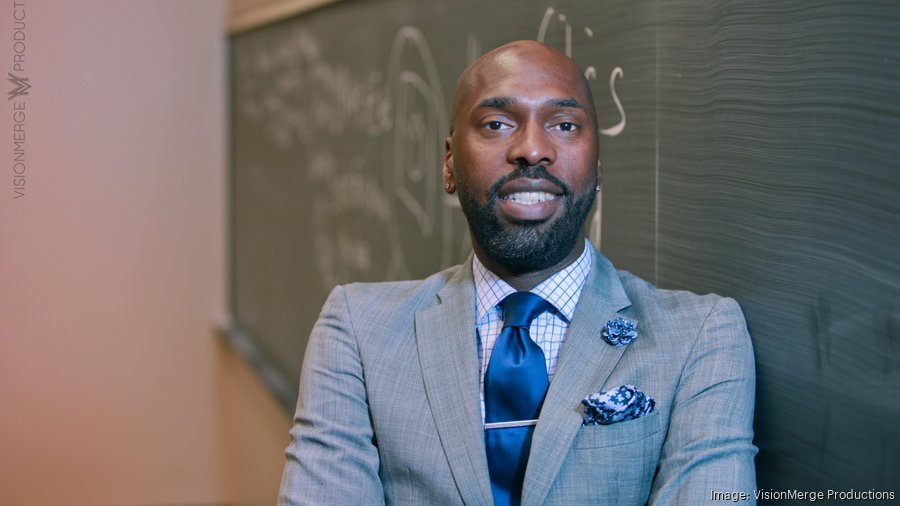

Davarian Baldwin believes it's time to recognize — and respond to — the ways in which wealthy, elite universities have grown and operated in respective to the cities where they reside.

His research and writings as a professor at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, documents how colleges and universities, many with billion-dollar endowments, have amassed billions more in land, property and assets over the past several decades, even as signs of decay have spread in some of the communities that surround them. In short, his findings describe a higher ed model geared to generate profits and wealth, albeit one veiled behind the core mission of an institution of advanced learning.

In his upcoming book, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower (due to publish March 30), Baldwin takes some of America's most prestigious colleges — including his own employer — to task for deals that have displaced and disadvantaged vulnerable communities in some of the country's biggest cities. He also argues it's high time to revisit many of the policies that have enabled schools to follow this course for so many years, including the possibility that portions of their operations should be taxed like any other for-profit institution.

Baldwin recently spoke with The Business Journals’ Hilary Burns about, among other things, the need for more public oversight of colleges and universities and how a school in Canada could serve as a model for the higher ed sector in the U.S. The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Interested in reading more higher education news from The Business Journals? Sign up here for our twice-weekly newsletter covering the latest developments and featuring exclusive interviews with education leaders in this fast-changing sector.

In your book, you propose more public oversight of colleges and universities in urban areas. What could that oversight look like?

In talking with various people in my travels on this book, one theme that kept coming up was the idea of a community planning oversight board. Therefore, any expansion plans that were put forth by a university or college or medical school or affiliated organization would have to go through some type of oversight to talk about and discuss its impacts on the surrounding community.

Right now, Northwestern University is putting together a public safety board around policing. The University of Winnipeg has a community advisory board when it comes to putting together an agreement to share space in their new recreational facility with community groups. There is an organization in Chicago which is proposing a community advisory board for any type of university expansions on the south side of Chicago.

There's been some debate in terms of ... is it advisory? Does it have legislative power? That's something that would have to be debated and discussed. I would advocate for stronger oversight. But I know that right now the trend is more towards just an advisory capacity.

Your book digs into Yale University and its hometown of New Haven. how much would the city of New Haven benefit from tax revenue produced from Yale?

Substantially. It's funny because there are some in New Haven who I spoke to who (believe) the way New Haven looks is because of city mismanagement. That might be part of the problem. There was an agreement with the state of Connecticut to compensate cities like New Haven for the overrepresentation of nonprofits in their cities to compensate for the loss of property taxes. That budget has never lived up to the promise. The point being the state fully acknowledges that when these nonprofits are overrepresented, it is going to have a profoundly adverse effect on the cities.

They know that and they can try to institute this compensation policy, but the state budget is struggling, so they can't even fully pay out what they promised. That there was profound to me.

On top of that, they're receiving public services like fire, police, trash removal, snow removal, service on the electrical grid. An additional layer to the conversation is that private industry, particularly in biotech and software production, et cetera, are recognizing the power of the property tax exemption to provide a shelter for these industries, particularly in the realm of research and development. Early startups understand the benefits of partnering with a university and having the research and development for their work being done on a university building or on a university campus because it eliminates overhead.

There are multiple layers in which the property tax exemption has an adverse effect on cities. In the case of Yale, they found that they were having a hard time recruiting businesses to come to the city in those industries if they weren't affiliated with Yale because they were being put at a disadvantage. They were having to compete with other industries who didn't have the same overhead costs because they were housed in places that did require property taxes.

Can you talk more about schools and PILOT (Payments in Lieu of Taxes) programs?

The PILOT itself is tricky because it's voluntary. At any point, a university can stop. It's a good activity but the downside of a PILOT is that schools believe that, OK, we've given the PILOT, we're done. It doesn't really account for the actual economic relationship between universities and cities.

