South Sudan and the betrayal of Christian campaigners

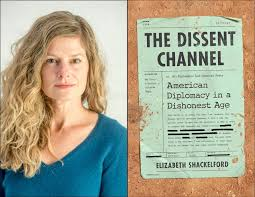

Christian activists around the world played a vital role in the creation of the world's newest nation, South Sudan, in 2011. A new book, The Dissent Channel by Elizabeth Shackleford, explains how the hopes of global peace campaigners and the optimism of diplomats has come to naught. Shackleford, a former foreign service officer at the US embassy in the capital, Juba, witnessed the destruction of the dream by corrupt rebel leaders-turned-politicians. Her page-turning account of the war adds a human voice to numerous depressing reports produced by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and the Enough project.

In 2013, only two years after independence from the brutal Islamist dictators in Sudan, South Sudan's leaders launched an ethnic cleansing campaign against their traditional foes that continues to this day. As many as 400,000 civilians (out of a population of 10 million) are thought to have died. Millions more have fled the fighting and are now dependent on the international community for food and shelter.

For decades, Christians in Europe and North America protested against the jihadist policies of the Khartoum regime, drawing the world's attention to the slaughter of non-Arab Sudanese by the Sudan government, the destruction of churches, and the enslavement of Christians. The UN estimates two million southern Sudanese died in their struggle for independence. The US, Britain and Norway, lobbied by their Christian activists, became the midwives of a peace process culminating in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement of 2005. Following a referendum, South Sudan gained its independence in 2011.

At the time, some of us warned that the historic mutual suspicion between the Dinka and Nuer ethnic groups might re-emerge. Billions of dollars of overseas aid poured into South Sudan, unaccounted for, as rebel leaders proved ill-prepared to run ministries. There was no attempt to diversify the economy away from oil, or to encourage South Sudanese to grow their own food, rather than relying on imports from neighbouring Uganda.

Shackleford's book begins as she is posted to the US embassy in Juba a few months before the country disintegrated into violence. She was soon worried by the way in which the US (South Sudan's most generous sponsor) pandered to the president, Salva Kiir. She concluded that America had invested so much money and diplomatic credibility in the new country that it was reluctant to confront the many warning signs: the kleptomania of its leaders, media restrictions, the harassment of UN and US officials, the imprisonment and torture of local critics, and the exclusion of ethnic rivals.

Even when UN staff were beaten by the Presidential guard, the US was loath to challenge Kiir. Instead, diplomats faced daily humiliation by Juba officials who wouldn't return their calls, and attacked America's "neo-colonialism" whenever questions were asked about the missing billions of aid.

On one occasion, South Sudanese soldiers invaded a compound frequented by foreign aid workers, gang raped the women and killed a journalist. Throughout the attack, as the Americans under siege pleaded with the US embassy to send help, their country's diplomats asked the South Sudan government to send soldiers to deal with the problem - even though they knew it was South Sudanese soldiers responsible for the violence. The UN peacekeeping mission also refused to send help for fear of offending the Juba government.

As South Sudanese officials openly incited violence against foreigners, the diplomatic community remained in denial. Even as war broke out, and Kiir's Dinka soldiers ethnically cleansed the country of Nuer civilians and other minorities, diplomats accepted Kiir's groundless claim that the Nuer leader, Riek Machar, had started the fighting.

The US subsequently spent more than $17 million housing Kiir, Machar and their followers in luxury hotels in Addis Ababa during endless peace talks, always putting the most optimistic spin on the fruitless negotiations. Multiple peace deals later, the suffering of the South Sudanese people continues. Notable, the relentless reconciliation work of local Christian groups has been one of the few bright spots in an otherwise dismal situation.

Shackleford's book is a damning chronicle of the naivety and gullibility of Western governments. Rather than making good on their expressions of concern, they continued to pour money into South Sudan.

President Obama and his advisor, Susan Rice, were unprepared to revise their view that Salva Kiir was "their man." Shackleford concludes that Kiir was, and is, empowered to continue his reckless behaviour with impunity because he knew that the international community would never make him face any consequences. It should be noted that Susan Rice is among the candidates Joe Biden is considering as his vice-presidential nominee.