Editor’s Note: Traveling by car between San Diego and the San Francisco Bay area where their son and three grandchildren are domiciled, co-publishers Don & Nancy Harrison like to explore California’s cultural attractions.

-Fourth in a Series –

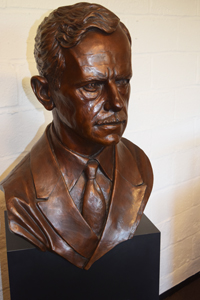

DANVILLE, California – The playwright Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953) grew bored and frustrated by what passed for theatre early in his life. There were few stories told that connected with reality; instead, theater essentially was spectacle – lots of costumes, big sets, predictable plots and one-dimensional characters.

He wanted to change all that, suggested Tory Starling, the educational technician at the Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site. He experimented in various forms of theatre. Lazarus Laughed, the play that first attracted me to his work, had hundreds of mask-wearing characters who grappled with a world turned upside down by this Jewish man’s experience of returning from the dead. The idea that there was no death, only life, as Lazarus proclaimed, was upsetting to the powerful classes of the ancient world. The Jewish establishment feared that such news would drive Jews to the arms of Jesus, who had raised Lazarus from the dead. The Romans who had Judea under their thumb feared that if people no longer were afraid of death, they would not submit to their rule.

As weighty and relevant as the subject of death was, Lazarus Laughed was too bulky a play to be successful. For practical reasons—like the cost of production—it was rarely performed after its publication in 1926. It remained simply the 19th full-length play that the reflective O’Neill wrote and the world all but forgot between plays that won for him Pulitzer Prizes, such as Beyond the Horizon (1920), Anna Christie (1922) , Strange Interlude (1928) and Long Day’s Journey into Night (1957, posthumous award).

O’Neill and his third wife, the actress Carlotta Monterey, moved to their hilltop, Asian-themed Tao House in Danville with its commanding view of Mt. Diablo in 1936, just after winning the Nobel Prize for his body of work. They remained there until 1944, when O’Neill was afflicted with hand tremors. Unable during World War II to find reliable, able-bodied servants who could drive him to doctor’s appointments, he and Carlotta moved to San Francisco and later back to the East Coast.

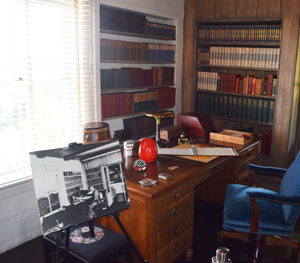

In Danville, O’Neill sought to write a cycle of 11 plays for audiences to watch one after another about an American family’s life in the 19th century, but he abandoned that project as, again, too impractical. In his upstairs study, which had two large desks so he could work on a multiplicity of projects, he wrote in pencil, for Carlotta to retype, some of his best-known plays: The Iceman Cometh (1939), Long Day’s Journey into Night (1941), and A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943).

These plays were largely autobiographical, Starling informed us after driving us in a National Parks Service van from the town of Danville up the mountain to the historic site, and then, by foot, zig zagged to O’Neill’s front door through a serpentine path laid out in accordance with the Asian belief that evil spirits only travel in a straight line.

Starling took us to a downstairs room where family photos were on display. There was his father James O’Neill, an actor who had played the role of Edmond Dantes of The Count of Monte Cristo for thousands of performances in numerous cities. “Later in life,” commented Starling, “he regretted selling out; he felt that he had wasted his talent, that he could have been a great Shakespearean actor, but instead chose the safe route and made a bunch of money, with which he was able to support his family.”

Eugene’s mother, Mary Ellen, who was better known as Ella, was a secret drug addict. She had given birth to Eugene in a New York City hotel room, while following James on his circuit. She took morphine to deal with her post-partum pain and became hooked. “It was a family secret,” said Starling. “They tried to keep it away from others, even Eugene didn’t find out about it until he was 15 when his brother (Jamie) and father told him after Ella tried to drown herself in the river outside the cottage in New London, Connecticut.”

In one of the photos, the family is sitting on the porch of that cottage, which was the setting for Long Day’s Journey into Night, in which the four main characters are his father, mother, older brother, and himself, named as Edmund in honor of a third brother who had died early in life.

Learning of his mother’s attempted suicide was a turning point for O’Neill. “He had been a devout Catholic until then, but he started to question everything, including his religion. That was the beginning of his journey looking for different reasons to explain why things happen. It led him on a path of self-destruction.”

At that point in his life, O’Neill often accompanied his older brother Jamie who “had been hanging out in bars and bordellos.” Although he was accepted at Princeton University, he was expelled after the first year for truancy. He tried writing for newspapers, gold prospecting in Honduras and Argentina, and joined the Merchant Marine. While he loved his life at sea, he drank up his earnings in bars during ports of call; impregnated and then married his first wife, Kathleen Jenkins, to whom Eugene O’Neill Jr. was born; attempted suicide, was stricken with tuberculosis, and was sent to a sanitarium – all by the age of 22. Many of these events were recapitulated in The Iceman Cometh and in Long Day’s Journey into Night.

