UT System oil money is a gusher for its administration — and a trickle for students

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/08/17/UniLands-Richmond_018_TT.jpg)

WINKLER COUNTY — On a square of dirt surrounded by sun-scorched grassland, hundreds of miles from Austin, a huge iron pumpjack creaks up and down. It runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week, generating as much as $7,000 worth of oil per day.

It’s surrounded by thousands of others, drawing from billions of dollars' worth of oil and gas under this ground, which is all controlled by the University of Texas System. And thanks to the fracking boom, workers are pulling out far more oil from each square of West Texas dirt — millions of gallons a day.

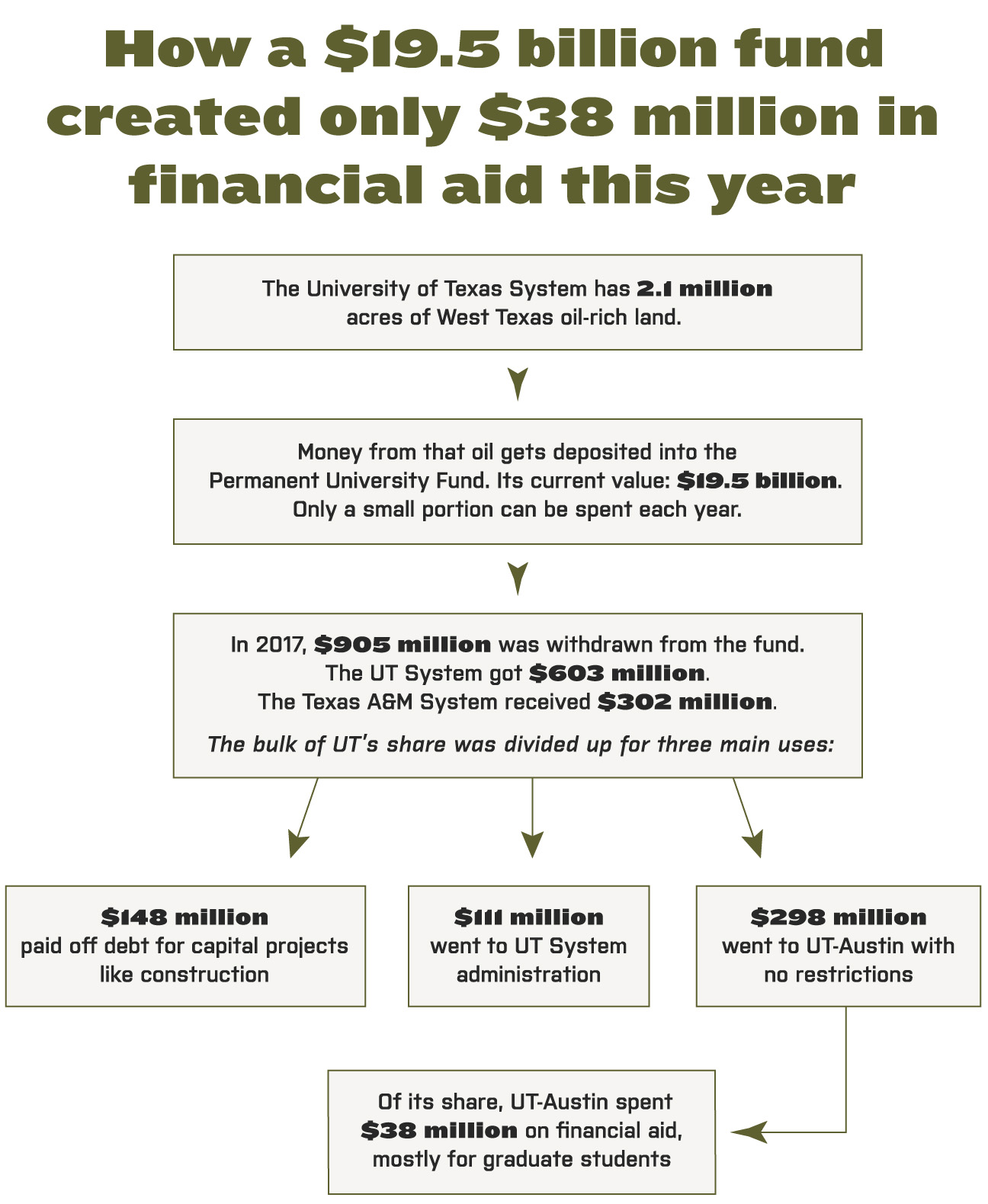

Each barrel pulled from the ground adds a few more dollars to the Permanent University Fund, a $19.5 billion pot that supports an endowment for the UT and Texas A&M University systems.

In recent years, the annual cash payout from this oil fund has exploded: In 2011, the UT System — which oversees UT-Austin and 13 other campuses — received $352 million from the fund. This year, it will receive $603 million, and about half will flow directly to its flagship campus in Austin (the Texas A&M System will receive about $300 million).

That has helped UT System become one of the richest educational institutions in the world, part of a rarefied club that includes Harvard, Yale and Stanford.

But unlike the other members of the club, the UT System is a public institution and must disclose how it spends the money.

Those disclosures show that the wealth hasn't created a windfall for students. The money that filters down to them in the form of financial aid amounts to a trickle of roughly $40 million. That includes about $3 million for UT-Austin’s 40,000 undergraduates, and approximately $35 million for its graduate students.

Meanwhile, the amount the UT System has spent on its general administration quadrupled since 2011 to a peak of $143 million in the last academic year. And it has committed huge sums to some controversial initiatives proposed by the past two UT chancellors, including:

- $215 million to buy 300 acres of empty land in Houston, with no concrete plans for how to use it. After a political backlash, the system now says it plans to sell the land.

- $100 million devoted to an in-house educational technology startup that has struggled to meet its goals.

- $141 million on a new 17-story office tower in expensive downtown Austin to house hundreds of system employees.

All those dollars could have otherwise gone directly to UT-Austin, which has seen its financial support from the state decline and has raised its annual tuition by $1,500 since 2010.

UT System leaders say they are being smart with the oil money. State law imposes some spending limits, and they say their administrative expansion has meant big savings for UT campuses by consolidating expensive services.

But many state leaders, and some members of the system’s own governing board, have begun questioning how all those millions are being spent.

“It looks to me like an entity that has a lot more money than they know what to do with,” Sen. Kel Seliger, R-Amarillo, chairman of the Senate Higher Education Committee, told UT’s chancellor during a tense committee hearing in January.

The nine-member UT Board of Regents, which approved all those big-ticket expenditures in recent years, will meet this week. Since a group of more skeptical regents joined the board this spring, many members have signaled that they’re ready to rein in the system’s spending.

“There’s a very significant and growing top-down, expensive architecture that … provides, I believe, very little, if any, return on investment,” Regent Janiece Longoria said during a meeting this May.

The complaints have created a tense situation for UT System Chancellor Bill McRaven, who has defended many of the big-ticket projects and whose contract expires in January. This week he will tell regents that he wants to cut $15 million from the system administration's budget. Even then, the budget will be three times what it was in 2011.

“The UT System Administration’s first and foremost responsibility is to the institutions — period!” McRaven wrote in response to questions for this story. (Read his responses here.) “However, running a 21st century university system requires leveraging the size, scale and diversity of the 14 institutions to better serve the broader educational and health care needs of the people of Texas.”

Endowment nearly doubled during fracking boom

UT gained access to its oil riches more than 140 years ago, though no one knew at the time. In 1876, when Texas ratified the sixth and current version of its Constitution, the authors ordered the state to create a “university of the first class.” Over the next few years, the state set aside 2.1 million acres in West Texas to help fund an endowment for the new school.

At the time, the land — which covers an area larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined — seemed like little more than useless brushland that could barely support cattle grazing.

But after oil was discovered in Texas in 1901, UT System leaders began to suspect there was oil under their West Texas ground. In 1923, a wildcatter named Frank Pickrell was the first to strike at a well called Santa Rita No. 1, kicking off a rush that hasn’t stopped since.

These days, the university land is just as hot and dry, but not nearly as sparse. Hundreds of oil wells dot the horizon, surrounded by networks of dirt roads, pipelines and big man-made pools of water. Now that the fracking boom has caused a new oil rush in West Texas, more than 7,000 roughnecks, drillers and truck drivers trudge out of hotels and portable buildings each morning to work on the land.

As the oil and gas flows into pipelines, the money flows into the Permanent University Fund, which has grown from $10.7 billion in 2010 to $19.5 billion today.

The system preserves the fund for the long-term by spending only a small fraction of it every year. Still, that amounts to $603 million for the UT System alone in 2017 — more than the Legislature spends on its main financial aid program for low-income students across the state.

The Texas Constitution says the UT System can only spend the oil money on capital projects and administration. Whatever the system doesn’t use goes to UT-Austin, which is free to spend it on whatever it wants. But the university spends only a small fraction of the money on student financial aid.

Experts who’ve looked at the scant information available on private universities say they probably use their endowment funds the same way.

But politicians from both parties are calling for change. Last year, even Donald Trump jumped into the debate, when the then-presidential candidate accused colleges of spending their “massive endowments” on “things that don’t matter.”

“Too many of these universities don’t use the money to help with the tuition and student debt,” he said at a Pennsylvania campaign rally. “Instead, these universities use the money to pay their administrators, or put donors’ names on buildings, or just store the money, keep it and invest it.”

$100 million for a startup

Universities faced grim financial news in 2011 as state lawmakers passed historic budget cuts — including more than a half billion dollars from higher education. But thanks to the oil boom and some good investments, the UT System learned the oil fund would deliver a record cash payout of $400 million in the coming year. Flush with that new cash, administrators found new ways to spend it.

Hoping to unite system leaders behind a new vision for the future of higher education in Texas, Chancellor Francisco Cigarroa locked himself in his official residence with a group of advisors for nearly two days. He emerged with what he called a “Framework for Excellence” for the system — one that would largely be financed by the oil fund.

The framework had nine “planks,” including improving science education, building new research centers, hiring new faculty and developing online learning tools. All nine regents approved the plan without asking a single question, and they gave Cigarroa an initial investment of $244 million to implement it.

The plan was seen as so visionary that Cigarroa was invited to the White House to talk about it — twice.

One of the priciest items was one that the regents had pushed him to include: The Institute for Transformational Learning, envisioned as a kind of startup technology company to create digital learning tools at UT campuses and beyond.

It wasn’t clear how the institute would sustain itself in the long term, or exactly what products it would develop. But regents approved $50 million to launch it.

The system started by pumping $10 million into one of the hottest new education trends at the time: Massive Open Online Courses, which could be taken free by anyone, anywhere.

But the value of the courses to UT students was never clear. In one case, 44,000 people from around the world signed up for “Energy 101,” taught by famed UT-Austin professor Michael Webber. Only a fraction of them finished the 10-week course, and hardly any were UT-Austin students — probably because the course couldn’t be taken for college credit.

Within two years, the attitude toward the courses soured.

“The System should stop investing millions of dollars on gambles like these, which lack financial exit strategies and viable forms of revenue,” the editorial board of UT-Austin’s student newspaper wrote in 2014.

Yet in an exuberant presentation to the board of regents in August 2014, the Institute for Transformational Learning’s leaders didn’t talk about any of that. Instead, the director hyped other products that the institute was developing and declared that the UT System was “poised to define the future of higher education.”

Another staff member told the regents about a “revolutionary” program to help college dropouts finish their degree online. And a “beautiful, engaging” digital tool that would let UT students access all their learning materials on a mobile device. Then came a “cross institutional marketplace offering industry-driven multilingual stackable modules, certificates and specializations to health professionals.”

It wasn’t clear exactly how these products would work or whether they would generate any revenue. Regents didn’t ask.

After noting that the oil fund payout was continuing to rise, they allocated tens of millions more dollars in oil money to expand online learning and campus enrollment — including another $48 million for the institute.

The institute continued to expand even after Cigarroa resigned. After McRaven became chancellor, its annual budget grew almost tenfold, to $25 million and a staff of 50 in the last academic year. But most of the products that had initially generated so much excitement — the online courses, the program for college dropouts and the platform for health education — are no longer part of its main strategy.

For example, the system had high hopes when it launched one of the institute’s products, an iPad app called TEx, at UT-Rio Grande Valley. The app let students access all their course materials, measure their progress, and communicate with classmates and professors. But while some students praised the tool, many others found the technology difficult and counterintuitive. The school won’t be using it this fall.

According to a memo obtained by the Tribune, UT-RGV will instead go back to its old online platform from an outside vendor. As a result, the memo says, “students will likely incur additional costs.” It’s not clear how much.

