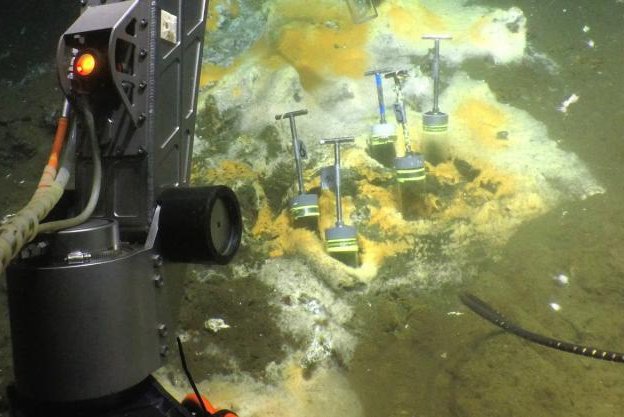

Scientists were able to collect microbial samples from hot vents at the bottom of the ocean using ALVIN, a deep-diving submersible. Photo by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

April 21 (UPI) -- Scientists in Germany have discovered a community of microbes that subsist on the ethane seeping from hot deep-sea vents at the bottom of the Gulf of California. They described their findings Tuesday in the journal mBio.

Different microbes can turn a variety of organic compounds into energy, but ethane consumption is rare. Most microbes can break down their preferred food source without assistance, but the breakdown of the two main components of natural gas, methane and ethane, requires cooperation between two different types of microbes, archaea and bacteria.

The cooperative pairing is known as a consortium. Because consortium microbes tend to reproduce very slowly, studying them in the lab is difficult. Scientists were surprised to find that ethane-munching microbes found at the bottom of Guaymas Basin are fast growers, with cells doubling every week.

"The laboratory cultures keep me pretty busy. But this way we now have enough biomass for extensive analyses," researcher Cedric Hahn, doctoral student at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, said in a news release. "For example, we were able to identify key intercellular intermediates in ethane degradation. Also, we present the first complete genome of a natural gas-degrading archaea in this study."

The bacteria from the newly discovered consortium are known species, but researchers had never seen the archaea species. They named the species Ethanoperedens thermophilum, meaning "heat-loving ethane-eater."

"We have found gene sequences of these archaea at many deep-sea vents. Now we finally understand their function," said researcher Katrin Knittle.

Scientists also found that the newly named archaea's close relatives eat CO2 and emit ethane. Researchers are now working to find out whether other consortium pairings can be manipulated to produce ethane instead of methane.

"We are not yet ready to understand all the steps involved in ethane degradation," said researcher Rafael Laso Pérez. "We are currently investigating how Ethanoperedens can work so efficiently. If we understand its tricks, we could culture new archaea in the lab that could be used to obtain resources that currently have to be extracted from natural gas."

It's possible consortium pairings cultured in the lab could be used to limit carbon emissions from various pollution sources.

"This is still a long way off," Wegener said. "But we are pursuing our research. One thing we know for sure: We shouldn't underestimate the smallest inhabitants of the sea!"