DULUTH — Tom Rusch, the now-retired Department of Natural Resources wildlife manager in Tower, used to say that a good winter for snowmobiling was a bad winter for deer.

It’s been another good winter for snowmobiling.

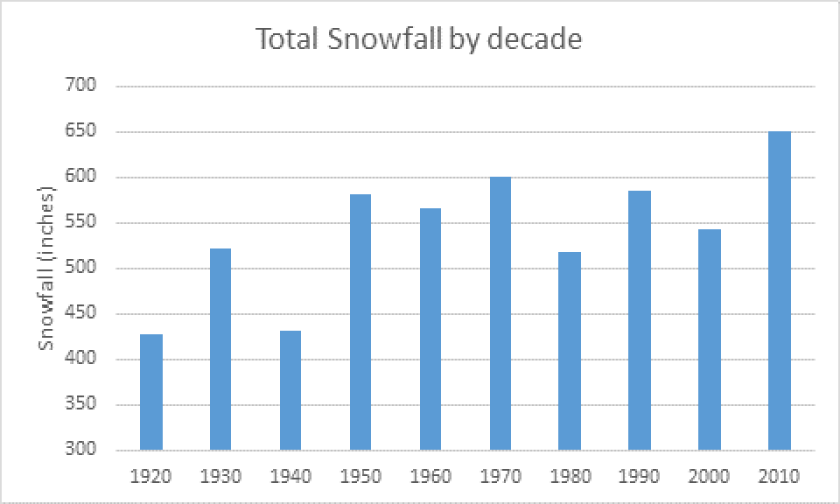

It’s starting to sound like a broken record, but the winter of 2022-23 is now the seventh winter in the past 11 — and now four of the past five — with snowfall rates exceeding the long-term average across much of Northeastern Minnesota.

Deep snow on the ground is an insidious killer of deer. They may not die suddenly, but their inability to move to new areas and find quality food gradually wears them down. They expend more energy just to survive, become weak, and are more susceptible to predation by wolves.

