Abstract

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting to produce solar fuel (hydrogen) has long been considered as the Holy Grail to a carbon-free hydrogen economy. The PEC concept to produce solar fuel is to emulate the natural photosynthesis using man made materials. The bottle-neck in realising the concept practically has been the difficulty in identifying stable low-cost semiconductors that meet the thermodynamic and kinetic criteria for photoelectrolysis. We have fabricated a novel p-type LaFeO3 photoelectrode using an inexpensive and scalable spray pyrolysis method. Our nanostructured LaFeO3 photoelectrode results in spontaneous hydrogen evolution from water without any external bias applied. Moreover, the photoelectrode has a faradaic efficiency of 30% and showed excellent stability over 21 hours. From optical and impedance data, the constructed band diagram showed that LaFeO3 can straddle the water redox potential with the conduction band at −1.11 V above the reduction potential of hydrogen. We have fabricated a low cost LaFeO3 photoelectrode that can spontaneously produce hydrogen from water using sunlight, making it a strong future candidate for renewable hydrogen generation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current global energy consumption is approximately 14–15 TW and is expected to double by 2050. At the present time about 85% of energy provided comes from the burning of fossil fuels1,2. The sun is by far the largest renewable source which provides the earth with 100,000 TW of energy annually. Therefore, the energy provided from one hour of sun light illumination is equivalent to mankind’s total energy consumption for one year1. However due to the sporadic nature of solar energy, efficient storage devices need to be developed and employed in order to make solar energy a feasible energy source. Transportable and storable solar fuels (hydrogen) from renewable resources and efficient energy storage can only provide a sustainable pathway for true transformation to renewable energy to address the global challenge related to energy and environment.

A promising way of storing solar energy is via chemical fuels, in particular hydrogen as it is considered as a future energy carrier3,4,5,6. The greatest challenge is to develop a suitable technology for large scale and cost effective solar fuel production to compete with fossil fuel. One way this could be achieved is by using photoelectrochemical (PEC) water splitting which directly converts water and sunlight to solar fuel (hydrogen). Since the discovery of solar water splitting by Fujishima and Honda7, extensive research interest has been growing in developing efficient and stable PEC water splitting devices for a carbon free method of hydrogen generation8,9,10,11,12,13, however the ideal material has not been discovered.

Cost effective solar fuel generation is hindered by the semiconductor material not meeting certain essential criteria to achieve highly efficient solar to hydrogen conversion. These criteria are as follows: (i) the visible part of the solar spectrum must be absorbed for higher efficiency of hydrogen production and the band edges should ideally straddle the redox potential of water splitting, (ii) the photoexcited carriers must separate and migrate to the surface without recombination, (iii) adsorbed species must be reduced and oxidized by the photogenerated electrons and holes to produce H2 and O23,14. Also for cost effective, environmental and scalability issues, earth abundant non-toxic materials should be the focus of research into new semiconductor materials.

Since Fujishima and Honda, who first demonstrated solar water splitting using TiO2 electrode7, the optimal material remains to be discovered. Many common semiconductor materials have been investigated, including TiO215, ZnO16, WO317, α-Fe2O318,19, BiVO420, metal chalcogenides21, Ta3N522 and oxynitrides TaON23. Most of the stable oxide semiconductors such as SnO2, Ta2O5, TiO2, and ZnO are only photoactive in UV region due to their wide bandgap, which limits their absorption of sunlight. While small bandgap metal oxides such as α-Fe2O3, and ZnFe3O4 can harvest maximum solar spectrum, their conduction band potentials are more positive than water reduction potential, thus, they require an external bias for water splitting. Metal chalcogenides such as CdS and CdSe have ideal band structures for spontaneous water splitting but are highly unstable under water photo-oxidation conditions. Similarly, other ideal candidates such as metal nitrides and oxynitrides also suffer from photocorrosion and photo-oxidation, which limits their applications in water splitting.

