The Best Losers in America

Forget the Lions or the Clippers or even the Knicks. No team in all of American sports is better than the Mets at being the worst.

The sight of Ray Knight rounding third base with the winning run of Game 6 in the 1986 World Series against the Boston Red Sox—completing a two-run, two-out, two-strike comeback in the bottom of the tenth inning—was the greatest moment of my life, and I have two kids. I will cherish the memories of my sweet, gorgeous, magical children drawing their first breaths until the day I draw my last. I’ll just cherish them ever so slightly less than my memories of that Game 6.

I was 10 years old, and it was after midnight, and I’d already bleated so many times during the first nine and a half innings that I was under penalty of death if I woke up anyone else. By the top of the tenth, the noises coming out of me had turned dark and guttural. The Mets were down three games to two. A loss here tonight would end the series, and my childhood. Then right away in the top of the tenth, Red Sox outfielder Dave “Hendu” Henderson, who’d crushed us that whole series, crushed the second pitch so hard off the facade above the left-field wall that it ricocheted 50 yards back into left-center.

He hit that ball so hard that its essence went clean through my chest, and I didn’t feel it until I saw the baseball-size hole where several of my vital organs used to be. Phonetically, the sound I made was nngyuuuh. It was the sound of a 10-year-old boy learning that life is shit. Boston up 4–3. And then, as the light in my eyes went out, Sox third baseman Wade Boggs clubbed a double in the gap, followed by light-hitting second baseman Marty Barrett singling him home—Barrett’s 12th hit in six games, lifting his World Series batting average to .418. Boston up 5–3. Game over. Childhood over.

Knowing what I know now, about life, about losing, about giving your heart to a team like the Mets, I ache for those Red Sox fans, belligerent and insufferable as they were, because here we are all these decades later, and they’re still haunted by the sight of Mookie Wilson’s hard grounder sneaking through Bill Buckner’s legs. The late, great Shea Stadium was built on a fetid ash heap, and it took just 12 minutes for the Mets to rise from it, roar back, and win the game, 6–5.

As I processed what was happening, I uncorked one of those silent shrieks where you’re going berserk but no sound is coming out. The clashing forces of the air trying to leave my body and me trying to hold in the sound caused a sudden rush of oxygen into my head. I remember the feeling of my brain expanding in my skull and getting super warm as Ray Knight stomped on home plate, and I know for certain that if it happened again today, I would stroke out.

So many baseball fans I know have heartwarming stories about how they fell for their favorite teams—a family saga, an iconic moment to which they bore accidental witness. For me, a key factor was color schemes. The Yankees were drab and gray. They radiated no fun. The Mets were orange! And blue! And the NY on their caps sprouted soft round serifs, like muffin tops. The Yankees logo was all sharp elbows, and didn’t anyone else find it unsettling that their pinstripes looked like prison uniforms? Like they were playing for their lives? My parents both grew up in the Bronx, an irony I’ve always savored, but they split up when I was 6. By the time I fell for baseball, I was seeing my father only a few times a month, which was sad for my childhood but a godsend for my baseball future because it liberated me to choose my own destiny. I can see clearly now that baseball was a balm for loneliness, a way to be in the company of men and learn codes and rituals and feel a part of a group, however vicariously. In the real world, I didn’t know anything about men and didn’t get to spend much time in their company. I learned about men from baseball.

I learned, God help me, from the Mets.

I’d like to think that the Mets chose me, in recognition of a kindred spirit, as much as I chose them. What really clinched it, though, wasn’t my ardor for their Day-Glo colors, or my sense that I’d found my tribe. If I drew up a pie chart, those factors would take up about 25 percent. The other 75 percent, the No. 1 overwhelming reason I’m a Mets fan, is that I was 7 years old and the Mets had a player named Strawberry. That’s really all it took.

The 1986 Mets had a warping effect on my psychology as a Mets fan, imbuing me with a capacity for endlessly self-replenishing optimism even when it was unwarranted. (It was always unwarranted.) When I’d first fallen in love with baseball a few years earlier, the Mets were emerging from one of their most brutal stretches as a franchise, but I didn’t know about any of that. I just knew they were bad. I’d watched the grainy footage they always showed on WWOR during rain delays, of Casey Stengel in his inflatable Mets uniform doing his stand-up act. I knew about 1962, the worst team there ever was. I knew about 40 wins and 120 losses. But I was far too young to grasp how rare and special the Mets’ 1986 season was. It’d been 13 years since their last trip to the World Series, in 1973, when they lost to the dynastic Oakland Athletics in seven games, but I knew there were plenty of fan bases that’d been waiting far longer, including some that’d been waiting forever. Besides, for as long as I’d been watching baseball, the Mets had been good. My first three seasons as a fan just so happened to coincide with the Mets’ first run of three consecutive 90-win seasons. As far as I was concerned, the 1989 season, when the Mets won just 87 games and finished second in the National League East, was a catastrophe. How naive I was.

I’ve never shaken it. Almost 40 years now, I’ve been like this—stupid, delusional—and I love it. It’s so much more fun than being one of those once-suffering Red Sox fans who don’t know what to do with themselves now that the Red Sox are the Yankees. But that ’86 team was also the beginning of my true education as a Mets fan, and the first lesson I learned was that 1986 was the anomaly—the one and only time in Mets history when the Mets were the juggernaut. Only in retrospect did it become clear what a bunch of drunks and criminals and ticking time bombs so many of them were, and how inevitable it was that they’d blow apart in spectacular fashion.

I didn’t have the wisdom to understand this at the time, but the World Series—the winning, the dominance, the champagne in the locker room—that wasn’t the Metsy part of the ’86 story. The Metsy part was everything that came next.

Most people in this world are under the impression that the Mets are a very bad baseball team, but this is not true. The Mets are not bad. Listen. They’ve been bad at times in the past, let’s call it more often than not, and they hold the MLB record for being bad the most times in a single season. But “badness” is not what defines the Mets as a franchise. There is a difference between being bad and being gifted at losing, and this distinction holds the key to understanding the true magic of the New York Mets. My Mets. Your Mets. The Mets in all of us.

You could lock every fan of the Texas Rangers, Seattle Mariners, and Colorado Rockies in a small storage locker, and they would kill one another for the Mets’ postseason history. In 57 seasons to date, the Mets have reached the postseason nine times, they’ve played in five World Series, and they’ve won twice. Yes, it’s been a while since 1986, and it’s probably true that half the people who had vivid memories of that season are now dead. Still, compared with the genuine sad sacks of pro sports, the fan bases with zero joy, no highs, all lows, nothing to show for their loyalty but a deep dent in their foreheads from slapping them for decades, the Mets’ track record for badness simply doesn’t rate. It’s pretty meh.

In fact, amazing and/or miraculous postseason runs are as much a part of the Mets’ identity as losing 120 games in 1962. For everyone who cares about the Mets, the DNA of seasons such as 1969, with the original Miracle Mets; 1973, when the “Ya Gotta Believe” Mets went from last place to Game 7 of the World Series in two months; and 1986, a season-long bullet train—right up until they almost derailed twice in the playoffs—has encoded in us this hapless instinct that a reversal of fortune is always possible. It’s happened before, and it’s happened more than once. It’s kind of our thing.

The mental state of your standard-issue Mets fan is to be simultaneously certain of humiliating defeat and pretty darn sure there’s a miracle brewing. It’s not bracing for the worst, exactly. It’s bracing for something. Something awful, surely … but maybe not! Mets fans have the capacity to believe in both outcomes with equal commitment. This is very hard to do. You probably couldn’t pull it off. You’d have to be special.

