After hedging its bets late last November by pumping $318 million of dollars to sustain rival engine upgrade programs for the F-35A Lighting stealth jet, on Monday, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall informed the media that the service finally made its call by closing its Adaptive Engine Transition Program, for which $4 billion has already been spent.

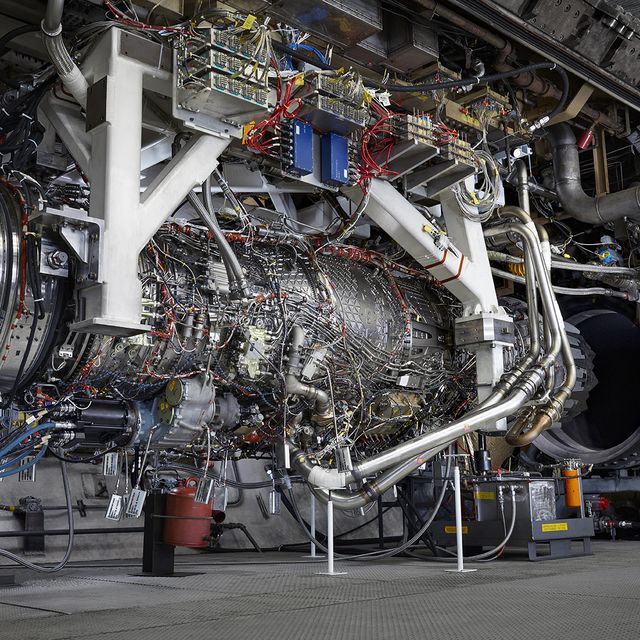

That marks a setback for General Electric, which offered a revolutionary new engine made of advanced composite materials that could re-optimize mid-flight between fuel-efficiency and performance for the widely exported stealth jet. And it’s a victory for a lower-risk Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) of the jet’s current F135-100 turbofan engine proposed by manufacturer Pratt & Whitney at less than half the development cost.

That upgrade will be lumped into the F-35’s broader (and much-delayed and over-budget) Block 4 upgrade program, which has otherwise been billed as being primarily a software patch that will enable use of many new weapons, sensors, and avionic systems. However, electrical demands and thermal loads imposed by additional systems necessitated changes to the F-35’s engine to improve heat management.

Modern turbofan engines must always strike a design compromise; they can achieve high fuel efficiency by allowing more air to bypass the engine core, or they can achieve peak thrust and performance by limiting bypassing air. Unsurprisingly, supersonic jet fighters tend to have low-bypass turbofans, though that comes at cost to their range and endurance.

Adaptive cycle (or combined cycle) engines developed for the AETP program allow the best of both worlds, as well as improved cooling, by directing a third stream of air to either increase or decrease the bypass ratio depending on the desired performance regime. General Electric estimated its XA100 engine would increase the F-35’s range on internal fuel by 30 to 35 percent and thrust by 10 to 20 percent, redressing Achilles heels of the F-35.

Adaptive cycles engines are likely the future of advanced jet fighter propulsion—but the question remained whether that future could be retrofitted into the F-35 at acceptable cost and risk.

The decision today shows the Air Force concluded it could not. “We were not able to fund the AETP,” Kendall told reporters. “We needed something that was affordable, and that would support all the variants.”

Suggestively, Pratt & Whitney had developed its own XA101 adaptive cycle engine, but argued it wasn’t worth fitting on the F-35, and claims it couldn’t be done for the F-35B. Pratt’s incremental upgrade, estimated to cost $2.7 billion, would boost range by 7 percent and thrust by 10 percent.

In an email disputing Pop Mech’s prior coverage of the engine competition, a General Electric spokesperson argued the engine was “drop-in ready for 90 [percent] of the planned procurement of F-35s” and would offer “billions in savings over the full life cycle of the engines,” while deriding the Pratt & Whitney’s upgrade as a ‘band aid solution’, which would require further costly tweaks later on. GE also saw a “path” to adapting the adaptive cycle technology to the F-35B, which has a different F135-600 engine with lift fans for vertical-takeoff capability.

Perhaps the Air Force was feeling risk-averse as the F-35’s jet’s protracted developments stood as an example of how costs and delays can unexpectedly multiply when new technologies prove more difficult to integrate than anticipated. Moreover, lack of institutional interest—and thus funding—of AETP from the Marine Corps or Navy (which operate F-35Bs and Cs) meant the Air Force didn’t want to take on GE’s estimated $6 billion development cost alone.

The work funded by the AETP isn’t being thrown away, as it will undoubtedly inform the Air Force’s Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) program seeking to prepare adaptive cycle engines for Air Force’s forthcoming NGAD sixth-generation fighter—an aircraft that apparently already has a flying prototype, and represents the future of the service’s air superiority mission.

Sébastien Roblin has written on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including 19FortyFive, The National Interest, MSNBC, Forbes.com, Inside Unmanned Systems and War is Boring. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.