A number of different p-type semiconductor materials have been developed for PEC water splitting application, such as; Cu2O8, NiO24, CaFe2O425. These photocathode materials show good photocatalytic activity for water splitting. However, a number of issues with these materials inhibit them from performing effectively as PEC devices. Cu2O has been shown to have one of the highest current densities (10 mA cm−2) of metal oxide semiconductor materials and has attracted wide research interest, however it is highly unstable as after a few minutes the material will visibly degrade under PEC performances26. This high level of instability has led researchers to add protective aluminium-doped zinc oxide (AZO) and TiO2 layers to improve the Cu2O stability but this requires complicated, expensive and non-scalable techniques such as atomic layer deposition or sputtering. NiO is a highly stable material under PEC conditions, however exhibit poor photon harvesting performance due to its large band gap (3.45 eV) which only enables it to access to the UV region. CaFe2O4 has been shown to be a very promising material as it has a narrow band gap of 1.9 eV and band edges that straddle the redox potential of water (−0.6 and +1.3 V). This allows CaFe2O4 access to the visible region of the light spectrum and to be able to split water into its constituents (H2 and O2). However, it requires high fabrication temperatures (1100–1200 °C) which does not make the synthesis process very cost effective.

Recently, tremendous research efforts have been made to develop unassisted PEC system for H2 production and Wang et al. has reviewed recent progress made in unassisted PEC water splitting27. Among cheap visible light active and stable oxides, the bench mark PEC device with tandem structure are (i) the core-shell WO3/BiVO4/CoPi with GaAsP photovoltaic has photocurrent of 6.56 mA cm−2 with H2 evolution rate of 102 μmol/h28 and (ii) without photovoltaic assistance p-LaFeO3 photocathode and n-Fe2O3 photoanode based PEC water splitting devices have demonstrated H2 evolution of 11.5 μlmol/h with longest working life of 120 h9. Among single oxide visible PEC materials, α-Fe2O3 is one of the most investigated material, only Pt-doped α-Fe2O3:Co-Pi photoelectrode is reported to generate unassisted H2 from water29. Along with PEC water splitting, LaFeO3 has been involved in photocatalytic dye degradation30,31 and hydrogen evolution20,21 using powder samples. Another important fact related to LaFeO3 is p-type photocurrent characteristics with the potential to act as photocathode in tandem PEC cell. Stable photocathode under PEC condition is highly desirable to progress in field of solar fuel production. However, progress to improve PEC response of LaFeO3 photocathode is very slothful due to the lack of a sophisticated fabrication technique for high quality nanostructured thin films.

To the best of our knowledge, we report for the first time the nanostructured LaFeO3 photoelectrode for spontaneous hydrogen evolution from water without any external applied bias. The LaFeO3 photoelectrode was fabricated by spray-pyrolysis, a novel, inexpensive and scalable method, to create a stable thin film p-type semiconductor material which displays an ideal band structure with band edges saddled above and below the redox potential of water. The fabricated photoelectrode exhibits excellent PEC performance and is stable under redox water condition for more than 21 hours.

Results and Discussion

Material characterization

LaFeO3 photoelectrode was prepared by spraying precursor solution at 150 °C and then annealed at different temperature from 475 °C to 625 °C with an increment of 25 °C to get single phase crystalline LaFeO3 material. The XRD peak patterns are shown in Figure S4. The photoelectrodes were characterised before and after chronoamperometry (CA), PEC and hydrogen evolution test to evaluate any compositional and texture change. The XRD patterns in Fig. 1a represent crystallinity and phases of LaFeO3 before and after tests. The XRD Peak pattern shows that the films are crystalline with LaFeO3 particles preferentially oriented in (121) direction. All peaks correspond to LaFeO3 are indexed to orthorhombic system (JCPDS 00-037-1493). No new phase is detected and there is no crystal structure change after CA, PEC and hydrogen evolution test indicating high material stability of fabricated photoelectrodes. This provides an insight into the stability of the material suggesting that it has high stability on the timescale of the experiments. The peaks marked with an asterisk distinguish peaks arising from tin oxide of FTO substrate from LaFeO3.

