Editor's note: This story is available as a result of a content partnership with the Financial Times. Subscribers will see stories like this every day on our website (and in our daily emails) as an added value to your subscription.

Ten days before the end of 2018, WeWork’s new $60m Gulfstream took off from a small airport north of New York and set a course for Kauai, Hawaii’s garden island. On board was Adam Neumann, the company’s messianic co-founder, who had a plan to hit the waves with surfing legend Laird Hamilton — and a $20bn secret.

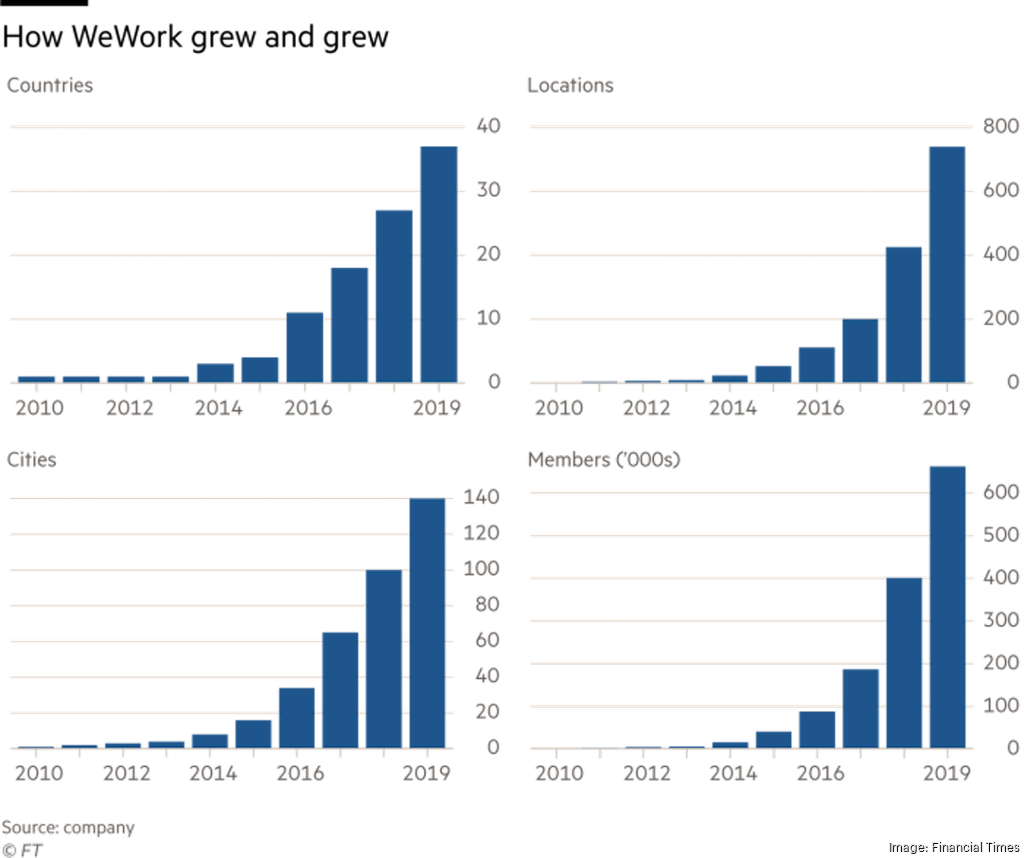

It was less than a decade since the 6ft 5in Israeli had sketched out a plan with his friend Miguel McKelvey for turning dull offices into empowering communities for restless entrepreneurs. But WeWork had already overtaken JPMorgan Chase as New York’s largest commercial tenant and controlled more square feet in London than anyone but the UK government.

Their pitch went beyond simply offering short leases to start-ups in need of flexibility. WeWork, with its pinball tables, meditation rooms and beer on tap, would not only look different: it would offer a physical social network to a generation of millennials wondering whether there was more to life than their screens.

Neumann’s vision of creating a new work culture — and more — was suddenly everywhere. “We are here in order to change the world,” he once said. “Nothing less than that interests me.” And he had a good time in the process, marking milestones with raucous tequila parties and celebrating with his growing group of employees at hedonistic summer-camp festivals.