If choosing to live like this seems crazy to you, or masochistic, or maybe sort of pitiful, first of all, duh, but second of all, that just proves you don’t have what it takes to be one of us. You can’t do this shit without a sense of humor. “I know this makes no sense,” the comedian and ABC late-night host Jimmy Kimmel told me, “but I feel like Mets fans have more integrity than the Yankees fans.” Kimmel grew up in Brooklyn and came of age as a Mets fan in the mid-1970s, just as the core of the ’69 Miracle Mets was heading into decline. He laughed a mirthy Metsy laugh, the one we all recognize. “It’s the rooting-for-the-underdog mentality. Like, you could root for the Yankees, I guess, and win a lot. I don’t identify with that, and I think a lot of comedians probably feel the same way. Like, in my life, we’ve only won one time”—twice, technically; he was 2 in 1969—“and there’s a real strong possibility we’ll never win again. It’s part of the deal.”

There is no such thing as a funny winner. The Yankees have won more titles than any other franchise in sports, which is why the Yankees are the most humorless franchise in sports. Their fans don’t laugh; they snicker. The only funny Yankees fans alive, in fact, are Larry David, who was already 14 years old when the Mets came along (but still should’ve known better), and the Bodega Boys, Desus and Mero, who were raised in the Bronx, which is the only defensible reason to root for the Yankees, aside from family inheritance. Donald Trump grew up in Queens, and at some point he decided he was a Yankees fan. I rest my case.

“The Mets are losers, just like nearly everybody else in life,” Jimmy Breslin wrote in Can’t Anybody Here Play This Game?, the canonical sportswriter’s early comic snapshot of the Mets’ inaugural 1962 season.

There are no winners in this world, not really—just losers who haven’t lost yet, failures who haven’t embraced their fate yet. Winning belongs to the gods. Losing is for the rest of us. What is daily life, after all, but a series of tiny defeats? What is death but taking that one final L? Losing blossoms over time; the layers emerge; the stories get richer and more complex; the funny stuff comes out. Winning begins to degrade right away. Eventually all that’s left of winning is the distance from it, and that’s when it starts to turn sad and hollow.

If you’re dedicated enough to the craft, losing can approach something like the divine. A gift for losing fills every moment with magical possibility, and this is where the Mets really shine. It’s incorrect to say our dear boys invent new ways, because invent implies volition. The Mets discover ways to lose like the Titanic discovered an iceberg. That’s why the New York Mets are the best worst team in sports. Because when it comes to losing in spectacular fashion, no one’s ever done it better.

Now there may be some fans of trash teams out there who have read this far and who think I’ve been too cavalier in dismissing their body of work. They’re wrong, but I suppose they deserve a fair hearing.

The Detroit Lions might be the worst worst team in sports, which is to say: They’re not even good at being bad. They’ve never won a Super Bowl, never been to a Super Bowl. They’ve played (lost) in a conference title game once, and that was before we all had cellphones. I don’t have to consult the internet to know that the Lions have never had a memorable postseason moment—good or bad—because if they had, I’d remember it. It’s been nothing but decades of cold, slushy, uninterrupted losing. Even their uniforms, bluish-gray and grayish-blue, are colorless. Playing for the Lions is such a demoralizing experience that the two most gifted players in team history, running back Barry Sanders and wide receiver Calvin Johnson, both retired in their prime rather than spend another season with Detroit. They didn’t just quit the Lions, they quit football. They ghosted. After Johnson walked away in 2016, at age 30, the Lions’ front office demanded that he return a $3.2 million roster bonus, which is sort of petty for a team owned by the Ford family. It also means the Lions now have a frosty relationship with at least 50 percent of their franchise icons.

The Cleveland Browns have a better claim to the “best worst” throne, because unlike the Lions, they are easy to like, and unlike the Lions, their postseason defeats are so infamously excruciating, they have names such as the Fumble and the Drive. The Browns have made the playoffs only once this century, despite starting 29 different quarterbacks over the course of 20 years. For three years in the 1990s, the Browns ceased to exist, because their greedy, heartless owner, Art Modell, may he rest in peace, hated it so much in Cleveland that he tried to move the team to Baltimore. Next he fired his head coach, Bill Belichick. The problem with the Browns’ case is Cleveland itself. It’s too grim. The 21st century hasn’t been good to the city, and every unlikely defeat, every clumsy failure, is cut with rust and resignation. If you take pleasure in the Browns’ misfortune, you’re a jerk.