Figure 1b shows the Raman shift pattern of LaFeO3, which is in good agreement with previous Raman shift patterns described elsewhere32,33. The pattern presents the structural phase of the thin film before and after chronoamperometric test. It shows that after the chronoamperometric test there is no structural phase change in the film when compared to its fresh counterpart as the pattern overlaps that of the fresh film showing no obvious change. This data is in good agreement with the XRD pattern, providing further support that the film is highly stable and does not degrade into iron oxide and lanthanum oxide. Modes caused by the La vibrations are present below 200 cm−1, labelled 149 cm−1and assigned B2g. Mode 249 cm−1 is the lanthanum-oxygen octahedral tilt mode where it is assigned Ag. Modes between 400–450 cm−1 are correlated to oxygen octahedral bending vibrations, assigned B3g, and modes above 500 cm−1 are oxygen stretching vibrations33. The peaks at 1128 and 1317 cm−1 can be attributed to the two photon scattering, however in the literature it is hotly debated whether the peak at 637 cm−1 is due to impurity or two photon scattering32. However considering the XRD pattern, it is most likely due to two photon scattering as XRD shows a single phase of LaFeO3. No other peaks corresponding to lanthanum oxide or iron oxide was found which is in good agreement to the XRD pattern.

Figure 2a shows the top view SEM image of the LaFeO3 photoelectrode before the chronoamperometric test. Here it is observed that the nanostructure of the material has excellent compact uniformity and well connected crystal grains in a coral like structure, post-annealing at 550 °C. Figure 2b shows the top view SEM image of the film after the chronoamperometric test. We can clearly note that the film retains its uniformity and good interconnection between the crystal grains. Figure 2c shows the FIB-SEM cross section of the film with thickness of 382 nm. In addition, Figure S1 shows the EDS of LaFeO3 indicating the lanthanum, iron and oxygen peaks. This further confirms the composition of the materials, which aligns with the XRD and Raman patterns. Figure S2 shows that the lanthanum and iron are homogenously mixed in the LaFeO3 film, by element mapping from top view EDS characterization, further emphasizing the uniformity of the film.

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) analysis

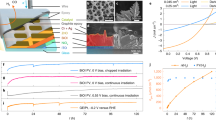

The PEC performance of LaFeO3 was performed in 0.1 M aqueous NaOH (pH 13) solution by illuminating the photoelectrode from the electrolyte side, where the light was chopped every 0.01 V. The photocurrent density (J) is plotted against bias potential (V) as shown in Fig. 3a. The steady state photocurrent onset potential estimated from the J-V plot was at 1.2 V vs. RHE. The photocurrent density rises up to approximately 0.16 mA cm−2 at 0.26 V vs. RHE, while no clear dark current is observed between the measured potential ranges. Due to the compact nature of the film it will be difficult for the electrolyte to penetrate deep into the film, thus we have a relatively low photocurrent. The large spikes during each chop is due to transient electrons generated undergoing recombination with their respective hole, as the accumulated charges do not have enough time to interact with the electrolyte before/after each rapid chop. This recombination effect can be seen when comparing Fig. 3a J-V plot to the J-V plot of Figure S3, where the light was chopped at a slower rate every 0.5 V. As the light is chopped at a slower rate it allows the accumulated charges enough time to interact with the electrolyte solution allowing the charges to separate, hence we do not observe the spikes34. This indicate a slow charge transfer dynamics which need to improve and investigate further to enhance the efficiency of LaFeO3 photoelectrodes.

To determine the best fabrication conditions for LaFeO3 photoelectrode, annealing temperature, spray amount and time has been optimised. The annealing temperature was found to be an important factor which directly affected the photocurrent density of LaFeO3 photoelectrodes. The dependence of photocurrent density on annealing temperature is shown as inset in Fig. 3a while XRD peak patterns are given in Figure S4 and the effect of annealing temperature on J-V curve is given in Figure S5. The photocurrent density increases with the increase of annealing temperature and reaches the optimum level at 550 °C. With further increase of the deposition temperature, the photocurrent of LaFeO3 photoelectrodes decreases significantly. XRD shows that at low temperature regime, the decomposition was not completed and the XRD peak for LaFeO3 was not detected at 475 °C. The LaFeO3 XRD peak starts appearing at 500 °C and becomes more crystalline with the increase in temperature. The low photocurrent at lower (<550 °C) and high (>550 °C) temperature regime can be due to incomplete decomposition and sintering of film respectively which can create defects, dislocations and kink sites in the film. These dislocations and kink sites may act as the recombination centres for the photogenerated electron-hole pairs and consequently showing a poor photocurrent density.

