Shannex staffers weren’t documenting wound care properly two months before Chrissy Dunnington was rushed to emergency in septic shock from a bedsore the size of a fist, a government inspection report reveals.

Health Department inspectors visited Parkstone Enhanced Living in Clayton Park Nov. 23 and 24, 2017 — two months before Dunnington was admitted to hospital.

“Upon a random review of resident charts, it was observed that wound care assessments and treatments were not consistently documented for residents with wounds. The assessment results were not consistently part of the residents’ care plan,” says the annual licensing inspection report obtained by The Chronicle Herald through a Freedom of Information request.

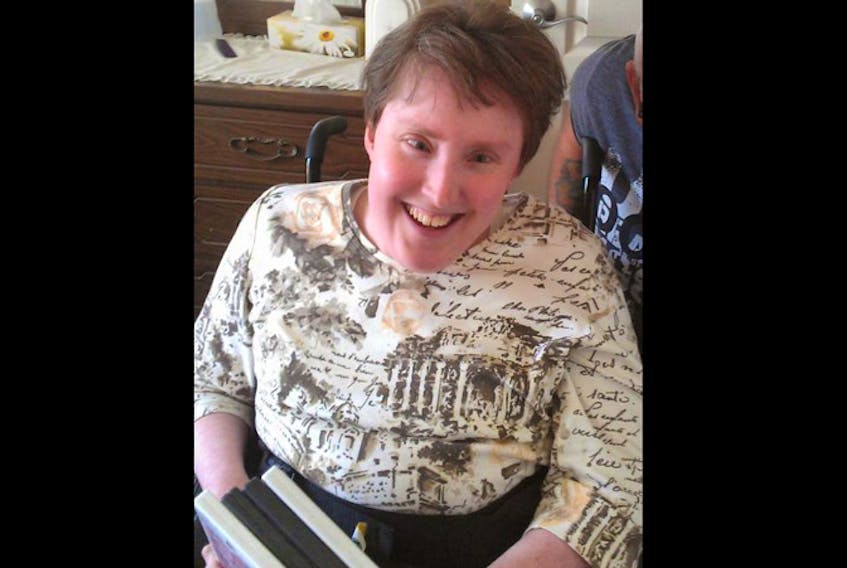

Halifax regional police are waiting for the medical examiner’s report before deciding whether to lay criminal negligence charges related to Dunnington’s death. The 40-year-old woman with spina bifida was a resident of Parkstone when she was rushed to hospital at the end of January 2018, in septic shock from an infected bedsore. Dunnington never recovered and died in March — a death her family believes was preventable.

It’s impossible to know if this non-compliance with sections 6.1.2 and 6.1.3 of the Long Term Care Program requirements influenced what happened to Dunnington. But the inspection report makes it clear that record-keeping around wound care wasn’t as it should have been at Parkstone.

Government inspection, promise

The requirement says “the licensee shall ensure ongoing assessments are completed in order to identify the unmet changing needs of the residents. Results of assessments are documented on the resident record, are communicated appropriately to staff, and become the basis for the resident plan of care.”

The inspectors that visited Parkstone nearly a year ago ordered the home owned by Shannex Inc. to provide a plan, with timelines, to fix the wound care documentation problem.

Inspectors found 11 other instances at Parkstone where requirements weren’t being met, including not documenting changes to urinary catheter appliances as per doctor’s orders. The report said Parkstone’s license would be renewed after it filed a plan at the end of December to make the necessary corrections.

Shannex officials had made some changes to its wound care policy in 2017. But after Dunnington’s story made headlines in May, CEO Jason Shannon introduced what he described as “a quality improvement program” to enhance changes already underway. The program stepped up reporting and monitoring of wounds to daily from weekly, and committed to “refreshed” wound care training for all front-line staff, as well as paying for specialized courses for two registered nurses.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Parkstone isn’t the only nursing home where inspectors discovered that bedsores, also known as pressure injuries, were not consistently reported on residents’ personal care plans.

During the five-month period covered by this Freedom of Information request, government inspection reports show the same deficiency was identified at Blomidon Court in Greenwich, Ryan Hall in Bridgewater, Harbourstone in Sydney, and Annapolis Royal Nursing Home. These homes each look after between 50 and 110 residents. At the home in Annapolis Royal owned by the MacLeod Group, inspectors also ordered that management repair aging and broken lifts used to transfer bed-ridden residents to chairs. Residents who aren’t turned or re-positioned frequently are at higher risk of developing bedsores.

This past summer, after a June spot survey revealed 152 “severe pressure injuries” and hundreds more minor wounds, the province promised to develop one standardized policy for long-term care homes.

That’s in the works. The province hired a team of six specialized nurses who spent two months helping frontline continuing care assistants and licensed practical nurses manage pressure injuries. And the government has appointed an expert panel to recommend what it should do to improve conditions for residents and staff.

Dorothy Dunnington, one of Chrissy’s sisters, met recently with the expert panel. She says her family suggested the panel consider the need for an independent agency to conduct licensing inspections and investigate complaints from residents or families.

“What good is an inspection if nothing ever changes and there are no repercussions?” Dorothy Dunnington said. “We also believe that the agency responsible for investigating these homes — both for regular inspections as well as complaints through the Protection for Persons In Care Act — should not be the Department of Health that so closely relies on these same homes.”

Meanwhile, until nursing home inspection reports in Nova Scotia are made routinely available to the public — something Health Minister Randy Delorey has committed to eventually do, though he hasn’t provided a timeline — it will be difficult to find out if the new initiatives lead to actual improvements in the prevention and treatment of bedsores.

RELATED: Long-term care reports reveal a strained and struggling system