Same goes for all of Minnesota’s terrible teams—the Twins, who have lost a genuinely remarkable 18 straight playoff games; the Timberwolves, who have lost, as far as I can tell, every game they’ve ever played; and the Vikings, who’ve been waiting decades for the chance to lose another Super Bowl. In aggregate, the state of Minnesota’s sports futility might surpass the Mets’, but as stand-alone losers, they’re just too small-time. Ditto for the Cincinnati Bengals, another small-batch loser, whose principal résumé for “best worst” champion is the Ickey Shuffle. In order for the Bengals to be the Mets, Cincinnati would have to be New York. This is yet another case of small-market franchises getting overshadowed and disrespected, to which I can only say boo-hoo. To win at this level of losing, you need a big canvas.

The Los Angeles Clippers—eww. If the Lakers are Hollywood, the Clippers under Donald Sterling were Van Nuys. Their fan base had no discernible identity. They had no discernible fan base. I’ve still never met a Clippers fan over the age of 35. And anyway, that incarnation of the team is gone now. The NBA forced Sterling to sell the team, Steve Ballmer bought it with his Microsoft money, and now the Clippers are the Lakers and somehow still the Clippers.

Which brings us to an important point of clarification regarding New York: The Knicks are not one of the worst franchises in sports. Theirs is an iconic franchise that has been held captive and waterboarded for decades by the worst owner in sports. Being bad isn’t in the franchise’s blood. These aren’t the Knicks. These are the zombie Knicks. And for tristate reasons that will bore you if you live outside the New York–New Jersey–Connecticut metro area, Mets fans also tend to be Jets fans, so take it from a Jets fan when I assure you that the Jets, despite their near-spotless record of blundering incompetence, do not compare to the Mets.

The Jets are the Mets sapped of charm—bright orange and blue turned carsick green. They have the loneliest kind of championship history: one Super Bowl ring, so long ago that it’s become a self-own for Jets fans to bring up. And in all that time, the Jets’ only accomplishment—the only time that the sporting world gazed upon the Jets with genuine wonder—was the Butt Fumble of 2012, the sublime pas de deux featuring Mark Sanchez’s face smacking into teammate Brandon Moore’s derriere on national TV, on Thanksgiving Day, against the fucking Patriots, with such blunt force that Sanchez dropped the ball. It was a play so Jetsy, it was downright Metsy. The whole next decade, though, was a dull-green smear. The franchise’s most electric player was a cornerback, and almost all of his electricity happened off camera. Darrelle Revis spent a decade with the Jets, and in all those years, I saw him on TV maybe seven times. No one ever threw the ball within a mile of him. He was so far off camera that he was invisible.

The point is, we can debate this forever, but the competition is over. We know who the best loser is. The Mets won.

In that infamous inaugural season of 1962, the Mets endured losing streaks of nine, 11, 13, and 17 games, and they capped off the season—loss number 120—by hitting into a rally-killing triple play. To honor the team MVP, Richie Ashburn, the only regular to bat .300 that season, the Mets front office gave him a houseboat, and according to him, it immediately sank.

In 1977, the Mets ran their best player in franchise history out of town in the dead of night, in what instantly became known as the Midnight Massacre. Then, six years later, after the franchise had changed leadership and he consented to a triumphant return, they did it to him again, only this time they ran him out of town by accident. Just this century alone, they wasted a home-run-robbing feat of epic athletic wonder—the best defensive play in playoff history—when their best hitter struck out on three straight pitches in the bottom of the ninth of Game 7 of the 2006 National League Championship Series, with the tying run on second base. Thirteen years later, the Mets hired that guy, the curveball watcher, to manage the team, and weeks later it turned out he was among the masterminds of baseball’s biggest cheating scandal since the 1919 Black Sox.