The photocurrent density varied with amount of spray solution/time. The amount of spray solution/time was directly correlated to the photoelectrode thickness (data not shown). As expected the photoelectrodes correspond to short spray times are relatively thin whereas the electrodes associated with long spray times are thick. The photoelectrode deposited using 3 ml spray solution shows lowest photoresponse, which increases with increase in spray time and reached to maximum at 5 ml spray amount and then decrease. The J-V characteristics are shown in Figure S6. The photoelectrode which showed the maximum photocurrent density had a thickness of 382 nm and corresponds to 5 ml spray solution/5 minutes of spray time. For electrodes with higher thickness the photogenerated electrons require to travel more before collecting at the FTO substrate (here the electrodes were illuminated from the electrolyte side) depending on the thickness of photoelectrode. The electron transport within LaFeO3 is significantly slow as evident from high recombination spikes in faster chopped J-V (Fig. 3a). The slow and trap dominant charge transport mechanisms within nanostructured matrix have been already reported in other metal oxide semiconductor systems35.

A chronoamperometric test of the LaFeO3 photoelectrode was conducted to determine its stability. Figure 3b shows the results from the test where it was carried out in an aqueous 0.1 M (pH 13) electrolyte solution at a constant potential of −0.3 V over a period of 21 hours under chopped illumination, where the film was illuminated for 45 minutes and in dark for 15 minutes every hour for 21 hours. A small gas bubble accumulation on the surface of the electrode was also observed during the test. From the graph it is observed that over the 21 hour period the photoelectrode remains photoactive giving a very stable response. However, a very slight gradual decrease in current density is observed which could be due to gas bubble accumulation. As the gas bubbles form it causes a shading effect on the photoelectrode as they tend to stick on the electrode surface, decreasing the effective area, increasing the interfacial electric resistance36, hence we see the slight gradual decrease in current density. The slight decrease in photocurrent start after an hour which is in agreement with H2 evolution. Another reason for the decrease of the photocurrent could be due to the space charge accumulation on the surface of the film37. As the reaction is taking place the build-up of surface charge will create a barrier which will prevent the charges being taken up by the electrolyte, as seen in the slight drop in photocurrent. These effects can have an adverse effect on the hydrogen evolution efficiency as less electrolyte is able to penetrate the film to be available for effective charge separation. This can therefore cause a reduction in hydrogen evolution efficiency over time.

Optical and Electrochemical Measurements

Another factor causing the low photocurrent may be due to the incident photons hitting the film not being sufficiently absorbed. This may be due to the film being very thin. An incident photon to electron conversion efficiency (IPCE) measurement was recorded at 0.26 V vs RHE for the LaFeO3 photoelectrode using an aqueous solution of 0.1 M NaOH. This measurement helps to determine how efficiently the photons were being converted to current, shown in Fig. 4. The IPCE threshold exists at about 520 nm, where the maximum efficiency of 3.2% is obtained at 350 nm. The relatively low IPCE exhibited by the LaFeO3 electrode may be due to the combined factors of weak light absorption, hole-electron recombination rate38 and very thin film. The IPCE increased substantially from 400 nm indicating that absorbed photons of different energies have been successfully converted to photocurrents. However, the IPCE value is higher for short wavelength and decrease rapidly over 400–600 nm region compares to absorption spectrum. The IPCE near bandgap at long wavelengths is lower, which is a common characteristic of iron based photoelectrode29. An analysis of IPCE and absorption data allows us to calculate the absorbed photon to electron conversion efficiency (APCE). The APCE is determined from the IPCE and light harvesting efficiency (LHE) using the following equations39:

where A is the absorbance at certain wavelengths and IPCE is determined experimentally. The APCE spectra overlaps with the IPCE spectra over the entire spectral range. The APCE shows a maximum efficiency of 3.5% which is in good correlation to the IPCE, suggesting that the quality of the film is good however it has very weak light absorption capabilities which may account for the low photocurrent (seen in Fig. 3a) and low faradaic efficiency. In principle, it is possible to increase the thickness of active layer to absorb more photons, thus achieving a higher photocurrent. However, increasing the thickness will increase the internal resistance of the device40.

