ORANGEBURG — Lane 1 always gave him problems. The wall to his left prevented him from finding just the right position to ensure the counterclockwise spin he put on the ball would propel it toward the pins with the finesse needed for a strike.

A well-aimed hook was easier to accomplish a lane or two to the right, and that’s where John Stroman liked to be for his league nights — near the concessions, near the front door of All-Star Bowling Lanes.

The last time he bowled here was about 20 years ago. His black 16-pound ball, with his initials J.W.S. etched above the finger holes, sat on the rack when not in use. He’d left it there, even after he stopped going to the venue, even after it closed for good in 2007.

The ball collected dust.

But Stroman’s memories of the bowling alley always have remained stark and immediate. For this was the place where he once led volatile student protests. Here was the place where police landed their batons on his head.

This was the scene in February 1968 when Black students from S.C. State College and Claflin University gathered to vent their frustration over segregation in Orangeburg, where they were met with violence and fear, where they ran the gauntlet.

Here, at the All-Star Bowling Lanes, was where the first events occurred in a confrontation that would culminate two days later in a burst of violence on campus.

Stroman was the student who started it all, and he has no reason to regret what he did.

S.C. State College and Claflin University students march to protest Orangeburg's All-Star Bowling Lanes' refusal to admit African Americans. The protests culminated in highway patrolmen shooting dozens, and killing three young men, at S.C. State on Feb. 8, 1968, an incident now called the Orangeburg Massacre. Cecil Williams/Provided

Abandoned and languishing for 13 years now, the downtown bowling alley on Russell Street is being reclaimed thanks to an anonymous donor’s gift. The donor purchased the property for $145,000 and transferred the deed to the Center for Creative Partnerships, which seeks to apply the arts and humanities to the fight for social justice and civil rights.

The center was started by Ellen Zisholtz in the 1990s. In January of this year she transformed it into a nonprofit, and soon assembled a board of directors, and then a project advisory board. Now it must raise the money for the renovation work.

The goal is to restore the bowling lanes and to create a museum and learning center devoted to the Orangeburg Massacre and the events leading up to that first-ever campus shooting in the U.S. involving law enforcement.

If all goes as planned, the Orangeburg All-Star Justice Center will include several operational bowling lanes, an exhibition space, a venue for public gatherings and discussion, informational displays, interactive features and possibly an outdoor movie screen where documentaries and relevant feature films can be shown, Zisholtz said.

Ellen Zisholtz, director of the Center for Creative Partnerships, is invested in Orangeburg and its history. She worked at S.C. State University for years, and now hopes to transform All-Star Bowling Lanes into a community bowling and history center. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Joining 'The Cause'

Stroman, tall, lean and unsteady on his feet at 77 years old, is back inside the bowling alley, listening, remembering. The ball-carrying equipment is in pieces. Old advertisements are mounted above each lane. The carpet is damp and smells of mold.

Bowling balls, gloves and bags left behind in the empty locker room inside All-Star Bowling Lanes in Orangeburg. In 1968, students from S.C. State College and Claflin University protested owner Harry Floyd's segregation policy. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

The ghosts of the segregated past still hover in the air. All the bustle and change since 1968 — the dropped pins, the noise and camaraderie of league nights — can’t quite drown out the sounds of police sirens and cries of pain.

When he was 15, growing up in Savannah, he worked as a pin boy at a local bowling alley. After his shift in the evenings, he and his friends would hop on their bikes to ride home. Sometimes White teenagers in their cars would follow them, rolling down their windows to shout epithets and taunts, or to toss something at the Black boys pedaling furiously to escape their abusers.

On one occasion, one of the White boys, wielding a belt, leaned too far out the window and fell from the car. Stroman and his friends hardly looked back; they knew they would be blamed for the injuries the White teen sustained. So Stroman quit his job at the bowling alley.

All-Star Bowling Lanes, empty since 2007, could become an active venue again after a restoration project led by the Center for Creative Partnerships. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

In March 1960, when he was 17, he witnessed the start of what would become a 19-month boycott of White-owned businesses downtown. The city’s Black residents, led by the NAACP, challenged segregation first at the retail lunch counters, then throughout Savannah, until, in October 1961, city officials opened the parks, pools, restaurants, retail shops and buses to all.

In 1963, during his first year in Orangeburg, where he had joined one of his brothers and enrolled at S.C. State College, Stroman was among hundreds of students who sought to join a protest march through the downtown commercial district, but police were there to greet them. Several protesters were beaten and around 400 arrested. Stroman and many others spent two weeks in jail.

By the middle of his sophomore year, his grades were suffering. It didn’t help that Stroman was quick to reject school rules he considered unfair. He was gaining a reputation as a troublemaker. He took time off from school and moved to New York City, staying with a brother and converting to Islam, giving up cigarettes, pork and alcohol for the rest of his life.

But he wasn’t one to quit hardship, so he returned to Orangeburg — to his school work, his friends and his protests.

In February 1967, he was one of three students who demonstrated in front of college President Benner C. Turner’s home on campus. The students objected to the dismissal of three capable White professors, to the structure and discipline imposed on the school’s young people, to the dress code and compulsory chapel attendance, and to what was called the Berlin Wall — a tall barbed-wire fence separating Claflin and S.C. State, which had been constructed after the protests of the early '60s.

The unrest soon expanded across the campus and became known as “The Cause.” A young organizer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Cleveland Sellers, traveled to Orangeburg to advise students, advocate for fair policies and more Black studies programming. He also promoted the formation of the Black Awareness Coordinating Committee, which Stroman promptly joined.

The old sign for All-Star Bowling Lanes has disintegrated over the years. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

For his activism, Stroman was expelled from school. But the die had been cast. Gov. Robert McNair negotiated an effective settlement, and pressure was placed on Turner to step down. By the fall of 1967, many of the students’ demands were met, Turner was replaced by a far more sympathetic M. Maceo Nance, and students ejected from the school were re-admitted.

Sellers, by then a Black Power proponent closely associated with the firebrand orator and SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael, was perceived by the conservative White establishment of Orangeburg as a threat — though his focus was cultural and educational. He wanted young Black people to push for change by unshackling their minds, embracing their history and awakening to the interconnectedness of oppressive regimes around the world. His agenda was that of self-determination and self-empowerment.

Stroman, instead, wanted to bowl.

Initial challenge

For years, Black people in Orangeburg sought access to All-Star Bowling Lanes, but its management kept the venue segregated. Black bowlers were forced to drive nearly an hour to Columbia.

In October 1967, Stroman was singularly obsessed with ending segregation at the local bowling alley. Sellers, quickly labeled the “outside agitator” by authorities though he hailed from nearby Denmark and contemplated enrolling at S.C. State, returned to Orangeburg to continue his advocacy work on campus and rally support for BACC. The two men generally did not see eye to eye.

Stroman soon found an opportunity to challenge the new owner of All-Star Bowling Lanes, Harry Floyd. The lanky activist was approached by fellow student James Davis, who had returned from six years in the Air Force only to discover he was still prohibited from patronizing the nearby bowling lanes. Davis wanted to take action.

Bowling pins still stand inside All-Star Bowling Lanes on Oct. 20, 2020, in Orangeburg. In 1968, students from S.C. State College and Claflin University badly wanted to knock them down, but owner Harry Floyd's segregation policy prohibited them from accessing the venue. So students launched a series of protests that culminated in the Orangeburg Massacre. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Stroman, back in Savannah for the holidays, could not get the idea out of his head.

“All I could hear was 'bowling alley, bowling alley, bowling alley,' " he said.

He visited a venue in his hometown and explained the problem to the White owner.

“Do they have a lunch counter?” the owner asked. If so, even a private business could be subject to the interstate commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution, making it illegal for them to segregate by race.

Stroman and Davis devised a scheme, recounted in the book "The Orangeburg Massacre" by Jack Bass and Jack Nelson. They would ask S.C. State’s only White student to be a foil. He would go to the bowling alley on Monday, Jan. 29, followed by a small group of Black patrons who would then challenge the assertion that the venue was a “privately owned club.” If an unknown White student who was not a club member could gain entry, why not the Black students?

Oscar Butler, dean of men at the college, learned of the effort and went to observe. About a dozen young people sat at the lunch counter and were ignored. When they asked for lanes, they were told the bowling alley was a private club. The students pointed to their White friend, who was immediately ordered to stop bowling. Floyd told the group to leave, but they resisted, hoping the owner would call the police. They played music on the jukebox and purchased soft drinks from a vending machine.

Then Floyd insisted that Butler escort the students out.

Harry Floyd, owner of the All-Star Bowling Lanes in Orangeburg over which civil rights demonstrations ended in the death of three students, points to the "privately owned" sign on the front door on Feb. 10, 1968. File/AP

Stroman conveyed the incident to BACC, but the student group was concerned with other matters. He wrote a letter to the American Bowling Congress, reporting the discrimination and asking for intervention. The reply was disappointing. The organization would do nothing.

One week later, on Monday, Feb. 5, league night, about 15 young people showed up at All-Star Bowling Lanes.

“We came to bowl, man!” someone said as he entered the building.

“This is a private business!” came the reply.

“We’re tired of ‘private,’ we’re coming in!”

Every small item touched by an African American was tossed in the garbage, Stroman said. A student wrapped his arms around the juke box. “Throw this away!” came the challenge.

That’s when Floyd called the authorities.

Orangeburg Police Chief Roger Poston showed up and told Floyd he’d need to secure arrest warrants in order to take action. The city ordered the bowling alley closed for the night, and about a dozen protesters were forced to leave.

The confrontation was escalating, and on the next night it devolved into violence and bloodshed.

'A lot of hate'

The law was muddy. Was Floyd exempted from the requirements of the Civil Rights Act because of his business’ private status, or did Black protesters have a right to patronize the venue? The city decided to side with Floyd.

When Stroman returned Tuesday evening with another group of students, they were met by around 20 police officers, including members of the state Highway Patrol deployed by Chief J.P. (Pete) Strom of the State Law Enforcement Division. Strom told the young student leader that trespassers would be arrested, but it would only take one or two arrests to trigger a court case that challenged Floyd’s policy.

Highway patrolmen and city police gather at All-Star Bowling Lanes in Orangeburg on Tuesday, February 6, 1968. File/AP

Word spread to keep cool and disperse, especially after about 15 students were handcuffed.

That might have been the end of it, but someone rushed to campus and told students watching a movie about the arrests at the bowling alley. Enraged, hundreds made their way to the venue, where the situation soon spiraled out of control.

A small group burst into the venue but were forced out after about 25 minutes. A renewed effort to disperse the crowd in an orderly fashion nearly took hold, then fell apart when a firetruck pulled into the parking lot. Students were quickly reminded of a 1960 confrontation during which students were repelled with firehoses.

“Where’s the fire?” they taunted, waving cigarette lighters.

All-Star Bowling Lanes, renamed All-Star Triangle Bowl before it was closed in 2007, could become a working bowling alley again if the Center for Creative Partnerships succeeds in its renovation project. The venue will also feature a museum and information about the Orangeburg Massacre. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Stroman stood atop a car and urged the students to leave. Another 50 officers arrived. First they moved near the firetruck to protect it as it pulled away, but students surged in the direction of the venue, so officers rushed after them. Windows shattered. A student was arrested. Another sprayed something caustic into the eyes of an officer. Pushing and shoving quickly led to the swinging of batons.

Students, many of them young women, were injured. Stroman was struck on the head. On their way back to campus, some shattered shop windows with bricks.

"That’s what galvanized the student body," said Bill Hine, a retired history professor who taught at S.C. State. "If things had dissipated that night, maybe nothing much would have happened."

The next day was tense. McNair called in the National Guard. FBI agents maneuvered quietly through the city, keeping an eye on Sellers. State troopers established a center of operations just outside the main entrance of S.C. State College. The city was on lockdown, its White residents warned of impending riots.

Two young White men sped onto campus in their car, firing gunshots from the windows, then driving into a dead-end. They spun around and sped away. Two Black students felt the sting of birdshot as they took a common shortcut to campus through a private yard.

Negotiations in the city failed to diffuse the tension. Frustrated students were confined to campus.

Thursday night — Feb. 8, 1968 — a large group of unarmed students gathered on a bluff near the edge of the campus, lit a bonfire and confronted an army of local police, state troopers, National Guardsmen and military vehicles. Patrolmen under Strom’s command lined up at the curb, guns loaded with buckshot aimed at the college students.

An officer’s gun went off. A wooden bannister was thrown by a student, striking one of the officers in the face. And then, a little after 10:30 p.m., the buckshot hissed across the bluff and found the flesh of angry protestors. Many were struck in the back or the soles of their feet as they scrambled to escape the 8- to 10-second barrage.

