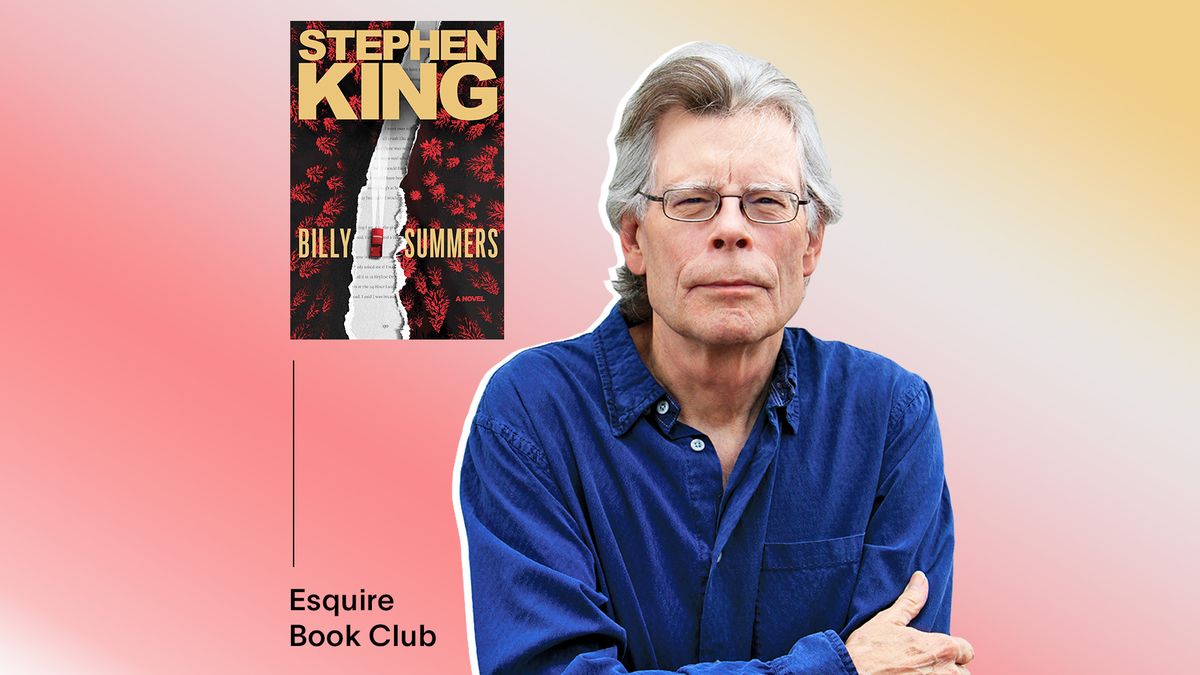

“Did you know that you could sit in front of a screen or a pad of paper and change the world?” asks a character in Stephen King’s Billy Summers, having just written her first work of fiction. She could easily be describing King himself, the legendary storyteller responsible for over sixty global bestsellers, who has changed the world seismically from behind a screen.

King’s latest endeavor begins with a familiar premise: ex-Marine sniper Billy Summers, a principled hit man on the eve of retirement, agrees to do one last job. With an astronomical $2 million payout looming, Billy goes undercover to assassinate a criminal, but the cover his employers dream up hits a nerve: while masquerading as a novelist renting space in an office building, avid reader Billy sets to the task of writing his own lightly fictionalized autobiography, unspooling the wounds of a traumatic childhood and a bruising tour of duty in the Iraq War. It's no spoiler to say that when Billy carries out the hit, things go south in spectacularly bad fashion, sending him on the lam. Billy's escape from the wreckage of the job is complicated by Alice, a young woman he rescues after her brutal gang rape, who becomes an unlikely partner in his plans to get even. Billy and Alice travel everywhere from Reno to Long Island to King's familiar Sidewinder, Colorado; all the while, Billy interrogates the stories he's internalized about his profession as "a garbageman with a gun," wondering if someone who ends the lives of others, even bad people, can be considered good. Remembering a Tim O'Brien aphorism, that fiction "was a way to the truth," Billy writes his way through the morass of his past and present, making for a poignant story about how fiction can redeem, heal, and empower.

King super fans may be surprised to discover that Billy Summers contains little of the supernatural, but to see the undisputed master of horror shift seamlessly into the realm of noir thrillers is proof that King can still surprise and astound us, all these decades later. King spoke with Esquire from his home in Maine about how his novels are connected, how the pandemic will change fiction, and how Billy Summers took him back to his own beginnings as a writer.

Esquire: Where did this novel begin for you?

Stephen King: For me, novels come in pieces. I just collect pieces in my mind, and little by little, they start to connect. With Billy Summers, the first thing for me was this: I saw a man in a basement apartment, looking out a window, like a periscope, and seeing feet go by on the sidewalk. I played with that for a while. What’s this guy doing there? Why is he there? What does it all mean? After playing with that for awhile, I thought of this same guy in an office building, on the fifth or sixth floor of a building near a courthouse. What’s he doing there? Well, he's going to shoot somebody. He's going to shoot a bad guy.

Those two things started to connect. I thought to myself, "He’s going to shoot this bad guy, and then he's going to hide out in this basement apartment, where all the legs are going by.” Those two things, little by little, spun into the whole story. That doesn’t always happen with me, but with this one, it did, and I got a book out of it. Does that make any sense at all?

ESQ: It makes total sense. I like hearing you describe it as “playing with it.” Too often that gets lost; we forget that writing can be fun and playful.

SK: For me, the real fun was this—I'm thinking of this guy in this office building, and he's going to take the shot. I saw the angle of the shot very clearly. I thought to myself, "Well, how's he going to get out of there?" Before I started the book, that was really the place where I was stuck—but I was still having fun thinking about it. Little by little, I got an idea of how he might escape. Then I thought to myself, "Well, you've got to have some kind of story around these two images." That’s when I started to think about, "What if this guy is going to shoot a really bad guy and he's being played?" Then I thought of the famous last job. There are so many movies and books about the last job, which always goes wrong. I said to myself, "Why don't you play into that and write this story as a hard-boiled noir?” That’s the sort of thing I liked to read when I was younger—books by Jim Thompson and Elmore Leonard. And off I went.

ESQ: You write, "If noir is a genre, then one last job is a sub-genre." Why are one last job stories such a cultural touchstone, and how did you seek to reimagine that trope?

SK: Everybody roots for the guy to get out of it. One of the great ones is The Asphalt Jungle, with Sterling Hayden. There’s another one with Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw called The Getaway. There are always jobs that go wrong, but you always hope that the guy at the center of it, who has a good heart, will get out of the job. I think all of us like to play with the idea of what we would do in that circumstance. We all like to take our imaginations for a little walk and pretend for a while that we're on the dark side of the law. Billy Summers really isn’t much different from some of my supernatural books, in the sense that you want the reader to go someplace they don't go in their ordinary life.

ESQ: Novelists talk a lot about finding a character’s voice, but in Billy Summers, you’ve set yourself an interesting challenge: finding not just a voice for the third-person story, but the voice Billy crafts in the pages of his own story. How did you find Billy’s written voice, and determine what he should sound like, telling the story of his own life?

SK: I wanted him to sound like a child when he was a child. He does have this persona of "the dumb self," and he's pretty aware that when he writes this thing on a laptop that’s been given to him by his employer, he's probably being eavesdropped on. That adds to the challenge of trying to write something that will sound like the persona he shows to these people, which is the dumb self—the guy who reads Archie comic books and would never read a novel by Émile Zola or Charles Dickens.

Billy is a lot smarter than the guys that he's working for, which is a lot of fun. But for me, the challenge was trying to write like a person who didn't have any particular talent, or the sort of intelligence we usually associate with writers. I thought to myself, "Can I do this?" Then I thought about As I Lay Dying, where Benjy Compson starts off by saying, "He was in the tall grass, and they were hitting." Little by little, you realize that what he's talking about is a golf game. There’s also Flowers for Algernon, where the guy is dumb at first and then gets smart. That’s sort of like what Billy writes, because he's able to write a little more like an adult, as he grows into his teens. After the job goes south and he's hiding, he feels this tremendous sense of relief, which I felt, too. I said to myself, "Now I can write like a person who’s as bright as Billy really is."

ESQ: You mention Zola and Dickens. It's so fun to glimpse all the writers Billy admires and is drawn to. How did you calibrate what his taste in reading material would be like?

SK: When we first meet Billy, he's thinking about Thérèse Raquin, which is one of Émile Zola's early novels—kind of a scary book. I thought to myself, "Well, this guy's probably read just about everything, but he keeps it to himself." So he mentions various writers. He mentions Tim O'Brien, Émile Zola, Charles Dickens. I assume from that, the reader will say, "He’s probably really well-read. He's read Hemingway and he's read Faulkner, because he talks about As I Lay Dying.” He’s a well-read guy, but he just keeps it under the rose, so to speak.

ESQ: In the scenes where Billy is writing his autobiography, you really put us right there in the game-time decisions of writing. Should he include a certain scene? Should he change a name? Should he explain the function of the M151 rifle? What was it like to inhabit the mind of someone doing this all for the first time, when you've been doing this for over sixty novels?

SK: It was fun. It took me back to the beginning, and to the sense of freedom I felt when I discovered that I could actually drive the story. That's an intoxicating feeling—the sense that you can actually tell a story, and that you can reveal a little bit about yourself. The part of yourself you want to reveal in that particular story, at least. So I loved that part of it very much.

I also wanted to give Billy that sense of freedom. What he writes about are the things he's held in his mind and in his heart, and they’re very important parts of what he became, which is a hitman. Of course, Billy's not stupid at all. In fact, he's really smart. Little by little as he writes his story, his defense mechanisms start to crumble. He realizes that it's kind of a shuck-and-jive to say, "I only kill bad people." He gets to a point where he realizes that he's a bad person himself. In fact, he says that to Alice near the end of the book. He says, "If you stay with me and if you live this life, you'll be ruined." He gains that self-awareness. I don't know if that happens in real life, but it happens in the best novels. The ones that I like, anyway.

ESQ: Have you gained self-awareness while writing a novel?

SK: Yes. I think you find out about yourself a little bit with every book you write, at least the ones that really matter to you. You discover what you believe, and those things come out in the books. But that's really for readers to decide for themselves, I think.

ESQ: In Billy's book, he writes extensively about the Battle of Fallujah. What about that battle and that moment in time was so interesting to you?

SK: The thing is, Billy is a great shooter. A lot of it is just practical considerations. He's a great shooter. Where did he learn to shoot? Of course, that ability is innate, because he's able to shoot the man who killed his sister. He's a killer from the beginning, even as a child. The first person that he kills is a bad person. I said to myself, "Where does a person perfect the skills that it would take to make a shot like the one I’m imagining?" Not a long distance for Billy, but a long distance for anybody else.

I thought, "He learns to be a sniper." It’s unfortunate, but I looked around, and I thought, "Here's how old this guy is. This is the present year. Where would he have been in battle?" Unfortunately, there’s always someplace. America has been involved with a lot of wars over the course of my lifetime. Billy is too young for Vietnam, but he was just right for Iraq. I looked at the years, and then I started to research Fallujah, because that was the cruelest fighting, street by street and block by block, that the Army and the Marines did, so that was the one.

ESQ: Speaking of practical considerations, at various points in the story, you wink at the impending pandemic. You write, "Neither of them knows, no one does, that a rogue virus is going to shut down America." You also have a character saying, "Someday, someone's going to blow up a dirty bomb on Fifth Avenue, or a communicable disease will come along that turns everything from Manhattan to Staten Island into a giant Petri dish." Why did you choose to ground the story in this 2019 context pre-pandemic, but with this omniscience of what's to come, glittering through on the edges?

SK: When I started the book, Covid was, let’s say, a gleam in somebody’s eye. It didn't exist. It was early 2019, before Covid really broke out. By the time I was deep into the book, it was everywhere. We were wearing masks in the supermarket, and we were supposed to shelter in place. People were hoping there would be vaccines. I spent some of that time in Florida, near the Sarasota area. I would go by shopping centers and think, "This is like one of those post-apocalyptic movies," where the huge parking lots from the shopping centers were totally empty—maybe a car or two, and that was it. Movie theaters were shut down, restaurants were shut down, and the cruise lines were shut down.

One of the plot devices I had in my story was the upstairs neighbors. Beth Jensen and her husband come into some money, and they go on a cruise. I thought to myself, "Not in 2020, they don't, because the cruise lines are shut down." My solution for that was to move everything back to 2019, instead of 2020. That made it possible. I felt a little bit like a dog, just skipping the pandemic entirely. But I I've actually read a lot of afterwards in books addressing this. The one I remember best is in a new book by Michael Robotham, where he writes, "Covid doesn't exist in this book, because the plot would be impossible if I put it in." Because of the story I was telling and all the movement, I had to move it back.

ESQ: Going forward, do you think the pandemic has to exist in fiction? Is it a question that writers can’t escape?

SK: That's a key question. That’s really the key question. I don't fucking know. After the Berlin Wall came down, communism is this monolithic thing, the Soviet Union—all that collapsed. There were all these critics and pundits who write about books saying, “Without communism, the spy novel won't exist, and John le Carré will be out of a job." Of course, that didn't happen, because there’s plenty of other employment for spies. There was a time, too, when cell phones started to proliferate, and people said, "This is going to present a real problem for writers who write suspense fiction, because somebody will just grab their cell phone and call the cops." Of course, now the big deal in every horror movie, when you know that things are going to get really bad, one of the characters will say, "I don't have any reception."

Now, I have an idea. I'm at the stage we talked about, where you have different pieces that don't seem to connect, and you look for those connections. I'm at that stage with this. If I can bring it off, it will be set in the year of coronavirus. Somebody has to do it! I think you'll start to see more of this in spring 2022. One of the plot devices that’s bound to become popular—and I'm going to use it in this book that I'm thinking of—is that it used to be when you wanted to kill off parents or a husband or a lover, it was usually a car crash or a plane crash. I think now it'll be coronavirus. "What happened to your husband? You're so young!" "Well, he died of coronavirus." It's bound to happen.

ESQ: Something else I found so winning about this novel were the nods to the Overlook Hotel that come late in the novel. It's such a gem-like reward for loyal readers. How much do you see your novels as connected, or as an extended universe?

SK: I knew they were going to go to Sidewinder, the fictional town that exists in The Shining. There’s actually a scene when they stop at Hemingford Home, which is in The Stand and in a couple of other books, as well. I like to use my fictional places, because they're there, and they're handy, and readers understand that they've come up before. But with the Overlook Hotel, it was a conscious nod to longtime readers—a way of saying, "This is not a supernatural book, but I still remember how I got to the dance." It's like a tip-of-the-hat to the genre.

ESQ: In the back half of the novel, the fragile and ultimately fierce bond between Billy and Alice becomes central. What do you feel exists between these two people that draws them together, a middle-aged hitman and a young survivor of rape?

SK: They’re both survivors. Billy survived a really horrible childhood, killing his mother's abusive lover, and then dealing with her as she descends into alcoholism and drug addiction. Finally, he's taken away and put in foster care. He ends up having to go into the Marines. He’s a survivor of abuse and a really terrible home situation, and she's a survivor of rape. They gravitate toward each other. I didn't know it was going to happen.

There’s this pivotal scene in there, where she's been raped. He doesn't know what to do or how to handle it. Finally, he becomes very fatalistic about it and says, "What's going to happen is what's going to happen." He goes out to get the morning after pill for her. He says, "I'm going to go out and do this. If you want to go to the police, you can go to the police, but I saved your life. I picked you out of the gutter. You would have either choked to death or frozen up there. So do what you're going to do." She sticks with him, and he helps her with her panic attacks, and they become close. I hope it's believable. I think it's believable, but I don't really know. Critics will tell me. Readers will tell me, too.

ESQ: At one point, Alice says of her life story, "There isn't much to tell. I've always been a fade-into-the-woodwork person. Being with you is the only interesting thing that's ever happened to me." We see Alice take ownership over her own story, in this beautiful and surprising way. What did you love about her journey?

SK: Here’s is a young woman that we meet at the very bottom of her life's experiences. This is the worst thing that's ever happened to her. It's one of the worst things that can happen to anyone. She finds a place to go. I think a lot of it has to do with that basement apartment. It's a kind of womb-like place. It's a place to heal, and they heal together. Little by little, they become close. Billy is the one who's able to help her stand on her own two feet.

ESQ: Many of Billy's musings about writing are very powerful and insightful, but one in particular stuck out to me. You write, "He thinks of The Things They Carried, truly one of the best books about war ever written, maybe the best. He thinks writing is also a kind of war, one you fight with yourself. The story is what you carry, and every time you add to it, it gets heavier. All over the world, there are half-finished books—memoirs, poetry, novels, surefire plans for getting thin or getting rich—in desk drawers, because the work got too heavy for the people trying to carry it, and they put it down." Have there been times in your life when the work got too heavy for you, and you put it down?

SK: Ever? Always. It always gets heavy. The longer the book, the heavier it gets at some point. You always have doubts. It's a little bit like sailing in a little boat across a broad ocean. There are big waves, and you're always in danger of being swamped, particularly if you work like I do. I don't have an outline. I just depend on the story to keep on rolling ahead of me. I've had times when the boat sank. I’ve got a couple of unfinished books in my drawers that I just didn't know how to go on with. But the one book that I finished when I got to that point was The Stand. I got to a place where I had too many characters, and the forward motion of the book seemed to have stopped. I felt like I was in danger of sinking into a swamp, and I didn't know what to do. I went for a lot of long walks.

Usually, I work on a book every day. It's like a religion to me. I got to a point in The Stand where I just put it aside, and I said, "I don't think I can finish this." It killed me, because I had like 450 single-spaced pages. You don't want to think of all that work just going to waste—a busted book. I went on a lot of long walks, and I remembered something that Raymond Chandler said. He said, "When you don't know what to do next, bring on the man with the gun." I thought, "Well, what if somebody blows all these people up, and I'm left with a bunch of characters that's manageable?" So that's what I did. I got through that one, but yeah, it gets heavy.

ESQ: Another of Billy's insights that I really loved about writing was this one, when he describes the cabin where his best work happens: "He has done amazing work there, almost 100 pages, creepy picture and all. ‘Maybe a chilly story needs a chilly writing room,' he thinks. It's as good an explanation as any, since the whole process is a mystery to him anyway." Does the process still hold mystery to you, all these novels later?

SK: It's a total mystery. When you ask me questions, like "Where did it begin?," I'm telling you what I remember as honestly as I can, but it's like a dream. I don't really remember very much about where the ideas came from. In the process of writing a book like Billy Summers, I can't remember the day-to-day. It’s like when you wake up from a very vivid dream. Six or seven hours later, you say, "I know I had a dream, but I can't remember what it was about."

But I can remember my dreams, in the sense that when they're fresh, I'm able to write them down. I have the hard copy, and I can look at it. As far as the process that I went through, I can read certain passages over and say, "That was a really good day," or, "That was a hard day, but it doesn't show. Thank God, it doesn't show." Believe me, man. The whole thing is a mystery to me.

I recently read two books that I told The New York Times I would review. One was about Jerry Lee Lewis, and the other was Eric Clapton's autobiography. I said yes in both cases because I'm interested in the idea of talent and how talent shows. Jerry Lee Lewis was a phenomenal piano player, and Eric is an incredible guitarist. I thought, "I'll read these books, and I'll find something out." You know what? I didn't. But I read a great story in the Jerry Lee Lewis book. His relatives, cousins, and aunts were the Swaggarts, in Ferriday, Louisiana. Jimmy Swaggart became an evangelist. They even look alike.

But Jerry Lee told the writer, "We didn't have too much, and they didn't have too much, but they had more than we did. And one day, we walked down these dirt roads to visit them. And they had a piano in the house, and I'd never seen it before. And I didn't know what it was. I just knew I had to get at it." That's the mystery. That's the heart of the mystery. Something inside you calls out and says, "This is for me—this is what I want. I have to get at it."