Optical absorbance measurements were taken for LaFeO3 to help determine the materials band gap. Figure 5 presents the material’s absorbance measurement for the LaFeO3 photoelectrode between the ranges of 350–800 nm. The low absorption and IPCE is attributed to very thin and semi-transparent nature of film (shown as an interest in Fig. 4). By using this data the band gap energy (Eg) of the LaFeO3 film can be determined using Tauc plot41, by plotting (αhv)1/n vs. hv and the band gap is determined by the x-axis intersect, where α is the absorption coefficient and hv is determined by 1240/wavelength. n is 1/2 for direct allowed transitions or 2 for indirect allowed transition. In our case n value of 1/2 was selected. α is defined by Beer-Lambert’s law and can be determined by the following equation42:

where A is absorbance at wavelength (λ) and d is film thickness. Figure 5 shows that LaFeO3 photoelectrode has a direct band gap of 2.4 eV, shown where the red line intersects the x-axis. This band gap value for LaFeO3 falls in line with other works conducted43. The narrow band gap illustrates that the material is capable of absorbing visible light.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurement (EIS) was conducted in order to determine the semiconductors flatband potential. Impedance data were fitted in ZView to a Randles circuit to extract the capacitance. The Mott-Schottky plot showed p-type characteristics of our LaFeO3 film. Flat band potential was extracted using the Mott-Schottky equation for p-type semiconductors:

where C is capacitance, e is the electronic charge, ε r is the relative permittivity of materials, ε0 is the permittivity of vacuum, N A is the carrier concentration, k is the Boltzman constant, T is the absolute temperature, A is the area of electrode, V is the applied potential and V fb is the flat band potential44. V fb of LaFeO3 was determined through a linear fit in the linear region of the Mott-Schottky plot and were calculated to be 0.328 V vs Ag/AgCl (Fig. 6). The measured flat band can be converted to the RHE scale using the Nernst equation45:

where ERHE is the converted potential vs. RHE, E° Ag/AgCl = 0.197 V at 25 °C and EAg/AgCl is the experimentally measured potential against Ag/AgCl. The flat band was determined to be 1.29 V vs. RHE. The flat band potential is in good agreement with the photocurrent onset potential measured from J-V curve. Using a varied Mott-Schottky equation46 (equation 6) the carrier density can be calculated.

where e is the electronic charge, ε0 is the permittivity of vacuum, ε is the dielectric constant, ND is the carrier density, Vm is the measured potential and Vfb is the flat band potential. 6 × 103 value is used as the dielectric constant47. The carrier (hole) density was calculated to be 15.27 × 1018 cm−3. With the flatband and band gap values determined, we can construct a relative band alignment of the LaFeO3 material to the waters redox potentials, as shown in Fig. 7. The valance band and the conduction band is shown to be straddling the redox potential of water with a narrow band gap. This suggests that the material is able to generate hydrogen using the visible part of the spectrum, as the conduction band is well above the reduction potential of hydrogen. This data shows that the LaFeO3 photoelectrode is able to produce hydrogen from water.

