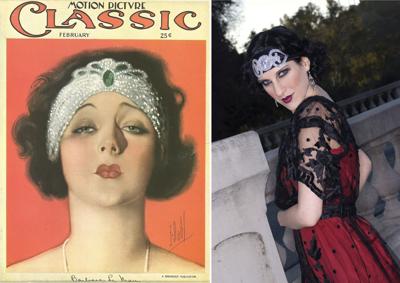

Snyder’s acting background is in theater. That’s how she first learned of La Marr in 2007.

“The Pasadena (Playhouse) was looking for an actress to play Barbara La Marr for a production called ‘Channeling Hollywood.’ It spotlighted five notables connected to Pasadena,” Snyder said.

“Barbara died in Altadena (but) they decided to include her (though) she’s not connected to Pasadena. ... They were looking for actors and actresses to not only play their respective roles but also research (them) and (write them) in monologue form.”

She had never heard of La Marr. That’s common.

“One of the main reasons is because many of her films have not survived. There are a few out there. Some of her most popular films survived,” Snyder said.

Turner Classic Movies recently showed one of her more popular movies, “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1922). Another well-known film, “The Three Musketeers” (1921) starring Fairbanks, is available on Amazon Prime Video, and fans can watch another Fairbanks feature, “The Nut” (1921), on YouTube.

Not many silent films have survived. Some were destroyed by the studios that created them when talking pictures replaced silent films, Snyder said. “In other cases, the film was filmed on unstable film stock. Now and again, more films are being discovered.”

Her portrayal of La Marr resulted in a fateful meeting with La Marr’s only child, Don Gallery, that led to the book. Gallery was 3 when his mother died and he was adopted by her friends, ZaSu Pitts and husband Tom Gallery.

“Barbara’s son was living in Puerto Vallerta with his wife and came up to see the play. He was very moved by it. He said he felt his mother in my performance,” Snyder said. “I noticed toward the end he was wiping tears from his eyes.

“He said, ‘I finally met the person who is supposed to write the book.’”

A few days after her performance, Don Gallery asked Snyder to write his mother’s biography.

“I’d fallen in love with her story so much that I couldn’t say no,” Snyder said. “I spent the next 10 years researching and writing her biography.

“Some told me in 2007 that I should turn my 'Channeling Hollywood' performance into a one-person show; I did. I perform it at least once a year. I performed it at (Grauman’s) Egyptian Theatre and Hollywood Forever” Cemetery, where La Marr is buried with her parents. “It’s a lot of fun,” Snyder added.

Becoming Barbara La Marr

Reatha made her acting debut in Tacoma in 1905, dressed as a waif and reciting a poem, “Nobody’s Child,” in an amateur showcase held by the Allen Stock Company.

Her career gained traction as she performed on bigger stages in bigger cities. From Tacoma she went to Spokane, where she joined The Shirley Company in 1907, then took various small roles with a Seattle-based theater company either in 1907 (when her father was working again in Yakima) or possibly around early 1912, according to Snyder’s book.

William had relocated his family from Yakima to Hanford in 1908 and the family eventually settled in Southern California.

Reatha’s first successful movie audition at age 14 proved bittersweet when she was dismissed from the set. After her scandalous “kidnapping” (the 16-year-old may have gone willingly with her older half-sister and male companion) and wild nightclub antics that prompted authorities to order her from the city, she returned to Los Angeles, living with friends and marrying for the first time at age 17.

It turned out her first bridegroom was already married with two young sons, bringing more scandal. And her movie career hadn’t even started yet.

“Her whole life astounded me as I went through the old newspapers (with stories of) the kidnapping, the bigamist marriage,” Snyder said.

Reatha met dancer Robert Carville on the cusp of 1915. She had dyed her hair blonde and told him she wanted to perform with him. She also wanted a new name, Snyder wrote. He suggested Barbara, after his grandmother, and La Marr, after elderly Southern neighbors he remembered from his childhood.

After two years of dramatic highs and lows working with Carville as a dancer in cabarets throughout the country and on Broadway, and as a vaudevillian in headlining comedy routines, La Marr moved to Los Angeles for good. There, she became a screenwriter in 1920, then an actress.

From that point on, famous and infamous people flitted into and out of La Marr’s life as versions of her “true story” appeared in fan magazines and newspapers.

Among her closest friends was Paul Bern, the film director, screenwriter and producer for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer who was briefly married to Jean Harlow before his mysterious death in September 1932. When La Marr died six years earlier, Bern left roses on her crypt and had her likeness carved on a beam of his home.

La Marr received a posthumous star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. She rests with the ashes of her parents in crypt No. 1308 of Hollywood Forever’s Cathedral Mausoleum.

“They’re not listed on the front. You wouldn’t know they are there,” Snyder noted of La Marr’s parents. “Her brother brought them there after her father passed. Her father passed after their mother.”

Snyder admires La Marr as a trailblazer.

“She looked to no one but herself to determine her place in the world,” she said. “She wanted to live her life her way — that’s what I admire the most.

“... Her life has many sorrowful elements — she had her demons — but what absolutely inspires me is her underlying strength,” Snyder added. “She never gave up, even to the end. She never stopped endeavoring to achieve her goals.”

(0) comments

Comments are now closed on this article.

Comments can only be made on article within the first 3 days of publication.