Once the cradle of basic industry, the Alle-Kiski Valley diversifies as it looks forward

Kalmar Chevrolet in Gilpin has weathered many changes since Rudy Kalmar, the son of Czechoslovakian immigrants, founded his family’s car dealership selling Hudsons in 1937.

It’s been handed down through generations of the family, rolled with changes in the auto industry, and persisted through the changing fates and fortunes of the Alle-Kiski Valley and its people.

Where there were once seven new car dealers in the Leechburg area alone, Kalmar is now the only one, and among only a few remaining in Armstrong County, said Len Kalmar, one of Rudy Kalmar’s sons.

“There are still a lot of people here that want personal service. They want someone to take care of them,” Kalmar said. “I wouldn’t want to buy a car and have to drive to Greensburg to get it serviced, or Monroeville.”

Kalmar is among the ranks of businesses that have survived as others have come, gone and changed in the Alle-Kiski Valley.

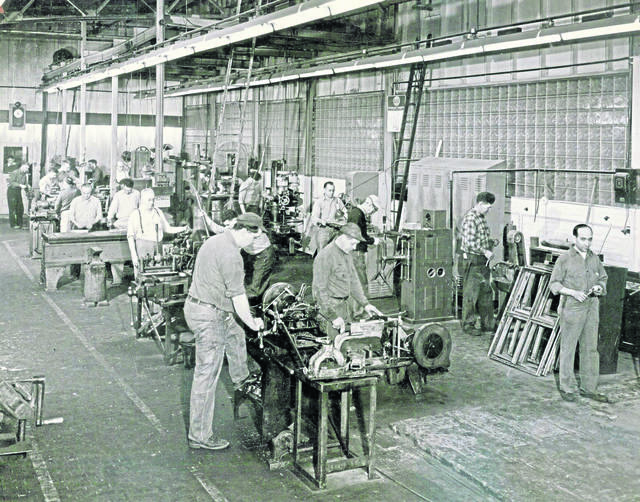

The region, made up of the corners of Allegheny, Armstrong, Butler and Westmoreland counties, is defined by its rivers. The cheap transportation they provided, along with rail, helped build the area’s foundation on steel, glass and aluminum by titans like Allegheny Ludlum Steel (today’s Allegheny Technologies, Inc.), Pittsburgh Plate Glass (today’s PPG Industries) and the Aluminum Co. of America (Alcoa, Arconic).

“This growth, in turn, caused an influx of workers and the subsequent growth of the Valley,” the late historian S. Hartley Johnston wrote.

The industrial collapse of the 1980s hit the area hard, causing many to flee depressed towns, leaving idled plants and empty storefronts behind.

Decades later, many now see the region advancing, with a diverse array of businesses and industries, and a changing function for the rivers from industrial thoroughfare to an amenity that people want to live along.

“It’s definitely on the upswing, I think,” said Lynda Pozzuto, executive director of the Alle Kiski Strong Chamber of Commerce.

Covering parts of the four-county area, including all of Armstrong County, the chamber has about 500 members, including individuals, businesses and industries, and nonprofits.

“We have such quaint towns and communities within our footprint, these older communities,” Pozzuto said. “It’s interesting the different types of businesses that are coming in and filling up the towns now. They’re different and unique businesses.

“There’s something going on in each of these communities,” she said. “It can never be what it was. That’s gone and over.

“It can be something new, something different that can be just as good if not better.”

The A-K Valley’s industrial origins

Salt mining was the region’s first industry. Penn Salt, founded in 1850, was the first large company in the Valley, Johnston said.

The lock-and-dam system built in the 1920s and 1930s made river transportation reliable.

Penn Salt went on to manufacture a variety of chemicals. Its environmental legacy is the Lindane Dump Superfund Site off Springhill Road in Harrison, which remains under monitoring and treatment.

Other parts of the region’s industrial heritage remain operating, although in different capacities. Allegheny Technologies employs more than 1,800 in Western Pennsylvania. Its Brackenridge Operation in Harrison is home to its Hot-Rolling Processing Facility, one of the most efficient and powerful mills in the world.

When ATI completed the more than $1.1 billion facility in 2015, ATI spokeswoman Natalie Gillespie said the company believed at the time it was the largest private investment of its kind in Pennsylvania. The Shell cracker plant in Beaver County has now surpassed that record, she said.

“We’re still very much a viable piece of this community,” she said.

While its first glass factory in East Deer is shuttered, PPG still employs about 450 people at its research and development location shared with Vitro glass in Harmar, and its plant, labs and offices in Springdale, spokeswoman Greta Edgar said.

Alcoa employed thousands at its New Kensington works along the Allegheny in that city and Arnold from 1891 to 1971. Later becoming the Schreiber Industrial Park, the New Kensington Redevelopment Authority bought the property in 2018 with the goal of turning it into a center for advanced manufacturing.

Rivers once key to industry, now recreation

The story of ATI, PPG and Alcoa “is the story of those industries in the Pittsburgh region, and the changing competitiveness of the region as a whole as an industrial center,” said Chris Briem, a regional economist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Social and Urban Research.

“The rivers really were the reason industry was there,” he said.

Industries stretched out from Pittsburgh along the river valleys, Briem said. Then, in the 1980s, no parts of the region escaped the industrial decline.

Since then, Pittsburgh changed to resemble other cities with growth concentrated in the center of the region.

Being on a river is no longer a built-in advantage, Briem said.

“Most industries have much more flexibility in geography these days than they had in the past,” he said.

But that doesn’t mean rivers no longer matter. They can be an amenity, instead.

“They are tremendous assets. They were blocked in Pittsburgh’s industrial heyday,” Briem said. “We’ve now built things to take advantage of the rivers in a different way.”

The Alle-Kiski Valley’s future lies in it being a place where people want to live and being connected to economic opportunities across the broader region, Briem said.

Trying to reindustrialize to the scale of the past is not realistic, he said. Technology fosters smaller businesses with fewer employees; and prosperity can also be found as a “bedroom community.”

“Size is not necessarily a metric of success,” he said. “You can be a smaller place and still be a successful town or prosperous place where people want to live.

“Trying to rebuild to the scale of the past doesn’t make a lot of sense. You want to plan for a size that makes sense.”

Homegrown companies grow

A number of companies employing Alle-Kiski Valley residents were started in the region and remain to this day.

II-VI was founded in 1971 in Saxonburg and remains headquartered there. It’s grown into a multibillion-dollar company with 24,000 employees in 69 locations across 14 countries, said Mark Lourie, vice president of corporate communications and brand development.

Named after columns on the Periodic Table of Elements, II-VI was started to design and manufacture infrared crystalline compounds primarily for high-power lasers used in materials processing.

II-VI was able to weather the region’s industrial collapse because it is more dependent on the global economy than the local economy, Lourie said.

“II-VI has grown to have thousands of customers worldwide in diversified markets,” he said.

Oberg Industries had 11 employees when it was founded in 1948 in Tarentum. Today, the precision stamp metal manufacturer has about 900 employees, including 650 at three plants in Buffalo Township, spokesman Ken Eck said.

Working across markets — automotive, energy, medical — helps Oberg “weather the economic downturns that can happen in those markets,” Eck said.

Among the larger employers in the area is Polyconcept North America, which many still know as Leeds or Leedsworld. A supplier of promotional products and corporate merchandise, it employs the bulk of its 2,000 employees, about 1,300, at its headquarters in the Westmoreland Business and Research Park in Upper Burrell and Washington Township, company President David Nicholson said.

Polyconcept, founded in 1986 in Murrysville, moved to the business park in 1998. Its revenue grew from under $100 million in 1998 to more than $500 million today.

The workforce is the primary reason why the company is here, Nicholson said.

“The community has been a terrific source of passionate and loyal employees. They’re a big part of our success,” he said. “We draw a large portion of our employee base from a lot of the steel communities. It’s been successful for us finding folks out of those industries who wanted to stay in the area. We’re fortunate to be able to offer opportunities so they can continue to live where they live and have a good place to work.”

The majority of the company’s products are made outside the United States, with the final decoration and fulfillment done here, Nicholson said.

“We view our business as a service business more than manufacturing,” he said. “Our types of business have thrived while traditional manufacturing has had difficulties.”

Polyconcept was the third business when it moved into the business park; now, it’s full with more than 25, Nicholson said.

Siemens employs 500 at its facilities in the park, where it engineers, produces and sells medium voltage drives used in several industries, including oil and gas and power generation. The business, formerly known as Robicon, was founded in 1964 and acquired by Siemens in 2005. The current facility was built in 1995 and expanded in 2006.

The rise of industrial parks

Business and industrial parks, where a number of businesses are clustered, are present in each of the Alle-Kiski Valley’s four counties.

Alle-Kiski sites that once had one large industrial employer are being redeveloped with multiple, smaller businesses with a technology focus.

More than 3,000 people work in businesses at four industrial or business parks in Armstrong County, said Mike Coonley, executive director of the Armstrong County Industrial Development Council.

Most of those people, about 2,000, work at West Hills Industrial Park. Others are Northpointe, Parks Bend Farms Industrial Park and Manor Business Park.

“The parks, themselves, were primarily developed to accommodate light manufacturing and service-oriented businesses and both remain important,” Coonley said. “Tech and data management have begun to have a larger presence, especially as the lines between ‘tech,’ data management and manufacturing have begun to blur and advanced manufacturing becomes increasingly important.”

In Butler County, Victory Road was built on the site of a former steel plant in Clinton Township. Started in 2001, it is home to 19 businesses employing more than 600 people, said Marcie Barlow, spokeswoman for the Butler County Community Development Corp.

The park was a Keystone Opportunity Zone, which gave tax incentives to the businesses that located there. That designation ended in 2017, and all of the businesses are now on the tax rolls, Barlow said.

Aldi’s eastern distribution center is located at Victory Road; Brayman Construction is another large tenant.

“That park has been a very successful park for the CDC, Clinton Township, the school district and Butler County,” she said. “The businesses that are there generate more than $1 million a year in taxes.”

The park’s location is a big reason for its success, Barlow said.

“We have a skilled workforce that meets the needs of the employers in that area,” she said.

Allegheny County Economic Development doesn’t own or operate industrial parks like the other counties do, said its director, Lance Chimka.

The closest version it has, Chimka said, is the Regional Industrial Development Corp. The RIDC business park in O’Hara, its first development, has served as an incubator “for really great companies,” he said. Once a 700-acre farm, it is home to more than 130 companies and thousands of jobs.

The RIDC’s tenants reflect the region’s shift away from a heavy manufacturing base to a more tech-centric, research and development, and light industrial economy.

“The employment base is every bit as large as what was once there before,” he said. “The new challenge is: How do we address the skills gap? How do we equip people with new and different skills and allow them the same kind of income opportunity people had entering the mills?”

Toward that, Siemens partners with Kiski Area High School to enhance the district’s science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) curriculum “to reflect the realities of today’s changing workplace,” spokeswoman Caroline Cassidy said. “Siemens is committed to continue this partnership for the next five years.”

Towns were once built around one, large industrial user. Such projects are very rare these days, Chimka said.

“It requires a lot of creativity to think about what a town looks like without that dynamic,” he said. “Towns that have been successful have viewed that exodus of large, heavy industry as a redevelopment opportunity.”

The A-K Valley: Cool & quirky?

Rising costs in Pittsburgh are driving growth farther from the city, particularly in the lower Allegheny Valley towns of Millvale, Etna and Sharpsburg, Chimka said.

“Lease rates are getting really high for the region. You can stand at one shore of the Allegheny and have $40-per-square-foot rent and look across and see $20-per-square-foot rent,” he said. “That’s driving some demand in the Allegheny Valley. You have proximity to talent and the research engine of the universities at a lower price point.”

Towns such as Tarentum and New Kensington are perfect examples of redevelopment opportunities, Chimka said.

“A lot of what’s driving it are the amenities. You find those in some of these older towns,” he said. “They’re cool and quirky places — every bit as much as the Strip District and Lawrenceville. Talent wants to be in and among coffee shops and breweries and sandwich shops. I’m feeling very optimistic about all those towns up the Allegheny.”

In moving forward with a new location in New Kensington, Voodoo Brewery partner Jake Voelker said they found a community interested in doing new things and changing the perception of the city.

“We saw a fully engaged community where we can have a lot of good impact,” he said. “The Alle-Kiski Valley has a lot of opportunity. We’re excited to be a part of that.”

Back in Gilpin, Len Kalmar’s Chevy dealership employs about 21, down from a high of 30. But he says there is still enough people and business to keep the dealership running into a third generation of his family.

“We have no plans to do anything but keep on going here,” he said.

Brian C. Rittmeyer is a TribLive reporter covering news in New Kensington, Arnold and Plum. A Pittsburgh native and graduate of Penn State University's Schreyer Honors College, Brian has been with the Trib since December 2000. He can be reached at brittmeyer@triblive.com.

Remove the ads from your TribLIVE reading experience but still support the journalists who create the content with TribLIVE Ad-Free.