And then there are the injuries. My god, the injuries. And the illnesses, and the accidents. Mishaps that boggle the mind. It started right at the start: Gil Hodges got kidney stones at the honorary dinner after Old-Timers’ Day at the Polo Grounds in 1962, which is maybe not so shocking for an Old-Timers’ Day, except that Hodges was the Mets’ opening-day first baseman. In 1973, a year that ended with the Mets’ second World Series appearance in five seasons, four Mets were stretchered off the field in the span of a single month. In the fall of 1988, the Mets’ ace left-hander Bob Ojeda chopped off the top of his (left) middle finger with a pair of hedge clippers. Catcher Mackey Sasser, the franchise’s heir apparent to the aging World Series hero Gary Carter, discovered a brand-new strain of the yips, and within five seasons he was out of baseball. In late July 2006, a taxicab containing the Mets’ electric young reliever Duaner Sánchez was struck by a drunk driver, and Sánchez separated his throwing shoulder in the accident—only his throwing shoulder; he had no other serious injuries—and his velocity never recovered.

Chronically bad franchises tend to have far more of their identity bound up in their title droughts than they realize. Once the Chicago Cubs won the World Series in 2016, their first title since 1908, they became what they’ve always been: the luxury-class franchise on the upscale side of a world-class city. The White Sox are the true Mets of Chicago, which is why there’s nothing lovable about the Cubs when they’re not losing.

The Mets will never have this problem. We will never shed our skin. We are the phoenix that rises from the ashes, only to light ourselves on fire and go right back to ashes again. No matter how good things get, we will always revert to our Metsy ways. Winning can’t cure this. In fact, the occasional bout of success is a key symptom of the pathology. This is a terminal condition, and we are blessed to be cursed with it forever.

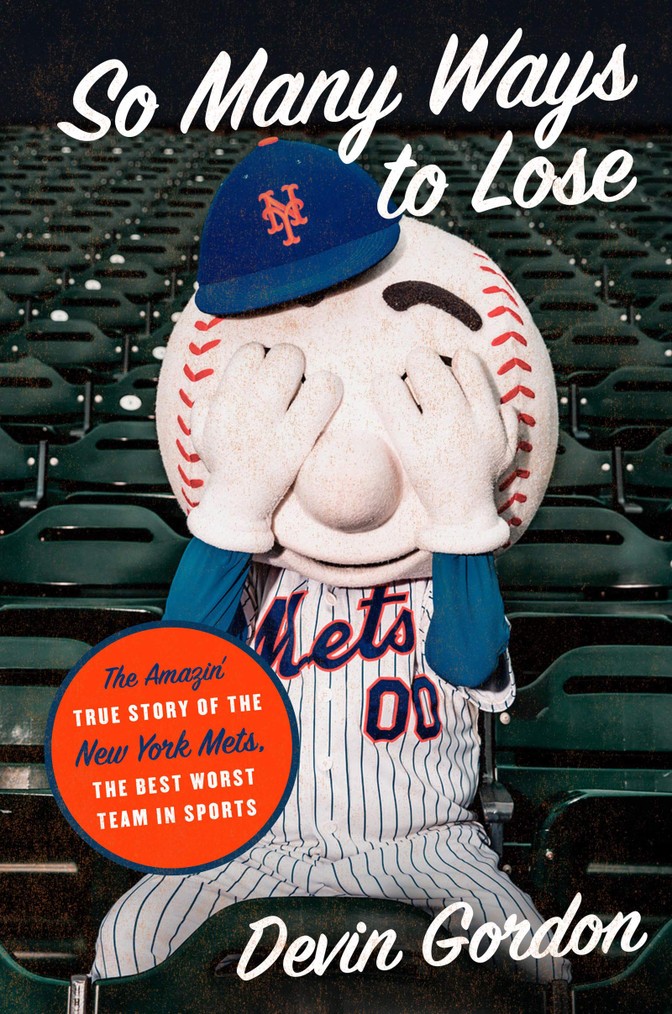

This piece is adapted from Gordon’s book, So Many Ways to Lose: The Amazin’ True Story of the New York Mets—The Best Worst Team in Sports