Antibiotic resistance is predicted to cause 10 million deaths a year by 2050.

But there may be some hope thanks to ground-breaking research into using viruses to attack the worst superbugs.

Bacteriophages (also known as phages) are viruses that infect bacteria and new research has shown they can be very effective in combatting antibiotic resistant superbugs.

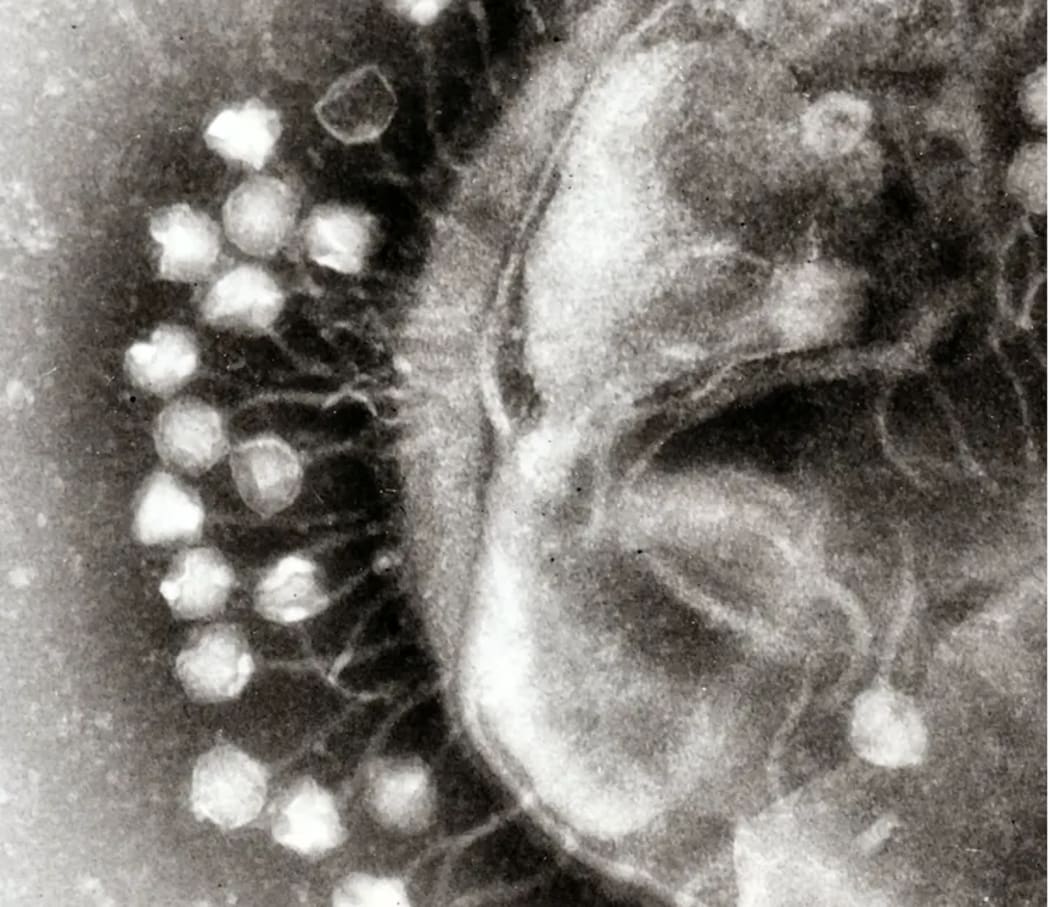

Phages attach to the outside of bacteria, initiating the killing process. Photo: Dr Graham Beards/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

One of the Australian scientists at the forefront of this research, Jeremy Barr of Monash University, told Jesse Mulligan that we have probably reached the limit in terms of the number of antibiotics available to us.

“The big problem with antibiotics is we’ve probably found most of the ones that are available. Antibiotics are a finite resource, we’ve got about 20 or so antibiotics that are really useful for treating these infections, so what we have is probably all we’ve got.

“It’s quite scary that some of these bacteria have come resistant to most if not all the antibiotics, we really have nothing left in our antibiotic toolkit to fight these infections.”

Hospitals are where superbugs pose the biggest problem, he says.

“In the near future you may be faced with the choice do I have this treatment knowing that I’ve got a significantly increased risk contracting one of these superbug infections.”

Barr’s research team has focused on what WHO says is the world’s most dangerous superbug - Acinetobacter baumannii.

“This bug is at the top of the threat list, it causes many, many infections and deaths in hospitals around the world.”

So, what exactly is a phage?

Simply a bacteriaphage that only infects and kills bacteria, Barr says – and they are not a new discovery.

“Bacteriaphages were discovered about 100 years ago, they are not a new thing by any means, they’ve been used in lots of parts of the world particularly eastern Europe.

“But they are coming back now with this antibiotic resistance crisis, and the fact that we’re losing these antibiotics, more and more researchers are looking at using phages as an alternative or supplement to fight some of these super bugs.”

Phages are abundant, Barr says.

“They are the most numerous biological entity on the planet.”

His research team source them from waste water.

“What we would do is we would take a superbug and we would use the sewage sample to find the phage that would infect and kill it.”

Phages are often able to rapidly kill antibiotic resistant bacteria, he says, but there is a hitch.

“The scary thing is, just like the bacteria became resistant to antibiotics, they also became resistant to our phages.”

However, as the bacteria becomes resistant to the phage, they become re-sensitised to the antibiotic to which they were previously resistant, he says.

“It’s almost a one-two punch where we can treat the bacteria with the bacteria phage, kill it or weaken it, and in doing so it is actually re-sensitised to an antibiotic which it used to resist.”

Barr says he is optimistic that in the future phages will be used in a clinical setting to fight superbugs.