At 39, Neumann was already worth billions. This was thanks in part to one man: SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son, a Korean-Japanese electronics prodigy who had made and lost a fortune in the dotcom era, and then built another from bets on the likes of Alibaba and Uber, the stars of a new tech boom.

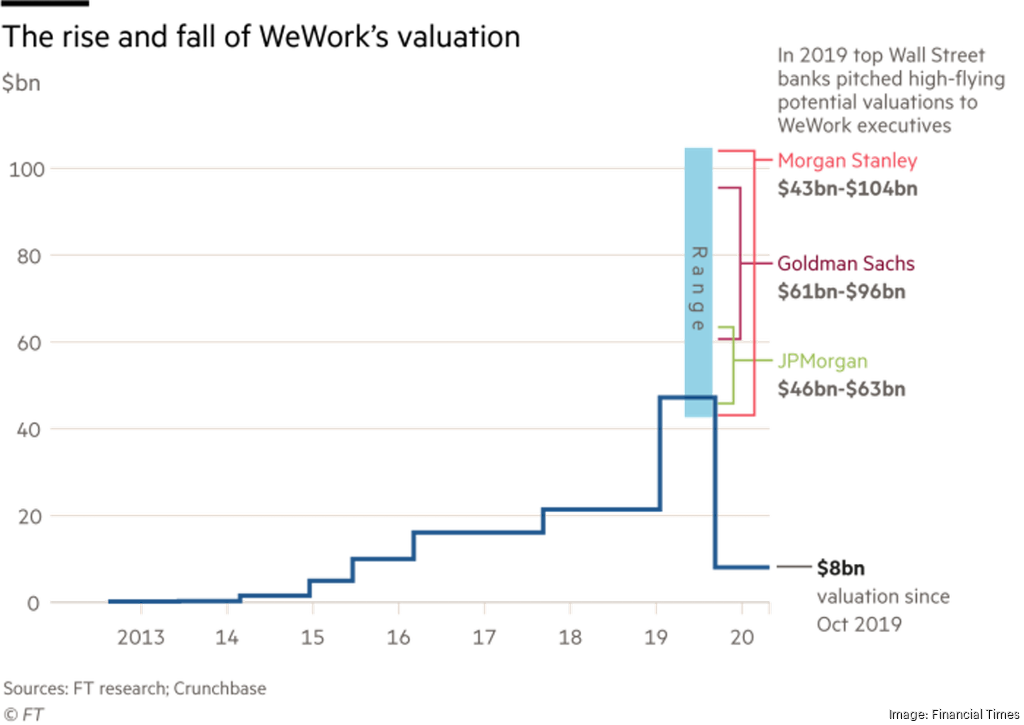

Neumann liked to boast that it took just 28 minutes for Son to decide to buy into WeWork. In 2017, SoftBank and its $100bn Vision Fund invested $4.4bn at a $20bn valuation — one of the largest investments in a private company in history. In 2018, SoftBank committed another $4.25bn, making WeWork one of the world’s leading “unicorns”: start-ups that had achieved price tags in the billions of dollars without going public — and often, like WeWork, without making a profit either.

But what Neumann knew as he flew to Hawaii was that documents had gone to the printers to seal a deal the likes of which no other entrepreneur had pulled off. The plan, codenamed Project Fortitude, would see Son increase his latest investment to $10bn, and buy out almost every investor but Neumann for another $10bn. It would secure Neumann’s grip on a company he hoped to keep in his family’s control for generations, backed by an investor with enough capital to fund a vision that grew more ambitious the more time they spent together.

Yet within a year the Gulfstream would be up for sale, Neumann would be out of a job and WeWork would come within two weeks of running out of money. SoftBank would be forced to bail it out and slash the value of its earlier investments.

This stark reversal in WeWork’s fortunes would embarrass Wall Street veterans who had fought for the chance to lend to it. It would also fundamentally change how markets view other start-ups without the profits to sustain their ambitions.

WeWork had surfed a unique economic moment: the financial crisis had left swaths of prime office space empty and laid-off workers were starting afresh as “gig economy” freelancers. With interest rates at historic lows, private markets boomed as investors chasing higher returns competed to fund a new generation of founders. But in their search for the next Amazon, these financiers valued disruptive but loss-making companies in ways that stock market investors barely recognised.

No one had more power to set prices in this unicorn economy than Son. “We identify the entrepreneurs who have the greatest vision to solve the unsolvable…And then we provide the cash to fight,” he said last October.

As Jeffrey Rayport of Harvard Business School observes, the “brute force” of capital can let a start-up scale so fast that no rival can catch it. But if its spending outruns the money coming in, that can create “its own variety of brute force”.

If a unique market moment propelled WeWork’s rise, what dragged it back down were forces that have reasserted themselves throughout business history: hubris, greed and the gravitational pull of cold, hard cash. The bubble in which start-ups from Beijing to Berlin were floating depended on money continuing to pour in, even as some burnt through it at stunning speed. This account, based on interviews with dozens of current and former employees and advisers to WeWork and SoftBank, is the story of what happened when the cashflow stopped. What really deflated the most pumped-up unicorn of all?

In hindsight, Neumann’s lieutenants now say, Project Fortitude was the turning point for both WeWork and the easy-money era it represented.

WeWork’s model was simple: leasing space from landlords, renovating offices and then finding new tenants. A desk at one of its locations in New York’s financial district costs $560 a month. Some risks were clear from early on: its SoHo loft aesthetic didn’t come cheap, its leases far outlasted the monthly memberships that most of its early tenants signed, and the business had never been tested with a serious recession. '

But investors kept coming, and it was Neumann who brought them in; nobody at WeWork was better at prying cheques from investors such as Benchmark Capital and Fidelity. Despite earlier failed start-ups selling women’s shoes with collapsible heels and baby clothes with kneepads, he had a way of convincing sceptics. Lloyd Blankfein, the former Goldman Sachs CEO, previously told the FT he was “a great salesman”.

Raised on a kibbutz in Israel, Neumann had moved to the US for college. His parent’s divorce made his childhood “tumultuous in ways I’m not going to get into”, his wife Rebekah told the FT last year. She too had lived an eclectic life: trading equities after studying business and Buddhism, performing Chekhov at the Old Vic and training as a Jivamukti yoga teacher.

Neumann was known for exhorting his team to “hustle harder” and tackled negotiations for Fortitude with his customary confidence. If he owed much of his fortune to Son, he did not show it, persuading the older man to give him voting control even as SoftBank prepared to take a majority stake. Son also agreed to a $47bn valuation at which members of his own team had baulked. This would make WeWork the world’s most valuable private start-up after Uber and lift Neumann’s wealth — on paper, at least — to $13bn.

Exhausted advisers hammered out other extraordinary terms. Neumann was known for his hard-partying habits, including smoking marijuana on the jet. “He was paying attention for about an hour, but then he went into another compartment and when he came back he was baked,” one person who had accompanied him on a business trip recalled.

Son and Ron Fisher, the SoftBank vice-chairman who led the negotiation, had concluded that Neumann’s taste for tequila and marijuana was not a deal-breaker, but they wanted a mechanism to take control if things went badly wrong. Lawyers agreed that SoftBank could oust Neumann as chief executive only if he committed a violent crime and was jailed in a common law jurisdiction.

Drug use would not be enough to trigger the clause and, even if he were jailed, Neumann could regain control on his release. It was an extreme example of the trust funders placed in founders at a time when venture capitalists liked to boast how “founder-friendly” they were.

But Neumann wanted further reassurance that he would not wake up one day to find SoftBank had thrown billions at a competitor. When Son asked for a pledge that he would not launch a competing office-space provider, Neumann dispatched Jen Berrent, one of his top deputies, to demand that SoftBank agree in return not to finance any direct rival. The demand was anathema to Son, who often bet on several companies in a single industry.

Some of Son’s executives were also arguing against his WeWork investment, echoing outsiders’ warnings that the company was a property business merely masquerading as a tech group. Real-estate veterans doubted its business model: past attempts to take on the risk of subletting long-term leases to tenants who could walk away had ended in tears. In 2018, the FT crunched the numbers and concluded that WeWork was worth closer to $3bn than the $20bn valuation of the time.

For weeks, negotiations continued in Tokyo, Boston and New York. Neumann sometimes showed up barefoot, or encouraged his team to hold hands and pray. But when he got down to business he was “super sharp”, advisers recall. In at least one negotiation, he mentioned his friendship with Jared Kushner, Donald Trump’s son-in-law.

