SoftBank’s first bet in energy storage is a startup that stacks concrete blocks

SoftBank’s Vision Fund is investing $110 million in the Swiss startup Energy Vault, which stores energy in stacked concrete blocks. Quartz was the first to report on the startup when it came out of stealth mode last year.

Two things make this investment unprecedented. First, it’s an unusually large sum for a company that hasn’t even existed for two years or built a full-scale prototype. Second, by making an energy storage bet, the $100 billion SoftBank Vision Fund—which has invested in startups like Uber, Slack, WeWork, and Paytm—is signaling to the wider market that this area of technology is ripe for large investments.

So far, most investments in energy storage have gone to companies building lithium-ion batteries. They’re an attractive bet, because carmakers are willing to pay a premium for batteries that will help electric cars compete with their gas-powered cousins.

But the technology to store electricity doesn’t need to be as powerful as lithium-ion batteries. While companies like Tesla and Sonnen sell lithium-ion batteries for homes and, in larger packages, for the grid, Energy Vault’s bet is that its technology will prove to be cheaper. That’s because it uses low cost materials: cement and sand to make blocks, cranes to lift and drop the blocks, and reversible motors to convert electricity into potential energy and vice versa.

Energy Vault was founded in 2017, and it built its first energy-storage prototype in only nine months with less than $2 million. Now Akshay Naheta, a managing partner of SoftBank’s Vision Fund, believes the startup is ready for an injection of a large sum to deploy its technology around the world.

Fifth-grade physics

Here’s how that system works, as we explained previously:

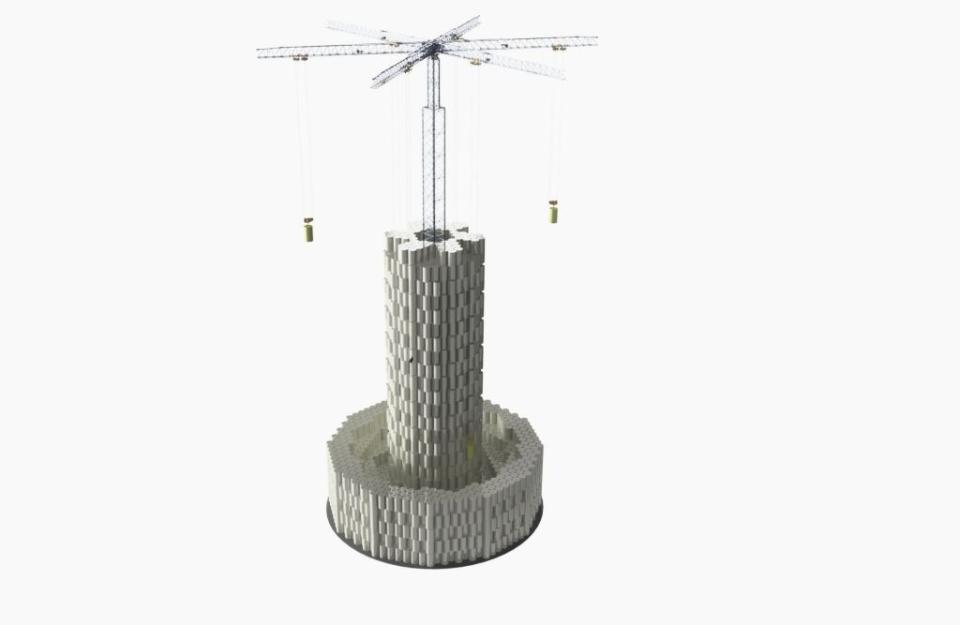

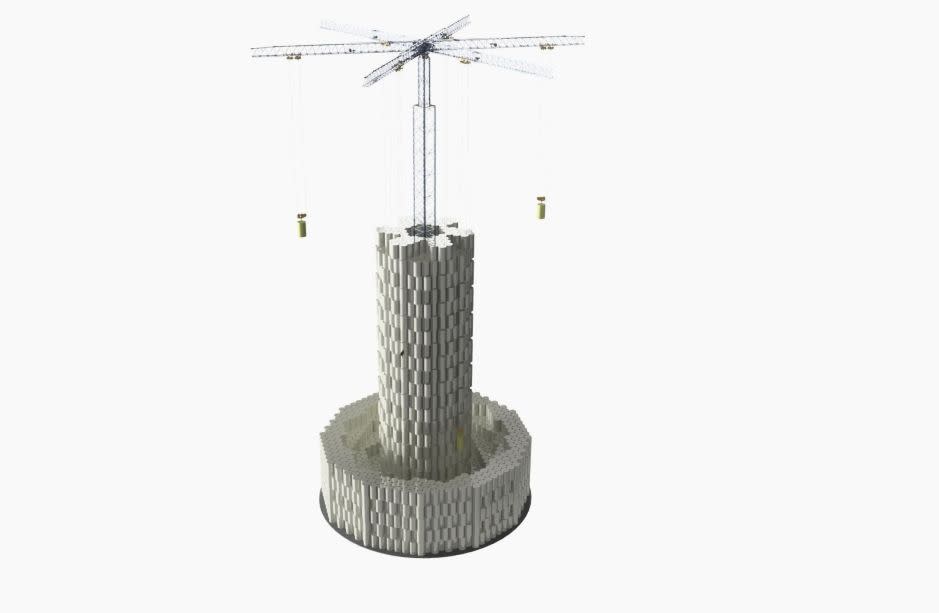

A 120-meter (nearly 400-foot) tall, six-armed crane stands in the middle. In the discharged state, concrete blocks weighing 35 metric tons each are neatly stacked around the crane far below the crane arms. When there is excess solar or wind power, a computer algorithm directs one or more crane arms to locate a concrete block, with the help of a camera attached to the crane arm’s trolley.

Once the crane arm locates and hooks onto a concrete block, a motor starts, powered by the excess electricity on the grid, and lifts the block off the ground. Wind could cause the block to move like a pendulum, but the crane’s trolley is programmed to counter the movement. As a result, it can smoothly lift the block, and then place it on top of another stack of blocks—higher up off the ground. The system is “fully charged” when the crane has created a tower of concrete blocks around it.

When the grid is running low, the motors spring back into action—except now, instead of consuming electricity, the motor is driven in reverse by the gravitational energy, and thus generates electricity.

Since it came out of stealth mode last year, revealing a one-tenth scale prototype in Biasca, Switzerland, the company has received plenty of interest from potential customers, says Rob Piconi, Energy Vault’s CEO. The SoftBank investment will help it first build a full-scale prototype—one each in Italy and India—and then build multiple towers—each with a capacity of 35 MWh—for actual customers soon after.

“We at the Vision Fund want to come in when a technology is proven and it’s ready to scale. That’s what’s so exciting about this technology. It’s not a science problem. It’s fifth-grade physics,” said Naheta. “There will be teething problems with any new technology. But this is more of a scaling problem.”

Simulation of a large-scale Energy Vault plant.

Bring on the unicorns

Energy storage companies rarely raise so much money. Two Silicon Valley-based companies building next-generation lithium-ion batteries, Sila Nano and QuantumScape raised $170 million and $100 million, respectively, in the last year. But the companies have had time to build up to those significant rounds—both were founded in 2011—and investors justified their large buy-ins on the basis that the batteries will command premium pricing in a world of premium electric cars. The companies are now unicorns, worth more than $1 billion.

That’s what makes Naheta’s energy-storage bet an unusual one. It’s not a bet on a technology that’ll command premium prices. If anything, the amount of electricity that needs to be squirreled away requires the technology to be cheap.

To understand why the bet might be a smart one, let’s explore the grid-scale energy-storage industry a little more. As we previously explained:

Experts broadly categorize grid-scale energy storage into three groups, distinguished by the amount of energy storage needed and the cost of storing that energy.

First, expensive technologies, such as lithium-ion batteries, can be used to store a few hours worth of electricity—in the range of tens or hundreds of MWh. These could be charged during the day, using solar panels for example, and then discharged when the sun isn’t around. But lithium-ion batteries for the electric grid currently cost between $280 and $350 per kWh.

Cheaper technologies, such as flow batteries (which use high-energy liquid chemicals to hold energy) can be used to store weeks worth of energy—in the range of hundreds or thousands of MWh. This second category of energy storage could then be used, for instance, when there’s a lull in wind supply for a week or two.

Technologies for the third category doesn’t exist yet. In theory, yet-to-be-invented, extra-cheap technologies could store months’ worth of energy—in the range of tens or hundreds of thousands of MWh—which would be used to deal with interseasonal demand.

Ravi Manghani, head of energy storage at Wood Mackenzie, says the demand for the second category of energy-storage technologies is growing. That’s because in most places in the world, the costs of solar and wind power are now lower than new-build fossil-fuel power plants. These renewables are intermittent, creating demand for technologies that can cheaply store the energy for use when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

While lithium-ion battery prices are likely to fall below $100 per kWh eventually, they are unlikely to fall below $150 per kWh in the next decade. Piconi says that, when Energy Vault builds its tenth full scale plant, it will hit that price point—and that plant could be up and running within the next few years.

“Long-duration energy storage is now a hot area to invest,” Manghani said. “When that happens, venture capitalists want to make bets to find early success.” That’s the context in which Naheta’s bet starts to make sense.

Other investors, such as Bill Gates-led Breakthrough Energy Ventures, have invested in startups like Malta and Form Energy, which are promising to develop long-duration energy storage. But both companies are many years away from readying their technology for commercial deployment: Malta is looking to build a pilot-scale project and Form Energy is still in the lab-studies phase.

“Even though, on paper, this company is ‘early stage’ in every sense of the word, the technology works,” Naheta said. “We feel very confident with the diligence we’ve done. With our partnership, we can scale up it quickly.”

The next few months, however, will be crucial. Naheta admitted to the biggest known unknown: Energy Vault hasn’t yet built a full-scale plant. That should happen in the next few months, according to Piconi. Scaling up will bring challenges: How to access so much sand, gravel, or waste material to build hundreds of 35 metric ton blocks on the plant’s site? How to ensure that the tower remains stable in its fully charged state? How to operate in different weather conditions around the world? Once built, does it work just as predicted?

If it does, then Energy Vault’s chance of success are high. “The economics are such that purchase orders from creditworthy customers open up multiple avenues of financing beyond raising capital against equity,” Naheta said. “That’s why we said, ‘Look, if we miss this round, they might never, ever need a round again.’”

But what if it doesn’t work out? Will SoftBank take its money back? “We’re not novices in the business,” said Naheta laughingly. “We know the bet we’re making.”

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: