Floating Wind Farms Are About to Transform the Oceans

One way or another, life just off the coast of California is about to change.

Alla Weinstein did not invent the floating wind turbine. This is something she wanted to make clear early in our Zoom call, as if she were worried I’d give her too much credit. “I don’t need to invent. There are plenty of inventions,” she said. “But a lot of inventions die on the grapevine if they aren’t carried through.” What Weinstein does is carry them through.

For that, she does want credit. When I asked if she’d put the idea of floating offshore wind generation in the minds of California’s energy commissioners, she bristled cheerfully. “I would put it more strongly than that,” she said, shaking her auburn curls. “I didn’t give anyone ideas. I basically told them, ‘This is what needs to be done.’” The state needed clean energy, she reasoned, and she knew a couple of inventors with the technology to produce it: a floating platform designed to support a wind turbine on the surface of just about any large water body in the world.

If you haven’t been following the tortured saga of offshore wind power—or even if you have—you may not recognize how completely floating offshore wind technology stands to alter the global energy landscape. Just 10 years ago, installing offshore wind in the Eastern Pacific Ocean was technologically impossible: Conventional wind turbines typically sit atop giant steel cylinders called “monopiles,” which have to be driven into the ocean floor and rarely sink deeper than 100 feet. Other structures, known as “four-legged jackets,” can go as deep as 200 feet. But the continental shelf off California breaks fast and steep, dropping to depths of more than 600 feet not far from shore. Floating platforms, meanwhile, can sit on the surface of oceans thousands of feet deep, and can be assembled onshore and towed to their various destinations—as far out as transmission cables buried in the seafloor can extend back to land.

And while floating wind technology currently costs more than the conventional monopiles, that won’t be true for much longer. Once developed, a single platform design can be installed along hundreds of miles of coast with very little modification, making mass production possible and cost reduction likely. “You can literally have one design of a support structure that will be the same for California, Oregon, and Washington,” Weinstein said, “and maybe even Alaska.” A floating offshore wind farm doesn’t require pile driving or heavy construction in rough waters. “The only thing you have to do offshore is hook [the platform] up to the mooring that you laid out ahead of time,” said Weinstein.

In the U.S., floating wind technology is poised to revive an industry that just a few years ago seemed moribund, straitjacketed by location constraints, equipment shortages, and wealthy coastal-property owners who wanted their sea views undisturbed. For California in particular, floating offshore wind could be the key to achieving 60 percent renewable electricity by 2030 and 100 percent by 2045, as the state legislature has required. Wind puts electricity on the grid just when solar-saturated California needs it most: in the evening and nighttime, when people come home from work and power up their air-conditioning. The technology could allow the state to retire its last natural-gas power plants, wean its grid off nuclear power, and still have enough clean electricity to power its expanding fleet of electric vehicles.

Not surprisingly, California’s elected officials are manifestly pro-wind. On September 9, lawmakers in Sacramento passed a bill ordering the state energy commission to develop a strategic plan for offshore wind by 2023. Governor Gavin Newsom signed it on September 23.

But large-scale renewable energy is and always will be a fraught business, and offshore wind on either coast is still far from a sure bet. Generating enough energy to make a wind farm profitable requires a lot of space in the ocean, and everything else in that ocean—from fish farms to whale migration routes to Native tribes’ sacred rituals—is a potential obstacle. Offshore wind on the Eastern seaboard has been repeatedly stymied by the inability of government agencies and developers to balance its impact with other uses of the ocean. California has its own whales and fisheries and views to protect, and all of them stand to lose from an industrial project on the surface of the sea.

History has shown that if conflicts aren’t addressed in advance—if local opponents are left to stew in their anger—large-scale renewable-energy projects will founder in the face of organized opposition. And when they do, they will become fodder for conservatives’ speeches on the folly of clean energy. It’s worth remembering that of all the competing interests that undid Cape Wind, the failed offshore wind project once slated for Massachusetts’s Nantucket Sound, the deadliest was neither a fisherman nor a conservationist nor a member of the local Wampanoag tribe, but the fossil-fuel magnate William Koch.

The gripes over offshore wind aren’t always about the views from billionaires’ homes. They can be real and significant: In some places, for instance, the construction and operation of offshore wind could be catastrophic for marine life. In the Atlantic Ocean off the coasts of Rhode Island and Massachusetts, areas slated for wind development intersect with crucial habitat for the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, whose fragile recovery has happened mostly in southern New England. Thirty miles offshore from New Bedford, Massachusetts, meanwhile, the waters will soon be crowded with ships and cranes and pile-driving machinery as the 62 turbines of Vineyard Wind, the first large-scale commercial offshore wind development to be built in U.S. waters, rise above the ocean. Local commercial fishermen fear the disruption of their catch, and the end of their livelihood.

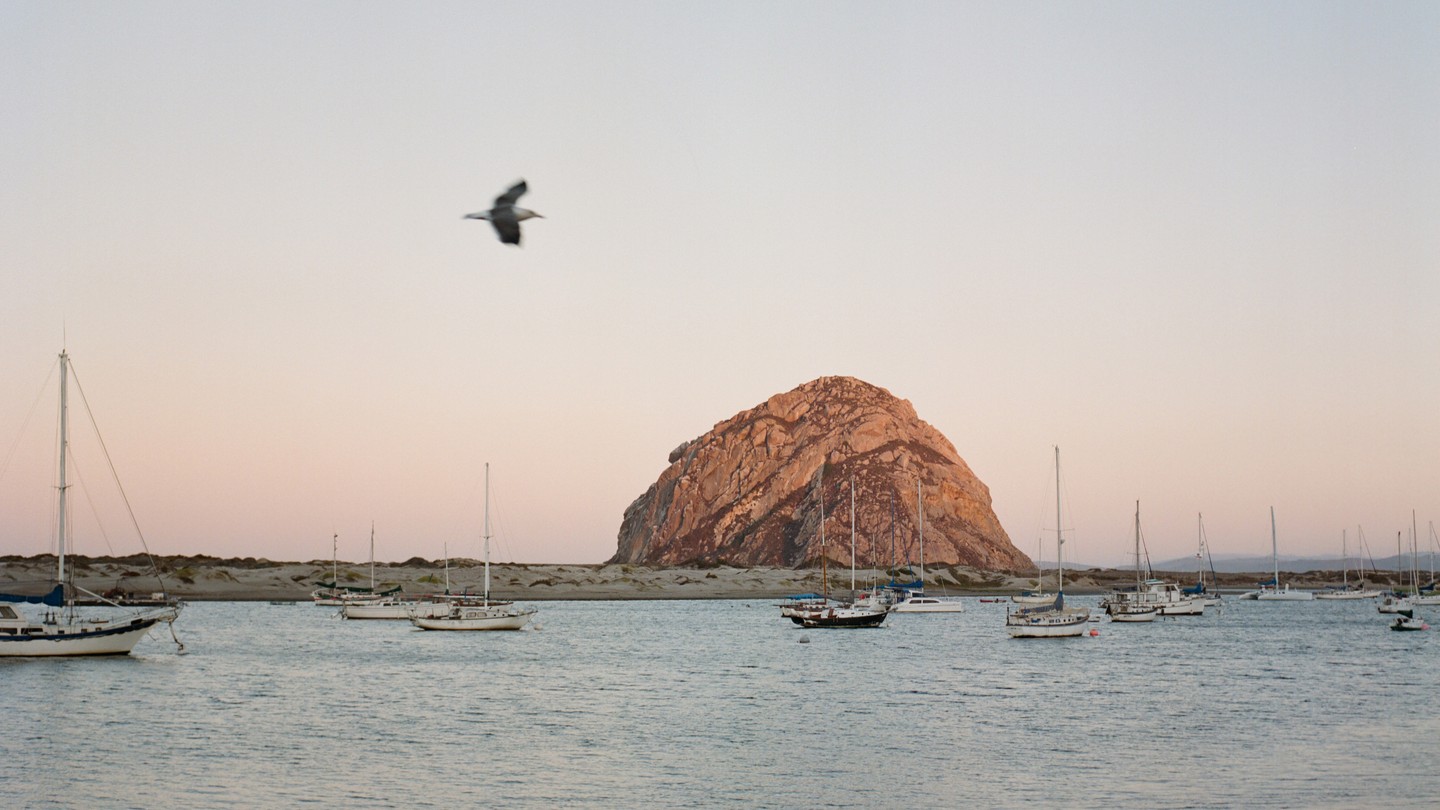

Notionally, at least, floating platforms should limit the impact of ocean-wind generation. But any disturbance to such a wide swath of wildlife habitat carries risks, and the places the federal government has picked out for wind on the California coast—near the fishing village of Morro Bay and farther north, near the city of Eureka—are rich with ocean mammals and fish. Local fishermen in Morro Bay have been here before: 20 years ago, when telecommunications companies laid fiber-optic cables on the ocean floor, “the fish stopped biting for two years,” said Tom Hafer, the president of the Morro Bay Commercial Fishermen’s Organization.

Weinstein, who emigrated from the Soviet Union in her 20s and earned her undergraduate degree in electrical engineering in the U.S., knows all of this. She also knows how to navigate obstacles. For 10 of the 20 years she worked on aviation applications at Honeywell’s test-equipment engineering department, she was the only female hardware engineer. “Then I fell out of the sky and into the ocean,” she told me; in 2000 she met the inventors of a device that would convert the up-and-down motion of waves into electricity. She knew nothing about ocean energy, only that California desperately needed solutions to its historic electricity crisis.

In 2001, Weinstein launched a start-up, AquaEnergy, to deliver clean wave energy to the grid. But the prototype AquaEnergy had planned for Makah Bay, Washington, in collaboration with the Makah tribe, never got past the permitting phase. Not until 2009 did federal agencies even agree on which one of them had authority over what would have been, essentially, a hydropower development on the Outer Continental Shelf. Five years into the venture, an Irish company, Finavera Renewables, bought AquaEnergy, and Weinstein said she “started to realize that [wave energy] was not going to become commercial in my lifetime.”

That same year, two French naval architects, Dominique Roddier and Christian Cermelli, came to Weinstein with an idea for a small, nimble platform, or Minifloat, that could be hauled to previously off-limits places for deep-ocean oil drilling. Weinstein had been looking for a new venture, but she at first turned the two men away. “I told them, ‘I don’t do dirty energy,’” she said. A few months later, they approached her again. They had adapted the Minifloat to support a wind turbine, aiming to solve many of the problems that had held back ocean wind projects. No longer would the installation of offshore wind turbines require a costly barge with a vertiginous crane, capable of hoisting a power box the size of a shipping container atop a post taller than the Washington Monument. With the new innovation, WindFloat, offshore wind power could go anywhere there was water and wind. Weinstein liked that idea better, and with her second company, Principle Power, she licensed the technology from the inventors and set out to develop it.

Roddier tells the story a bit differently: “I told her ‘I don’t like your business plan.’ She told me, ‘Well, I don’t like your oil and gas thing. So why don’t we make [WindFloat] the business of Principle Power?’” Whichever way it happened, Principle Power teamed up with Energias de Portugal in 2008 to develop a floating-platform prototype off the coast of Portugal. In 2011, they successfully installed a floating two-megawatt turbine, just enough to power a small neighborhood. But capacity wasn’t the point: This was the first time anyone had put a multimegawatt turbine on a semisubmersible platform in the Atlantic Ocean.

Designs for floating wind turbines now number in the dozens, including one by the Norwegian company Wind Catching Systems that resembles a billboard of spinning blades. Roddier and Cermelli’s WindFloat systems have been installed off the coast of Scotland and went online in October as the Kincardine Offshore Windfarm, the world’s largest floating offshore wind development. The Norwegian oil company Equinor is putting 800 megawatts of wind on floating platforms in South Korean waters, and Shell Oil has partnered with a Korean venture to develop another 1.4 gigawatts of floating wind nearby. In the U.S., the prospect of floating wind has allowed Maine Governor Janet Mills to declare state waters off-limits to wind projects, for the sake of lobster fishermen, while encouraging the technology in federal waters far from shore. (A demonstration project is in the offing.)

In 2016, Weinstein, under the banner of her new company, Trident Winds, submitted an unsolicited lease request to put 100 floating offshore wind platforms in federal waters, 33 miles from Point Estero, just north of Morro Bay. “I spent six months researching the location,” Weinstein told me. Morro Bay had the transmission lines needed to bring the electricity to market, and local officials were eager to replace jobs lost when the nearby natural-gas plant closed in 2014. Most of all, Morro Bay had wind, at an average speed of 8.5 meters per second: ideal for any wind project, on land or sea. Weinstein’s proposal was a bold move, and when other energy companies took notice, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management determined that there was enough competitive interest in U.S. Pacific Ocean wind energy to explore the prospect in earnest.

Two years later, BOEM officially identified 311 square miles off Morro Bay as a potential wind-energy-development area. It later added two extensions, expanding the total wind “call” area to 399 square miles, 17 to 40 miles from shore. Another 207 square miles have been delineated for wind in the waters off Humboldt County in Northern California, 21 miles from Eureka. Trident Winds has formed a joint venture, Castle Wind, with the German energy company EnBW to develop wind energy off Morro Bay. Several big guns in the energy business, including Shell’s renewable-energy division and Norway’s state-owned oil company, Equinor, have submitted comments to BOEM, indicating their interest. But Weinstein hopes that when the lease auction begins next year, she will have a leg up on the competition: Three years ago, Weinstein initiated talks with the local fishermen on behalf of Castle Wind.

Morro Bay is the home port for about 60 commercial fishermen, who bring in rockfish and wild salmon and Dungeness crab for both local consumption and export. Squid from these waters fetch top dollar in foreign markets, as do black cod and hagfish, or “slime eels”—unknown to most U.S. consumers but hugely popular in Korea. In 2019, before the coronavirus pandemic closed restaurants and froze the export market, Morro Bay’s fishing industry brought in more than $15 million. Weinstein knew early on that the fishermen had to be heard. “I would not be able to imagine walking into somebody’s office and saying, ‘By the way, I’m going to be here, and you, you know, you can kind of go away,’” she said. “The ocean is their office. It is where they work.” The consequences of ignoring local concerns, she knew, would be dire. “To take an attitude of ‘I don’t care what you do; I will be putting things here anyway’—we already have that example, and that was Cape Wind.” Cape Wind’s CEO, Jim Gordon, Weinstein asserted, “didn’t come and talk to stakeholders.”

Gordon has said that the project was undone by “a wealthy and politically influential NIMBY group.” But Weinstein is not alone in her assessment. “There was no level of community engagement that occurred, no discussion; there were no partnerships with towns,” Chris Adams, then the chief of staff for the Cape Cod Chamber of Commerce, told the Associated Press in 2017. “It was kind of like they just showed up and said, ‘This is what we’re going to do, like it or not.’”

Castle Wind and other wind projects proposed for California may not have opponents quite as well-heeled as Gordon did in Cape Cod. But both Morro Bay and Humboldt County border sensitive marine habitat, where animals already contend with container ships, military exercises, and “ghost nets” left behind by fishermen that can entangle the region’s significant population of humpback whales. In the winter and spring, gray whales migrate along California’s Central Coast as part of their annual 12,000-mile route from the Arctic to Baja and back again. Southern sea otters, once almost extinct, drift obliviously in coastal harbors, unaware that anything in their carefully guarded world is about to change. Because one way or another, it will.

The day I met Tom Hafer on his boat, the Kathryn H, it was 65 degrees and overcast in Morro Bay. Above the docks on the boardwalk, a black lab pulled an elderly man eagerly toward the water; a Millennial couple, comfortably adipose, pushed their sleeping baby in a stroller. There was neither a McDonald’s nor a Starbucks in view, only fish stands and cafés, their facades faded by the seaside mist. The air was filled with the rumble of diesel boat engines and the high-pitched bickering of seabirds. The scene was so surpassingly hunky-dory, in fact, that it was hard to remember that elsewhere in California, yet another unprecedented wildfire was reducing a similarly quaint town to ashes.

Hafer, an independent commercial fisherman, was at the time of our interview prepping for a three-day trip north in search of spot prawns. As I arrived, a young man in jeans and a sweatshirt was stacking large, flat containers, like supersize pizza boxes, on the boat’s stern. He collected some money from Hafer, then promptly left. “He lasted one day,” Hafer said, shaking his head. “Young kids just don’t want to work anymore.” To the seagull that alighted on the starboard gunwale to peck at the boxes, full of bait, he had a more charitable attitude. “He lives on my boat,” Hafer said of the bird as it drew out half a sardine and gulped it back. “He chases all the other birds away, so I let him have a little bit.”

Like every other independent-business owner who relies on nature for income, Hafer and his fellow California fishermen face more challenges with each passing year. Labor is expensive and hard to come by; new restrictions on drift nets and crab traps make fishing more challenging, if safer for marine mammals. In marine protected areas, set aside by federal and state authorities to limit human activities, fishing is forbidden near certain prime reefs; Chinook-salmon runs have dwindled as global temperatures rise and inland rivers dry up.

To hear Hafer tell it, offshore wind could finally push commercial fishing past the point of rescue. The 65-year-old worries that when offshore wind turbines come to California for the first time, it will mean the end of not just his income but a way of life. It doesn’t matter that the turbines will float on the water’s surface, he said; any new ocean technology means trouble. “They’ve never done this on this coast before,” Hafer said. “And they don’t seem to care anything about fishermen.”

Hafer is half Italian and half German, and has the look of a man who has spent his life on the sea—his graying hair is curly and wild, his nose an ashen red from the sun. As the president of the Morro Bay Commercial Fishermen’s Organization, he is the fisherman others defer to when you ask them about state regulations. The species he and his fellow fishermen harvest—rockfish, Dungeness crab, black cod—are the kinds of fish that show up in the “best” or “good” columns on the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s fish list. The sustainability of these fisheries is due in part to laws that impose tight quotas and require stringent permits. But local and sustainable is also what California diners demand and will pay for: A pound of live rockfish can net a fisherman a wholesale price of $10. Once you remove the fish’s head, bones, and eyeballs, the edible protein that’s left is worth three or four times that much.

Even some fishermen think their product is overpriced. “Some of the stuff we’re catching is becoming elitist,” said Mark Tognazzini, another Morro Bay fisherman, who also runs a harborside restaurant. He considers it unfair that less wealthy Californians are limited to farmed tilapia and cheap imported shrimp. “People have to be able to afford to eat our fish or they’re not going to support our fishermen. If they’re not eating what we’re catching, why should you ask them to come up and speak on your behalf at a City Council meeting?”

Tognazzini agrees with Hafer that when the offshore wind industry comes to Morro Bay, the local catch could become rarer than ever. “I’m worried that some of this stuff is going to get fast-tracked and not looked at as carefully as it should be,” he told me. “When they regulate fishermen, they err on the side of caution.” When they regulate industry, they follow the money.

“I’m worried,” Tognazzini said, “they’re going to just sell the ocean to the highest bidder.”

Hafer is right that Pacific Ocean wind development could be an economic powerhouse. A study from the Schwarzenegger Institute at the University of Southern California estimates that developing 9 gigawatts of offshore wind would support an average of 38,000 construction jobs annually over a five-year period, and that 10 gigawatts of wind power could add as many as 4,500 permanent operation and maintenance positions that would last the lifetime of the plants. Ten gigawatts is only what California needs in offshore wind energy to hit 100 percent clean energy by 2045; hundreds more could be harvested from the ocean wind over time. By 2040, the gross output of California offshore wind could be worth as much as $31 billion.

Hafer isn’t convinced that so much clean energy is necessary. In our first conversation on the phone, he told me he wasn’t even sure the climate was changing. Yes, he had noticed that the ocean is warming, but he attributed that to a chain of southern Pacific volcanoes spewing hot lava beneath the sea. In person, he backed down a little. “I think the seasons over the years have moved,” he allowed. He just doesn’t consider it an emergency.

The latest and grimmest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that massive, immediate investments in clean energy and infrastructure are needed to keep the planet habitable for humans. But Hafer can’t let go of the idea that the urgency of climate change is an “excuse” for profit-mad corporations to occupy the waters off Morro Bay. “They’re all gung ho on doing this,” he told me. “It’s like a stampede. They’re like, ‘Well, climate change is more important than the whales and the fish and everything else in the ocean. We have to get these [wind turbines] in because climate change is an existential threat to our lives.’ And I just don’t see it that way.”

It is true that renewable-energy development too often comes at the expense of the very habitats we’re trying to preserve. To me, Hafer sounded a lot like the environmental activists in California and Nevada who claim that desert tortoises, which die off in heartbreaking numbers after being relocated for the development of gargantuan solar farms, are paying the price of human overconsumption. We don’t need to generate more electricity, these activists say; we need to use less.

Tognazzini, who doesn’t dispute the science of global warming, sympathizes with this view. “We do some stupid stuff,” he said. “We catch squid in California and send it to China for processing, and then it comes back and we eat it.” Conservation, he told me, “is one of those simple things we’ve gotten away from as a society.”

Without explicitly saying so, Hafer and Tognazzini are advocating economic degrowth as a climate-stabilization strategy. But if the timescale of renewable-energy development makes you contemplate your mortality, try thinking about the political will and time it would take to deliberately slow the global economy. Tognazzini does recognize that “wind and solar is the technology we’ve got” to avert climate catastrophe. “And there’s never a perfect place to put it,” he acknowledged. “I think a certain amount has to be seen as kind of an acceptable evil. But where does it end?”

Put another way, how much wind is worth how many fish? And how many whales have to die to save the climate?

Weinstein insists that the answer is none. Large drilling rigs have been operating on floating platforms in oceans around the world for decades, she said, “and there isn’t one whale known to anybody that got tangled up in oil-platform mooring lines. It just doesn’t happen.”

As I talked with the fishermen, and watched their comments accrue in the chats during public Zoom meetings, I sensed that they see themselves in a constant, frustrating struggle to educate the developers and rule makers about the marine environment they know so well. The people putting in bids and making decisions, they say, can’t possibly be relied on to protect the long-term health of a fishery, or the future of migrating whales.

This is the kind of distrust and misunderstanding that Crow White is hoping to resolve. For the past three years, White, an associate professor of coastal marine science at the California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, has been working with a team of researchers and students on what he calls a “trade-off analysis” of the Central Coast’s waters, evaluating each segment of the ocean for its value in energy, in fish, and in seabird habitat. To analyze the potential trade-offs between floating offshore wind turbines and fisheries, for instance, team members look at “fish tickets”—the catch reports fishermen submit to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Then they compare the value of that catch with the potential value of wind energy in a certain piece of the ocean as calculated by one of White’s colleagues, the atmospheric scientist Yi-Hui Wang. In this way, they can begin to identify which areas of the ocean will yield the highest value in wind energy with the least damage to the ecosystem.

Trade-off analysis is simple when you’re comparing just two interests. “Then it’s just kind of a ratio,” White told me. “Then you can say, ‘Wind energy high, fisheries impact low.’” In that instance, you’re comparing metric tons of catch with potential megawatts of power, as well as the value of the energy based on demand and time of day. “The trade-off,” White explained, “is represented in dollars and tons.” With seabirds and whales, you need a different metric, based on “the probability of population decline due to the wind farm.”

But figuring out that percentage isn’t easy, White said. Nor is it simple to quantify the “viewshed,” a value dismissed by some climate hawks as the shibboleth of coastal NIMBYs, but not by White. “People don’t like to look out on the ocean and see a bunch of blinking lights” from wind turbines, he said. “It’s a blemish to the viewshed, and it affects people’s enjoyment of the ocean.” Those views, he noted, have a spiritual value for some people. “As a surfer,” he said, “I totally get that, and agree with it.”

Five years ago, White led a study in which he used similar methods to limit the number of coastal residents who’d be disturbed by the blinking lights of an aquaculture farm in the ocean off Southern California. White and his colleagues created a terrain map of the coastline, combined that with data on population density, and “basically summed up the number of eyeballs that can see one of these blinking lights.”

White and his collaborators are currently updating a study of California coastal fisheries, using both fish tickets and “vessel-monitoring system” data, from which the researchers can infer how long a boat stayed in one area, presumably catching fish. None of the data are perfect—fish tickets are far from precise, and VMS data don’t explain why a boat is hanging out in a certain location. (Fishermen might pause because they’re catching fish, but they might also simply be drifting—eating a meal or repairing their nets.) But by merging the two data sets, the researchers believe they can come up with “a better estimate of fishing effort, landings, and value than has been produced along the California coast,” White said. Eventually, he and other researchers want to do the same for seabirds, whales, and yes, even viewsheds.

White recognizes Hafer’s concern about the effects of cumulative pressures on fisheries. “[Fishermen are] going to say, ‘You’re just adding more straw to the camel’s back, and you’re breaking us,’” White told me. It’s the same for whales and seabirds. “Birds have already taken a huge hit from all the things we’ve done to them,” White said. “In the oceans, [the insecticide] DDT is an example. And so to say, ‘Well, this wind farm is okay because most of the birds aren’t that far offshore’” is to ignore what conservationists are saying: “It’s death by 1,000 cuts. And you’re just doing a few more cuts.”

Floating wind in the Pacific Ocean is without a doubt a grand experiment, and no trade-off analysis can make it otherwise. Nor can the analysis eliminate wind’s footprint. “You’re never going to have green power from wind farms off our shore and have no impact on anything else,” White said. “Our objective is just to make the impact as low as can be relative to the power production.” Because we need the power. But we’d also like to have the fish.

One afternoon on the way back from a trip north, I stopped in Morro Bay to have lunch at Mark Tognazzini’s Dockside restaurant, which has an outdoor deck that looks out at Morro Rock, the landmark feature of Morro Bay. I had rockfish on a bed of rice; the fish was delicate and flaky and had a fresh, buttery flavor that reminded me of fish I’d caught myself, mostly in Minnesota lakes. I thought about what Tognazzini had told me, that he worried not just about wind farms, but about the whole future of independent commercial fishing.

And it’s not just fishermen threatened by corporate monopolies, he said. It’s all small food producers—the cattle guy, the tomato guy, the family with a handful of dairy cows. He sees all of them going the same way, even as well-meaning consumers frequent farmers’ markets; when the pandemic closed the markets, some Californians went so far as to buy fish directly from fishermen on their boats. “Corporate America is starting to own the ocean,” Tognazzini lamented. “It’s not going to be the small guy going out and catching a couple hundred salmon to sell on the open market. That’s going to go away.”

Tognazzini isn’t so concerned about how offshore wind will diminish his income. He’s sure that Castle Wind, or any wind company that moves forward with its plans, can compensate the fishing community for any losses, just as the telecommunications companies did when they laid fiber-optic cables through Morro Bay. Castle Wind is already currying favor with the locals, he said: “Before COVID,” he told me, “they sponsored our Harbor Festival.”

“Fishermen may be made whole” when the wind farms move in, Tognazzini said. “Maybe wholer than they should be.” Castle Wind has drawn up a mutual-benefits agreement with the Morro Bay Commercial Fishermen’s Organization that promises to pay fishermen for lost catches and unforeseen impacts; the precise dollar figure will vary contingent upon energy generation. With sufficient compensation, some fishermen could conceivably sell their boats and retire early. “But that’s just for this generation,” said Tognazzini, who is 67. “What about the generation coming up behind us?” As anyone who attends a meeting of fishermen and state agencies can discern, the fleet of current permit holders is mostly an aging bunch, graybeards with sun-ravaged faces and gravelly voices who make Tom Hafer look fresh-faced in comparison. Most will likely move on within the next decade. If wind companies compensate those fishermen for the impact of the wind farms, “do they also take care of the next generation?” Tognazzini asked. “The people who might have been planning to fish here, or might like to fish here, but can’t?”

And then, he wants to know, “what happens to the infrastructure underneath the fishermen? The restaurants, the fish markets, the fish buyers, the fuel dock, the ice stall that sells ice or the grocery store that sells groceries to the fishermen—all that infrastructure suffers when fishing suffers.” And if the fishing goes away, what happens to the town and culture of Morro Bay?

“We might be the last of the small-boat independent commercial fishermen left on the West Coast,” Tognazzini said. “I really don’t want to be the one to catch the last fish.”

If offshore wind is done right, its boosters say, he won’t be. If it isn’t, everybody loses—including the wind industry itself.

In California, a tangle of different agencies are involved in the effort to install the maximum amount of offshore wind power with the minimum number of conflicts. California Fish and Wildlife looks after the fisheries, whales, and seabirds; the California Coastal Commission reviews offshore development to make sure it follows state environmental law. The California Energy Commission makes the plans and policies that will transition the state to clean electricity; the State Lands Commission will sign off on the locations of onshore transmission cables.

Before President Joe Biden took office, “wind was something we were all doing a little bit of work on,” Mark Gold, the executive director of the state’s Ocean Protection Council, told me. Commissioner Karen Douglas of the California Energy Commission started conducting workshops in 2017 with fishermen and others who might be affected by offshore wind. “We thought we were ahead of the game,” Gold said. After January 20, 2021, “all of a sudden it got turbocharged, and it felt like we were running behind.” After that, high-level officials started meeting at least once a week. “And it’s been maintained the entire time,” Gold said. He can’t recall such energetic collaboration on any other issue since he joined the agency two years ago.

“This is not,” he said, “something anyone is taking lightly.”

Gold, who also serves on the Coastal Commission, has been a major force in California environmental policy making since the late 1980s. He is known for his scientific rigor, and he sounded positively sanguine about California’s plans for offshore wind. He has already seen state and federal plans change as new data come in, he told me. “The boundaries of the call areas are much more palatable from an environmental perspective than how we thought they might have been a year ago,” he said. “That was pretty cool to see.” Of the $20 million that has been added to the state budget to jump-start offshore wind energy, $2.1 million will go to the Ocean Protection Council to facilitate research on potential impact to fisheries, marine life, and cultural resources, to make sure state agencies have the best available information. “We’re not relying on the feds,” he said, even though BOEM is dictating the time frame.

That time frame is either impressively ambitious or ridiculously so. The Biden administration has called for 30 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity to be installed by 2030, equivalent to about 20 or 30 decently sized coal-fired power plants. Currently only two conventional offshore wind projects off the coasts of Rhode Island and Virginia send a tiny amount of electricity to nearby communities. But now 18 sizable projects are in the offshore wind pipeline, including the Vineyard Wind, which the federal government signed off on in May.

Nine years isn’t much time to accomplish what amounts to a transformation of the U.S. grid. All the more reason, Gold said, for state agencies to resolve objections promptly and to the satisfaction of the greatest possible number of stakeholders.

“We want to do this,” he said, “in a way that sets the standard for the rest of the world.”

This Atlantic Planet story was supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.