To SoftBank, which was in the midst of a regulatory fight over the sale of its US wireless provider Sprint to T-Mobile and had grown used to Neumann driving a hard bargain, it sounded like a veiled threat, though Neumann’s people insist there was no such intention. Son’s team doubted that Neumann had any sway at the White House, but couldn’t be sure. “He wanted everyone to know he was God,” one of them said.

As the finishing touches were made to Project Fortitude, plans to reveal the investment were underway. Neumann wanted to announce it at an employee gathering featuring a performance by the Red Hot Chili Peppers. When he told colleagues that he would simultaneously announce a new company mission — to elevate the world’s consciousness — he was met with stunned silence, one recalls.

What WeWork executives — and Neumann — failed to realise was how much Son had chafed at the founder’s demands. The idea of his protégé handcuffing him from investing in other real-estate groups was too much, people briefed on his thinking said. As the tech-propelled stock market rally wobbled and SoftBank’s shares suffered over concerns that it was overexposed to WeWork, Son changed his mind. On December 24, he called Neumann in Hawaii to tell him that the deal was off.

It was the first fracture in a relationship Neumann had rhapsodised about. “For Adam, who had massive trust issues, to have this person who was like a father figure to him do this to him, I can’t emphasise how devastating that was,” one of his top deputies said. “I don’t think he ever really recovered. Almost all of his crazy actions from there to stepping down were tied to that.”

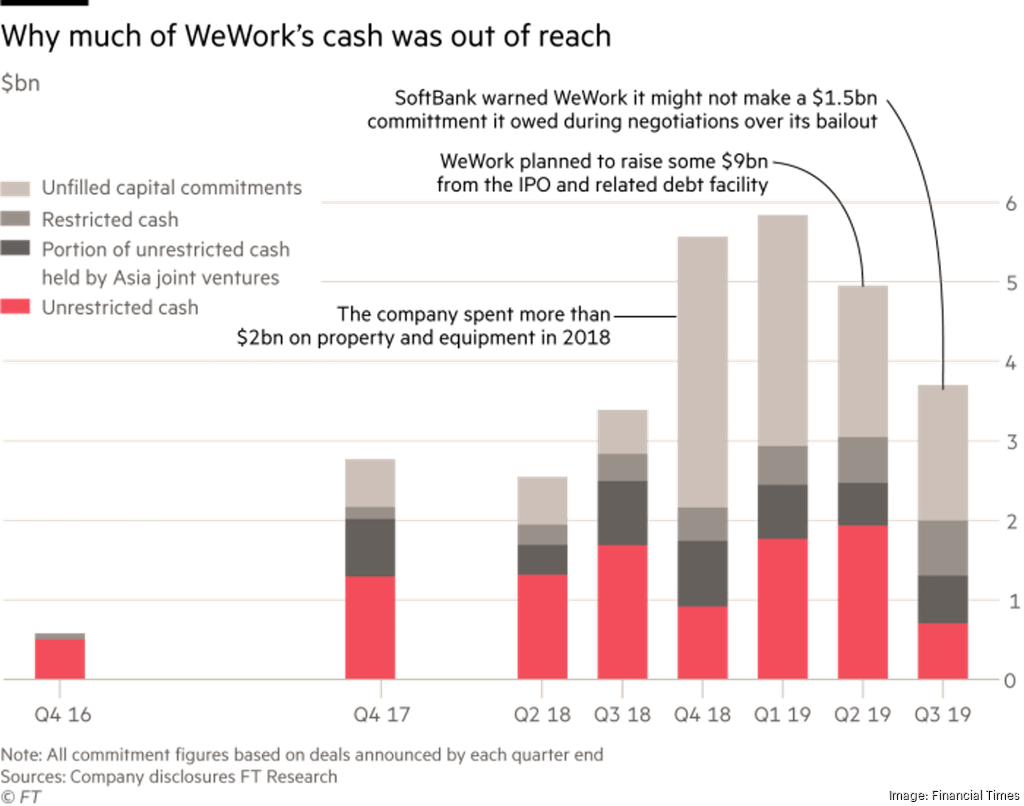

For WeWork, the countdown to catastrophe had started. Neumann took his jet to Maui, the nearby Hawaiian island where Son was staying, and convinced him to commit another $1bn of new capital. But unless he found more money, his free-spending company would soon run out of cash.

Back in the US in January, Neumann put a brave face on things. “Our balance sheet has north of $6bn on it. It’s above and beyond what we need to fund the company for the next four to five years,” he told a TV interviewer, nursing a finger he’d broken while surfing. Beside him, Ashton Kutcher, the actor who had invested in several start-ups but not WeWork, said it was “insane” to suggest the sum his friend had raised was disappointing, adding that he found SoftBank’s $47bn valuation “extraordinarily reasonable”.

But this inflated price would come to haunt both Son and Neumann. WeWork had banked $6.7bn of investments and SoftBank had now promised another $4.4bn in stages, yet it ended 2018 with less than $1.75bn of cash. That year alone it had spent more than $2bn on property and equipment, converting buildings from Poland to the Philippines to its familiar aesthetic. The orders for $9,400 pairs of Børge Mogensen-designed chairs were adding up.

Insiders had almost forgotten about the cash burn rate, assuming that billions of dollars more funding would soon arrive. From the start, Son had egged Neumann on to expand more ambitiously, whatever the cost. “He came in and said, ‘Woah, woah, woah; wait. Why only [aim for] a million members when you can have five?’” Neumann told the FT last May: “Every single number we had, he said, ‘It’s too small.’”

Son’s strategy was a classic land grab, driven by the theory that start-ups needed to plant flags as quickly as possible to establish global dominance before anyone else could copy their idea. Unicorn investors were only interested in big ideas: hypergrowth was the only acceptable mode.

During the Fortitude negotiations, Son had dangled a carrot to focus Neumann on more outlandish growth. If WeWork’s annual revenues shot from $2bn to $50bn in five years, its management’s share of the company could rise from 37 per cent to 51 per cent. Although this target died with the buyout plan, the culture of breakneck growth remained.

Colleagues suspected that Son exploited the fact that Neumann saw him as a father figure. One executive recalled a conversation in which Son referenced Oyo, the hotel chain SoftBank had backed. “Your little brother…is really performing faster [and] better than you guys,” he recalled Son telling Neumann. “Let me take you through their deck and how well they’re doing.”

“Masa was poking the bear,” the executive said. “Adam would say, ‘We’re not going fast enough; we’re not being bold enough.’” Keen to claw back a majority stake, Neumann told his team to start working towards the new target before Project Fortitude even closed. “Because Masa was pushing the company so hard in that time we were burning more money than we otherwise expected to spend,” said the executive.

Knowing WeWork’s need for cash, Berrent and chief financial officer Artie Minson had prepared a plan B. Days after Fortitude fell apart, they filed the paperwork to prepare for a stock market listing that they thought could raise billions. But neither Neumann nor Son relished the idea of going public. Neumann had already had a taste of the grilling investors might give him after the company tapped debt markets in 2018. As a public company, WeWork could expect even more scrutiny.

Instead, he stayed in his $21.4m house north of San Francisco, complete with guitar-shaped living room and water slide. One of a reported six homes he owned, it was a good base from which to hunt for cash-rich tech investors. He had lunch with Luca Maestri, CFO of Apple, and pitched to Google and Salesforce, whose founder Marc Benioff said last year that Neumann was “probably one of the greatest entrepreneurs I’ve ever met”. But no one invested.

In New York, Minson and Berrent tried another tack: turning to the bankers who had been wooing WeWork for years. Wall Street’s biggest names began vying to lead the IPO, with Morgan Stanley dangling a potential valuation as high as $104bn. But Neumann was still looking for alternatives. That spring, WeWork started talks with Goldman Sachs over a loan of up to $10bn — more than enough capital to avoid a listing.

Meanwhile, WeWork was spending as if it already had the money. It burned through $2.4bn in the first six months of 2019, opening more properties and snapping up more start-ups. Neumann had raised internal growth targets the previous year, but the real-estate team was struggling to keep up.

He pressed them harder in May 2019, determined to keep growth above 100 per cent for a ninth consecutive year, a WeWork executive recalls. In 2018, WeWork had added 252,000 desks. The new plan: 750,000 in 2020.

