Data courtesy Coalition for the Homeless

Race of heads of households in the New York City shelter system.Rhonda Jackson never really thought about becoming homeless until, one day, she was.

Jackson and her children were living with her grandmother, who she cared for in the family’s Springfield Gardens home. But when her grandmother died, Jackson and her kids were left without a home. It was a shock to Jackson, now 59 and living in an apartment in Williamsburg that she secured through an affordable housing lottery.

“I grew up with the best things in life that my family could get me,” she says. “Most people don’t think about homelessness or being homeless until it directly affects them. I didn’t.”

Still fewer think about what it means to not be homeless, Jackson says.

A sea of factors

A simple question, “Why aren’t you homeless?” forces us to consider a complicated, and often unexamined, set of personal circumstances — from our own personal safety nets to our favored identities within deeply unjust and racist social structures

Those inequities present opportunities for some, especially White men, while creating obstacles for others, like families headed by single Black and Latino mothers, who account for the vast majority of New York City’s Department of Homeless shelter population.

There are the unearned and uncontemplated privileges that inoculate us from homelessness, even during an historic homelessness crisis, likely to worsen as a consequence of the COVID-19 economic fallout.

Steady jobs, financial savings and assets, home equity, good credit, higher education and dual income families all enable us to maintain housing. Never been to prison? That will help you find and maintain a home, too. Formerly incarcerated individuals are nearly 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than people who have never been incarcerated, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

Stable mental health is an important factor, but many people with serious mental illness maintain their housing as well — it helps when they have access to consistent treatment and a support network that helps them manage their mental health issues.

Education can go a long way toward getting a job and maintaining a home — as long as you earn a steady income, pay off your loan debt and manage other issues in your life. A study by the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless found that 20 percent of the city’s homeless adults had college experience. Meanwhile, many people experience homelessness while they attend school, including nearly 20 percent of community college students nationwide, according to CUNY’s HOPE Center. Fourteen percent of CUNY students are homeless, while 55 percent have experienced housing insecurity, the university system reports.

There are natural gifts and above-average skills that allow some people to shine while others struggle. But there is also a heavy dose of good fortune and timely intervention along the way.

And there are the health disparities and deep divides in access to consistent, quality treatment that fuel poverty and force people from their homes

A near-total lack of affordable housing in New York City, where 44 percent of residents spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, certainly fuels the homelessness crisis. At the same time, race is inextricably linked to each one of these inequities, which can determine who has housing and who doesn’t.

“Systemic barriers to employment and education, health and social determinants of health, you cannot simply disaggregate race from any of those items,” says Raysa S. Rodriguez, the associate executive director for policy at the Citizens’ Committee for Children. “COVID has helped us see quite clearly how health, income and race are all tied together.”

The key factors: Generational wealth and race

Perhaps no factor is more likely to predict one’s ability to maintain stable housing than generational wealth, a factor deeply tied to race.

“Wealth provides individuals and families with financial agency and choice; it provides economic security to take risks and shields against the risk of economic loss,” write the authors of a 2018 report published by the Duke University Center for Social Equity. “Literally, it takes wealth to make wealth.”

Blacks “largely have been excluded from intergenerational access to capital and finance,” the report continues, citing racist redlining and housing covenants, hiring practices, deed theft, exploitation and straight up segregation that have for centuries eroded the ability of Black families to earn and save money.

Not so for White families, who do not face structural obstacles to accumulating wealth and passing it on to future generations.

“I am not homeless, because I was born into a middle-class family, who owned land, to parents that had access to stable employment where they were paid a livable wage,” says Jamie Powlovich-Molina, executive director of the New York City Coalition for Homeless Youth.

“I am not homeless because I have never had a landlord refuse to rent to me and my daughter because of the color of my skin,” Powlovich-Molina continues. “Because I am a straight, cisgender White woman who has many privileges that protect me from the racist, discriminatory housing systems that were intentionally created to make sure that people with my privileges are less likely to be homeless.”

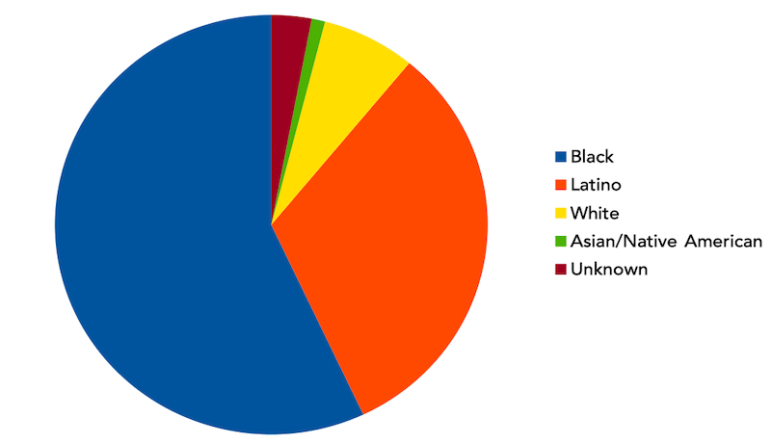

The racial disparities are evident in New York City’s DHS shelter system, where about 57 percent of heads of household are Black, 32 percent are Latino, 7 percent are white and 1 percent are Asian American or Native American, according to the Coalition for the Homeless.

“When you think about family homelessness in New York City in particular, we need to look at race and systemic inequities that allow for a disproportionate number of Black and brown households to endure housing instability,” says Rodriguez, of CCC.

“Those are identities that I share. It very well could have been me and it hits close to home,” she adds. “However, I recognize the privilege I have gained with a career and education trajectory that allows me to have resources that protect me from the housing instability that so many New Yorkers from communities I call my own face due to system barriers.”

Motherhood, color and risk

In recent years, Jackson, the formerly homeless woman now living in Williamsburg, has considered the factors that forced her into precarious living situations and the city shelter system. She has also reflected on developments that enabled her to finally secure a permanent place to live.

Raising her kids alone following a divorce was the main reason she could no longer afford her rent, she says.

“Women of color like me, single moms, we can’t work enough to pay for more than one child,” she says.

She’s not alone: About 70 percent of city shelter residents are families with children, with the vast majority of those families headed by single mothers, according to the Department of Homeless Services. On July 7, a total of 18,926 children of all ages slept in a city shelter, according to the agency’s most recent daily census report.

About 15,000 school-aged children — kids between ages 4 and 17 — stay in city shelters each night, DHS said in December 2019. They account for a fraction of the 114,000 schoolchildren who experienced homelessness at some point during the 2018-2019 school year, according to state data.

Kadisha Davis can relate. When Davis was eight months pregnant, her landlord kicked her out of the apartment she rented in Laurelton. The property owner didn’t want a newborn in the building and recruited family members to harass Davis until she left, she says. Her then-husband was living in another country and unable to pitch in, she says.

“I didn’t have help from my family and I wasn’t working because I was pregnant and I was on maternity leave. You shouldn’t put an eight-months-pregnant woman on the street” she says. “From my experience, if I had the support I would not be homeless.”

Davis, on leave from her retail job, eventually found a room in a shared apartment in Crown Heights for her and her daughter, but another tenant’s bizarre behavior compelled her to move into the DHS shelter system.

After staying in four different shelters and receiving little help finding a permanent home, Davis says a chance meeting helped her secure an apartment.

A woman she encountered on the subway knew someone who worked in NYCHA admissions and agreed to review Davis’ four-year-old application. Later that year, Davis was approved for a 10th-floor apartment in a Fort Greene NYCHA building.

“I had to take my destiny into my own hands and then I got some help,” she says. She now counsels other people experiencing homelessness and provides support through her YouTube channel, which has more than 1,100 subscribers.

The impact LGBTQ identity

Many families are accepting of LGBTQ young people, or at the very least allow them to remain in their homes without bullying or harassing them.

Nevertheless, LGBTQ teenagers and young adults are twice as likely to experience homelessness as their peers, according to a 2018 report by the University of Chicago. As with other inequities, race is a clear factor in the likelihood of becoming homelessness.

Young people who are Black and LGBTQ experienced homelessness at twice the rate of white LGBTQ young people, the University of Chicago report finds.

People of color account for 90 percent of the city’s young LGBTQ homeless population, a coalition of service organizations wrote in a letter to the city in May. The organizations urged the city to restore funding for a novel jobs program for LGBTQ young adults, but the program did not make it into the new budget.

“I am not homeless, because I have never been rejected or ejected from my family because of how I identify or because of who I have chosen to be with,” says Powlovich, head of the Coalition for Homeless Youth.

Transgender New Yorkers face extreme discrimination, incuding bias among landlords that can lead directly to homelessness. Workplace bias often prevents transgender individuals from getting jobs or advancing in their workplace, meaning they can’t earn enough money to pay the rent.

Nationwide, more than 25 percent of transgender people report losing a job because of bias and more than 75 percent have experienced workplace discrimination, according to the National Center of Transgender Equality.

Health matters

Good health and quality insurance are all that separate some people, including people with solid incomes, from sinking under the weight of medical bills and losing their homes or apartments.

Health disparities prevalent among low-income New Yorkers further fuel homelessness. But so do unforeseen medical expenses for people with shoddy insurance or no coverage at all.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council says health problems, related expenses and the impact on employment are among the main drivers of homelessness, though they are often overlooked in macro-level discussions.

“An injury or illness can start out as a health condition, but quickly lead to an employment problem due to missing too much time from work; exhausting sick leave; and/or not being able to maintain a regular schedule or perform work functions,” NHCHC states in a fact sheet on the connection between health and homelessness.

Unemployment often means a loss of insurance, compounding the financial strain and plunging people into debt.

“In these situations, any available savings are quickly exhausted,” NHCHC continues. “Once these personal safety nets are exhausted, there are usually very few options available to help with health care or housing. Ultimately, poor health can lead to unemployment, poverty, and homelessness.

Davis says she knows people who have become homeless due to medical issues, and one friend who became homeless “overnight” because of a fire. The dual health and economic impacts of the coronavirus will only cause more stably housed New Yorkers to become homeless.

“I feel like anybody could become homeless at any moment, especially with COVID,” she says. “To be honest, anybody could become homeless.”

City Limits’ series on family homelessness in New York City is supported by Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York and The Family Homelessness Coalition. City Limits is solely responsible for the content and editorial direction.

2 thoughts on “Why You Aren’t Homeless: How Privilege & Fortune Shape the Shelter Census”

Parents upbringing. The lessons learned and valued taught by my parents. Do not spend your money foolishly . Learn the value of money. Go to work and HAVE GOALS. At age 61 retirement is completely stressless. I hate to admit this but it’s all about money. Unfortunately.

I have been homeless. Trust me it wasn’t about money. I married a man who turned out to be very abusive and self-centered. I had to take him to family court for an order of protection and finally to divorce him. For the nearly six months it took to escape to Ohio where my parents lived and go back and forth to family court, I lived with a girlfriend while my son lived with my parents. I also had to take my ex-husband to court to regain control of our apartment as well. I was a city worker and dues-paying, union member and so my lawyers were pretty much free. What I learned from the situation, be good to your friends, you never know when you’ll need them. Make better choices in the life partners you choose.