Before Larry Thomas — who died Sept. 9 at age 73 — opened Cincinnati’s The Movies Repertory Cinema in 1980, the following theaters had tried some variation of an art/indie/documentaries/classics format in the 1970s:

The 20th Century, Studio, Place, Alpha, Mount Adams, Union Terminal, Bijou-Roxy-Ritz, Beacon Hill, Midtowne (formerly The Guild) and probably some others. All of them failed; many are probably completely unfamiliar names to most readers today. The Movies, originally called Movieola, took over the space once occupied by one of those forgotten names, The Place Cinema, at 719 Race St. in downtown’s Garfield Tower Apartments. (Cincy World Cinema is located there today and moved in after Cincinnati Shakespeare Company relocated to their new OTR theater.)

The Movies under Thomas’ ownership — with partners — ultimately closed, too, in 1991. But nobody who was around at the time has ever forgotten it the way they have those others. For that matter, those who care about “alternative” cinema today are aware of Thomas’ and The Movies’ legacy: It lives on as a piece of important Cincinnati cultural history. Like the original Ludlow Garage, it was a breakthrough arts accomplishment.

Thomas sought to encourage his patrons to regard movies as a very lively and serious art form, not just a commercial product; one that needed to be treated with respect and exhibited with knowledge — he once returned a print of Japanese director Akira Kurosawa’s classic Yojimbo without allowing it to be screened because the distributor inadvertently send a dubbed version.

At the same time, he had a knack for making the theater itself a fun destination responsive to audience suggestions. I should know about his generous spirit: At my request, he once brought in a guilty-pleasure monster movie called Alligator, a long way from Kurosawa. Its screenwriter, John Sayles, was just emerging as an auteur director with Return of the Secaucus 7, and I was curious about his writing history. Somehow, I remember nothing about Alligator today, nor if anyone besides me attended. (I’m not sure I attended.) But I appreciated the gesture. Thomas gave me a personal connection to the theater and I attended frequently, such as on a first date with my future wife. (We saw The Music Teacher, a French film.)

Michael Schlesinger, one of Thomas’ original partners until he moved to Los Angeles, recalled one particular event that showed Thomas’ active outreach to his patrons.

“When it became obvious that George Romero's Knightriders was never going to play Cincy, we brought in a print from Indianapolis and held a private midnight screening for our most loyal customers (and fed them Cassano pizza). We didn't get out until almost 3 a.m., but everyone had a sensational time,” he wrote in an email.

The audience trusted him to do right. He was also super-generous with the Cincinnati Film Society, a group he had belonged to before opening his theater and continued to help out by booking movies that complemented the group’s own mini-festivals and guest appearances. He helped in another way, too — supplying popcorn for CFS events.

“I remember going to Moviola's lobby and picking up the largest garbage bag of popcorn I'd ever seen,” says Dennis Kiel, a CFS board member, via email. “I assume we paid him something for it, but I don’t know.”

Considering Cincinnati’s past failures with a full-time art/indie house before The Movies, Thomas really had courage in presenting a repertory format where four to five different films a day would play. He’d have new foreign and American independent pictures mixed with classics and cult favorites from around the world, including Hollywood. And he offered lots of quirky, indescribably weird stuff. His role model, he used to say, was the old Empire Theatre on Vine Street in Over-the-Rhine, where second-run features often changed daily. It was a refuge.

But Thomas wasn’t appealing to nostalgia with such a format. There was a very smart reason for this approach. Given that he needed to build an audience of Cincinnati cinephiles, his scheduling forced people to hurry up and commit to seeing movies if they were at all curious. He didn’t want to tie up his one screen for a week with a single film if there wasn’t a large clued-in audience for it here, however well it was doing in New York. But the limited screenings created buzz when shows sold out. Hundreds were turned away from Secaucus 7, for example, a film about a reunion of 1960s radicals that could have been a tough sell. Nothing creates demand like scarcity.

It helped that The Movies was a cool place to be, with its comfortable rocking-chair seats and a good stereo-sound system. And Thomas kept prices low — $2 per movie in 1980; just $2.75 by 1986. He also impressed the press with his knowledge, good humor and sincerity, and his first-run movies got prompt reviews in the dailies.