“There was enormous pressure,” one current employee said. “People were having nervous breakdowns trying to sign new space. We were always aggressive, but we became ridiculously aggressive.” Staff began spending tens of thousands of dollars to fly furniture around the world because they could not meet their deadlines by shipping it.

Around Independence Day weekend in July 2019, Neumann got a call which shook his funding expectations. Stephen Scherr, Goldman’s CFO, rang to say that the bank was not ready to commit to the full $10bn financing it had pitched.

Neumann raced to the banker he had long turned to for advice: JPMorgan’s chief executive, Jamie Dimon. The silver-haired New Yorker had taken a keen interest in WeWork, seeing the chance to lead its IPO as both lucrative and critical to the bank’s rivalry with Goldman and Morgan Stanley. He agreed to let his team step in, but wanted reassurance that Neumann would not jump back to Goldman, and that JPMorgan would get the bragging rights as lead underwriter. Neumann agreed.

By August, Dimon’s team had cobbled together $6bn in loans with other banks, but it made the financing contingent on the IPO raising at least $3bn in new equity. Without it, WeWork wouldn’t get a penny.

That summer, Neumann was still voicing his reluctance to go public. Minson would tell him that he had no choice, two former colleagues recalled, although some say the CFO continued to paint a bullish picture of finances in staff meetings. Others suspect Neumann discounted any warnings. As one financial adviser says, “How do you go from succeeding by not listening to succeeding by listening?” Besides, one WeWork executive adds: “There was never a thought that we couldn’t get [the IPO] done.”

Companies wanting to list on US exchanges must file a detailed S-1 document with the Securities and Exchange Commission. WeWork, which had already raised investor eyebrows with novel and flattering measures of profitability such as “community-adjusted ebitda”, had been haggling for months over what the SEC would accept.

As an IPO loomed closer, a complex restructuring passed potentially lucrative tax benefits to Neumann, Minson and Berrent and gave the CEO’s stock 20 times the voting rights of other shareholders to ensure his control. JPMorgan bankers warned some WeWork executives that this governance structure could hit its valuation hard, perhaps by 30 per cent. A former senior colleague claims this message never reached Neumann.

Neumann, who usually slept only four hours a night, often directed operations from afar. Flight logs show WeWork’s jet took him to the Dominican Republic (twice), the Maldives and Costa Rica between March and May. He returned to Costa Rica in August but spent much of the time leading up to the publication of the S-1 in the Hamptons, with a stream of advisers commuting from New York.

The filing, which was made public on August 14, left governance experts aghast. The Neumanns would retain control even in the event of Adam’s death, with Rebekah — who had been elevated to co-founder and described as her husband’s “strategic thought partner” — holding the right to pick his successor.

Worse, the document revealed how WeWork had paid Neumann rent in buildings he owned, bought the trademark to the word “We” from him for $5.9m and let him sell stock — hundreds of millions of dollars worth, reporters established.

Investors found the financial picture just as concerning, laying bare the company’s spending and offering little hope that it would start producing real profits. Sidelines such as WeGrow — the $42,000-a-year-in-fees kindergarten Rebekah ran from WeWork’s Chelsea headquarters — looked like costly vanity projects. If insiders had not been focused on WeWork’s fast-draining cash reserves, outsiders now were.

Investors made clear that they were not interested in anything near a $47bn valuation. “It just went from bad to worse with investors,” said one senior source. By September, advisers concluded that the market would only stomach a price of $15bn-$18bn. WeWork canvassed investors to gauge interest before launching a roadshow but Neumann won few of them over.

Executives cheered when Zoom, a video-conferencing provider, agreed to invest $25m but advisers were alarmed: to raise the $3bn on which JPMorgan’s debt deal depended, they would need orders worth $6bn-$9bn.

Neumann hoped to complete the IPO before the Jewish high holidays, and time was running short. He repeatedly put off recording his portion of the roadshow video and appeared anxious to some colleagues. Even on the eve of the roadshow, WeWork did not have its story straight. And although Neumann brought out tequila shots when filming wrapped, a sour chaser soon followed.

In mid-September, The Wall Street Journal published details of his in-flight marijuana consumption. Investors had heard about WeWork’s party culture but this was the last straw. Without serious governance changes, Neumann’s bankers told him, the IPO was dead. That was not just a blow to his pride: WeWork had only $2bn of cash left, and would run out of money in less than two months without the listing.

Neumann went to Dimon’s offices on Sunday September 22, telling colleagues beforehand that he might have to step down as CEO. Both his Wall Street mentor and Bruce Dunlevie, the Benchmark Capital partner and WeWork director who had been one of its earliest investors, agreed. Stepping back to be chairman, Neumann saw, was the best hope of protecting what he had built.

WeWork elevated Minson and Sebastian Gunningham, a vice-chairman, to co-CEOs. As they set about identifying thousands of lay-offs, the pair briefed top managers on Neumann’s exit. Berrent launched into a full-throated defence of him, leaving employees on the video call speechless. Within a week, WeWork had aborted its IPO and advisers concluded it needed $5bn quickly.

JPMorgan scrambled to put together a rescue, but discovered to its dismay that the money on which its plan depended — a warrant under which SoftBank was due to inject $1.5bn in April 2020 — was not set in stone. SoftBank said it could pull the funding if WeWork went with JPMorgan’s proposal, and stepped in with its own offer — $5.05bn of new debt, $3bn to buy out investors and employees, and $1.5bn in new cash.

Son’s rescue came with further demands as well: that Neumann give up his chairmanship and hand his voting rights to the board. To sweeten the pill, the Japanese group offered him credit with which to repay a $500m bank facility on which he was in technical default, agreed a $185m “consulting fee”, and said he could sell up to $970m of his shares to SoftBank. With just two weeks’ cash left, Neumann and WeWork accepted Son’s bailout. Its $8bn valuation was just over a sixth of the $47bn valuation Son and Neumann had agreed 10 months earlier.

Two decades after losing $70bn in the dotcom crash, Son has had to write down SoftBank’s investment in WeWork by $4.6bn and rein in his hopes of raising another $108bn for the Vision Fund. But he effectively controls WeWork, where he has installed a loyalist as chairman and a property veteran as CEO.

Even after the rescue, WeWork still has little room for error. The company has some $50bn of lease obligations it has promised to fulfil and has acknowledged that the spectacular failure of its IPO plans could scare off new customers. The defining unicorn of the era of private capital has warned that it may never secure an IPO.

Colleagues and advisers who once bought into Neumann’s vision of higher things than office politics are now pointing fingers at each other. Some ex-employees sound disoriented as they tour other workplaces. “I am deeply, deeply in love with WeWork. I love what it used to be,” one former vice-president says. “Looking at other companies, they all look either too small or too slow.”

But without its co-founder, WeWork is a very different company. “Adam was the sun and we all revolved around him,” one employee reflects. “We were kings of the world.”

WeWork, with new, more cautious, plans of generating cash by 2022, is still expanding: it expects its membership to swell by another 50 per cent in the next three years. Its valuation may have become untethered from reality, but its advocates say that it nonetheless reset how we think about our workspaces and changed a property market measured in the trillions of dollars.

Entrepreneurs always need to create what Steve Jobs called a “reality distortion field”, argues HBS’s Rayport, “because they’re pitching something that doesn’t exist yet.” Some, such as Elizabeth Holmes of Theranos, the blood-testing start-up that collapsed in scandal, never manage to bend reality to match their vision. But ever since John Pierpont Morgan funded Thomas Edison in 1878, investors have shown a willingness to suspend their disbelief. “The difference between Elizabeth Holmes and Thomas Edison is the light bulb,” says Rayport.

The world still has an estimated 450 unicorns, but after WeWork’s implosion the modern-day Morgans are more wary. As another SoftBank-backed CEO, Uber’s Dara Khosrowshahi, put it in an earnings announcement earlier this month: “The era of growth at all costs is over.”

As for Neumann, he is now sitting in Tel Aviv and debating whether to sell his shares to SoftBank or stay fully invested in the vision he sold to the world. The Neumanns’ lofty mission for WeWork remains unfulfilled, but Rebekah is said to be keen to move the family back to New York for a second act. While he waits, other hustling entrepreneurs are pitching him their own start-ups.

Eric Platt is the FT’s US mergers and acquisitions correspondent. Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson is the FT’s US business editor. Additional reporting by Arash Massoudi in London