‘The joy and energy was unforgettable’

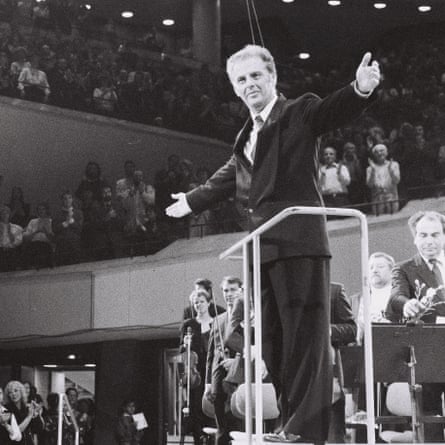

Daniel Barenboim, pianist and conductor who has lived in Berlin since 1991 and is leader of the Berlin State Opera and its Staatskapelle orchestra.

I happened to be in Berlin recording Così fan tutte with the Philharmoniker. The day after the Wall fell, the orchestra asked if I would do a concert with them on Sunday morning, 12 November. I said yes, on two conditions: it must be free and only for citizens of East Germany.

When I arrived at the hall for a short rehearsal, thousands of people were queueing. Some had arrived at 4am. We played Beethoven’s first piano concerto and seventh symphony and the Così fan tutte overture. The joy and energy of those people and the orchestra was unforgettable. It was much more than an appreciative audience of a wonderful orchestra.

Afterwards, there were a lot of people backstage but I needed to get ready for the next recording session. As I said goodbye, I noticed a lady of about 60 leaning against a wall with a young man of about 30. I asked if I could help her. She shyly gave me a bunch of flowers and thanked me. “I have something to tell you,” she said.

This woman had got married 30 years earlier in East Berlin and had a son. But her husband fled to the west with their baby and she had had no contact with him. She had lit a candle every night. But the day before the concert, a man knocked at her door. “It took me quite a few seconds to realise that he was my son,” she said. They came to the concert to celebrate their reunion. It touched me enormously. I told her I would invite her to come any time I played or conducted in Berlin. She said: “No, Mr Barenboim. I don’t need an invitation. I will just be there.”

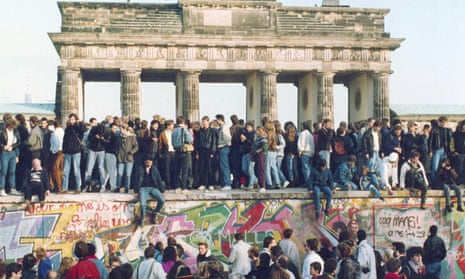

After the concert, the Staatskapelle orchestra asked if I would be its director. One of the first decisions I took was to hire German musicians from both sides. I’m conducting again this Saturday night at another free concert in front of Brandenburg Gate. It will bring back memories of a day that changed the whole world.

‘Our souls could not keep up’

Ute Lemper, 56, is an Olivier award-winning German singer and actress who starred in Chicago and the original Paris production of Cabaret.

I grew up in West Berlin and, in the 1970s, we would drive across the border to visit my aunt and uncle. I have vivid memories of every single car seat being removed by the East German officers when we came back, in case we had smuggled out relatives. Life in the east seemed so grey.

After studying in Vienna, I moved back to West Berlin in 1984 to be an actress. The city was a little scarred island in the middle of the eastern bloc. But we had this thriving, progressive cultural scene, free spirited and subversive. I was angry about this divide, but at the same time inspired. In 1988, I worked with some East German artists. There was a feeling that a revolution was about to start. When the wall came down a year later, I was overwhelmed with joy and relief. But history was moving fast. Our souls could not keep up. Nor could the politics or the arts. We were all trying to get a grasp of it.

The wounds that were inflicted during 30 years of separation were deep. We had grown apart and been taught to reject each other for too long. Many East Germans experienced years of identity crisis and have now turned to the opposite of what they had been forced to think: far-right politics are strong and growing. I always thought healing would take at least as long as the Wall was up for. But I was wrong. I think it will take another generation.

‘There were no bananas left in West Berlin’

Wim Wenders, 74, is a German director whose films include Wings of Desire, Buena Vista Social Club and Paris, Texas.