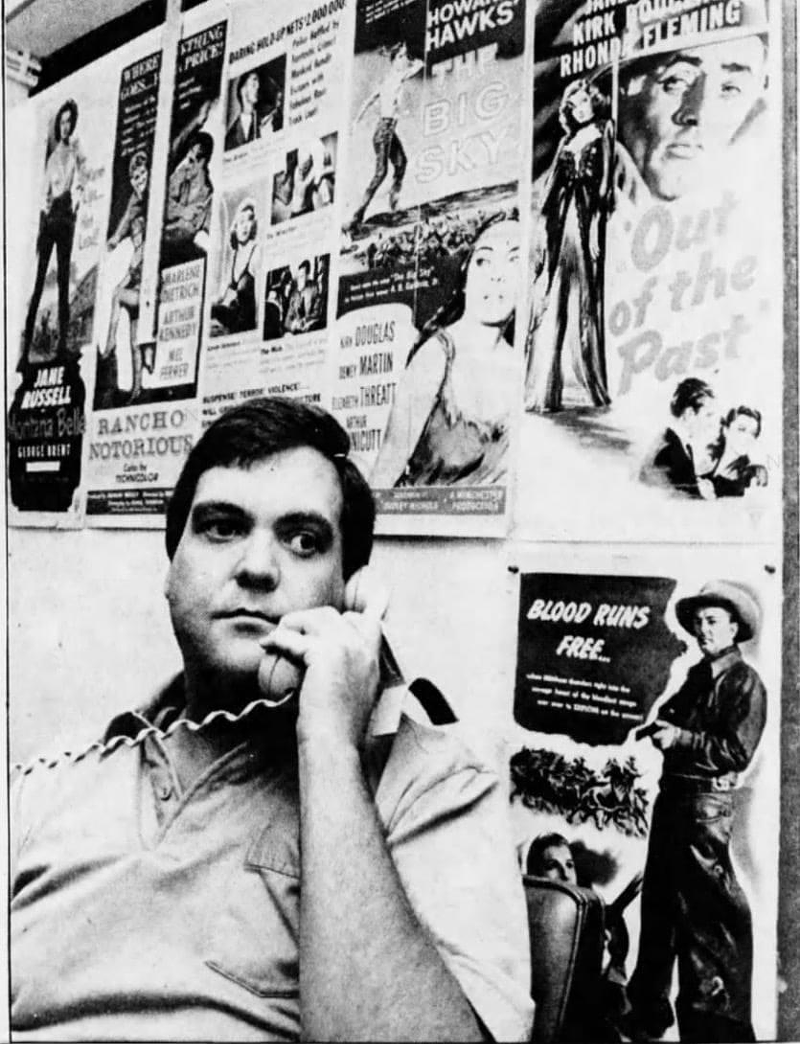

He had a secret weapon, too. One reason his theater is remembered so well today is because his former patrons have never forgotten those poster-size black-and-white calendars he would mail out with his upcoming schedules. In many homes, they were displayed on refrigerator doors. They were exciting to read and discuss with friends and probably as eagerly anticipated as whatever magazines you subscribed to. According to an Enquirer Sunday magazine story I wrote in 1981, roughly a year after The Movies opened, the mailing list had already increased to 8,000 from 1,500. And when I wrote about Thomas again for a 1986 magazine story, it was up to 30,000.

Whoever designed that 1981 Enquirer story recognized early on the visual power of those calendars. One was used as the story’s lead art. I look at it now — the different fonts, the small images, the right-hand column for movie notes, the bold names of wonderful actors, directors and film titles — and I want to go back to The Movies right now.

That one calendar featured Fellini’s City of Women, the French-Algerian Ramparts of Clay, Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers, Jason and the Argonauts, David Bowie and Marlene Dietrich in Just a Gigolo, Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, and Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not. It was an embarrassment of riches.

Thomas was something of a child prodigy as a film booker. He was from Oak Hill, West Virginia and his father owned the theater in nearby Fayetteville. He lived close to the Oak Hill theater that his uncle and aunt owned. When he was 5, he saw the 1952 re-release of the original King Kong. It made quite an impression — he not only vividly remembered the action and the features of Kong, but he also learned the name of the film’s distributor, RKO. Later, he started reading Variety and got interested in the kind of movies that never played small-town West Virginia. Really, he got interested in everything to do with movies.