Costs had already been going up for students. In 2016, the regents approved tuition increases at all the system's campuses. At UT-Austin, that increase was projected to raise $30 million.

Richard Vedder, a professor and expert on college endowments from Ohio University, said that many universities have spent their wealth on initiatives like the Institute for Transformational Learning.

“There’s justification for wanting to innovate and all, but ... that’s a lot of money,” he said. “I would throw a million, or two million, into a pilot study, maybe. But $100 million — that’s tuition for 10,000 students.”

"We have more money than sense"

Today, after six years and about $50 million of UT System money spent, enthusiasm for the institute among many of the regents is waning fast.

“It appears that we spend a goodly sum on initiatives like this,” new regent Longoria said at an April meeting, two months after she began her second stint on the board. She added that to the outside observer, it appears “we have more money than sense.”

“Let me assure you, we take the stewardship of these resources very seriously,” McRaven countered, adding that the institute would eventually generate revenue and was a “worthwhile endeavor.”

“I don’t disagree with that,” Longoria responded. “But why has it taken over five years, and we still don’t have a product?”

Soon after that meeting, the institute’s top two executives resigned.

In retrospect, system leaders say that the initial vision might have been too ambitious.

“There was not the foundation of a business plan at the time [the institute was launched],” said Steve Leslie, a UT System vice chancellor who began overseeing the institute in 2015.

The institute is still working on a plan to achieve financial sustainability, Leslie said. Preliminary budget documents suggest that the institute will face cuts, but don't specify how much.

Meanwhile, its next big play — a redesigned cybersecurity program at the University of Texas at San Antonio — is set to launch this fall.

Leslie said the best is yet to come for the institute.

“It was expensive,” he said. “But it led to where we are now, which has also been expensive.

“But ... what this platform is going to provide is worth it, if we get to the finish line in ways that we think we will.”

"A risk and a gamble"

Cigarroa stepped down in early 2015. The regents tapped McRaven, a UT-Austin graduate and retired Navy admiral, to take his place.

He had no higher education experience, but his hiring generated a lot of buzz. He’d orchestrated the famous Navy SEAL raid that killed Osama Bin Laden. And McRaven was passionate about cutting bureaucracy and red tape.

But McRaven wanted to make his mark, too. Almost a year into the job, in November 2015, he presented his own ambitious vision for the UT System called the “Quantum Leaps.” The leaps, he said, were “about improving the human condition in every town, every city, for every man, woman and child.”

And they would make heavy use of the UT System’s cut of the oil fund, which by then had grown to $544 million.

Some of the Quantum Leaps aligned with the goals of most public universities — increasing student success, hiring talented faculty and growing diversity. Others address specific interests of McRaven’s, such as the creation of a UT Network for National Security and “an effort akin to the Manhattan Project to understand, prevent, treat and cure diseases of the brain.”

None raised more eyebrows than the last Quantum Leap, which was also among the most expensive — a plan to expand into Houston by buying hundreds of acres there.

As McRaven spoke, artist’s renderings flashed on a screen, showing dozens of buildings, along with sports fields and tree-lined boulevards. McRaven said he didn’t know exactly how the land would be used, but that it would create an “intellectual hub” for the UT System and be a “game changer.”

McRaven wrapped up his hour-long presentation to the regents by declaring that the system would “act with unparalleled boldness.”

“I hope your bold gamble in allowing this old sailor to lead this great institution will be a winning hand,” he said.

The boardroom burst into applause, and McRaven got a standing ovation. Regents were just as thrilled, if not more, than they had been by Cigarroa’s own nine-part vision four years earlier. And just as before, they gave their new chancellor tens of millions of dollars from the oil fund.

But outside the room, the Houston plan was a surprise. Many state legislators learned about it from the news, or from an e-mail sent right before McRaven’s speech. Houston lawmakers were furious, fearing the new campus would bring unwanted competition to the nearby University of Houston.

In the following weeks, McRaven received a cascade of requests from legislators urging him to slow down the process. But he didn’t. In January 2016, just three months after McRaven announced the Quantum Leaps, the UT System closed on the first 100 acres. It would eventually secure more than 300 acres at a cost of $215 million, all of which would come from the oil fund.

The criticism mounted. During public hearings, legislators pressed for more details about McRaven’s plans for the land. McRaven repeatedly insisted he didn’t have any yet. Meanwhile, lawmakers were pondering another round of major cuts to higher education funding — and they wanted to know more about how the UT System was spending its oil money.

Tensions peaked this January, when McRaven told members of the Senate Finance Committee that the hundreds of millions' worth of cuts they were considering would have a “potentially devastating” effect on the UT System.

Lawmakers eventually backed off on the cuts, but that day the senators weren’t sympathetic.

“I don’t think you give a damn what the Legislature thinks,” said Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, practically yelling. He said he couldn’t believe McRaven was complaining about state funding cuts while spending hundreds of millions of dollars on empty land.

McRaven responded testily: “If you don’t do something big, bold, you don’t become a great University of Texas System. This could very well be a risk and a gamble.”

Senators had other examples of what they called unwise spending from the oil fund. They questioned the $1.5 million McRaven wanted to spend on studying how to brand the UT System. And they complained about the $141 million office tower in downtown Austin, which had been approved before McRaven was hired.

McRaven pushed back again. He pointed out that the new office tower would save money by consolidating the system’s staff from five buildings into one. He added that the state Constitution places limits on how the oil money can be spent.

But the tide was turning against him. The same day as the tense committee hearing, lawmakers appointed three new UT regents, who promised they would tell system leaders “no” when administrators pursued projects that weren’t in the best interests of the state.

Within weeks, McRaven changed his mind on the Houston land. In a hastily called press conference on March 1, he announced that the tract would be put up for sale.

“I was unable to build a shared vision for moving this project forward,” he recalled recently.

'This is all about the students'

Since then, the pressure on McRaven has only increased, even from people who had previously been supportive of his goals. At a board meeting in May, Regent Steve Hicks apologized to his colleagues for losing focus on cost-cutting in recent years. Now, he said, he’s ready to dig into “how and where we spend our system resources.”

Several other regents agreed that the system administration needs to trim its budget and cut staff.

The board’s chairman, Paul Foster, promised to comb through system spending for possible savings. The first changes could come as soon as this week when the regents approve the system’s 2018 budget.

“This is all about the students, and we’ve got to make sure that we never lose sight of that,” Foster said.

In written comments to the Texas Tribune, McRaven rejected the idea that the UT System has grown too big. Much of its increased budget, he said, has been the result of efforts to lower costs at the university level.

For instance, he said the system has spent tens of millions on software licenses, property insurance and digital library services that otherwise would have been paid for by each campus. He also said many of the new staff were hired to ease burdens for individual campuses.

Many of those initiatives were implemented before McRaven took over. Cigarroa, who signed off on many of them, said they were attempts to keep tuition down at campuses other than UT-Austin, since state law prohibited those schools from receiving cash from the oil fund.

"To actually save money on [those] campuses, you have got to start thinking a little creatively," Cigarroa said.

Not all of those moves were successful, however. In 2014, the system committed $31 million per year to centralize audit and IT services in hopes that the savings would allow campuses to keep tuition flat. But the budget for those projects grew by millions because of problems with the IT transition, and the auditing consolidation proved to be a failure. The system decided in May to return the auditors to the campuses.

Overall, McRaven said the system has an “excellent track record” at saving money for the campuses through consolidation. But regents are pushing for more of the oil fund to go directly to UT-Austin. Last month, they instructed McRaven to redirect $26 million from the system to the university. That means UT-Austin can expect $338 million in oil money for the upcoming school year.

It’s unclear if any of that new money will go to financial aid. UT-Austin officials say they prefer to use their oil funds to raise the school’s stature by hiring new faculty and promoting research. The oil money only makes up 10 percent of the school’s revenue, and administrators say they use other sources of money to provide financial aid to students.

In a brief chat with reporters recently, McRaven tried not to make too much of the fact that change may be coming. The regents are in a “constant review process” when it comes to spending, he said, “always looking at how we manage access and affordability, and an exceptional faculty.”

Asked if he would like to stay on as chancellor after his contract expires, McRaven simply said, “I’m really enjoying working with this board ... the new board members are great to work with. We have not had a discussion.”

Pressed further, he again said, “I can tell you I very much enjoy working with the board.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas System, the University of Texas at Austin, Texas A&M University and the University of Houston have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Contributors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Matthew_Watkins_EG_TT_01.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Neena_1.jpg)