I spent the autumn of 1989 in a camp near a one-horse town in Australia called Turkey Creek. I was looking for film locations. I could not have been further from Berlin. There were no phones but there was a fax machine in Turkey Creek’s only general store. I had given their number to my office in Berlin – just in case.

When I cut my foot swimming, I had to drive to Turkey Creek, to see the doctor. After he fixed my bandages, we went to the store to buy provisions. The owner pulled out a rolled-up fax and handed it to me, his face glowing with joy. He said it had arrived a few days ago.

The printing was terrible but I could recognise some shapes. Were people dancing on top of a wall? The Wall? The headlines were illegible. I stared at these black pictures. Had the Wall fallen? How long ago? Hadn’t Russian tanks intervened? What was going on in Berlin?

I finally got a line to Berlin and woke up somebody from my office. The Wall was indeed open, Berliners were beside themselves with excitement – the rest of the world as well – and there were no used cars or bananas left in the whole of West Berlin. Actually, there was also no West Berlin any more. Then the connection got cut off.

We never drank any liquor out there in the desert, but that day I made an exception. I picked up a few bottles of wine, a few cases of beer and a lot of ice. I got back to the camp after dark and we finished every bottle.

‘I was classed as subversiv-dekadent’

Mark Reeder, 61, is a musician and record producer from Manchester who helped shape Berlin’s techno and trance scene. In 1990, he founded his own label, MFS, in East Berlin.

On one of my first trips to East Berlin, I collared a young, new wave-looking lad who had lilac drainpipes and spiky hair on the U-Bahn. I asked him about the music scene there and if there were any underground punk concerts. He shook his head. It turned out he was a Stasi informer. In his report, he said I was looking for the political underground. Punk was seen as anti-state in this workers’ paradise. I was classed as “subversiv-dekadent”, which isn’t a bad accolade.

Later, in 1989, I was back in the east to produce an album for the indie band Die Vision in the state-owned recording studios. It was obvious East Germany had already started to fall apart. There were demonstrations and people were trying to get out. In early November, I decided to take a short break with some friends. Somehow, I talked them into a road trip east to Bucharest.

We left Berlin on the gloomy night of 8 November. Days later, in a Hungarian hotel along the way, I saw a photo on the front of a newspaper showing a man standing on top of the Berlin Wall drinking a bottle of Sekt. It confused me until I read the headline: “East German troops begin partial demolition of the Wall.” I thought, “What? What wall? Oh, fuck – they mean the Wall.” It hit me like a hammer.

We drove back to Berlin, which had completely changed. The streets teemed with Trabants, the cars of East Germany, and moustachioed men in cheap tracksuit jackets and stone-washed jeans. Women had big hair and flowery leggings. There was an incredible, positive new energy.

In early 1990, I managed to finish producing the Die Vision album, which I called Torture. It became the soundtrack for many East German kids who had not yet been infected by the new sound of techno. That Stasi informer had thought I had some sort of political agenda to corrupt the youth of East Germany with western music. How right he was.

‘They said look under your car for bombs’

Christine Maclean, 66, managed the East Side Gallery, a painted section of the Berlin Wall. She is the author of Two Berlins One Wall.

I was in my 20s when I got a job as PA to the cultural attache at the British embassy in East Berlin. It was 1982, and for four years I would commute every day from my flat in West Berlin through Checkpoint Charlie. The first time, it was a bit like visiting someone in jail. The doors close and part of you thinks: “I hope they let me back out.”

I was part of the British Council. Its job was to promote the English language, hosting film nights, that sort of thing. But East Germans were too frightened to come because they knew they would be tailed by the Stasi when they left. We had a library but nobody would borrow the books. It wasn’t easy to make friends in the east, which I found sad. And going home was like time travel: everything would be grey during the day, then I’d go back home through Checkpoint Charlie and see all the neon lights and colourful clothes.

I was fed up of constantly looking over my shoulder. One day, we got a letter suggesting we look under our cars for bombs. It was time to leave. Then I went to bed one night, not feeling well – and friends woke me up because the Wall had come down. I opened the window and could hear the sound of horns. Then I smelled the Trabants. I ran outside.