At age 16, his father let him experiment with double bills. He paired A Thousand Clowns, an adaptation of a Broadway play about a New York City comedy writer forced to temper his eccentricities in order to have legal custody of a nephew, with Munster, Go Home! His surprising aesthetic was born, as was perhaps his delightful sense of humor.

Thomas also would go with his father on Cincinnati business trips and would walk around a downtown filled with all the dazzling first-run movie theaters that now are all gone.

“It was a big city and you had the option of walking up and down the street and having your choice of things to do,” he explained in my 1986 story. He eventually moved here and began a career booking films for distributors.

One person Thomas got to know in the Cincinnati film community was Phil Borack of booking agency Tri-State Theatre Service. When Borack went into film production and made 1978’s Harper Valley PTA starring Barbara Eden, Thomas invested in it. He used his profits to open The Movies, with Borack as one of his partners.

When I wrote about Thomas and The Movies in 1986, the angle was that the city of Dayton was financing him and two partners to build a new downtown indie/art house there. It was a chance to expand The Movies empire. We drove up together to look at the site, near the Oregon District, which didn’t impress me as being particularly attractive and was also noisy. But Thomas was excited because he had heard he would be near a very busy intersection, which would be good for business.

That new theater, in an appealingly small building wedged into the landscape like a piece of pie, did open in 1986 but lasted just two years under The Movies’ management and booking policies.

“The theater just ran out of everything: time, money, luck,” Thomas told The Dayton Daily News. (With a new name, The Neon Movies, it has continued to operate as a hip cinema and Dayton landmark to this day.)

I was out of Cincinnati when The Movies closed here in 1991, but I could see why — times had changed and the repertory concept was now a hindrance for a single-screen venue. Indie cinema had exploded in popularity in the wake of the Sundance Film Festival and films like Sex, Lies, and Videotape; patrons didn’t need to be carefully herded to screenings in cities like Cincinnati. They were clamoring for more, more, more. And the film distributors didn’t want their titles to share screens and thus reduce their daily showings and possible revenue.

The Esquire reopened as a first-run art/indie house in Clifton in 1990, with three screens and a total of 400 seats. In 1999, it expanded. We now also have Mariemont and Kenwood theaters mixing mainstream offerings with smaller first-run releases, and Cincinnati World Cinema operates out of The Movies’ old location with special presentations. (The Esquire also has started to mix in classics.)

Thomas went on to an impressive second career with Cincinnati Public Radio, and continued to do bookings for a small network of independent theaters. Upon returning to Cincinnati, I caught up with him for a 2014 CityBeat story about his involvement with the then-72-year-old, 800-seat Kentucky Theatre in downtown Lexington, an old movie palace that the city had saved. His great joy was programming its summer series of restored classics.

“For so many years all you could get were worn prints — spliced, scratched and with defective soundtracks,” he said. “Any time you could get hold of a new 35-millimeter (film) print of something, it was a big deal. Now with digital prints, they’re stunning.”

Thomas’ innovative approach to repertory programming suddenly seems newly relevant because of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. Smaller indie/art theaters had to close for months; reopening now in a socially distanced environment has been a learning experience. During the months when these theaters were closed, their distributors started streaming some of their first-run specialized titles; they may not want to stop. And, of course, Netflix has become a rival. Also, drive-ins are now back.

Whenever the movie business gets back to normal, the art houses may have to re-energize their audiences. The Movies repertory format might serve as a model. And those paper calendars would still look good on a refrigerator door.

Thomas is survived by wife Charlotte Reed Thomas, brother John Thomas, brother-in-law Doug Reed (Frances Dickson) and his nieces Grace and Vivianne Reed. The family asks that in lieu of flowers, please send donations to Cincinnati Public Radio or the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Editor's note: Steven Rosen used two stories he wrote for The Cincinnati Enquirer — on Sept. 6, 1981 and June 1, 1986 — and one from CityBeat is 2014 as source material for this piece.