The PILOT doesn't account for the ongoing ways in which universities profit from their relationships with cities, and their extraction of wealth from cities. (Some schools), for example, don't even want to offer a PILOT. They would rather offer a donation or a gift ...one that can be written off. And from a legal perspective, giving money in the form of a gift doesn't concede any responsibility or any long-term economic accountability. At least a PILOT acknowledges that there's a relationship.

In my work, I'm calling for a more robust, reconstructed understanding of the way in which the very wealth of a university is built on extracting public resources from the cities. Don't get me wrong: PILOTs are a good start. The gift giving is a good start. But I think that there should be just a reconsideration of what actually goes on in the relationship between universities and their cities.

Whenever I've asked college presidents about the possibility of being taxed, they bristle. How far are we realistically from seeing that happening?

We're far away from that because you have to change to the tax code. That would be state by state. There might be some need for federal oversight. A few years ago, Republican legislators were being critical of universities and higher education. They had a discussion about taxes and endowments, but for them, it was an attempt to attack the so-called liberal elite.

I worry about that, because I don't think that this should be fodder for a political game. I think we need to push that to the side and have a real conversation about the relationship between the universities, their fiscal standing and the degree to which it depends on extracting both public and private wealth from the cities in which they sit. I definitely think it has to be a groundswell of a national campaign because it would require rewriting the state tax codes.

In the case of Yale, their tax exemption was written into law before Connecticut was even a state because Yale is older than the state of Connecticut. So this would require some significant legislative heavy lifting for it to happen.

When you look across the board at higher ed, where do you see progress?

We're seeing the most conversation around policing. ... How does policing serve on the front lines of preparing the city to receive these knowledge (industry) workers and the communities that will keep them? That's where I would like the conversation to go, and I think we're slowly seeing that happen.

There's also been some interesting conversations around health care and university medical centers, because for university medical centers to receive tax exemption, they have to offer indigent care. Recently we've seen again more activists and nurses putting out reports, talking about the ways in which medical facilities are seizing on poor and working class communities, primarily of color, in the neighborhoods surrounding them. They are putting liens on homes and spending more money on lawyers to pursue medical bills than the actual cost of the medical bills.

There's been some pushback around that. If you're going to receive tax abatements or exemptions, you actually need to provide the indigent care that you are responsible for. These universities are not being forthcoming about the kind of bills and services that would be free or heavily subsidized if people were made aware. They're doing this work primarily in communities that are already vulnerable.

Your book also has positive things to say about the University of Winnipeg in Canada and its relationship with the local community. Could that model be replicated in the U.S.?

So much of it. So, Lloyd Axworthy, (former president of University of Winnipeg) came back to the university in the early 2000s and he was also an environmentalist. He put together this vision of sustainability that was not just about LEED-certified building and recycling. He had a four-tier approach that was environmental, social, political and economic.

His initiatives were not all just benevolent. Some of them were self-serving. There was a huge shift in the demographics of those who were going to the university at one point in time, to the typical suburban kids. But then it became indigenous and what they call new Canadians, so immigrant communities were the biggest growing population of college-aged kids. It was a huge explosion in (enrollment) numbers, from about 6,000 to 10,000.

It was a different demographic, so they had to create housing. They saw that engaging with an outside developer was going to be extremely costly, so they created their own development corporation internally. As a part of that, every building was LEED-certified and in addition to that, they included mixed housing. ... You could be a student anywhere in the city and you could be eligible for this housing.

This was a whole different reconstruction of what it meant to be a university in the city. On top of that, they created their own food service organization called Diversity Foods. This is pretty amazing ... they receive 65% of their raw materials from within a 100 kilometer radius and 65% of their employees are from the community. They take the cooking oil that is produced from their work and they send it to be converted to biodiesel. They're trying to turn the labor relations of their facility into collective bargaining so that everybody would have a cooperative. They also take recipes from the community and they build them up to industrial-sized portions.

Don't get me wrong: Winnipeg is not perfect. Some of the buildings that are created come after their own history of displacing residents, so that's something that must be recognized. But they're trying to atone for that.

The same thing could happen in the U.S. There are groups of students right now from the University of Virginia and other places who don't understand why universities have contracts with (food service giants) because the cost of say, chicken nuggets and French fries, is so much more than you would pay. If you're a city university and you want to encourage your students to get out and mix around and support local businesses, it's very difficult to do that because many of these contracts require students, if they live in the dorms, to have a minimum contract with that company at a high premium. It doesn't encourage university students to mix and integrate into the neighborhood. It creates a captive market for food services, for retail or paraphernalia. That has to be changed.

What do you hope a university administrator might take away from your book?

That this is not just some pie in the sky or utopian idea. This could be a new way to invest in new markets, invest in new people by investing in the communities that surround these universities. It could actually become a new fiscal model for sustainability. I think that's very possible.

Instead of just simply chasing the families that will pay $70,000 a year ... invest in the communities that surround these campuses that are filled with Pell-eligible students, workers and health care patients. More humane and just relationships will create a different ecosystem for these universities that could stave off their demise.

This story was published in partnership with the Walton Family Foundation as part of a project in which The Business Journals will report news and analyze national trends shaping higher education in America.