There are 5.4 million posts under the #acne hashtag on Instagram. Many are what you’d expect: “before” images of pimply faces matched with “after” images of glowing skin, paid endorsements of creams, and suggestions of which foods will make one healthy and beautiful. Pimples can and should be banished, the posts largely suggest. But one photo in the #acne stream that caught my eye is a little different. It’s an unretouched close-up of a girl with tiny flowers affixed to her eyelashes, cheekbone, and jawline, framing the pink acne scars peppering her cheek.

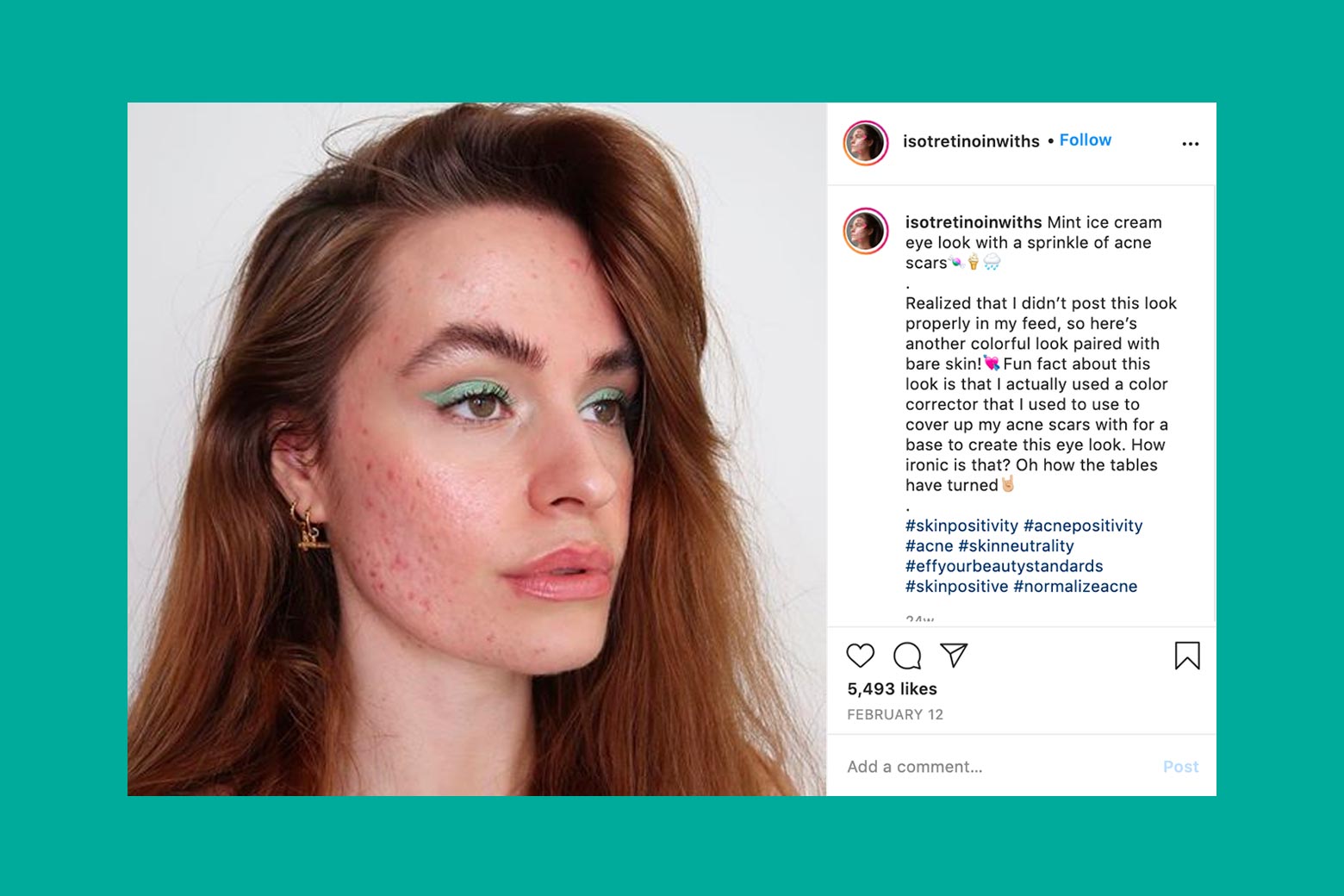

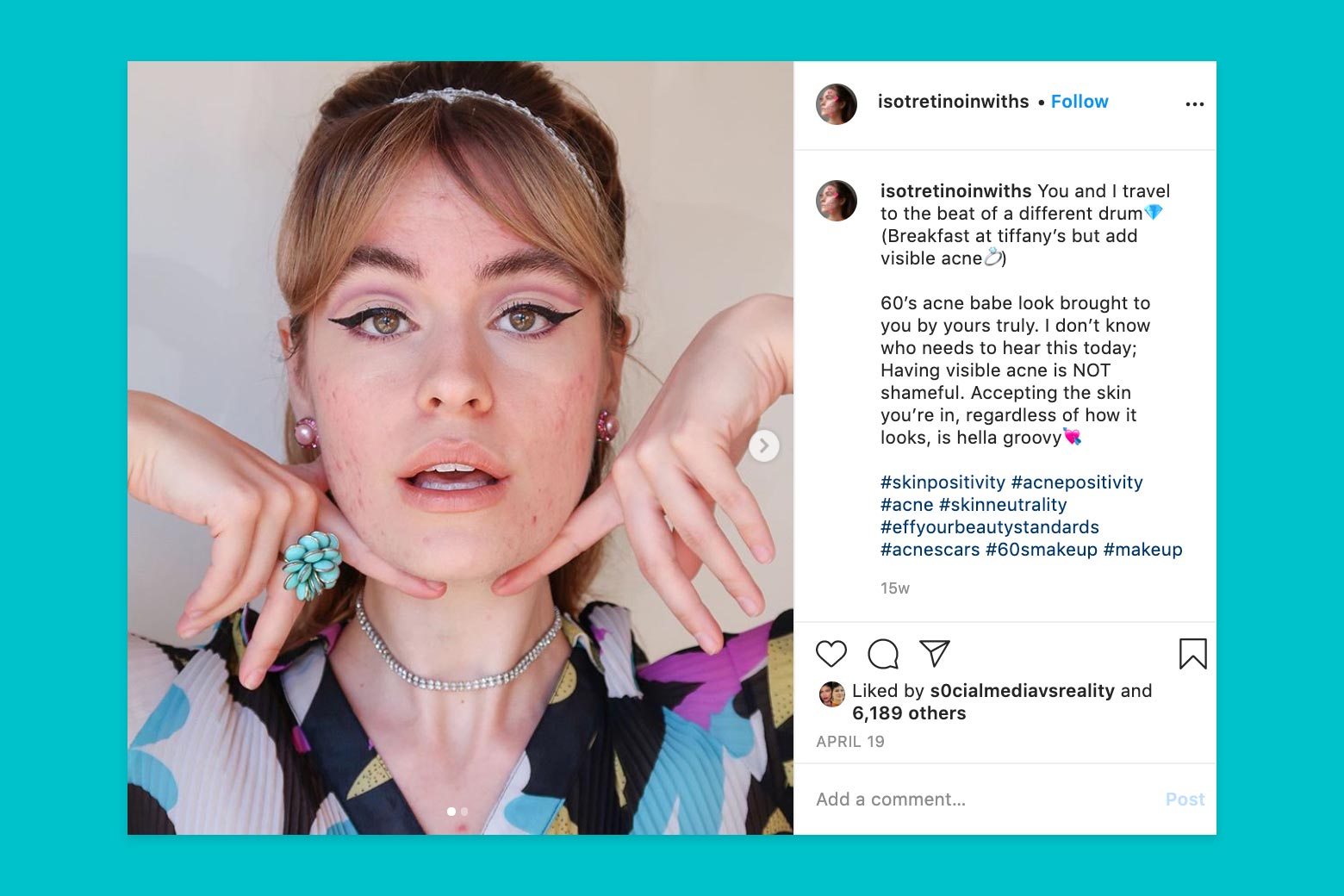

It’s Sofia Grahn, an acne positivity Instagrammer based in Sweden. Her handle, “Isotrentinoin with S” is a reference to the active ingredient in the popular medication Accutane, a pill that takes a scorched Earth approach to skin. It’s the top-selling acne prescription in the U.S., and while it dramatically reduces acne for about half the people who take it, it’s known for severe side effects, including dry skin, joint pain, and miscarriages. Grahn went on the medication herself in October 2018, at a point in her life when anxiety about her acne was so severe that she had trouble doing mundane activities like running errands, going to class, and seeing friends. Grahn was one of the people for whom Accutane “worked”: Her pimples noticeably subsided, an evolution that she cataloged on Instagram. But along the way, it gave her headaches and itchiness. And it didn’t erase her scarring, or prevent future, smaller breakouts. Today, her skin isn’t acne-free, but Grahn feels OK about it. It turned out that looking at other people’s pimples, and showing off her own, has made a difference that the drug couldn’t.

