I used to think I was pretty great at French: I could handle a subjunctive and disdained the myriad mangled pronunciations of “millefeuille” on Masterchef. I lived in French-speaking Brussels for 12 years and have a French husband who still tolerates me misgendering the dishwasher after 24 years. My inflated sense of my abilities was bolstered over the years by compliments from surprised French people. Admittedly, the bar is pitifully low for Brits speaking a foreign language: like Samuel Johnson’s dog walking on its hind legs, it’s not done well but people are surprised it’s done at all.

In recent years, however, I have let things slide. My French has become trashy: it’s the language of reality and cooking shows (my staple French televisual diet) and easy chat with indulgent friends. I fear I speak French like Joey Essex speaks English, and since we moved back to the UK this year things have got worse. My only French conversation here is with my husband and it runs a well-worn course: who should empty the bin; why we have no money; which of our teenage sons hates us more. When I try to express something complex, I get stuck mid-sentence, unable to express my thoughts clearly. Words that used to be there, waiting to be used, are awol and I have developed a horrible habit of just saying them in English. My husband understands, so who cares?

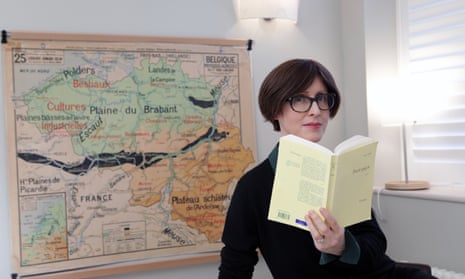

But I care. I can’t bear to lose my French; it’s part of who I am. I even wrote a book about it, for God’s sake. I want to speak the language of Molière, if not like Molière then at least like a reasonably articulate adult. So I resolve to not just stop the rot but reverse it. This will involve a multi-pronged approach: online lessons plus conversation classes, supplemented by a diet of French podcasts and reading, including my third attempt at Les Misérables.

Au boulot – to work!

Week one

I take the Institut Français’s online test to check my level. It doesn’t seem difficult but my result – “first step to C1” – is mortifying. I assumed I had C1 (the second-highest level of European official language qualification) in the bag, but if this test could talk it would be saying: “Bof.”

My first online lessons cheer me up: Frantastique (a learning platform developed with the Institut Français, tagline: “Surrender to French”) is a riot. In my first session, I watch a short cartoon in which anarchic aliens incomprehensibly revive a naked, frozen Victor Hugo (beard preserving his modesty), after which I answer grammar and vocabulary questions about it. I enjoy it so much, I do seven lessons in one sitting: Victor visits the alien canteen, but the lack of mustard makes everyone so angry they head to Earth to find more. I’m not sure what I’ve learned – aliens love mustard? – but I’m keen for more.

One-to-one conversation classes at the Alliance Française (which has the mission of promoting French language and culture abroad) are a more serious affair. Christine Grimaud-Brown, my teacher and the director of the York branch, sends me an article on the 21st-century perception of time, no less, to prepare for our first session. It starts off as a relaxed chat and Christine doesn’t correct my mistakes (I secretly yearn for this), but we soon get into fairly abstract territory and speaking to a stranger makes me raise my game. I can tell this will be useful.

For extra speaking practice, I try the Alliance Française’s Café Conversation, a twice-weekly chat for French speakers, with a native facilitator. Anything goes, topic wise: on my first session, we cover cricket (including whether French has a word for “wicket”), pantomimes and green energy; later discussions range from Alzheimer’s to cemeteries and Christmas cake. Levels vary although, broadly, the demographic is at the upper end of the scale: my French is tested explaining “piñata” (“a paper animal in which sweets are placed. One strikes the animal with a stick”) and “Hamilton” (“a popular musical of the American revolution utilising le rap”) to other attendees and to universal confusion. I love it, though, and show off dreadfully.

On my morning dog walks, I plunge into the rigorous world of Le Nouvel Esprit Public, a geopolitics podcast featuring the kind of French intellectuals who would dip Melvyn Bragg in their café au lait and eat him for breakfast. They speak in fluid, impassioned sentences about the US midterms or the Italian budget. It’s exactly the kind of French I aspire to. I also enjoy Passions Médiévistes, in which medievalists describe their esoteric research, but it precipitates a minor existential crisis: why aren’t I researching dragons in medieval prayer books? “J’ai raté ma vie,” (my life is a failure) I mutter, Frenchly.

Week two

Frantastique continues to entertain: Victor Hugo throws a wild party and the aliens hold a pro-mustard demo (“Liberté, Fraternité, Moutarde,” reads one placard). Regrettably but predictably, I have become obsessed with my marks. The questions aren’t difficult but I keep making stupid mistakes, to my own fury. Occasionally I feel hard done by: one afternoon my husband comes home to find me incandescent, brandishing a screengrab of a wood-burning stove.

“What’s this?” I hiss angrily.

“Er, un poêle?”

“It’s not a four is it? I lost a mark for not calling it an oven!”

My conversation class with Christine is about art, so I read the heap of articles she provides, then write an excruciatingly bad essay. It reads like the work of a pretentious but dim 12-year old. “What is art?” I say clunkily, before attempting to describe a Marina Abramović performance (“She washes the bloody bones of a cow for three days”), giving myself the giggles. In class, though, I really enjoy our discussion, and occasionally feel my lazy synapses creak into action, finding the right word or expression.

My reading is patchy. Gaël Faye’s excellent novel Petit Pays, about the genocide in Burundi, teaches me “threadbare”, “calabash” and “serval” (admittedly, I don’t know what the last two actually are). Les Misérables, however, induces instant deep sleep and – now that Frantastique has transformed Victor Hugo into a tiny, naked sex god in my mind – floridly peculiar dreams.

Week three

I test some new podcasts, including Vieille Branche, a series of interviews with older, outspoken and fascinating French public figures (I especially enjoy 88-year-old S&M mistress Catherine Robbe-Grillet). At the other end of the spectrum, I fall in love with Entre: tender, funny conversations with Justine, a sparky and delightful 11-year-old grappling with school, friendships and family. Each episode is five to 10 minutes long, perfect for learners.

In class, we discuss fake news. I feel relaxed talking to Christine, but I notice she has a skilful way of pushing me into expressing more complex ideas with her questions. “Does society still care about truth?” she asks. Or: “Is national character a product of language or vice versa?” Sometimes I answer fluently; sometimes I end up stumbling and stuck.

There are signs of progress. I finally stagger up a level on Frantastique, despite my constant blunders. At Café Conversation, in my capacity as class swot (fayot), I am asked to translate “pick your brain”, “quirky” and “allotment” and as I slalom between shoals of tourists when I leave, a hissed “Pardon” comes to my lips rather than the usual Yorkshire tut.

Week four

My Frantastique experience draws to an ignominious close as I cravenly resort to cheating on the spelling of “environnemental”. Worse, I get 47% one day, due to my apparent inability to follow simple instructions conjugating the imperfect. I will miss Victor, and Gérard, a drooling, mustard-crazed alien blob on whom I have a bit of a crush.

Has my French improved? My general knowledge certainly has: I know more about Breton medieval government, the artist Paul Sérusier and Armenian politics than I ever anticipated. On one glorious occasion in class, I supplied a word Christine had forgotten (“légiférer”, legislate). I have barely started Les Misérables, but already have some vocabulary that would be handy if I were a low-ranking cleric in Restoration France.

Even so, when I retake the Institut Français test, I get that maddening “first step to C1” again. J’suis dég, as I would say in Joey Essex French. I’m gutted, but I shouldn’t be. “At your level, progress is much more subtle,” Christine reassures me. I do think something has started to shift: now when my husband and I watch the news, I find myself moved to launch into fluent sentences of Gallic vitriol at the sight of Jacob Rees-Mogg rather than Anglo-Saxon expletives. Better still, I have been powerfully reminded what I love about France and French: that fiercely cerebral public culture and the sheer beauty of its words. In one podcast someone casually uses “lacustre” (lacustrine, meaning of or relating to lakes); it’s so lovely I have to stop and write it down. By Victor Hugo’s beard, I will rise above my trash French and become the kind of person who says lacustre.

How to sound ‘with it’ in French …

From vloggeuse to startupeur or swag, most “hip” French words are English ones: chatbot, queer and cosplay all entered the Petit Robert dictionary this year. But here are a few that keep a Gallic flavour.

Mecspliquer To mansplain. A mot-valise (portmanteau word) composed of mec (guy) and expliquer (to explain).

Lourd Literally “heavy”, and generally used to mean tiresome, but now, in an adult-bamboozling plot twist, it means good, pleasing. C’est du lourd or ça envoie du lourd = it is impressive. The verlan (backwards slang) version, relou, is still used to mean annoying, or a pain. All clear? Clair comme de l’eau de boudin (as clear as black pudding water, another great expression).

PTDR Pété de rire, literally “broken with mirth”, the French LOL. Although, of course, most French people use “LOL”.

Pécho To seduce, get together with, hook up. Verlan of choper (to seize or get).

J’ai le seum I am displeased/angry/disappointed.

J’ai failli pécho ce gars, mais il a commencé à me mecspliquer ma propre thèse doctorale. C’est archi-relou, j’ai le seum. I nearly hooked up with this guy, but he started to mansplain my own PhD thesis to me. It’s such a pain, I’m gutted.

… and how to sound like an intellectual

Give your conversation a soupçon of Left Bank va-va-voom.

Langage épicène Also known as écriture inclusive, this controversial but increasingly popular typography style uses a point médian, a sort of decimal point, to create gender-neutral nouns. So a person reading this would be un·e lecteur·rice and the person writing it would be be un·e journaliste (or un·e idiot·e). Last year the French prime minister, Édouard Philippe, banned the point médian in official documents with an inflammatory declaration that “the masculine is a neutral form”.

Jupitérien From Jupiter, king of the gods. Applied to Emmanuel Macron’s presidential style (he used the term to contrast with the more down-to-earth approach of his predecessor, François Hollande), it implies a degree of deliberate distance and grandeur and is now used by his critics to suggest he is haughty or arrogant. Telling a teenager to call you “Monsieur le Président” = jupitérien.

Cartésien My go-to word to sound intelligent in French. Derived from philosopher René Descartes, it’s used generically to mean “logical” or “rational”. Du point de vue purement cartésien (from a purely rational perspective) is a good (inflammatory) start to a sentence in a French argument.

Charge mentale Mental load or burden. A hot topic of feminist debate following the publication last year of cartoonist Emma’s Fallait Demander – You Should Have Asked – on women’s experience of continually having to anticipate and meet their families’ myriad needs. The Twitter account @chargementale collates some of the most egregious examples of paternal ineptitude encountered by doctors in French paediatrics.

J’ai commencé à voir tout le temps des crabes autour de moi I started to see crabs around me all the time. Not an everyday expression, but handy if you wish to reproduce Jean-Paul Sartre’s ill-advised 1970s experiment with mescaline. Life as a French intellectual is a dangerous business.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion