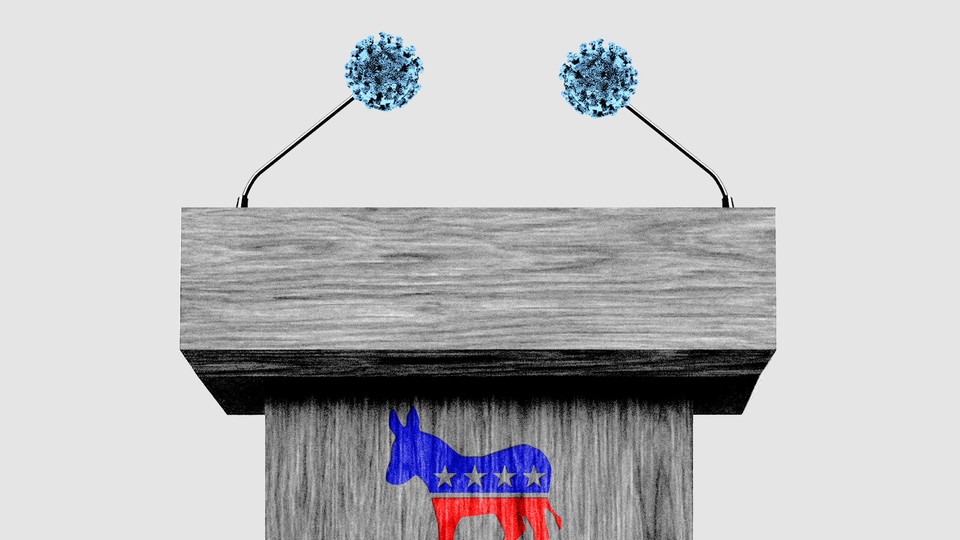

The Coronavirus Killed the Policy Primary

The coronavirus has forced the Democrats to change how they talk about policy.

What a rollout it was going to be. Joe Biden would stand next to former Representative Gabby Giffords at a big rally in Miami the Monday before the Florida primary. They’d rail against gun violence, criticize Bernie Sanders, and get a head start on taking it to Donald Trump in November. It was just what the gun-control movement needed: a big splashy event that would be all over local, state, and national news.

The rally, originally scheduled for March 16, never happened.

Instead, Giffords endorsed Biden in a video on Twitter. The thousands of retweets were nice. But they weren’t what the gun-control movement had been hoping for. Did you know the endorsement happened? If you did, did you care?

Guns. Climate change. Immigration reform. Financial reform. Education reform. Criminal-justice reform. Spending proposals. Tax proposals. The Democratic presidential race was the thickest any race had ever been on policy. Every candidate had an advisory team; every advisory team had white papers and bullet points and ideas of what could, theoretically, happen once its candidate was in the White House and Congress was ready to play along.

Thanks to the coronavirus, that’s all gone. Aside from health-care reform, the pandemic has almost completely overtaken the presidential campaign—and the health-care arguments are mired in the same dug-in pleas for and against Medicare for All that they were over the past year. The coronavirus crisis has rewritten the rules about the scope of the bills Congress can pass, sucked up trillions of dollars in government money, driven the economy into a recession and possibly a global depression, and made clear that its aftermath will define the next four years, no matter who wins in November.

Advocates and activists for the issues Democrats were most concerned about before the virus had been expecting to be out in full force this spring. Instead, they’re sitting at home like everyone else, and they don’t know when their chance will come again, this year or beyond.

“We need to understand that nobody has a crystal ball right now. There are not a lot of people who have a lot of confidence about the way things are going to shape up,” says Peter Ambler, the executive director of Giffords’s gun-safety organization. Squinting for a silver lining in the crisis, he told me that so many people staying at home has meant a drop-off in mass shootings, although the panic-buying of guns has spiked at the same time. It’s also meant that shelter in place is no longer a term used only during shootings. Maybe all the focus on public health will get people thinking differently about gun safety, perhaps the clearest example of American politics’ failure to produce policy that aligns with public opinion.

“At a time when [Americans’] health and safety is at greater risk,” Ambler said, “I do think that gun safety’s going to continue to break through as a kitchen-table issue.”

