We can take a better approach than what was put forth in the failed “Compassion Seattle” City Charter Amendment.

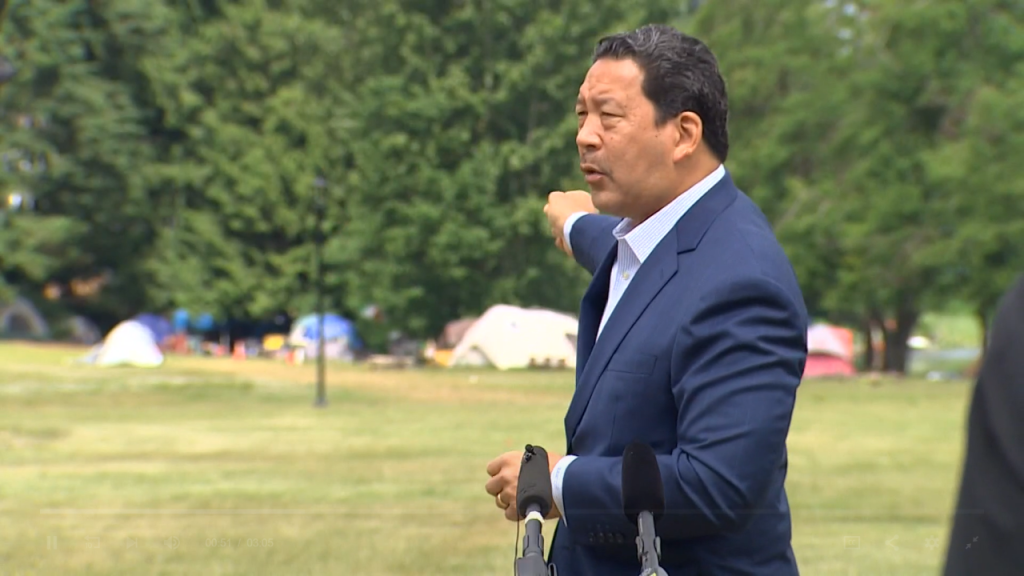

City Charter Amendment 29, posed by “Compassion Seattle” is dead, at least formally. Bruce Harrell seems intent on screaming “long live the Charter Amendment!” by making it into mayoral policy. In fact, his promise to sweep encampments and punish those who won’t go into shelters suggests for some Seattle “centrists,” CA29 was never about housing or compassion at all, but about shoving homeless Seattleites out of sight so we don’t have to be confronted by the ugliness of inequality in our city.

Still, CA29 was quite popular, a poll suggesting 61% of Seattle residents in favor. But in favor of what, exactly? The text was sprawling and ambiguous, with very little agreement on what the amendment would actually accomplish. For many, the promise of quickly building 2,000 units of housing, plus requirements restricting park removals to situations where real housing is on offer, was attractive. But in the end, the text contained too many trojan horses and the Harrell campaign looked likely to use too many of them as a pretext for sweeping parks.

With CA29 dead, but the mayoral race heating up, it’s worth asking: what would a set of policies that are genuinely compassionate and effective look like going forward? Here are nine steps.

- Get real buy-in from homelessness experts. Early on, the campaign backers claimed that many human services organizations, like DESC, Plymouth Housing, Fare Start, the Public Defender Association and Evergreen Treatment services endorsed the measure. This turned out to be false. Instead, many are a part of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, which sued to stop CA29 from going on the ballot. Organizations with expertise and people with lived experience need to be at the center of these conversations.

- Build affordable housing that is actual housing, fast. CA29 required 2,000 units to get built in a year. This sounded great, but then it included a trojan horse that allowed a bed in a big open room to count as housing. We know congregate shelter is often unhealthier, less hospitable, and more dangerous to our unhoused neighbors than are tents in parks. This is not compassionate; it’s just a cheaper way to empty the parks. This was a deal-killer. These should have been permanent supportive housing units for the chronically homeless.

- Build enough housing for all people chronically experiencing homelessness. King County’s point-in-time count suggests at least 3,355 people suffer from chronic homelessness. This is our highest-needs population, and they need housing now.

- Expand to housing for the episodically homeless. Many people who are homeless need help for shorter or more medium length periods of time. When you consider the 4,000 people living in shelters, or our other 3,600 rough sleeping neighbors in King County, Seattle needs to shoulder housing for at least 5,000 of them. That is to say nothing of the tens of thousands of units we need to end the housing affordability crisis.

