Lessons from aging Japan: losing vibrancy with few structural reforms

As well known, Japan has one of the fastest aging population in the world, reducing the size of the working age population. On the one hand, because labor participation declines significantly beyond the age of 60, senior citizens have increasingly exited the labor market. On the other hand, smaller child population has reduced the number of new graduates entering the labor market. Shrinking working age population has a direct negative impact on potential growth but the key question is whether it also reduces productivity or, in other words, whether it is a double whammy for Japan’s growth.

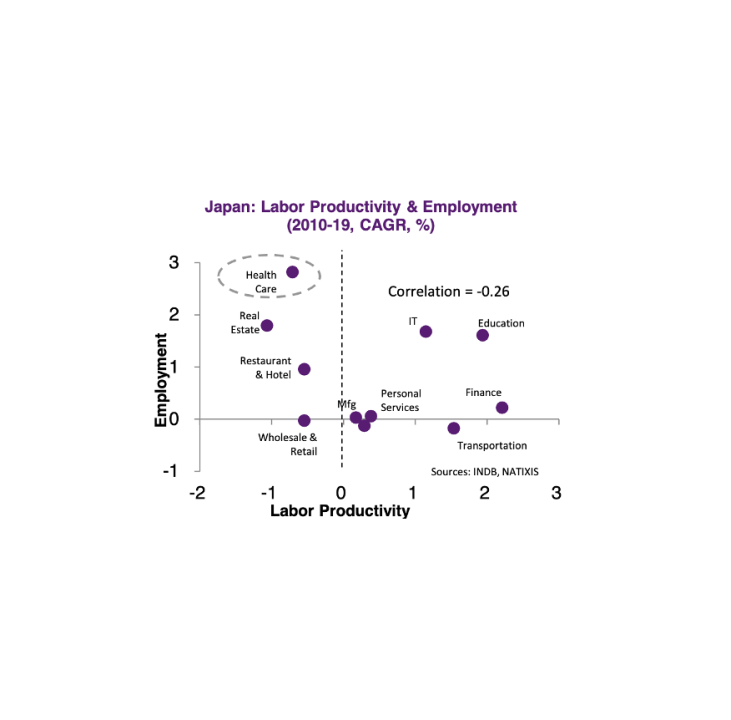

While it is difficult to prove the causality, labor and total factor productivity have been coming down in Japan for the last three decades. At the same time, the share of employment in health services has continued to increase on the back of aging population and is by now the third largest most important sector in terms of employment.

These developments suggest that introducing robots in sectors with low labor productivity such as health care, retail and tourism could alleviate the negative impact of Japan’s aging population, by lifting labor productivity. On a different front, labor market reforms such as removing the inequality between full-time and part-time workers would be essential to increase mobility in the labor market.

Finally, with aging population, the government has arguably limited room to turn around these ongoing negative trends. With increasing social security payments, the government debt has already ballooned to 201.3% of GDP in 2019 and growing debt service payments. To make progress in fiscal consolidation, public investment as well as public funding for education and research and development is being cut and will continue, pushing down potential growth. This vicious circle in terms of the allocation of public expenditure and potential growth is further pushed by the so-called “Silver democracy”, by which elderly voters prefer to support bigger expenditure in health and pensions.

Given the above, it seems quite difficult for Japan to push up productivity and, thereby, potential growth in the foreseeable future. In other words, the silver lining of aging remains limited for Japan.

Full report available for NATIXIS clients.

Senior Adjunct Lecturer, Department of Economics, University of Maryland

3yThe article raises an important issue, not only relevant for Japan, which is slightly ahead of others, but for all developed (and many emerging market) economies, including my country of origin (Finland). How to offset population aging and declining labor market participation while maintaining resources to care for elderly and protect social safety nets? Technology is hoped to provide solutions, but at the same time it raises a host of other socio-economic policy issues that need to be decided, and may require a complete reform of compensation and tax systems. A lot of crucial questions (for current and the next generation) to sort out. Also a test for the survival of market-driven economies and economic policies, I think.