Analysis: tactile paving allows vulnerable and mobility-impaired people to read the streets and navigate with comfort and confidence

We walk them every day. Babies often bounce and squeal as their buggies are pushed over them. Some of us even complain about tripping over them. We don't think much about them, but they make a huge difference to the quality of life for many people - and we need lots more of them.

I’m referring to the tactile paving installed to help visually impaired or blind people safely navigate our urban roads and streets. Tactile paving refers to paving units that bear distinctive, raised surface profiles to be detected by both sighted and visually impaired pedestrians. It's part of a movement towards universal design, a philosophy that strives to create the best quality of life for everyone, regardless of their abilities.

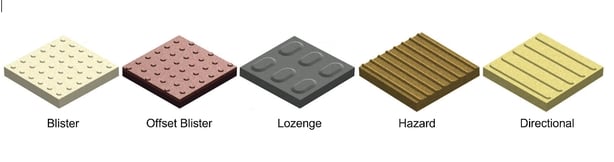

Different surface profiles are intended to denote different hazards. There are two predominant types of tiles: those with raised dots indicate caution and those with long, parallel strips provide directional cues. Tactile paving blocks are used at pedestrian crossings, bus stops, shared cycle paths and railway platforms.

The blister surface is designed to warn visually impaired people who might otherwise find it difficult to differentiate between where the footpath ends and the roadway or carriageway begins. This is increasingly important as we try to make footpaths flush with roadways to enable wheelchair users to cross unimpeded. Early examples had rounded blisters around 6mm high but the blisters, or truncated domes or cones, are now designed to be 4 to 5mm high since early examples were deemed to be uncomfortable.

Many visually impaired people lose their sight due to diabetes, a condition which can also reduce sensitivity in feet and hands so finding the optimum height is a fine balance. Colour-coding blocks can give additional information for partially-sighted users about whether the crossing is controlled or uncontrolled by traffic lights in which case the surfaces should be red or buff respectively.

Offset blister surfaces warn visually impaired people of a large hole or chasm ahead and are widely used at train platforms. Lozenge shape surfaces warn that they are approaching the edge of an on-street bus or Luas platform. Buff colour is recommended but it can be any colour (other than red) which contrasts with the surrounding surface.

Hazard surfaces, often called guiding, or corduroy patterns, convey the message 'hazard, proceed with caution'. Consisting of a series of rounded bars running across the direction of pedestrian travel, it warns of the presence of specific hazards like steps, level crossings, where a footway/footpath joins a shared route or the approach to on-street light rapid transit platforms.

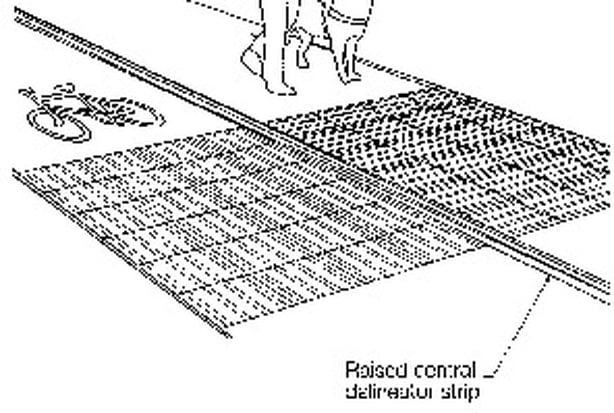

Directional or guidance surface paving is used to indicate the safest direction of travel for the visually impaired. The raised flat bars have rounded ends. "Cycleway" tactile paving is used to advise visually impaired people of the correct side to enter a segregated shared cycleway track/footway where it is not possible to physically separate the pedestrian and cyclist sides by, for example, a difference in level. A "ladder" pattern is created on the footpath side perpendicular to the direction of travel and a "tramline" pattern in the direction of travel on the cycle track with a central delineator strip with a white finish between the two.

Seiichi Miyake, the Japanese inventor who developed this system in the 1960s, was trying to help a friend who was losing their sight. Inspired by braille, Miyake hoped the visually impaired would be able to "read" the pavement with their feet or a cane and called his creation "tenji" blocks after the Japanese word for braille. As the blocks were rolled out across Japan they were initially far from uniform, which caused confusion for users, but an international standard now exists.

The official international standard calls for the use of red blister surfaces, but this has often been ignored for aesthetic or other reasons. Some early installations in Ireland may not be fully compliant with this standard, particularly in terms of the colour contrast requirements and some appear quite dirty. This presents a challenge for the visually impaired since colour can be as important as tactile sense for people who have impaired vision.

Tactile pavements are incredibly useful and help the visually impaired to navigate hazards in their area. A disadvantage is that they really only help visually impaired people navigate in settings they already know. Voice guidance delivered using navigation apps can work in parallel to tactile paving to help the visually impaired navigate their way. Additional research is needed to make the tactile paving more durable and reduce the frequency at which it needs to be replaced due to wear and tear.

Dublin's transport infrastructure is being transformed through various initiatives such as Bus Connects and the increased installation of integrated bike pathways. As we try to roll out more sustainable modes of transport, we must consider the real needs of vulnerable and mobility-impaired people when designing every aspect of the infrastructure. Mobility-impaired people in this context includes those who are visually impaired or blind, hard of hearing or deaf, having children in buggies in addition to wheelchair users and people with crutches.

By taking their needs into account, we can ensure they can move around their built environment with comfort and confidence. This will mean rolling out more and more tactile paving and more uniformity in terms of how it is manufactured, installed and maintained for us all.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