- Fund behavioral health support for all at-risk populations. CA29 required “low-barrier, rapid-access, mental health and substance use disorder treatment and services . . . [for the] chronically homeless” with a “behavioral health rapid-response field capacity” that worked with “non-law enforcement crisis response systems,” using “culturally distinct approaches.” This was to be available to everyone living in housing for the otherwise homeless. It should also include the recently homeless or others who are at high risk of losing their homes as well. (We should have fully funded social medicine with complete behavioral support. But I will limit my scope to homelessness for now.) We should also be clear not to insinuate that homelessness is primarily about mental health or substance abuse, a favorite conservative canard. An overwhelming supermajority of unhoused people are mentally fit, just as a lopsided majority of folks with behavioral or substance abuse problems have housing. That being said, this population does suffer from somewhat higher rates of severe behavioral problems and mental illnesses, in part because homelessness exposes them to much more trauma. More at-risk people should be able to receive this support.

- Tie eligibility for future contracts to performance. CA29 also mandated that the city publish quarterly information regarding the “effectiveness of strategies and services designed to transition homeless individuals to housing,” and inform the public “which city services, activities, and practices may contribute to people entering or experiencing homelessness.” While some say sunshine is the best disinfectant, I say the city already measures the impact of the providers who serve the homeless and it doesn’t work. Some of the providers that flunk just go straight to the city council and get written directly into the budget instead. Data dashboards don’t necessarily prevent cronyism or incompetence. Tying funding to performance would work much better. Organizations should be given contracts only if they are high-performing. Performance should be measured by the ratio of dollars spent to months housed, with a minimum magnitude for average months housed. This should be measured separately by risk tier, since chronically unsheltered folks are much more expensive to house. Racial groups and other marginalized groups should also be measured separately. Efficiency should be maximized for interventions within the groups, not across the groups, to prevent performance data from driving biased funding away from marginalized citizens.

- Reduce the cost and time to build housing for the homeless. CA29 required the City to waive land use codes, regulation and permitting fees, move projects serving the homeless to the front of the permitting line, and refund various city-related costs, fees and sales taxes. This was welcome, but it could have been better. These changes should be permanent, to not only help us get out of this emergency, but prevent future ones, and should include all subsidized housing. We must also waive the design review process for all affordable housing, as well as all parking lot coverage, and rear and side setback requirements. Finally, we need to increase heights for affordable housing to 85 feet in multifamily and mixed-use neighborhoods, and 45 feet in lower density neighborhoods, with increased floor-to-area ratios to match. At minimum, this should apply in all high opportunity and high frequency transit neighborhoods, and to community land trusts in remaining neighborhoods.

- Fund it using progressive revenue. CA29 was an unfunded mandate. We cannot house over ten thousand homeless people, nor prevent floods of future Seattleites from losing shelter, without building many thousands of units of housing. Real units are expensive. Simple math and chronic inaction show that nothing in our current budget could come close to the cost of building them. It doesn’t do us any good to pretend. McKinsey, not exactly the most progressive organization on earth, says King County needs to spend between $450 million and $1.1 billion a year in incremental public funding on subsidized housing just to stabilize housing for rent burdened, extremely low income people.

- Legislation on camp removals should offer clear and limited criteria for any kind of removals. Sweeps without housing on offer are cruel and unusual punishment, according to the Ninth Circuit court in Idaho. [The Supreme Court declined to hear the case, allowing the decision to stand.] That holding does, however, allow people to be swept into shelter. But Seattle can do better than the bare minimum required by the conservative Court. Given what we know about beds in congregate shelters, we can comfortably say, they aren’t housing. Shelters offer no privacy, very little safety, and extremely little autonomy. They often require sobriety, which is completely out of step with current housing-first best practice. They may force people to throw away their things, separate from partners or family members, or get rid of their pets. And shelter may expose them to assault or trauma. This is not a compassionate alternative, and it is not housing. Forcing people into these congregate shelters should easily meet our definition of cruel and unusual. We cannot do so and respect the dignity of humans living outside our doors.

Legislation on removals should offer clear and limited criteria for any kind of removals. CA29 did have some good language requiring individualized interventions that paid attention to culture, family structure, and disability. It also acknowledged the possibility of harm from encampment closures. It should explicitly give the aggrieved simple administrative grounds to challenge the manner in which removals take place, to have harm redressed, and it should put transparency and accountability mechanisms in place.

It should also limit when removals can take place. Real housing, not fake congregate housing, should be on offer. Otherwise, removals should be limited to public health risks, real threats to public safety, or blocked access to major public goods, not counting the land itself that is being occupied.

While CA29 is dead, these policy questions live on. Hopefully our region can come together, this time around something genuinely compassionate and genuinely effective.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated the Supreme Court affirmed the Ninth Court’s Martin v Boise ruling. By declining to hear the case, the Supreme Court let the lower court ruling stand, which is legally distinct from affirming that ruling.

Ron Davis (Guest Contributor)

Ron Davis is a consultant that helps early stage companies take new technologies to market, specifically, products and services that improve the world for workers and citizens. He's on the boards of Futurewise, Seattle Subway, the Roosevelt Neighborhood association and the University YMCA, where he fights to make Seattle a more just, inclusive, green, walkable, city. He has a JD from Harvard Law School and lives in Northeast Seattle with his wife, a family physician, and their two boys.