The next year I saw an ad for an assistant to David Monty, an artist who wanted to turn a long section of the Wall in the east into an outdoor gallery. There was always painting on the west side – mostly graffiti – but you could never touch the wall in the east. I ended up organising more than 100 artists, including many East Germans. When I worked at the embassy, I had been unable to understand how they felt – and now they could paint and touch the Wall itself. It was very powerful.

‘I was in a studio with the Bad Seeds’

Blixa Bargeld, 60, is a German musician best known for his work with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and his own group Einstürzende Neubauten.

I grew up in West Berlin and it never felt like the Wall was going anywhere. The day it came down, I was in a recording studio with the Bad Seeds. We had the TV on and saw that something was happening, so we went outside. It was the middle of the night but the streets were filling with people.

A few weeks later, I managed to play in East Berlin with my band. We’d tried to do it for years and this time we were just waved through the old border. East Berliners came into our dressing room. A couple of years ago, I needed surgery. I had a meeting with the doctor and he brought a poster from that 1989 show. He’d been a medical student in East Berlin and was now head of the clinic.

‘The euphoria was incredible’

Margaret Hunter, 71, is a visual artist who has lived in Berlin for 34 years.

I came to West Berlin in 1985 to work under Georg Baselitz, after studying at the Glasgow School of Art. The west of the city had this feeling of absolute freedom. But wherever you went, you always came up against the Wall. When it fell, the euphoria was incredible. I was curious and soon visited and exhibited in East Germany. I was welcomed and felt an affinity with the people.

In 1990 I was invited to make a painting on the Berlin Wall, in the previously forbidden east, as part of the East Side Gallery. We worked together – Romanians, Italians, Spaniards, Americans, French – all artists who had something to say. We couldn’t really understand each other, but the atmosphere was charged. A year later, the gallery got monument protection.

My painting was called Joint Venture and had two large mask-like heads joined by black lines to symbolise communication and exchange. I added figures on both sides of the heads signifying individuals who had to bend and stretch to come to terms with their new situation, especially in the east.

I still live in the flat I moved to in 1985 and think often about painting the Wall – the wall I had watched on TV, with people tunnelling under it or being shot trying to escape. It’s a sombre thought.

‘People in the street had overthrown an army state’

Thomas Ostermeier, 51, is artistic director at Berlin’s Schaubühne theatre.

I grew up in a provincial town in Bavaria, so West Berlin felt like an island utopia to me. The same spirit drew me there that drew the likes of Iggy Pop and David Bowie. I worked nights in a petrol station and spent my days making music and reading books. It was this special place where we could live with the fact of being imprisoned by this Wall that we never imagined could come down.

I was in Hamburg the day it happened and immediately got in a car with friends and went to Berlin. The next spring, I remember riding by bike every day from West to East Berlin and thinking: “Wow, how fast things can change.” I was discovering a country where people spoke my language, yet it was completely different. I immediately felt at home in the east and lived in a squat. So many people had moved west and suddenly there were these vast territories – apartments, warehouses, factories – where this vivid arts scene moved in and flourished.

There were concert spaces and soup kitchens. I put on my first show in the backyard of a squat. The future seemed bright – people in the street had overthrown an army state. One of the first things I did was go to the Berliner Ensemble, where original Bertolt Brecht productions were still playing. This completely different, Brechtian perspective became very important in my own work – theatre that questions society, with characters whose actions are a result of social circumstances and not just psychology. Living in East Berlin gave me new tools and skills for making theatre.

‘We were given 100 Deutschmarks each’

Christian Schwochow, 41, is a German film and TV director whose work includes two episodes of The Crown.

I grew up in East Berlin, in a rented flat very near the Wall. My father was from a family that was critical of the system and he had been to prison for trying to escape. By 1989, more and more people were applying to leave – and being accepted. My parents had applied in early 1988. They were accepted on the morning of 9 November 1989 and had 72 hours to leave. That night, the Wall came down.