Grahn is now part of a small but growing community of people with acne who show off their skin with the goal of destigmatizing it. She’s joined by accounts like @emeraldxbeauty, a self-described “acne model”; @meghamazing, an Indian “acne realist” who created the hashtag #browngirlswithacne; and @dontpopthatspot, a London-based “acne activist.” Accounts like these helped Grahn accept her own skin: By following the #acnepositivity hashtag, Grahn said, she saw people with similar skin to hers for the first time. “I could recognize the beauty and worthiness in other people whose skin looked just like mine,” she said. “So why couldn’t I see that in myself?”

These acne acceptance influencers have their work cut out for them. Over 70 percent of teens in a 2017 survey conducted by a pharmaceutical company said their acne made them less attractive; other studies have found that people are less likely to consider those with acne scars to be happy or successful compared with people with clear skin. In part, that’s because there’s a perception that acne is something that can be fixed—which is only partly true. For all the potions on the market, acne can be difficult, expensive, and painful to treat. Hormonal acne—the broad term for puberty pimples, PMS-related breakouts, and stress-induced inflammation—looks different on everyone, and there is no widely agreed-upon cause. On the Skincare Addiction subreddit, more than 1 million people regularly debate the latest research and treatment options, from strict diets to pricey microdermabrasion. A universal solution, or even one that would pretty well for most people, does not exist.

For some, acne can be pretty much impossible to get rid of. Cystic acne, like Grahn’s, leaves scars that can cost thousands of dollars to laser away, if they respond to treatment at all. “There are so many false promises made to people with acne,” said Isabelle Vallerand, a data scientist at the research firm Glacier RX who has studied the link between acne and depression. In the absence of broad acceptance, the online acne positivity community stands to be helpful in sustaining the mental health of people who have severe skin concerns. “People need to know that they’re not alone.”

But for people with acne, feeling alone is often the end result of years spent watching TV shows, reading magazines, and seeing ads where everyone who appears has perfect skin. Even as Dove ads feature plus-size models, and Aerie underwear photoshoots go unretouched, inclusive campaigns universally show off clear skin. That’s likely because a diverse array of models can help a brand show that their clothes will work for more customers—but for skincare companies, showing pimples in ads “doesn’t make sense from a business standpoint,” says Vallerand. As a result, even though more than 80 percent of people under 30 have breakouts at least from time to time, the condition is almost completely absent in the media.

Acne treatments represent a multibillion dollar global industry and depend on people feeling unattractive and unsuccessful in their skin. As soon as skincare brands tell people they’re beautiful with textured, splotchy skin, they lose a customer. During the time I was doing research for this article, my Instagram feed became inundated with targeted ads for skincare products. Whenever I scrolled through pictures of my friends’ cats and memes, I would invariably be interrupted by targeted ads for “breakout-battling” foundation, “zit-zapping” patches, and “acne-fighting” pillowcases. Some of these ads featured plus-size models, models with wrinkles and gray hair, and, in one case, a person with a colostomy bag. But they all had one thing in common: perfect skin. It was OK to love myself, these ads said, as long as I was unleashing a blitzkrieg on my pimples.

Almost every commercial image presented to me was completely rid of the acne that I knew existed around me in real life. Of 62 ads for skincare products I counted over six weeks, only two actually showed people with acne—and both were people in “before” pictures. Everything I owned and every action I took suddenly started to feel like a threat to my skin. Was the slice of pizza I was eating going to give me pimples? Was my pillowcase harboring dangerous microbes that attacked me while I slept? Had my $8 drugstore concealer been deemed “acne safe”? What did “acne safe” even mean?

Among all the anti-acne images and ads are posts like Grahn’s, featuring beautiful people with pimples and scarring. This is pushing brands to take up the mantle of acne acceptance, if slowly. The influencers that Gen Z looks up to “are normalizing pimples, and brands are responding,” says Shanti Maung, a trend forecaster at the marketing firm Trendera. Acne cane be an “Instagrammable moment,” explains Maung. “Flower power” acne patches, made by a brand called squish, feature rhinestones and are marketed to festivalgoers. Another brand, Starface, has an entire section of its website dedicated to people’s posts wearing their shimmery translucent star stickers over their pimples. “Acne … but make it fashion,” one caption on an influencer’s photo showing off the star stickers reads. Grahn was featured in a foundation campaign for the makeup brand Charlotte Tilbury that deemed her pictures “flawless before, flawless after,” perhaps only a slight improvement on the usual “before/after” paradigm, but an improvement nonetheless. In sponsored posts on her Instagram account, she takes a more inclusive tone. Earlier this year, she did a post for a company called Clear Start, showing off her scar-speckled face next to a pile of toner and lotion, which she wrote improved her breakouts—but didn’t, apparently, cure them. In the caption she wrote, “I have let go of the image of perfection,” adding, “your skin is doing its best.”