Shakespeare lived his life in plague-time. He was born in April 1564, a few months before an outbreak of bubonic plague swept across England and killed a quarter of the people in his hometown.

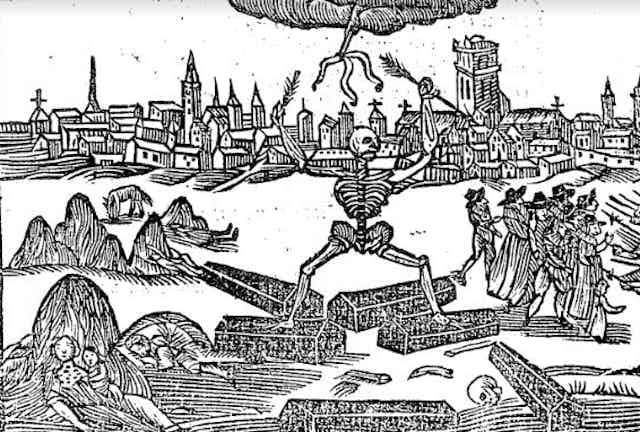

Death by plague was excruciating to suffer and ghastly to see. Ignorance about how disease spread could make plague seem like a punishment from an angry God or like the shattering of the whole world.

Plague laid waste to England and especially to the capital repeatedly during Shakespeare’s professional life — in 1592, again in 1603, and in 1606 and 1609.

Whenever deaths from the disease exceeded thirty per week, the London authorities closed the playhouses. Through the first decade of the new century, the playhouses must have been closed as often as they were open.

Epidemic disease was a feature of Shakespeare’s life. The plays he created often grew from an awareness about how precarious life can be in the face of contagion and social breakdown.

Juliet’s messenger quarantined

Except for Romeo and Juliet, plague is not in the action of Shakespeare’s plays, but it is everywhere in the language and in the ways the plays think about life. Olivia in Twelfth Night feels the burgeoning of love as if it were the onset of disease. “Even so quickly may one catch the plague,” she says.

In Romeo and Juliet, the letter about Juliet’s plan to pretend to have died does not reach Romeo because the messenger is forced into quarantine before he can complete his mission.

It is a fatal plot twist: Romeo kills himself in the tomb where his beloved lies seemingly dead. When Juliet wakes and finds Romeo dead, she kills herself too.

The darkest of the tragedies, King Lear, represents a sick world at the end of its days. “Thou art a boil,” Lear says to his daughter, Goneril, “A plague sore … In my corrupted blood.”

Those few characters left alive at the end, standing bereft in the midst of a shattered world, seem not unlike how many of us feel now in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

It’s good to know that we — I mean all of us across time — might find ourselves sometimes in “deep mire, where there is no standing,” in “deep waters, where the floods overflow me,” in the words of the biblical psalmist.

Poisonous looks

But Shakespeare can also show us a better way. Following the 1609 plague, Shakespeare gave his audience a strange, beautiful restorative tragicomedy called Cymbeline. The international Cymbeline Anthropocene Project, led by Randall Martin at the University of New Brunswick, and including theatre companies from Australia to Kazakhstan, envisions the play as a way to consider how to restore a liveable world today.

Cymbeline took Shakespeare’s playgoers into a world without plague, but one filled with the dangers of infection nonetheless. The play’s evil queen experiments with poisons on cats and dogs. She even sets out to poison her stepdaughter, the princess Imogen.

Infection also takes the form of slander, which passes virus-like from mouth to mouth. The principal target again is Imogen, framed by wicked lies against her virtue by a man named Giacomo that her banished husband, Posthumus, hears. From Italy, Posthumus sends orders to his man in Britain to assassinate his wife.

The world of the play is also defiled by evil-eye magic, where seeing something abominable can sicken people. The good doctor Cornelius counsels the queen that experimenting with poisons will “make hard your heart.”

“… Seeing these effects will be

Both noisome and infectious.”

Even being seen by antagonistic people can be toxic. When Imogen is saying farewell to her husband, she is mindful of the threat of other people’s evil looking, saying:

“You must be gone,

And I shall here abide the hourly shot

Of angry eyes.”

Pilgrims and good doctors

Shakespeare leads us from this courtly wasteland toward the renewal of a healthy world. It is an arduous pilgrimage. Imogen flees the court and finds her way into the mountains of ancient Wales. King Arthur, the mythical founder of Britain, was believed to be Welsh, so Imogen is going back to nature and also to where her family bloodline and the nation itself began.

Indeed her brothers, stolen from court in early childhood, have been raised in the wilds of Wales. She reunites with them, though neither she nor they know yet that they are the lost British princes.

The play seems to be gathering toward a resolution at this juncture, but there is still a long journey. Imogen must first survive, so to speak, her own death and the death of her husband.

She swallows what she thinks is medicine, not knowing it’s poison from the queen. Her brothers find her lifeless body and lay her beside the headless corpse of the villain Cloten.

Thanks to the good doctor, who substituted a sleeping potion for the queen’s poison, Imogen doesn’t die. She wakes from a death-like sleep to find herself beside what she thinks is the body of her husband.

Embracing bare life

Yet, with nothing to live for, Imogen still goes on living. Her embrace of bare life itself is the ground of wisdom and the step she must take to reach toward her own and others’ happiness.

She comes at last to a gathering of all the characters. Giacomo confesses how he lied about her. A parade of truth-telling cleanses the world of slander. Posthumus, who believes that Imogen has been killed on his order, confesses and begs for death. She, in disguise, runs to embrace him, but in his despair he strikes her down. It is as if she must die again. When she recovers consciousness, and it’s clear she will survive, and they are reunited, Imogen says:

“Why did you throw your wedded lady from you?

Think that you are upon a rock, and now

Throw me again.”

Posthumus replies:

“Hang there like fruit, my soul,

Till the tree die.”

A world cured

Imogen and Posthumus have learned that we come together in love only when the roots of our being grow deep into the natural world and only when we gain a full awareness that, in the course of time, we will die.

With that knowledge and in a world cured of poison, slander and the evil eye, the characters are free to look at each other eye to eye. The king himself directs out attention to how Imogen sees and is seen, saying:

“See,

Posthumus anchors upon Imogen,

And she, like harmless lightning, throws her eye

On him, her brothers, me, her master, hitting

Each object with a joy.”

We will continue to need good doctors now to protect us from harm. But we can also follow Imogen through how the experience of total loss can purge our fears, and learn with her how to start the journey back toward a healthy world.