South Carolina state troopers on the campus of S.C. State College in February 1968. File/AP

Henry Smith was shot in the neck and shoulder. Delano Middleton was shot in the chest. Samuel Hammond was shot in the back. They died that night. At least 28 others were wounded.

Sellers had been struck near the armpit. At the hospital later, he was arrested on several charges, including inciting a riot. Stroman, though, was not there. He had gone to stay with his aunt on the west side of Orangeburg. He tried to get back onto the campus around 6 p.m. the day of the shooting, but was turned away.

He learned of the carnage at 7 the next morning, while listening to the radio.

“I wanted to kill everything in sight,” he said. “I had a lot of hate in me.”

'A big hole'

Stroman finished school, got certified in math, science and chemistry, married in 1970 and tried to find a job as a school teacher in Orangeburg. But no one would hire him, he said. Over the years, he would find work in Allendale, Denmark, Elloree and elsewhere.

Soon after the Orangeburg Massacre, Floyd opened his bowling alley to all, and Stroman was its first Black patron. He joined the league and appeared routinely, using his heavy engraved ball and avoiding Lane 1.

At the venue last week, he listened to Zisholtz describe the renovation plans. The dropped ceiling would go. The carpet would get ripped out. Big TV screens would be mounted over each working lane providing information about the civil rights movement. An interactive feature would display messages typed by visitors promising their commitment to social justice. A museum display would describe the historical significance of the bowling alley.

“It’s really going to serve as an educational flagship,” observed Anna Zacherl, who sits on the board of the Center for Creative Partnerships and who runs the Orangeburg County libraries.

Jermaine Middleton, niece of Delano Middleton, stands by the doorway to the Orangeburg bowling alley on Oct. 20, 2020. Her uncle was one of three killed while demonstrating on the campus of S.C. State College on Feb. 8, 1968. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Jermaine Middleton, an advisory board member and niece of Delano Middleton, one of the three students killed in 1968, said the project is a way to remember her uncle for generations.

“I don’t know who my cousins would have been,” she said, musing about the generational disruption the killing caused. “What was it like for my grandmother, who lost her youngest son? ... I think about it a lot. ... There’s a big hole in our family.”

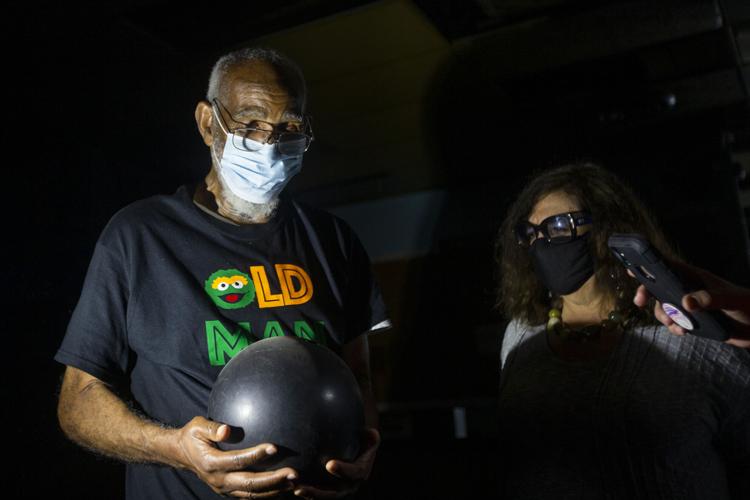

John Stroman revisits the All-Star Bowling Lanes on Oct. 20, 2020. This was the scene of violent student protests in February 1968. Stroman played a central role in challenging segregation at the Orangeburg bowling alley. Gavin McIntyre/Staff

Stroman is mostly silent, listening, thinking. He mentions he left his ball here two decades ago, just before the venue, which had been renamed All-Star Triangle Bowling, closed for good.

Zacherl turns on the flashlight of her mobile phone and examines the balls remaining on the racks. Suddenly, the initials J.W.S. are illuminated.

Stroman tests the finger holes to see if they fit.

And then he carries his ball away.

Photos: Segregated bowling alley will be transformed to commemorate Orangeburg Massacre

All-Star Bowling Lanes closed in 2007. The scene of student protests in February 1968, the venue is to be renovated by a local nonprofit to commemorate the Orangeburg Massacre and the demonstrations leading up to it.