Just as social distancing was taking off three weeks ago, NARAL Pro-Choice America, EMILY’s List, Planned Parenthood, and several other progressive groups announced a “women’s summit” scheduled for the Sunday before the Democratic National Convention in Milwaukee in July. Now the convention has been moved back to August, and it’s not clear what form it will take. Bringing people together for an additional gathering the day before? Even the leaders of the groups organizing the summit know that’s going to be tough.

“We’re adapting and being even more flexible in our activities, but it’s not an option to throw in the towel on organizing, even—or especially—through this crisis,” says NARAL’s president, Ilyse Hogue. “The GOP always wins when fewer people participate, and beating Trump in November remains a top priority for millions of Americans.”

Everyone being confined to their home almost certainly means that women in abusive relationships haven’t been able to leave. Nonemergency medical procedures being put off almost certainly means that women who might have sought an abortion can’t do so. (Ohio, Texas, Kentucky, and Mississippi have classified abortion as a nonessential procedure, temporarily banning it entirely.) The economic wreckage that the coronavirus leaves behind will almost certainly land disproportionately on women.

That, Hogue told me, means that groups like hers are looking ahead. NARAL is among the groups that have seen an uptick in online engagement, with so many people sitting on their couch with their computer. “Continuing to plan events that centralize women is an act of hope and also a pragmatic way to remind folks just what’s at stake. The energy, ideas, and work that goes into planning will be used to foster solutions if we end up having to cancel an in-person event,” Hogue said.

Meanwhile, remember the family-separation policy? The migrants who were left in detention centers? They were at the center of the Democratic primary race for about a week in June, when all the candidates took a drive from the site of the first debate, in Miami, to look over a wall at the Homestead detention center. They haven’t gotten much media attention since then, even as advocates worry about the spread of the virus in cramped facilities that don’t prioritize showers, let alone hand-washing. The response to and aftermath of the pandemic don’t leave much room for immigration reform. “We know it’s a big battle for us not to be forgotten, so we’ve got to be louder and bolder,” says Javier Valdes, the co–executive director of Make the Road New York, a large immigrants’ rights advocacy organization. Like others, he is reaching hard for optimism, arguing that maybe the crisis will make advocacy easier. “The one thing that this moment also highlights is the intersectionality of all our issues,” Valdes told me.

At 6 a.m. the morning before we spoke, six Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents knocked on the door of a member of Valdes’s group, a Mexican national, in full protective gear and arrested him. Even for that, there won’t be protests. There won’t be press conferences. “Right now, the only thing we can do is call and email,” Valdes said. His fear is that this, too, won’t attract notice.

Then there’s climate change, the issue that had become definitional in the Democratic race, vying with health care in polls about voters’ top concerns. The pandemic might seem like the best imaginable shock to the system to get people serious about climate change—the population of the entire world responding together to a threat measured by science and (hopefully) eventually defeated by science, for better or worse.

But just ask Washington Governor Jay Inslee, the official most identified with fighting climate change, how much time he’s had to talk about the environment while nursing homes and hospitals are being overrun by COVID-19. “It’s worth noting that the people who told us that the coronavirus is a hoax, or not to be concerned with it, are the same people who have ignored the clear and present science on climate change,” Inslee’s former climate-policy adviser, Sam Ricketts, told me last week.

Ricketts is now a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, and though he’s been working on potential policy responses to the pandemic—he stressed that investing in climate-change technology would be one patch for the hole being opened up in the economy—he’s not expecting the coronavirus to create a sudden push for environmental policy. From Barack Obama to Pete Buttigieg, a number of Democratic leaders have suggested that the pandemic might spark that kind of action. But Ricketts isn’t sure.

“I don’t know how much people are going to draw a straight line from a virus that’s killing people around the world, to climate change,” he said.

For others, though, the pandemic makes what once seemed unlikely look more possible. Take the Green New Deal, which Republicans and Democrats alike spent the past two years dismissing as unrealistic and unaffordable. Stephen O’Hanlon, the national field director for the youth-run Sunrise Movement, which has led the charge for the Green New Deal, points out that the plan was designed to take the country out of a recession by making a 1930s-style government investment in fighting climate change. Now that recession appears to be here.

“What we’re seeing is that the next few months have the potential to be a once-in-a-century moment of political realignment in this country,” O’Hanlon told me on Wednesday afternoon. “The Trump administration is talking about bailing out oil and gas companies at the same time that working families are struggling and seeing their paychecks disappear…. It’s a real moment of reckoning for our country.”