On March 24, 1945, the 332nd Fighter Group of the U.S. Fifteenth Air Force departed from its base in Italy to escort B-17 heavy bombers on a 1,600-mile round trip flight to the German capital. It was the unit’s longest and most dangerous bomber escort mission of World War II. The target: Daimler-Benz’s tank assembly plant in Berlin, heavily guarded by fighter planes like the lightning-fast Messerschmitt 262s—the world’s first jet fighters, flown by some of the Luftwaffe’s best pilots.

Approximately two dozen Me 262 jets attacked the American bomber formation as it approached the target. The Tuskegee Airmen, flying their red-tailed P-51 Mustangs, fought back against the German jets. While the Me 262s were much faster than the propeller-driven planes, the Mustangs were more maneuverable. The Tuskegee Airmen shot down three enemy aircraft in the skies over Berlin that day, successfully hitting the tank factory and helping clear the path for the Allied Advance into Germany.

Flying bombers on these long-range raids into Nazi-controlled Europe was one of the most dangerous jobs in World War II. The Luftwaffe frequently targeted behemoth bomber planes like the B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator; in many early raids into Nazi territory, more than half the crews never made it home. The only protection the vulnerable bombers had were the fighter escorts that guarded them over enemy territory.

And if you wanted the very best escorts, you wanted the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots in U.S. military history.

Fighting to Exist

Nicknamed the “Red Tails” for the distinctive red-painted tails of their fighter planes, the Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 individual sorties and some 1,500 combat missions in World War II. In nearly 200 escort missions, they lost just 27 bombers, significantly fewer than the average loss of 46. But these pilots weren’t just fighting against fascism overseas—they were also battling racism at home.

And against all odds, they won.

In the late 1930s, the German army was spreading through Europe. Although the U.S. hadn’t yet declared war, thousands of Americans were signing up to fight overseas as pilots. But at the time, racist stereotypes were widespread in the U.S. military. The Armed Forces were segregated, with black servicemen often restricted to working menial labor jobs. Nowhere was this inequality more apparent than in the Army Air Corps, which didn’t just segregate black servicemen from their white counterparts, but outright excluded them.

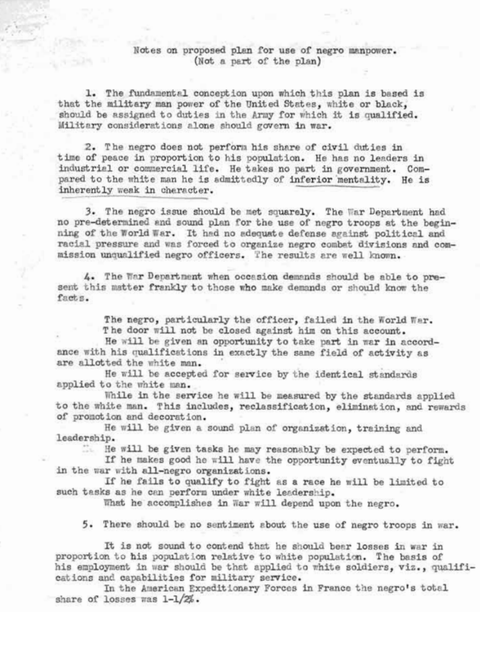

To justify, military leaders pointed to a racist Army War College report released after the First World War. The report claimed black people were an inferior “sub-species” of human who lacked the intelligence and courage to serve in combat, especially in challenging roles like pilots.

For decades, civil rights leaders had been fighting against such prejudice, lobbying for equal treatment in the military. The pressure mounted when the U.S. started preparing for war. In 1938, anticipating the need for more pilots, the Army Air Corps began establishing flight schools at colleges all across the country, excluding black schools. However, advocates’ efforts were about to pay off. In 1940, while campaigning for his third presidential term, Franklin Delano Roosevelt promised to start the first training program for black military pilots.

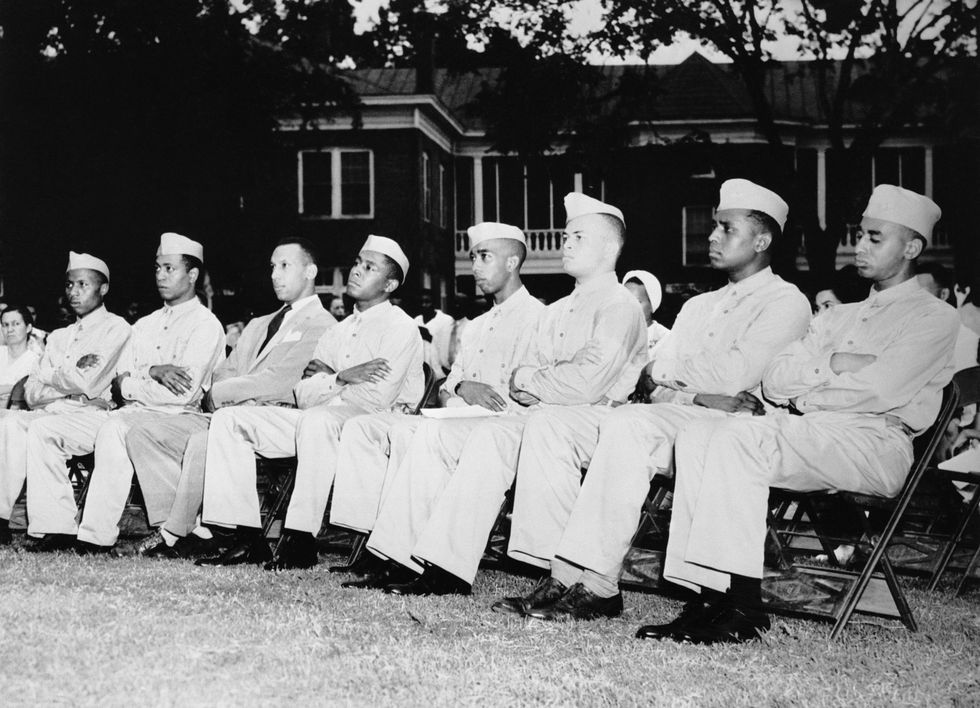

After winning reelection, Roosevelt ordered the War Department to form its first black flying unit: the 99th Pursuit Squadron, later renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron. In July 1941, the first members began cadet training at the Tuskegee Institute in Tuskegee, Alabama. After the attack on Pearl Harbor six months later, the U.S. would go to war.

The "Tuskegee Experiment"

With the U.S. mobilizing for war in the early months of 1941, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Tuskegee Institute, jumped in the back of a biplane, and—reportedly ignoring the advice of her security detail—went for a 40-minute flight over Alabama with Charles Alfred Anderson, a black pilot and chief instructor at the institute.

After the flight, Roosevelt posed for a photo with Anderson, and the image soon filled newspapers around the country, helping publicize an increasingly controversial program.

The Army Air Corps had reluctantly agreed to train black pilots for combat, but insisted on keeping the unit segregated. Dubbed the “Tuskegee Experiment,” the Air Corps designed the program to test whether black pilots had the ability to fly planes as well as white pilots. Many military leaders fully expected the “experiment” to fail, but the pioneering aviators were fiercely determined to prove them wrong.

The first aviation cadets at Tuskegee were a small group of college-educated men from across the country. The 12 students in the first class, many of whom had prior flying experience, included one student officer, Captain Benjamin Davis, Jr., who later took command of the 99th Fighter Squadron and eventually became the first black general in the U.S. Air Force.

Davis was the son of one of the first black officers in the U.S. military, and he himself was the fourth black American to ever graduate from the West Point Military Academy, which he accomplished despite being ostracized and ignored by the white cadets and faculty at the school.

“Living as a prisoner in solitary confinement for four years had not destroyed my personality, nor poisoned my attitude toward other people,” Davis later wrote in his autobiography. “I had even managed to keep a sense of humor about the situation; when my father told me of my many supporters, the many people who were pulling for me, I said, ‘It’s a pity none of them were at West Point.’”

By the end of the war, 992 pilots had earned their wings at the Tuskegee flight school. Another 14,000 support personnel also graduated from the program to serve as navigators, mechanics, radio operators, instructors, medics, and other crucial members of the flying unit. Stationed in the heart of the “Jim Crow” South, the trainees endured shameful discrimination throughout the rigorous program. They were banned from certain areas on the base and in the surrounding towns, where many businesses wouldn’t serve them.

But Davis encouraged his crew to respond to each injustice with exceptional discipline. The Tuskegee Airmen resolved to fight against racism by proving themselves in the cockpit. “We would go through any ordeal that came our way,” Davis wrote, “be it in garrison existence or combat, to prove our worth.”

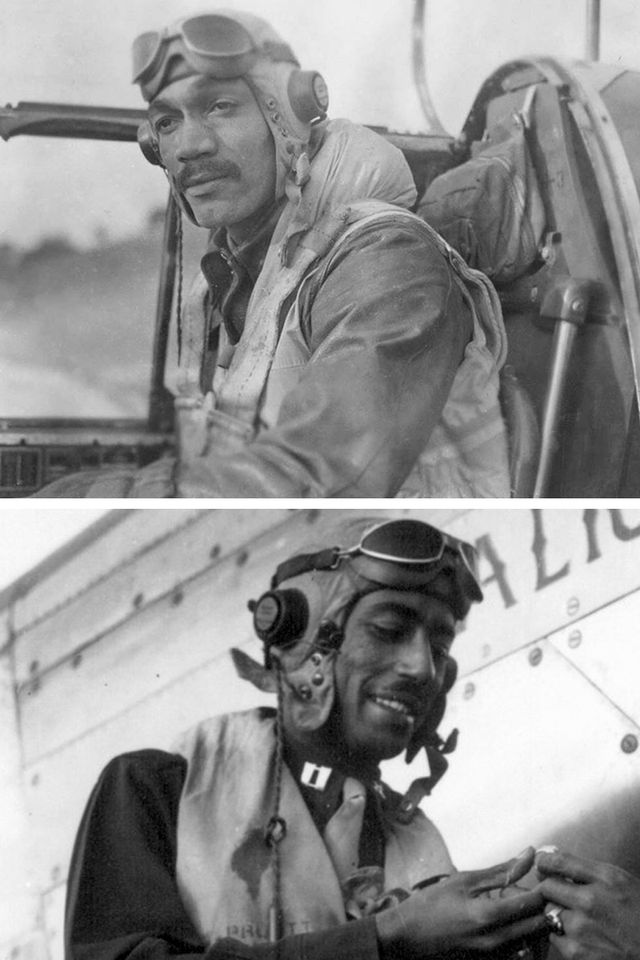

In April 1943, the Army Air Corps sent the 99th Fighter Squadron to war, and Davis led the first black pilots in American history into combat.

Heading to War

During World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen carried an extra burden. They knew an exemplary performance in combat would challenge the racist stereotypes held by many Americans. “We knew we had to have discipline,” former Tuskegee pilot Milton Holmes later told a local newspaper in 2017. “We had to be better than everyone because everyone expected us to fail."

After first arriving in North Africa, the 99th Fighter Squadron headed to the Italian islands of Pantelleria and Sicily, where they provided air cover for Allied ships in the Mediterranean and attacked enemy targets on the ground. But discrimination followed them everywhere they went.

In North Africa, a group of senior officers attempted to have the squadron pulled out of combat duty completely. Davis, at this point a lieutenant colonel, passionately defended his squad to the War Department, which found no fault with the unit’s performance. In fact, the 99th Fighter Squadron soon received a Distinguished Unit Citation for its missions over Sicily, and another for shooting down 13 enemy aircraft while covering the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland during the Battle of Anzio.

The unit continued the fight, but it was once again segregated as the 99th was joined by three other squadrons out of Tuskegee to form the 332nd Fighter Group, an all-black unit within the Fifteenth Air Force. It was also given a new primary mission: to escort heavy bombers over enemy territory, a task that would make the Tuskegee Airmen famous.

The Legendary Red Tails

In July 1944, the Tuskegee Airmen were given new planes: the P-51 Mustangs. For identification, the tail sections of the Mustangs sported a distinctive crimson color. With the color came a new name: the “Red Tails.”

The coveted P-51 Mustang could fly faster and farther than any of the unit’s previous planes. It was originally designed as a dive-bomber for the British Royal Air Force. When it was upgraded for the Air Corps with powerful new Rolls-Royce Merlin engines, it became one of the greatest fighter planes of World War II.

The P-51s were perfect for guarding bombers on long-range missions into Axis-controlled territory. The planes had a range of up to 1,000 miles and could out-maneuver the best Luftwaffe fighters in the air. Tuskegee Airmen made a name for themselves on these escort missions. Over the course of 179 escort missions, enemies only shot down 27 bombers—far fewer than the average fighter escort.

As commander of the 332nd Fighter Group, Colonel Davis set a high bar for excellence. He ordered his pilots to stick close to the bombers they were guarding, rather than peel off to chase down enemy planes. As a result, the Red Tails had no “aces,” or pilots who shot down five enemy planes. But the unit’s main focus wasn’t scoring aerial victories—it was protecting Allied bombers. And the Red Tails did this exceptionally well.

By some reports, bomber crews would specifically request the Tuskegee Airmen as their escorts, and began calling them the “Red-Tailed Angels.” The German Luftwaffe also had a nickname for the Tuskegee pilots in recognition of their skills, calling them the Schwarze Vogelmenschen, or "Black Birdmen."

Targeting enemy oil refineries, factories, and airfields, the 332nd Fighter Group flew all over southern and eastern Europe in the final months of the war against Nazi Germany. Eventually, they flew all the way to Berlin in their longest escort mission of the war, shooting down three German Me 262 jets during the raid and earning a third Distinguished Unit Citation.

On May 7, 1945, a little more than a month after the Berlin raid, the Germans surrendered to the Allies.

The Fight Back Home

By the end of World War II, the Tuskegee Airmen had achieved a record of excellence that left little doubt as to the ability and courage of black aviators in combat. The squad earned more than 850 awards, including 95 Distinguished Flying Crosses, eight Purple Hearts, one Silver Star, and 744 Air Medals. As for the cost, 66 airmen were killed in action, and another 32 were captured as prisoners of war.

With such accolades, the Tuskegee Airmen should have been welcomed home as heroes, but instead they were met with racial prejudice, sometimes as soon as they stepped foot back onto American soil.

“When I came back to the U.S. and down that gangplank, there was a sign at the bottom: ‘Colored Troops to the Right, White Troops to the Left.’” Tuskegee pilot Lt. Col. Lee Archer told the Chicago Tribune in 2004. “At that time I said, well, you know, this is a pity,” he later added.

The fight in Europe may have been over, but the crusade for racial equality in America was just beginning, and the Tuskegee Airmen helped pave the way. They forged an indelible example that inspired President Harry S. Truman to sign an executive order in 1948 banning racial discrimination in the military. With the help of Col. Davis, the newly formed U.S. Air Force was the first of the military branches to desegregate its ranks.

The integration of the military set a precedent for desegregation in America. “The Tuskegee Airmen preceded Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks,” Robert D. Rose, the vice president of Tuskegee Airmen Inc, told the New York Times in 2008. “If they hadn’t helped generate a climate of tolerance by integration of the military, we might not have progressed through the civil rights era. We would have seen a different civil rights movement—if we would have seen one at all.”

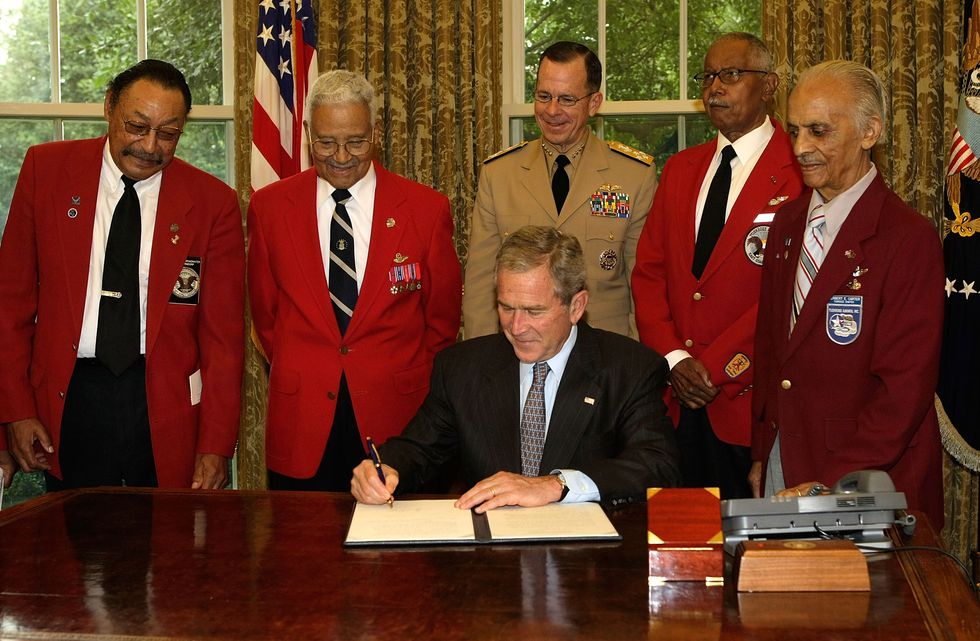

More than half a century after the war, the pioneering airmen—now the subject of two feature films and a permanent exhibit in the Smithsonian—were formally honored for their contribution. In 2007, some 300 of the original airmen—many of whom had gone on to lead extraordinary lives of service as activists, professors, doctors, politicians, and war heroes in Korea and Vietnam—traveled to the U.S. Capitol to receive the Congressional Gold Medal.

Two years later, the surviving airmen, by then in their 80s and 90s, were again invited to Washington—this time to attend the inauguration of Barack Obama, the first black president of the U.S. At the ceremony, Obama told the group, “My career in public service was made possible by the path heroes like the Tuskegee Airmen trail-blazed.”

The determination and courage of the Tuskegee Airmen helped change the country they fought for. As of 2020, nearly 50,000 black pilots and personnel serve in the United States Air Force, making up around 15 percent of America’s flying force.

Meg is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn. She’s had the pleasure of nerding out about history and tech for Atlas Obscura, Motherboard, and Gizmodo.