On the opening night of Long Day’s Journey into Night, “the audience did not know how to react; they were awe-struck,” Starling recounted. “They sat there, they didn’t applaud. The actors thought they had bombed. Then the curtain came up and the audience rushed the actors; they had felt a connection to the actors and the characters they were playing.”

She added that the reaction “speaks volumes about O’Neill’s work; which deals with universal concepts – pain, suffering, family, things we can all identify with. His plays continue to be relevant today because of that. People could see themselves up on stage.”

During O’Neill’s stay in the sanatorium, “he reevaluated his life,” Starling told us. “He wasn’t able to drink there, and he was under care. Then he decided he wanted to be a playwright.” In Provincetown, Massachusetts, “he met with a group from Harvard University that started putting on his works, which were wildly popular right away. They were intimate, small productions, with simple costumes, and he got famous pretty quickly.”

The room with the photos was laid out to represent O’Neill’s youth. It includes a player piano named “Rosie,” which came from a bordello.

While most furniture at the Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site is not original, the National Park Service worked from photos taken by Life Magazine photographers to recreate O’Neill’s dwelling as closely as possible.

In the living room, Starling said, “sometimes Eugene O’Neill would read aloud to Carlotta and sometimes act out the plays for her. Most people get the idea from photographs that he was morose, but he had a good sense of humor, even goofy. We have recordings of him singing sea shanties. He didn’t take himself quite as seriously as people think. His plays can be dark, but there is always a vein of humor throughout his plays as well.”

Off the living room was a guest room, but Carlotta made sure that anyone who stayed with them knew that O’Neill was not to be disturbed during the day while he was in his upstairs study. In fact, guests were not permitted to go upstairs while he was working, but were invited to descend a path to the large swimming pool where O’Neill took laps every morning.

Among guests who stayed at the house were the director John Ford, the actress Ingrid Bergman, and O’Neill’s children by his first wife Kathleen Jenkins and second wife, the writer Agnes Boulton. Eugene’s and Agnes’ son was Shane, and their daughter, Oona, eventually was banned from Tao House – disowned by O’Neill because at age 18 she went against his wishes and married a man O’Neill’s age, the actor Charlie Chaplin, who was 36 years older than Oona. Chaplin and Oona went on to have eight children, among them the actress Geraldine Chaplin, who portrayed Tonya in the movie Dr. Zhivago. Geraldine’s daughter, Oona, also became an actress, portraying Talisa Maegyr in Game of Thrones.

Our small group ascended the staircase where we first saw Carlotta’s bedroom, in which a prominent feature was a special raised bed for Blemie, their dog, who is buried by the barn on the property, where a tombstone contains this epitath: “ Blemie: Silverdene Emblem. Born Sept. 20, 1927 England. Died Dec. 17, 1940, Tao House. Sleep in Peace Faithful Friend.”

O’Neill also wrote a lengthy Last will and Testament for Silverdene Emblem O’Neill, in which in the voice of the dog, he said, in part:

I have little in the way of material things to leave. Dogs are wiser than men. They do not set great store upon things. They do not waste their days hoarding property. They do not ruin their sleep worrying about how to keep the objects they have, and to obtain the objects they have not. There is nothing of value I have to bequeath except my love and my faith. These I leave to all those who have loved me, to my Master and Mistress, who I know will mourn me the most, to Freeman [the chauffeur] who has been good to me, to Cyn and Roy and Willie and Naomi and — but if I should list all those who have kissed me it would force my Master to write a book. Perhaps it is vain of me to boast when I am so near death, which returns all beasts and vanities to dust, but I have always been an extremely lovable dog.

Carlotta and Eugene had separate bedrooms; each having been married multiple times and having been single in the interim, they preferred their privacy. Besides, our guide informed us, “Eugene had insomnia; he would get up at night, and sometimes write.”

O’Neill’s own bedroom was painted a shade of gray that reminded him of the fog at sea, which he enjoyed. The bed is one of the few original pieces in the home. Before they moved to the East Coast, the O’Neills had sold it back to Gump’s department store in San Francisco. When the O’Neill Foundation asked Gump’s to donate it, the request was at first ignored. But then the actress Katherine Hepburn wrote a letter, chiding Gump’s. “Think and be kind, you are Gumps,” she wrote. Gump’s thought and complied. Hepburn had portrayed Mary in Long Day’s Journey into Night in which Jason Robards also had starred as Jamie. Robard’s wife was on the committee that organized to preserve the O’Neill house after its subsequent owners, the Carlsons, were ready to sell it.

To raise money to purchase the house and grounds, community activists decided to put on a benefit performance of Hughie, one of O’Neill’s one-act, two-actor plays. Jason Robards agreed to star in it. Now, O’Neill plays are put on both in the town of Danville and in the barn, which has been outfitted to seat 100 in an intimate setting.

At Foundation fundraisers, commented Starling, “We have a two-hour period before the production, so people can have a picnic, explore the grounds and get a feel for O’Neill and what was going on while he was writing the plays.

“We leave his study light on during the performances so you can imagine that he is up there writing while you’re watching the performance!”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworldo.com