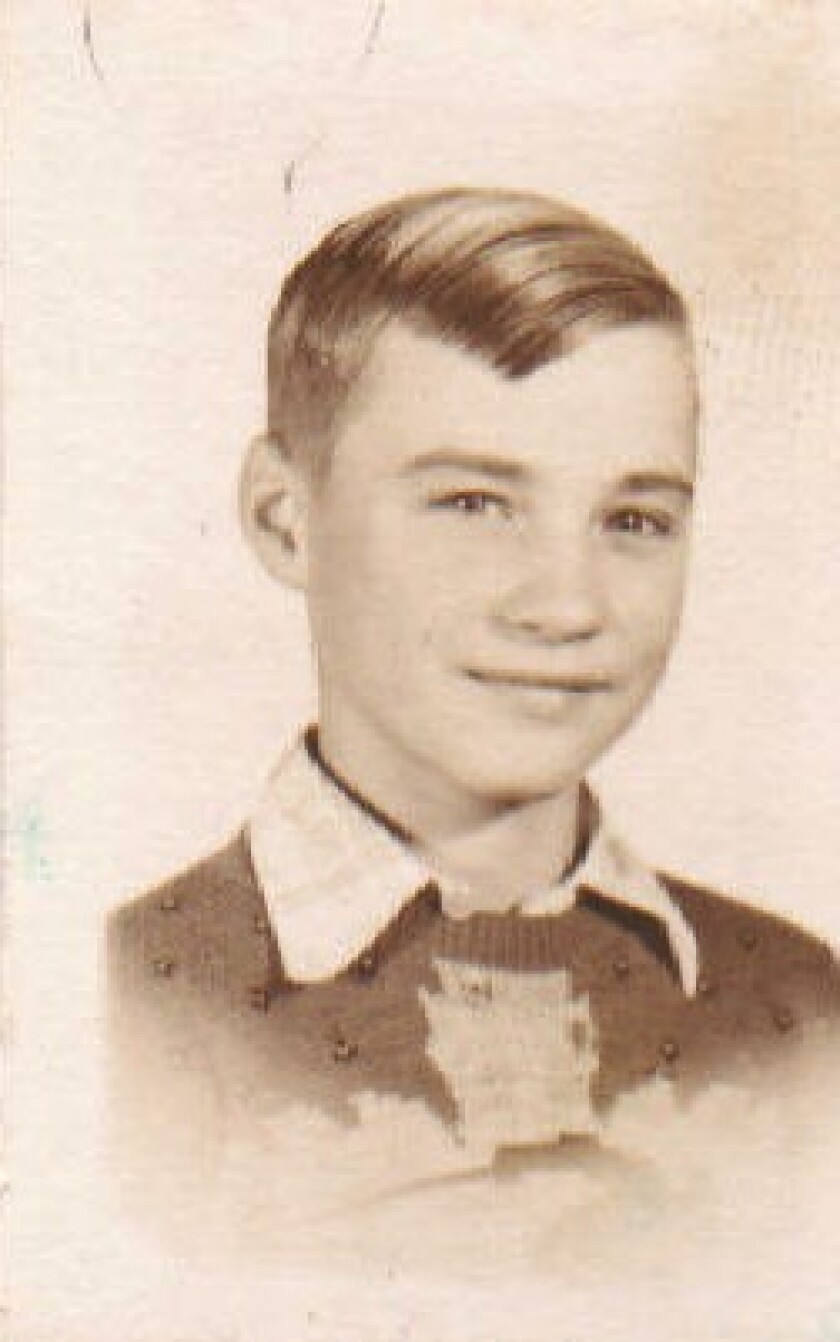

SELFRIDGE, N.D. — For decades, Ted Becker frequently woke up in the dead of night gagging. Sometimes a pungent, familiar smell would force him from bed to search the house for a repressed memory that took him years to find.

Not until he saw a psychiatrist in the late 1980s did he understand why the recurring sensations affected him so deeply. Memories of sexual abuse involving a Catholic priest from the early 1950s, beginning when he was 9 years old, flooded back.

Becker, now 82, said the post-traumatic stress he’s endured for the past 70 years came from the Rev. Victor J. Heinen of St. Philomena’s Catholic Church in Selfridge in south-central North Dakota.