We crossed into West Berlin in the morning. I was 11 and remember thousands of other East Berliners lining up for the 100 Deutschmarks we were all being given. The first thing we did was go to a library and ask for a card. On the second day, we went to the famous Grips Theatre to see Linie 1, a musical about a young woman who gets stuck on a Berlin metro line. We didn’t have much money and my mother just begged the ticket office to let us stand at the back. The lady was so moved she gave us front-row seats. That was a big day for me.

‘They let more people in than they should – it was electric’

Madeleine Carruzzo, 63, is a Swiss violinist and a member of the Berlin Philharmonic. She played in the concert for East Berliners conducted by Daniel Barenboim.

I joined the Philharmonic in 1982. West Berlin was a wonderful place to live but it was always a problem for me to feel that the other part of the city was not free. None of us felt that would change. From the balcony of the concert hall, we could look into the east. Soon we would watch a transformation.

The day after the wall opened, the orchestra had the idea to play a concert only for people from East Germany, who we had never been able to play for. It was good luck that Daniel Barenboim was with us at the time and he immediately agreed to conduct. I remember crowds of people trying to get in. It’s difficult to describe the emotion that day. It was intense. I remember feeling joy that these people were free to come and listen to our music.

I think they let more people in than they should. It was electric. There were people crying and some of my colleagues were close to tears. I felt like I had to give it everything I had and at the end people were giving flowers to everyone. There was a lot of music in Berlin at the time but classical goes very deep. It has the power to go to the soul and we could all feel that that day.

‘I heard animals howling at night’

Tim Mohr, 49, is an American writer whose work as a DJ in East Berlin inspired his book Burning Down the Haus: Punk Rock, Revolution and the Fall of the Berlin Wall

I was a pretty unsophisticated teenager growing up in Reagan’s America. But I had enough misgivings about it to want to live somewhere else. When the wall fell, we got the western, triumphalist narrative and I was sceptical. Even as a teen, it was hard to believe a latent desire for McDonald’s was enough to bring down a dictatorship. But I didn’t have evidence to the contrary until, two years after unification, I got a chance to go to East Berlin to work in the English department at Humboldt University.

I was 22 and arrived as pretty much your stereotypical stupid American who thought everyone would be wearing lederhosen and drinking beer. Instead, I ended up in an eastern high-rise out by the zoo. I could hear the animals howling at night. It was nothing like what I expected but I was lucky because I’d basically stumbled into what was happening behind this great facade - this unbelievable, kaleidoscopic scene that was more colourful and energetic than anything I’d experienced.

I was supposed to stay for a semester and ended up staying for a decade as a club DJ. I became friends with former eastern punks. And here was my evidence. These were the people who’d fought the dictatorship, who had been detained, interrogated and beaten. And they were opposed to unification. They had hoped to establish an independent, idealist East Germany. When they realised that wasn’t going to happen, they reverted, and created a new oasis where they could be who they wanted to be. That was the basis of the initial Berlin nightlife scene. The book I’ve just done about these people I knew is my life’s work.

‘I packed up my studio and moved to Berlin’

Philip Pocock, 64, is a Canadian artist and photographer who documented punk culture in Berlin in the 1980s.

It was a fascinating time. I remember the free jazz an art collective use to play on a platform overlooking the east, where it could be heard by neighbours on their balconies. The Wall itself was like a screen with naked concrete facing the east and colourful, provocative graffiti facing west. My favourite graffiti from Berlin in 1982 was a sly command on grey concrete: “Transport the Wall to the National Gallery.”

In 1987, US president Ronald Reagan was about to visit and I went looking for protests. Days earlier, I’d been introduced to a group of punks who had greeted me and my camera with a friendly headbutt. They joined students at the protests. Those who were hungover from slam-dancing at the SO36 club staged a sit-in, nursing beers and listening to pirated punk tapes. Occasionally, one would stealthily get up and throw a cobblestone through the Commerzbank window. I got tear-gassed for the first time that day. The punks were flabbergasted.

I had moved back to New York by 1989, but when the Wall fell it hit me like a brick. Art follows history, not money. I packed up my studio and moved to Berlin.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion