n a state well-known for the shimmering lights of the Las Vegas Strip, Nevada is getting some international recognition for something decidedly darker.

It’s the state’s night skies. In fact, rural Nevada has some of the blackest nighttime skies on the planet.

This year the isolated Massacre Rim Wilderness Study Area, in the state’s far northwest reaches, was named an International Dark Sky Sanctuary, becoming only the 10th place on Earth to receive such a designation.

Out there, the night skies are so dark, astronomers say, you can see your shadow by the light of the Milky Way.

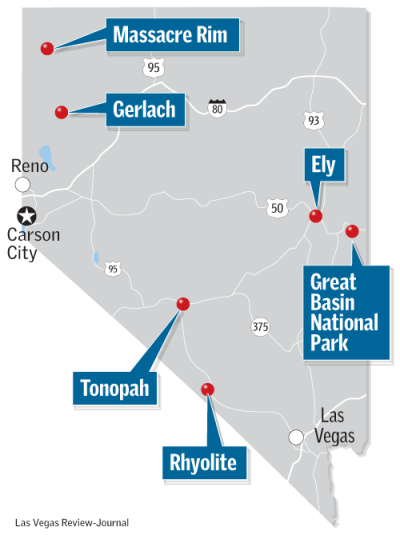

But amateur stargazers say Southern Nevadans don’t have to travel that far to appreciate the nighttime. The heavens shine nearly as brightly from tiny Ely and Gerlach to Great Basin National Park and even Tonopah.

The nonprofit group Friends of Nevada Wilderness wants to help many forsaken high-desert communities use those dark skies to attract tourism by developing promotional brochures and advertising campaigns.

Since it started its summertime Star Train five years ago, Ely has drawn tourists from as far away from Australia and China. At $41 per adult, the rides, which run 60 miles to Great Basin, also bring business to local hotels and restaurants.

Kyle Horvath, director of tourism for White Pine County, estimates the Nevada Northern Railway’s specialty theme rides are bringing in $3 million annually, and he expects that figure to rise “significantly” in the next few years.

The success of the stargazing rides has convinced the county to invest in other after-dark activities. They include nighttime photography seminars, sponsored hikes and family events at local night viewing parks.

“New construction is required to use lighting that does not pollute our night skies, which bring a unique niche to our area,” he said.

Something to be proud of

Look at any map that plots the United States at night and you’ll see that most of the nation is dominated by light — about 80 percent of Americans can no longer see the Milky Way.

The West is different, a place where the night is filled with delicious darkness.

In 2017, travel writer Oliver Roeder designated Gerlach in the Black Rock Desert as “The darkest town in America” in his search for the nation’s least-lighted places.

“On NASA maps, you can see the lights from Las Vegas, Reno and Salt Lake City. Then there’s central Nevada,” said Nichole Andler, chief of interpretation for Great Basin. “It’s like a big hole in the middle of things, just really dark. It’s wonderful and something Nevadans should be really proud of.”

The reason? The lack of a human footprint.

Most of rural Nevada is undeveloped, with ranchers and farmers clustered around water, a commodity in short supply. The Silver State is also dominated by mountains and an array of higher, clearer altitudes — almost Martian in its unpeopled loneliness.

Melodi Rodrique a physicist at the University of Nevada, Reno, uses remote access to the Great Basin Observatory in her astronomy class. She relishes her occasional drives to the national park and its high-altitude observatory.

“There’s really nothing out there,” she said. “You drive and you drive and you drive and you don’t see anybody or anything. There’s nothing but beautiful desert.”

It’s not just scientists who are drawn Nevada’s rural darkness.

Great Basin National Park attracts 10,000 night-sky visitors each year, many of them attending its annual astronomy festival.

Yet some believe the state can take even better advantage of its natural wonders.

“There are people worldwide who care about dark skies,” said Shaaron Netherton, executive director of Friends of Nevada Wilderness. “And we’ve got them right here. They could provide an economic boost to a lot of small towns.”

Netherton is producing brochures with new night sky tourism slogans, such as designating Nevada’s isolated stretch of U.S. Highway 6 as “The starriest road in America,” a play on the old U.S. Highway 50 campaign that boasted about the road’s loneliness. Then there’s a tour she said could be called “Park to Park in the Dark.”

Several months ago, the International Dark Sky Association selected Nevada’s Massacre Rim as an elite night sky sanctuary, following a joint application by Netherton’s group and the Bureau of Land Management. The site joined similar sanctuaries in New Mexico, Texas, Utah, New Zealand and Chile.

But the area, located 150 miles north of Reno near the Oregon and California borders, is so isolated, with so few roads, that most stargazers must hike in to find their viewing spots.

Across the rural outback, Nevadans get a kick out of introducing their city cousins to real darkness.

“I like to take people out to the Black Rock Desert, set up chairs for the sunset and then lay down on blankets and just watch the stars,” Netherton said. “Out there, you have a 360-degree view of the heavens.”

Andler, Great Basin National Park’s chief of interpretation, said the number of tourists who visit the park just to see the stars increases every year. On those trips, she’s often asked, “What’s that fuzzy thing in the sky? They’ve never seen the Milky Way before. They’re spellbound by the dark bands and dust clouds and the fact that there’s so many stars.”

Some rural Nevada old-timers have been enjoying the view for decades.

James Heidman helped organize the Tonopah Astronomical Society, which once boasted 15 members until people moved away. Now 73, he’s lived in Tonopah for 26 years and likes to search for what he calls “deep sky objects.”

“One night, it was so dark out there, the air was as still and crystal clear as can be,” he recalled. “Jupiter has 50 or 60 moons, but only four of them are good-sized. On most nights, you can see them as mere points of light. But that night, we could see them as actual discs. It was pure wonder.”

‘Then the clouds parted’

Some night sky watchers have even explored deep space from within the big-city limits.

In 1997, Las Vegas lawyer and amateur astronomer John Mowbray photographed the Hale-Bopp comet as it hurtled over Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area at a brisk 43,000 miles an hour.

Mowbray’s story of capturing the elusive comet shows how mystical such nighttime encounters can be.

He said his father had just recently died, and he felt a bit philosophical as he ventured out to Red Rock Canyon at dusk to set up his tripod and camera. The evening was cloudy and windy, and he eventually decided to call it a night.

“Then the clouds parted and I went crazy,” he recalled. “I shot five rolls of film and drove to the local Walmart, where a nice lady and I worked together to develop the images.”

Mowbray will always remember that night and others like it — being out there, alone, just him and the stars. “You stare up at the Orion Nebula, where stars are formed, knowing that the light hitting your retinas was generated 650 years ago,” he said.

“And you have to ask, ‘Does it even exist anymore as I’m seeing it now?’ It’s like a time capsule. And it puts a whole lot of things in your life into perspective.”

‘It’s showtime!’

Russ Gartz is a guide at the Tonopah Star Trails and Star Park, which hosts summertime events known as Star Parties. He sees the money and wonder stars bring into town.

Once, a French couple asked him to hold their baby daughter as they looked through his telescope. On another night, a British tourist found the Andromeda galaxy without using a star map.

On a recent late fall evening, far from Las Vegas, where chronic light pollution eclipses the night skies,the sun has just set, casting the western horizon of Tonopah in a rich, glowing crimson. That’s when Gartz strides out of a convenience store, ready for another dark sky mission.

The 58-year-old retired government worker is prepared — red cap, two pairs of socks (two of everything, actually), ready for temperatures to dip into the high 20s.

Gartz likes to arrive early so he can position his telescopes and binoculars just so, welcoming each new point of light as it appears in the sky. He’s like a dutiful social host, extending a hand to greet each arriving celestial guest at his regular evening star party.

He starts up his old truck, hurrying to take an observational post just outside town. From there, he gazes up into the distant realm he calls “the heavens,” suggesting that Gartz regards any communion with these night skies as a near-religious experience.

Gartz is on the lookout for such otherworldly celebrities as the Orion and Cassiopeia constellations or the seven sisters of the Pleiades, a nearby star cluster that appears even to the unaided eye.

But he says he also likes the moon for its mysterious cultural references, reciting the poetry of Maleva the Gypsy from the 1941 film “The Wolf Man.”

“Even a man who is pure of heart and says his prayers by night,

May become a wolf when the wolf bane blooms and the autumn moon is bright!”

At a viewing spot on the old Mizpah Mine site, overlooking downtown Tonopah, Gartz adjusts his telescopes, casting around in his orange tackle box for lenses and screws.

At long last, as a nearby dog barks, he’s ready.

“It’s showtime!” Gartz said. “Let’s look into the skies!”

He points out Cassiopeia, which he likens to “a bent question mark.” Along with the setting moon, he directs his telescopes toward Jupiter, where its four visible moons can be seen lining up like planes preparing to land at McCarran International Airport. Saturn — even its glorious rings — is also clearly visible.

By 8 p.m., it’s so dark, even this close to town, that Gartz negotiates by flashlight. He points out the Milky Way and later a shooting star.

As the night wears on, he continues his search for those seven sisters. But his quarry seems lost amid the endless pinpricks of glimmering light. Ursa Major, also known as the Big Dipper, sits on the northern horizon like a huge, starry ladle.

“Where are my Pleiades?” he says. “I just saw you two nights ago.”

Finally, success.

“The Pleiades!” he cries out. “Ah! There you are!”

To answer questions from curious tourists, Gartz carries his trusty amateur astronomy guide. He also has an iPad with a “Star Walk” application that breaks down the complex map of stars into mythological figures as the ancients might have imagined them.

“Each night, the heavens expose just how little I know about them,” he said. “But the views are endless and there’s always time to learn.”

After a few hours, Gartz packed up his telescopes. He could stay out here all night, a rural star gazer content to be out under Nevada’s dark skies.

But he has to work in the morning.

“Nature,” he said softly, “is the ultimate cool.”

John M. Glionna is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer. He may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com.

International Dark Sky Sanctuaries

— !Ae!Hai Kalahari Heritage Park (South Africa)

—Aotea / Great Barrier Island (New Zealand)

—Cosmic Campground (New Mexico)

—Devils River State Natural Area - Del Norte Unit (Texas)

—Gabriela Mistral (Chile)

—Massacre Rim (Nevada)

—Pitcairn Islands (British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean)

—Rainbow Bridge National Monument (Utah)

—Stewart Island / Rakiura (New Zealand)

—The Jump-Up (Australia)