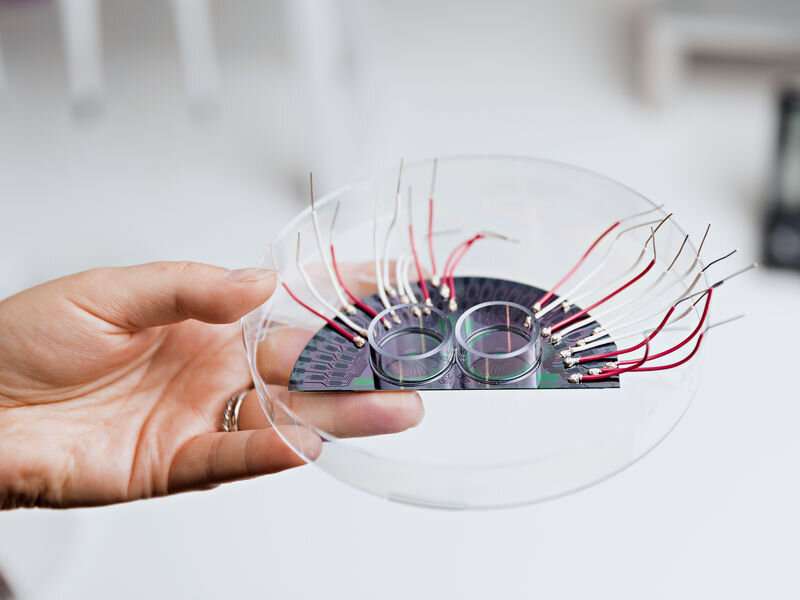

A tiny sensor that may play a significant role in the future treatment of illnesses

Academy of Finland Research Fellow Emilia Peltola holds in her hand a sensor that will play a significant role in the future treatment of illnesses. Many diseases, such as depression, chronic pain, Parkinson's and epilepsy are caused by neurotransmitter disorders. Among other things, neurotransmitters enable cells to communicate with each other. Problems in the production of these chemicals are the cause of symptoms like, for example, shaky hands in sufferers of Parkinson's disease.

Deep brain stimulation has achieved good results in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and epilepsy. The therapy involves electrically stimulating the patient's brain to produce neurotransmitters like dopamine. If a sensor were added to treatment devices installed in the brain, physicians would know in real time how the neurotransmitters were responding to treatment. Neurotransmitters are too small to be seen by the naked eye, and therefore no device can visualize us how they function directly, forcing us to employ other means to gather information.

"A definite benefit of such sensors would be the real-time nature of the data they produce. Neurotransmitters move from cell to cell very rapidly, and only a real-time method can let us know how much of a specific substance is present at each given moment. Treatments would become more effective and the risk of adverse effects would reduce," Peltola says.

Peltola is both a Doctor of Science in Technology and a medical researcher. A multidisciplinary background is an advantage in her work, which combines technology and biology. Funded by a grant from the Academy of Finland received in spring 2019 and funding from the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, she is searching for the optimal synthetic material for use in sensors, which measure neurotransmitters.

Toward new types of treatment

In addition to neurotransmitter concentration, it is important to know the location in which neurotransmitters are being released, how rapidly cells are releasing the substance as well as how long it takes for the cell to uptake it. Existing methods are unable to gather this information.

The part of the brain in which the sensor is placed determines which neurotransmitter should be measured. The functioning of glutamate, the neurotransmitter that affects learning and memory, is studied in the hippocampus in particular. Local measurements yield fresh information on disease mechanisms as well as on the functioning of the brain and pharmaceuticals.

Peltola believes that if measurements inside the body were to become possible, researchers could develop new diagnostic and treatment methods.

"We could have new treatments that would not only slow down diseases, but stop or even cure them."

The right material would make sensors part of the body

What happens when you get a splinter in your finger and can't get it out? To protect you, your body grows scar tissue around the stick. This is a good thing, as otherwise an infection might spread and potentially endanger your life. Your body will react the same way when, instead of a splinter, it encounters an object, such as a sensor, intentionally placed there for therapeutic purposes.

The immune system that protects us makes Emilia Peltola's work challenging because the scar tissue, which develops around a sensor, prevents the substances it's supposed to measure from reaching its surface. And this prevents accurate measurements.

Researchers hope that sensors embedded into the body would become part of its tissue. This is what happens when nerve cells attach to sensors. But our body can send glial cells to surround sensors, and they form scar tissue that hampers measurements. In order for a sensor to attract the right kinds of cells, its surface must be of a specific type. But researchers have not yet determined what this type is like.

Good and bad proteins

Solving the scar tissue problem alone will involve plenty of work. In addition, proteins are causing a headache as well.

Proteins are the building blocks of all cells and they perform nearly all of a cell's functions: cell motility, cell fusion, signal transduction and immune defense. But proteins, though vital to humans, are detrimental to the functioning of sensors. They settle on the surface of the sensor, preventing the substance being measured from getting there. The sensors work well in saline solution, but whenever the fluid, such as a blood sample or cell culture, contains proteins, measurements are not as successful.

Research is made more challenging by the finding that protein attachment on the surface doesn't always ruin measurements. The correlation between the functioning of a sensor and the amount of proteins remains a mystery, however. Experiments have detected that a sensor's electrochemistry still functions even when lots of proteins are attached to its surface. This means that the presence of proteins in large amounts alone doesn't mean that a sensor won't function. Researchers still need to explore how surface structures could be used to steer the attachment of proteins in a way that doesn't disturb measurements.

Nanofibre thickness is decisive

Emilia Peltola works at Micronova, which has good facilities for experimental research. Sterile working is a must for examining finished sensors, although an actual cleanroom is not required. A cabinet in her lab holds various sample sensors for study. Their materials combine different carbon allotropes. Once sensor materials are prepared, it is time for the actual experiments, which study the measuring of neurotransmitters as well as interactions between cells and various carbon surfaces or between proteins and surfaces.

While researching carbon nanofibers, Peltola and her colleagues have identified a connection between the thickness of nanofibers and cellular shapes. This link has helped them deduce that thickness also affects which cells, desirable nerve cells or undesirable glial cells, attach onto sensor surfaces.

Peltola thinks her research might progress to animal testing over the course of the five-year Academy of Finland study. Even if it takes more than a decade for the final product to make it into use, the study will provide useful and applicable knowledge for nerve and medical research along the way as well as further our general understanding of the brain and various diseases.

The researchers grow carbon nanotubes and fibers on the surfaces of sample pieces or pipette nanodiamonds onto them. Nanofibres and -tubes are made of graphene, a carbon allotrope, and nanodiamonds are microscopically small synthetic diamonds.

Local information of cell cultures can be obtained using this kind of dishes. The bottom of the well contains 44 microscopic sensors laid side by side.