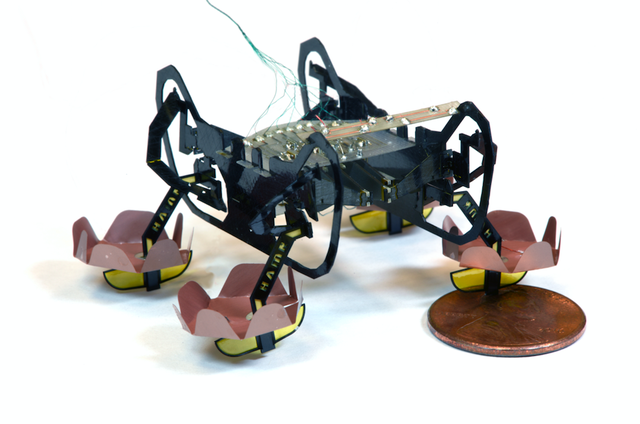

Small wonder that scientists want to copy the cockroach, one of the most durable creatures around. But Harvard roboticists are now one-upping the insect with Harvard's Ambulatory Microbot (HAMR). The new, next-generation HAMR can walk on land, swim on the surface of water, and walk underwater for as long as needed.

What gives HAMR its terrain flexibility are the multifunctional feet, made of electrowetting pads (EWP). The focus of electrowetting is reducing the surface tension in a liquid/solid interaction via electricity. That is, an electric charge makes it easier for materials to break a water surface.

With its electrowetting pads submerged and activated, the HAMR can move across the surface of the water. With four pairs of asymmetric flaps and custom-built swimming gaits, the HAMR paddles in a manner that's similar to a diving beetle.

“HAMR’s size is key to its performance. If it were much bigger, it would be challenging to support the robot with surface tension and if it were much smaller, the robot might not be able to generate enough force to break it,” says Neel Doshi, a Harvard grad student and co-author of the paper describing the new HAMR capabilities, in a press statement.

Indeed, the HAMR only weighs 1.65 grams, which about the same as a large paper clip. It can carry up to 1.44 grams on its back before it will drown.

One of the biggest challenges for the engineers was getting the HAMR to move from walking underwater to the surface again. The problem was the water tension, which would weigh down on the tiny HAMR with a force twice its weight.

The solution came from stiffening the robot’s transmission and installing soft pads on the robot’s front legs. The new pads allowed for friction redistribution. All of that allowed HAMR, when walking slowly up a small underwater incline, to break through the surface and walk onto dry land.

“This robot nicely illustrates some of the challenges and opportunities with small-scale robots. Shrinking brings opportunities for increased mobility – such as walking on the surface of water – but also challenges since the forces that we take for granted at larger scales can start to dominate at the size of an insect,” says senior author Robert Wood.

Researchers often look to smaller animals for inspiration. Harvard's neighbor, MIT, recently developed a robotic fish that can blend in with the real thing in order to better study the patterns of schools. But even if scientists can improve on the cockroach's ability to only walk 30 minutes underwater, they're still struggling to capture the other remarkable abilities of the tiniest creatures.

Source: Harvard

David Grossman is a staff writer for PopularMechanics.com. He's previously written for The Verge, Rolling Stone, The New Republic and several other publications. He's based out of Brooklyn.