In Slate’s annual Movie Club, film critic Dana Stevens emails with fellow critics—this year, Justin Chang, Odie Henderson, and Alison Willmore—about the year in cinema. Read the previous dispatch here.

Dear Moviefilm Clubbers,

Since I already wrote a fair amount about crotch grabbing in my previous post, I will gladly steer us far, far away from Rudy’s giunitalia and Borat Subsequent Moviefilm in general. That’s a movie I wish I’d liked more myself, though kudos to Sacha Baron Cohen for taking what might have seemed a fatal flaw in less daring hands—a lingering sense of comic futility, even defeat—and reverse-engineering it into, well, the whole damn point: This isn’t funny anymore! And maybe it never really was. It’s worth noting that Borat Subsequent Moviefilm emerged just a few weeks after Alex Gibney’s Totally Under Control (co-directed with Ophelia Harutyunyan and Suzanne Hillinger), a deadly serious COVID-19 primer/exposé that felt like the perfect companion piece to Baron Cohen’s gonzo shenanigans. What an inspiring double bill: two movies—one mock, one doc—shot on the fly during a pandemic and released right before the most consequential election of our lifetimes, both hellbent on bringing an end to the Not-So-Glorious Nation of Trumpistan.

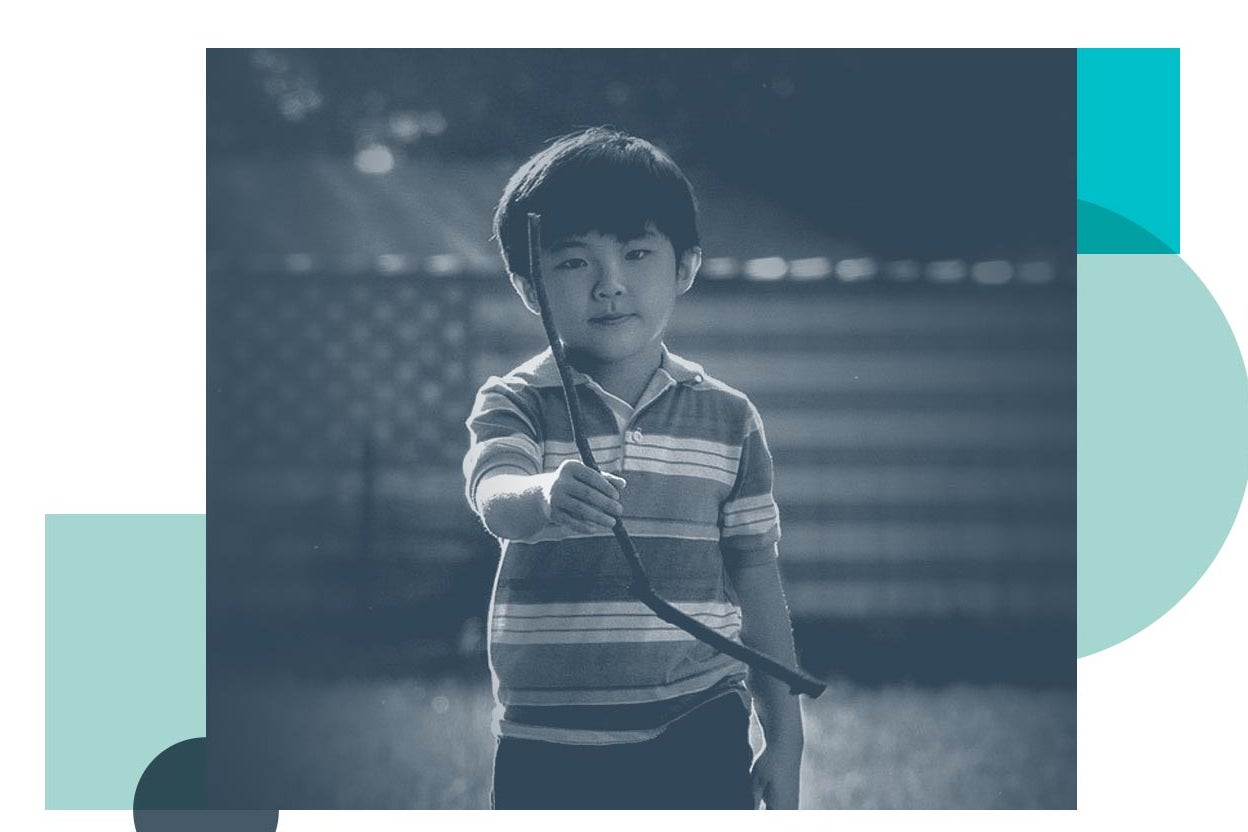

But enough! Dana requested a departure, and I think I have an answer. One of my strangest, most rewarding and surely unprecedented experiences of 2020 was getting to watch as a close friend’s deeply personal movie took a major film festival by storm, generating heaps of critical praise, audience love and, yes, that fickle but oh-so-seductive mistress, awards-season buzz. I’m talking about my buddy Isaac, aka Minari writer-director Lee Isaac Chung, whose (wonderful!) movie I’ve been pretty silent about all year, beyond one congratulatory tweet and a full disclosure–y mention in my Sundance coverage. Professional ethics obviously barred me from reviewing the film, and I’m not about to do so now, not even in an off-the-cuff, let-it-all-hang-out personal forum like the Slate Movie Club. Especially since I’ve got a micro-credit on the movie: Yes, in a story that lovingly re-creates the details of his 1980s Arkansas childhood, Isaac somehow found room to give his chronic-punster critic friend a printed cameo. (Watch that early dowsing scene closely and you’ll spot a throwaway dad joke that I’m stupidly, inordinately proud of.)

Needless to say, my response to Minari is both biased and informed by my affection for Isaac and my knowledge of him as a person—and by that, I don’t mean his upbringing as the son of Korean immigrants, the details of which were as delightful and moving a surprise for me as they were for many other moviegoers. I’m speaking more of his artistic sensibility, the ways I’ve seen this fellow Terrence Malick–loving, Hou Hsiao-hsien–worshipping cine-nerd evolve over a roughly 15-year filmmaking career. Minari fans will get a sense of just how expansive that sensibility is if they check out his 2007 feature Munyurangabo, a quietly galvanic portrait of life in post-genocide Rwanda that I have zero conflict-of-interest qualms about recommending. Notably, Munyurangabo does pretty much the opposite of what the semi-autobiographical Minari does: It’s a bracing reminder that, with the right balance of sensitivity and artistry, a person can make indelible, clear-eyed cinema about a community that isn’t, strictly speaking, their own.

Over the past few months, a few folks have reminded me that my necessary (if now briefly broken) vow of Minari silence has meant that there’s one Asian American critic fewer weighing in—positively, negatively, or in between—on a significant movie from an Asian American filmmaker. Part of me loathed writing that sentence; part of me sees their point. Are there points of overlap between my experience and Isaac’s? Sure there are: immigrant parents who worked like hell to provide for us; an early exposure to evangelical Christianity; a fractured sense of identity—of feeling neither fully Asian nor fully American—that a love of the movies, among other things, helped us heal and make sense of.

But of course, there are as many differences as there are similarities. I’m Chinese American, not Korean American, for starters, and grew up in suburban Orange County, not rural Arkansas. It would be reductive to assume that my very different experience gave me some particularly probing insight into Isaac’s. But then, a lot of us are used to being lumped under the “Asian American” umbrella, and sometimes even lumping ourselves together as a matter of habit. I can’t help but be reminded of this keen insight from Karen Han’s own Slate review: “Even now, the most frequent points of comparison for Minari have been the works of the Japanese directors Hirokazu Kore-eda and Yasujirō Ozu, as if there were no Korean or Korean American directors who have also made powerful art out of simple family stories (and as if all films made by filmmakers of Asian descent should be compared with the work of other Asians).” A-fucking-men to that.

The priorities at work here are complicated and sometimes contradictory: How do we ensure that critics of color are given the chance to write about work they may have some particular affinity for or knowledge of, but without leaving those critics feeling typecast or pigeonholed? How do we encourage and foster greater inclusivity in the arts and arts journalism without falling into a rigidly proscriptive approach? For now, I’d settle for a Hollywood Foreign Press Association that doesn’t think it makes sense to shunt one of the year’s most thoroughly American movies into a category called “best foreign-language film.”

I’ll end where Dana began, with Nomadland, which is fitting for a picture whose yearlong road trip comes full circle with one of 2020’s most achingly beautiful movie endings. My own travels with Nomadland have been similarly cyclical: I admired Chloé Zhao’s picture enormously when I first watched it on a screener months ago, and I liked it even more when I attended a drive-in screening at the Rose Bowl (hosted by this year’s sadly canceled Telluride Film Festival), which was in some ways the ideal venue: What better place than a giant parking lot to see a movie largely set in giant parking lots?

But I didn’t fully fall in love with it until my third viewing, again on a screener, shortly before sitting down to write my review. Fully knowing what to expect, yet still utterly engrossed in every twist and turn of the journey, I simply collapsed into Nomadland in a way I’ve rarely collapsed into any movie. One moment Frances McDormand was driving along a winding desert road; the next moment I was doubled over on my couch, ugly-sobbing so loudly that my wife and 4-year-old came running to see what on earth was the matter. I couldn’t explain it to them, really, any more than I can explain it now: Was it a Pavlovian response to that gorgeous Ludovico Einaudi score? Was it a simple rush of love for Fern, or Frances (I barely care to tell the difference), who so fully commands our sympathy in part because she so utterly refuses our pity? Was it a feeling of joy that, even within the diminishing parameters of a TV screen, a movie could still sweep me away? Was it a weird, belated burst of relief over the outcome of the election, something that’s been hitting me every few hours and days since mid-November? (And yes, I know Nomadland isn’t explicitly about that, though if we’re honest, it isn’t not about that, either.)

On an understated, almost molecular level, I think Nomadland is simply attuned to the realities of human loss—emotional, material, societal, spiritual—in ways that very few movies are, and that means something in a year marked by levels of loss we haven’t even begun to wrap our minds around. But if Zhao’s film is a heartbreaker, it’s not a downer: It’s a portrait of individual and collective American tragedies that nonetheless finds scraps of joy, hope, and community in the margins, and weaves them into something lyrical and restorative. And it does all this with an effortlessness, a playfulness even, that I think explains why—for all the praise that’s been heaped upon it—the movie still feels curiously and even grievously underloved. I can’t wait for audiences to discover it in 2021. I also can’t wait to see you guys, inside or outside a theater, at a festival or on Twitter, safe and sound and still happily in thrall to this art form we love.

Justin