Heinen’s predatory abuse lasted about three years, Becker said. All the abuse Becker remembers happened inside the priest’s house, usually the night before Sunday Mass. Heinen died in 1953.

ADVERTISEMENT

Becker has been searching for healing since the nightmares began. He and other North Dakota survivors of clergy sexual abuse want justice. They want the Roman Catholic Church to admit wrongdoing, to become completely transparent with the public and for bishops to be held accountable if they covered up abuse.

But so far, that justice has evaded Becker.

North Dakota Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem's office announced this month the results of an 18-month-long criminal probe into allegations against at least 54 clergy members accused of sexual abuse of minors since the 1950s. Stenehjem determined no charges would be filed because most of the accused clergy had died before the investigation was completed. For the others, the statute of limitations had expired.

Stenehjem said the investigation included cooperation from the Bismarck and Fargo dioceses, which made their lists of accused clergy public in January 2020.

Had the statute of limitations not run out, Stenehjem said charges could have been brought against one priest in the Bismarck Diocese and another at the Richardton Assumption Abbey, which is not under the jurisdiction of either diocese. No clergy from the Fargo Diocese were named as potential defendants, and no additional Fargo clergy were found by the state Bureau of Criminal Investigation to be sexual predators.

The Bismarck Diocese declined to comment for this story, and the Fargo Diocese declined a request for an in-person interview, but Fargo Bishop John Folda did answer questions via email.

Folda insists that he has reported abuse upon learning of it. "Accountability is accomplished, first, by immediately reporting to law enforcement officials and, second, by our own zero tolerance policy," Folda wrote. "The last three popes have tightened standards of accountability, and this past year Pope Francis required a national system of reporting for sexual abuse or cover-up of abuse by bishops."

ADVERTISEMENT

Becker expressed disgust over Stenehjem's investigation after hearing that no clergy would be criminally charged.

“What we’re taught is that religious persons are one step above the average man. Here, they are 25 steps behind,” Becker said.

Stories about boys abused by Heinen and other pedophile priests slipped through at intervals while Becker recounted his own life’s story. As a younger man, when he was active as a lay minister at St. Joseph's Catholic Church in Williston, he said he knew of at least six priests from the Bismarck Diocese who faced accusations of sexually abusing children. Five of their names are on the Bismarck Diocese list, including Heinen.

“I would like to see 100% transparency," Becker said, adding that he would like the diocese to reach out to him "and all of us boys who are still alive and say ‘Ted, we would like to help you, and will you accept help from us?’”

After decades of struggling with trust issues, Becker has found his own methods of healing. Talking about his trauma is his therapy.

Investigating predator priests

The Fargo and Bismarck lists of accused clergy do not include what abuses occurred, how many children were harmed, the age of the victims when the abuse happened, where accused clergy worked or where they are now. Both dioceses declined The Forum's requests for more information about the clergy on the lists and the allegations against them.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Fargo Diocese said it does not comment on individual cases. "Because suffering abuse and bearing witness is difficult, it could have a chilling effect on people coming forward if we published the details of their allegations and testimony," Folda wrote.

The Forum’s investigation found at least four accused Fargo Diocese clergy were still alive and not convicted in court. The online trails for other priests led to sexual abuse criminal trials, which included victims as young as 5 years old.

Based on the lists, only three clergy members who faced allegations while serving in North Dakota were imprisoned. One was Fernando Sayasaya , who was sentenced in 2018 to 20 years in prison for abusing two boys in the 1990s in Fargo and West Fargo .

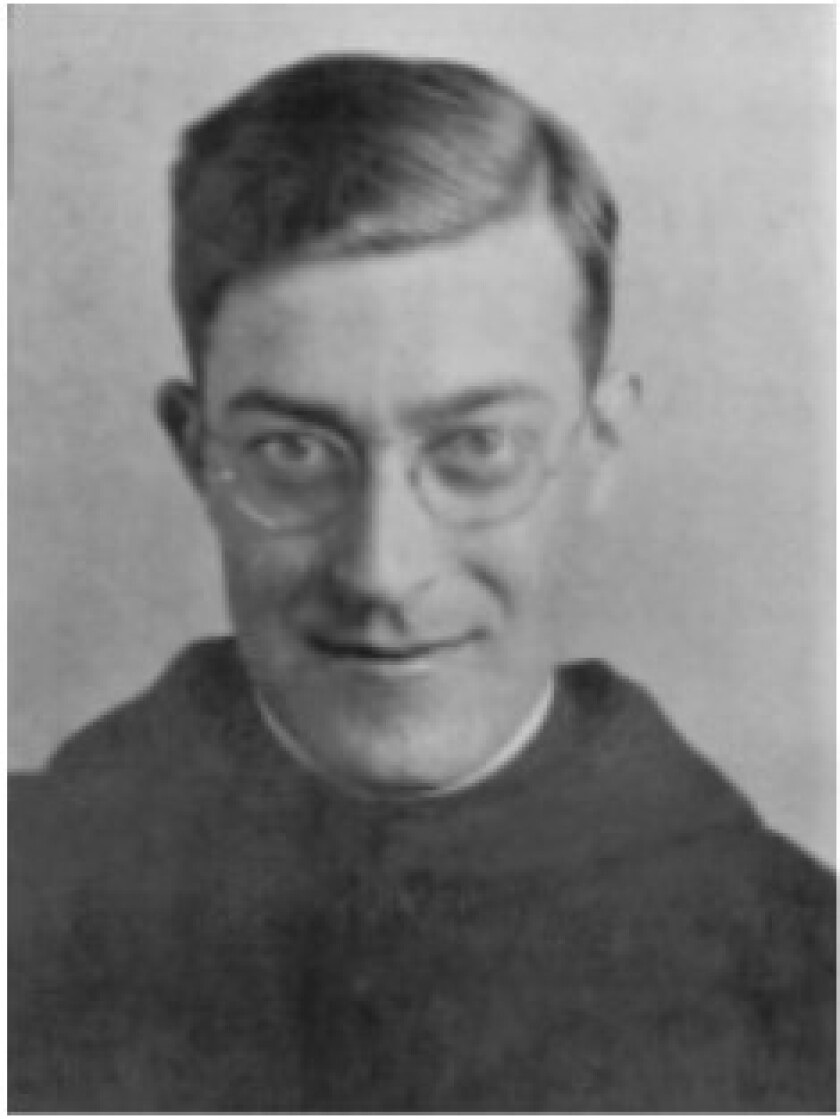

Some clergy, like Heinen, were sent to retreats that were used as recycling centers to launder pedophile priests, places like the Blue Cloud Abbey in South Dakota and the Servants of the Paraclete, which for decades was a treatment center in New Mexico.

Deacon Alan Storey in Walhalla was charged in 2003 with alleged sexual assault of a young girl at his home during a funeral in 2002, according to court documents. The case was dismissed on the condition he complete treatment, court documents said. Storey also was removed from the clergy, the diocese said. Storey declined to comment for this story.

Other trails led to secret settlement agreements. Such agreements have often left victims silenced and sometimes suicidal, according to Thomas Doyle, an ordained priest and an expert witness in hundreds of Catholic clergy sexual abuse cases around the world.

ADVERTISEMENT

For many survivors like Becker and canon law experts like Doyle, the lists produced by the dioceses of Fargo and Bismarck offer too little, too late. “The lists in most cases are not complete. You can’t count on the bishops to shoot straight, ever," said Doyle of most Catholic lists of accused clergy that he’s researched.

In Fargo, Folda said he ordered a review of files to identify substantiated sexual abuse claims against clergy shortly after he became bishop in 2013. The review turned up more than 1,000 files dating back 70 years, which is why it took so long, he said.

The bishop said the end of Stenehjem's investigation confirms the diocese has a complete list. New names will be added if future claims are substantiated, Folda said.

To prevent further sexual abuse, the diocese has implemented several efforts, including training and background checks. "We will not relax these efforts because, as I’ve said before, even one instance of sexual abuse of minors is too many," Folda wrote.

The Fargo and Bismarck dioceses said on their websites that sufficient corroborating evidence must exist to establish abuse happened. It may not be enough to get a conviction in court, but criteria may include firsthand testimony, the accused admitting the allegations, multiple allegations that show a pattern of sexual behavior and prior grooming efforts.

“When they publish the lists of what they call credibly accused, there is a positive effect that it tells the victims that yes, this really did happen, and it also brings out other victims,” Doyle said. “But one of the reasons we’re in this huge mess worldwide is because bishops have been trying to handle all this themselves.”

Terry McKiernan, founder of Bishop Accountability, an organization that compiles data on pedophile priests, was critical of the North Dakota dioceses' lists. “One thing that is disappointing is that they are not giving us a lot of information about these guys,” McKiernan said. “Many churches provide a history, but Bismarck and Fargo are not only very late, they are behind the curve.”

The lists leave multiple questions unanswered, McKiernan said.

ADVERTISEMENT

"There is so much more to know about the men that are listed on these lists," he said. "Who knew about the abuse then? Are there church managers that need to be held to account because they allowed this to happen?"

The North Dakota Attorney General’s Office declined to comment on the question of whether Catholic leaders should be held accountable.

When asked if the attorney general's office is investigating allegations that the dioceses protected priests, office spokeswoman Liz Brocker said "failure to report child abuse is a misdemeanor," but the statute of limitations for that crime is two years.

"The allegations were all reported more than 2 years ago," she said, not elaborating, but seeming to suggest that no one in the dioceses will face criminal charges if they covered up allegations of sexual abuse of minors.

Fargo Diocese spokesman Paul Braun said the diocese has followed reporting requirements and will continue to do so.

'I don't hate the guy'

One name on Fargo’s list of accused clergy stood out to McKiernan: Gregory (Zbigniew) Patejko. For decades, McKiernan has known a survivor of Patejko’s abuse.

ADVERTISEMENT

In 1976, when Richard Jangula was 18, he met Patejko on a flight from Denver to Bismarck. Jangula accepted Patejko’s offer for a ride home and was sexually molested on the way, he said. Patejko worked at St. Andrew’s Catholic Church in Zeeland at the time.

Now 63 years old, Jangula has recently returned to Bismarck from Florida. He’s legally blind, has stomach issues, even fought off cancer.

The one battle he can’t forget after 45 years is Patejko’s abuse.

The experience has not soured him against the Catholic Church. He has friends who are priests and nuns; his four children attended Catholic schools.

“I am still Catholic," Jangula said. "The priest that did that to me … I don’t hate the guy. I forgave him the day after it happened, but it’s like, why don’t people realize that we, too, feel shame?”

McKiernan, Jangula’s longtime friend, said he read the Bismarck list to Jangula over the telephone when it first came out.

“I recognized about six names,” Jangula said. “The Vatican won’t do anything about it. It’s never known if they’re really guilty.”

Jangula’s abuse continued twice more, and at the time he didn’t tell his family. Later in life, he settled with the Catholic Church for $34,000 in medical expenses and $6,000 for psychological help, Jangula said.

Five years after the abuse, Jangula was hospitalized with stomach issues. Only after doctors checked him out did he discover he had three ulcers.

“I didn’t know how to handle it. Who could I talk to?” Jangula said.

'God was going to punish me'

Debbie Bjorem used to get triggered when she passed the church building where she said a priest sexually abused her as a teen. The building no longer stands, but the 58-year-old from Fargo said she still gasps sometimes as she goes by.

Bjorem said she did not report the abuse immediately for several reasons. “I thought that if I said something, God was going to punish me more because I touched a chosen person,” she said.

After decades of trying to process what happened, she reported the priest to the Fargo Diocese. Accompanied by diocese staff, she went to the Fargo Police Department with her story, though charges were never filed. The Forum is not naming the priest since he was not arrested or criminally charged.

The diocese investigated the priest and banned him from performing priestly duties, but he was not added to its list of accused priests. The diocese declined to speak about the allegations. The Forum's attempts to reach the priest by phone were unsuccessful.

Bjorem praised the Fargo Diocese for investigating her claims, noting that one church official said he believed her from the beginning. He assured her the priest, not her, was in trouble, she said.

She said she is fine with the priest not being on the list. She just wanted an apology, which she said she never got from the priest.

She said Folda is left to clean up a mess and is trying to do his best. Not all priests are bad, she added.

Glimmer of hope

Years ago when Becker tried to report Heinen’s abuse, he was ignored.

“I wrote a letter to the bishop of Bismarck about the whole thing, outlined everything, and I got this lovely letter back thanking me for the letter and expressed deep sorrow for the trauma, blah blah blah … and that’s it,” Becker said.

In the 2002 letter, then Bishop Paul Zipfel wrote back to Becker saying he found no records of complaints against Heinen. Zipfel died in 2019.

“The present bishop of the Bismarck Diocese released a list of priests who were alleged to have sexually abused boys,” Becker said. “How could he include Heinen's name in the list if what Zipfel said in his letter to me was true?”