Hydrogen Evolution Measurement

Figure 8 shows the hydrogen production performance of the LaFeO3 photoelectrode in an aqueous 0.1 M NaOH solution under a constant illumination. The water splitting test was conducted in a custom made glass reactor vessel (Figure S7) with an attached fused silica viewport. The LaFeO3 working electrode and Pt counter electrode were connected by a single looped wire, without any external bias being applied. Hydrogen was being produced spontaneously during the water splitting test during the first 6 hour cycle where the photoelectrode generated 0.18 μmol/cm2 of hydrogen after 6 hours, with a faradaic efficiency of 30%. It then underwent a second cycle of water splitting test to determine if the electrode was re-usable and how much the performance varied. After a further 6 hours illumination, the LaFeO3 thin film generated 0.08 μmol/cm2 of hydrogen (Figure S8). This provides additional evidence that the film is re-useable, although the amount of hydrogen produced is almost halved. In addition, it should be noted that the low amount of hydrogen produced and low faradaic efficiency can be attributed to the low photocurrent generated. The low photocurrent correlates with low hydrogen produced as an insufficient amount of electrons are being generated to produce a high amount of hydrogen, as seen in the J-V curve. Also, the electrons which are being generated are not all being converted to hydrogen as we see a low faradaic efficiency. This can be due to the electrolyte not effectively penetrating the film due to its compact morphology and/or gas bubbles forming on the photoelectrode where they tend to stick on the electrode surface, decreasing the effective area, increasing the interfacial electric resistance and thus increasing the losses36. After the second cycle of water splitting test, the amount of hydrogen produced further decreases. Again this can be because of the gas bubbles accumulating onto the film surface preventing causing a shading effect, inhibition of effective charge separation and/or space charge layer accumulated onto the film surface. This in turn hinders charge separation, lowering efficiency.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a stable p-type LaFeO3 photoelectrode with a coral like nanostructure by a novel and inexpensive spray pyrolysis technique with a post annealing step, which yields a photocurrent density of 0.16 mA/cm2 at 0.26 V vs. RHE. Chronoamperometric studies showed that the LaFeO3 film provides a stable p-type response over a 21 hour period. Optical and impedance data showed that the material is able to straddle the redox potential of water, with the valance band at 1.29 V and conduction band at −1.11 V, and a bandgap of 2.4 eV. IPCE studies revealed that the photoelectrode had an APCE of 3.5%. Water splitting test was conducted in a custom made reactor vessel, where the working electrode and Pt counter electrode was connected by a single looped wire, without any external bias being applied. This in turn yielded 0.18 μmol/cm2 hydrogen after six hours during the first cycle with faradaic efficiency of 30%. To the best of our knowledge this is the first time hydrogen has been produced spontaneously during a water splitting test without any external bias being applied using LaFeO3 photoelectrode as a single material. These findings demonstrate that LaFeO3 is a potential candidate to act as a photoelctrode for unassisted PEC water splitting to generate solar fuel (hydrogen) cost effectively. However further work is required to investigate and improve slow charge carrier dynamics and low light absorption challenges of LaFeO3 photoelectrodes.

Method

Fabrication of LaFeO3 (LFO) Substrate by Spray Pyrolysis

Iron (III) nitrate nonahydrate (1 mmol) was dissolved in methanol and 20 ml 30% solution of NH3 in water was added to generate precipitate of iron hydroxide. The precipitate was collected by centrifuge and washed two times with de-ionized water. Iron hydroxide was then dissolved 0.1 ml of Trifluoroacetic acid (99%) in 25 ml methanol and Lanthanum (III) iso-propoxide (1 mmol) was added. Once fully dissolved, the solution was used for spray pyrolysis.

Fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) glass substrates were cleaned ultrasonically (prior to spray pyrolysis) by ethanol, iso-propanol and acetone 15 minutes each, in that order, and then washed with de-ionized water to remove any remaining organic substances and dried with compressed air. Once cleaned the FTO glass substrate was placed in the centre of a hot plate at 150 °C. The spray system comprised of a syringe pump system (New Era Pump System NE-1000), an ultrasonic atomizer nozzle (Sonozap) 1 mm diameter and a vortex attachment. 5 ml of the precursor solution was sprayed on to the FTO at a rate of 1 ml min−1 assisted with compressed air at a rate of 6 L min−1, which is passed through the vortex attachment to generate a large plume of aerosol to get a uniform coverage on the FTO. After the completion of spray, the films were further annealed at 550 °C for 3 hours in air.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Barber, J. Photosynthetic energy conversion: natural and artificial. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 185–196 (2009).

van de Krol, R. & Grätzel, M. Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Production. (Spriger Science & Business Media, 2011).

Abe, R. Recent progress on photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 11, 179–209 (2010).

Tachibana, Y., Vayssieres, L. & Durrant, J. R. Artificial photosynthesis for solar water-splitting. Nat. Photonics 6, 511–518 (2012).

Huang, Q., Ye, Z. & Xiao, X. Recent Progress in Photocathodes for HydrogenEvolution. J. Mater. Chem. A3, 15824–15837 (2015).

Zhao, Y., Hoivik, N. & Wang, K. Recent advance on engineering titanium dioxide nanotubes for photochemical and photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Energy 30, 728–744 (2016).

Fujishima, a. & Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972).

Luo, J. et al. Cu2O Nanowire Photocathodes for Efficient and Durable Solar Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 16, 1848–1857 (2016).

Yu, Q. et al. Highly Durable p-LaFeO3/n-Fe2O3 Photocell for Effective Water Splitting under Visible Light. Chem. Commun. 51 (2015).

Hu, S. et al. High-performance 1D type-II TiO2@ZnO core-shell nanorods arrays photoanodes for photoelectrochemical solar fuel production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 403, 126–132 (2017).