The Vatican now requires bishops to report all cases of sexual abuse to civil authorities, Doyle said, which in the U.S. would include child protection services and law enforcement. Historically, cases of sexual abuse were handled within the church.

Denver Archbishop Samuel Aquila is the only past bishop from North Dakota who is alive today. He served as the Fargo bishop from March 2002 into July 2012, preceding Folda. The Forum sent a list of questions to Aquila's spokesperson and requested an interview with the archbishop, but Aquila did not answer the questions or grant an interview.

Folda said he and Aquila reported abuse upon learning of it, though the current bishop noted he didn't have information on how past diocese heads handled child sex abuse allegations. "We have much more information today than they did, and it seems that people are more willing to come forward now than in the past," Folda wrote.

The diocese has a victim assistance coordinator to help victims report claims of abuse, as well as connect them with resources such as counseling. "We cannot change the past, but we are determined to ensure that sexual abuse of minors does not occur and is not tolerated in the Church," Folda wrote.

Bipartisan bills being floated in North Dakota's legislative session this year could offer survivors some hope of pursuing legal action in civil court, despite existing statutes of limitations.

Becker and the other survivors The Forum interviewed do not plan to pursue any future litigation. But if passed in North Dakota, the bills would offer survivors a two-year window to file sexual abuse lawsuits in civil courts, said Rep. Austin Schauer, R-West Fargo, who wrote the bills along with input from Democrat Sens. Kathy Hogan and Tim Mathern, both of Fargo. Other states, including Minnesota, have passed similar legislation.

'All I wanted'

Both Becker and Jangula learned as children never to question the church. To Becker, priests were on a pedestal.

“Children, they looked up to this guy as yeah, one step below God on the ladder,” Becker said.

Former friends and neighbors told Becker about being abused by Heinen, he said, and some of the other survivors referred to themselves as the “Heinen 12.” Today, only Becker and one other are still alive, he said.

“As boys I don't believe we knew there was even one other boy that was being abused," Becker said. "I just know that I did not talk with anyone about it."

Somehow, his parents discovered Heinen’s abuse.

In April 1951, his mother told him to go see his father in the basement. It was there that Becker said his father’s question left an indelible imprint on his mind.

“He was working on the furnace. He stopped. He asked me a direct question: 'Did Father Heinen make white stuff come out of your pee pee?'"

“And I said, 'Yeah.' And he said, 'Are you sure?' And I said, 'Yeah, so what.' And that was it.”

After that day, Heinen’s abuse was never brought up again. Even as the gossip spread around town, his parents never spoke to him about the abuse, Becker said.

“It was Dad who came in, took care of the problem, over and done with and you don’t talk about it,” Becker said.

Three days later, Heinen was sent packing for Missouri’s Benedictine Conception Abbey, but not before he molested Becker once more.

Jangula was raised much the same way as Becker.

“In our family and our culture where we grew up, Catholicism was everything. I remember when some of my relatives thought I went blind because of me going public," Jangula said. “The Catholic Church and others said that it’s people like me who destroyed the church. They didn’t have to close the parishes, I never sued them, but if I hadn’t agreed to the $34,000 (settlement) they would have never acknowledged that it had happened.”

Acknowledgement. “That’s all I wanted,” Jangula said.

Patejko died in 1996 after returning to Poland, his birthplace, according to the Fargo Diocese.

“It’s the church who should be ashamed, not us,” Jangula said. “I don’t want people to hate priests. To me, my religion is my faith, and I would not wish my life on anybody, but I thank God every day for the way I am. Sure, I wish it was a little better, but he has a plan for me.”

How to report abuse

If you or a child are in immediate danger, call 911.

To report sexual abuse to the North Dakota Attorney General’s Office, email ndag@nd.gov or call 800-472-2185. Abuse also can be reported to the National Child Abuse Hotline at 800-4-A-Child or by visiting childhelp.org/hotline .

To report abuse to the Fargo Diocese, call 701-356-7965. More information on victim assistance can be found at fargodiocese.net/victimassistance .

To report abuse to the Bismarck Diocese, call 877-405-7435 or 701-223-1347. For more information, go to bismarckdiocese.com/victim-assistance .

Forum News Service reporter Sarah Mearhoff contributed to this report.