Suzuki, T. M. et al. Photoelectrochemical hydrogen production by water splitting over dual-functionally modified oxide: p-Type N-doped Ta2O5 photocathode active under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 202, 597–604 (2017).

Basu, M. et al. CoSe2 Embedded in C3N4: An Efficient Photocathode for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 26690–26696 (2016).

Septina, W. et al. Photosplitting of water from wide-gap Cu(in,ga)S2 thin films modified with a CdS layer and pt nanoparticles for a high-onset-potential photocathode. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 8576–8583 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Synergetic effect of copper species as cocatalyst on LaFeO3 for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 13918–13925 (2015).

Hoang, S., Berglund, S. P., Hahn, N. T., Bard, A. J. & Mullins, C. B. Enhancing visible light photo-oxidation of water with TiO 2 nanowire arrays via cotreatment with H 2 and NH 3: Synergistic effects between Ti 3+ and N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3659–3662 (2012).

Chen, H. M. et al. Quantum Dot Monolayer-Sensitized ZnO Nanowire-Array Photoelectrodes: True Efficiency for Water Splitting. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 6102–6105, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201001827 (2010).

Wang, G. et al. Hydrogen-treated WO3 nanoflakes show enhanced photostability. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 6180 (2012).

Tahir, A. A., Upul Wijayantha, K. G., Saremi-Yarahmadi, S., Maznar, M. & McKee, V. Nanostructured α-Fe2O3 thin films for photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation. Chem. Mater. 21, 3763–3772 (2009).

Hisatomi, T. et al. Enhancement in the performance of ultrathin hematite photoanode for water splitting by an oxide underlayer. Adv. Mater. 24, 2699–2702 (2012).

Zhong, D. K., Choi, S. & Gamelin, D. R. Near-complete suppression of surface recombination in solar photoelectrolysis by ‘co-Pi’ catalyst-modified W:BiVO4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 18370–18377 (2011).

Sun, J., Liu, C. & Yang, P. Surfactant-free, large-scale, solution-liquid-solid growth of gallium phosphide nanowires and their use for visible-light-driven hydrogen production from water reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19306–19309 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Vertically aligned Ta3N5 nanorod arrays for solar-driven photoelectrochemical water splitting. Adv. Mater. 25, 125–131 (2013).

Higashi, M., Domen, K. & Abe, R. Highly stable water splitting on oxynitride TaON photoanode system under visible light irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6968–6971 (2012).

Nail, B. A. et al. Nickel Oxide Particles Catalyze Photochemical Hydrogen Evolution from Water; Nanoscaling Promotes P - Type Character and Minority Carrier Extraction. ACS Nano 9, 5135–5142 (2015).

Ida, S. et al. Preparation of p-type CaFe2O4 photocathodes for producing hydrogen from water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17343–17345 (2010).

Paracchino, A., Laporte, V., Sivula, K., Grätzel, M. & Thimsen, E. Highly active oxide photocathode for photoelectrochemical water reduction. Nat. Mater. 10, 456–461 (2011).

Peerakiatkhajohn, P., Yun, J.-H., Wang, S. & Wang, L. Review of recent progress in unassisted photoelectrochemical water splitting: from material modification to configuration design. J. Photonics Energy 7, 12006 (2016).

Pihosh, Y. et al. Photocatalytic generation of hydrogen by core-shell WO3/BiVO4 nanorods with ultimate water splitting efficiency. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–10 (2015).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Single-crystalline, wormlike hematite photoanodes for efficient solar water splitting. Sci. Rep. 3, 1–8 (2013).

Li, F. tang et al. Preparation of Ca-doped LaFeO3 nanopowders in a reverse microemulsion and their visible light photocatalytic activity. Mater. Lett. 64, 223–225 (2010).

Li, S. et al. Photoinduced charge property of nanosized perovskite-type LaFeO3 and its relationships with photocatalytic activity under visible irradiation. Mater. Res. Bull. 42, 203–212 (2007).

Popa, M., Frantti, J. & Kakihana, M. Lanthanum ferrite LaFeO3+d nanopowders obtained by the polymerizable complex method. Solid State Ionics 154–155, 437–445 (2002).

Romero, M., Gómez, R. W., Marquina, V., Pérez-Mazariego, J. L. & Escamilla, R. Synthesis by molten salt method of the AFeO3 system (A=La, Gd) and its structural, vibrational and internal hyperfine magnetic field characterization. Phys. B Condens. Matter 443, 90–94 (2014).

Kamimura, J. et al. Photoelectrochemical Properties of GaN Photoanodes with Cobalt Phosphate Catalyst for Solar Water Splitting in Neutral Electrolyte. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 12540–12545 (2017).

Peter, L. M. & Wijayantha, K. G. U. Electron transport and back reaction in dye sensitised nanocrystalline photovoltaic cells. Electrochim. Acta 45, 4543–4551 (2000).

Hernández, S., Barbero, G., Saracco, G. & Alexe-Ionescu, A. L. Considerations on oxygen bubble formation and evolution on BiVO4 porous anodes used in water splitting photoelectrochemical cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 9916–9925 (2015).

Lopes, T. et al. Hematite photoelectrodes for water splitting: evaluation of the role of film thickness by impedance spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 16515 (2014).

Tahir, A. A. & Wijayantha, K. G. U. Photoelectrochemical water splitting at nanostructured ZnFe 2O 4 electrodes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 216, 119–125 (2010).

Kumar, M. H. et al. Decoupling light absorption and charge transport properties in near IR-sensitized Fe2O3 regenerative cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3280 (2013).

Cho, S. et al. Bulk heterojunction solar cells with internal quantum efficiency approaching 100. Nat. Photonics 3, 297–302 (2009).

Viezbicke, B. D., Patel, S., Davis, B. E. & Birnie, D. P. Evaluation of the Tauc method for optical absorption edge determination: ZnO thin films as a model system. Phys. Status Solidi 252, 1700–1710 (2015).

Ghobadi, N. Band gap determination using absorption spectrum fitting procedure. Int. Nano Lett. 3, 2 (2013).

Phokha, S., Pinitsoontorn, S., Maensiri, S. & Rujirawat, S. Structure, optical and magnetic properties of LaFeO3 nanoparticles prepared by polymerized complex method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 71, 333–341 (2014).

Gelderman, K., Lee, L. & Donne, S. W. Flat-Band Potential of a Semiconductor: Using the Mott–Schottky Equation. J. Chem. Educ. 84, 685 (2007).

Gómez-Solís, C., Ballesteros, J. C., Torres-Martínez, L. M. & Juárez-Ramírez, I. RuO2-NaTaO3 heterostructure for its application in photoelectrochemical water splitting under simulated sunlight illumination. Fuel 166, 36–41 (2016).

Azumi, K., Ohtsuka, T. & Sato, N. Mott-Schottky Plot of the Passive Film Formed on Iron in Neutral Borate and Phosphate Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 134, 1352–1357 (1987).

Qiu, Y. et al. Size effect on magnetic and dielectric properties in nanocrystalline LaFeO3. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 25, 760–764 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge EPSRC-DTP for Ph D student ship to GSP. The financial support was provided by Engineering and Physical Science Research Council, UK (EPSRC) under the research grant No EP/P510956/1 and EP/R512801/1. We also acknowledge UKIERI-DST2016-17-0089 project for partly funding the present work. NSG Pilkington Glass Ltd. is acknowledged for kindly providing the FTO substrates for this work. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S.P. and A.A.T. jointly conceived the study, the experiments therein and participated in manuscript preparation. G.S.P. performed all practical experimentation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pawar, G.S., Tahir, A.A. Unbiased Spontaneous Solar Fuel Production using Stable LaFeO3 Photoelectrode. Sci Rep 8, 3501 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21821-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21821-z

This article is cited by

-

Solvent-induced morphological formation, optical and photoelectrochemical performance of α-Fe2O3 photoanode

Bulletin of Materials Science (2022)

-

Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance of Chemically Grown Pristine Hematite Thin Films

Journal of Electronic Materials (2022)

-

Enhancement of Photoelectrochemical Reduction by LaFeO3 Photocathodes Coated with Electroless Deposited Nickel Boride Catalyst

Catalysis Letters (2020)

-

The effects of the oxygen content on the photoelectrochemical properties of LaFeO3 perovskite thin films obtained by pulsed laser deposition

Applied Physics A (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.