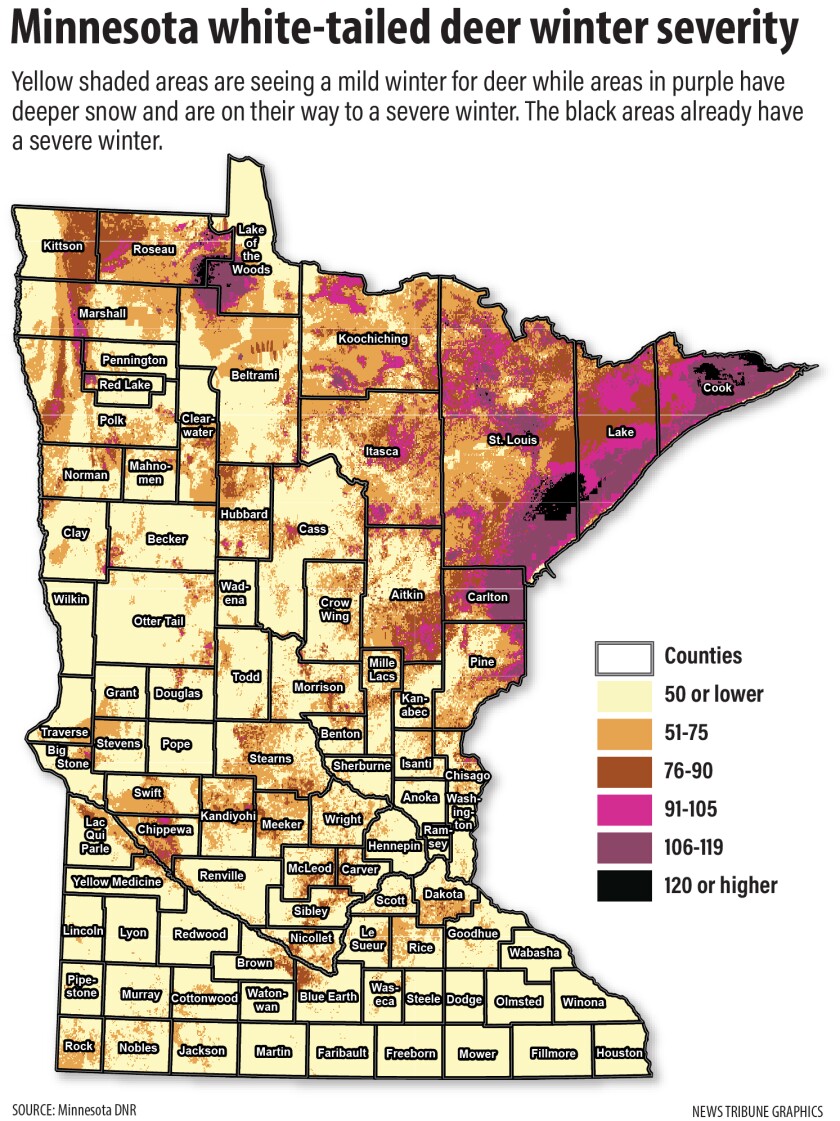

This is also the seventh winter in the past 11 when the DNR’s winter severity index for deer will climb into the severe category for large swaths of the Northland. That index awards a point for every day with 15 inches or more snow on the ground and another point for every day that sees below-zero temperatures.

ADVERTISEMENT

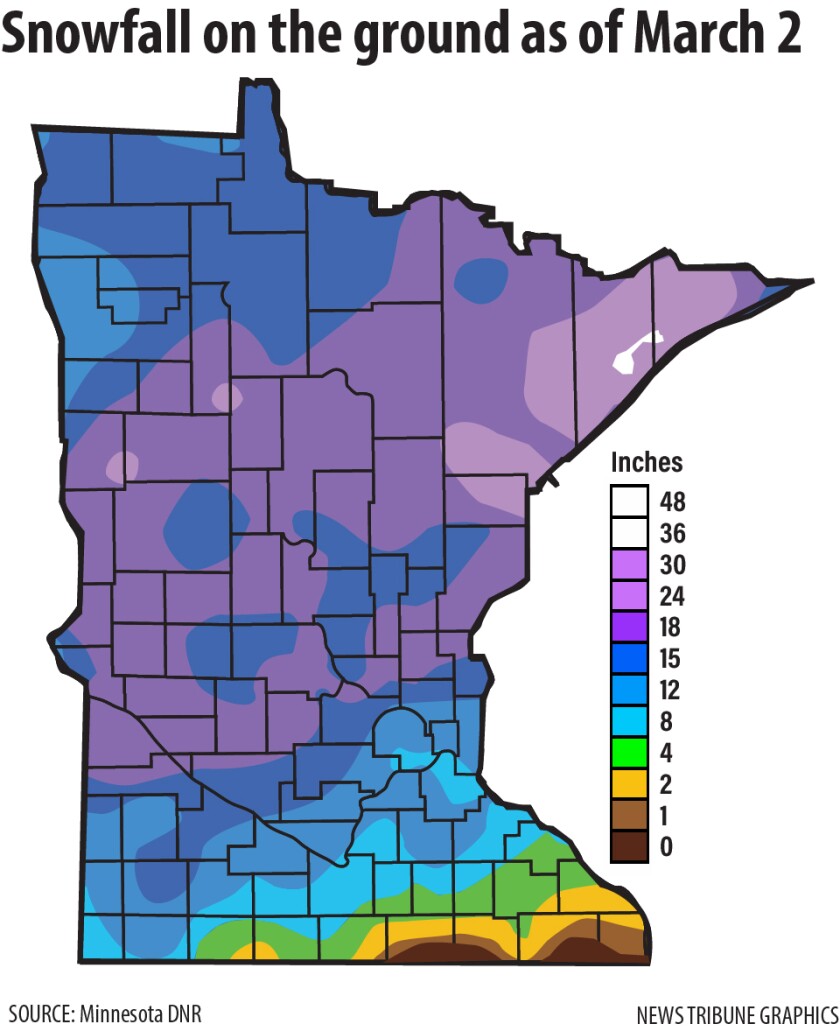

Across much of the region, there’s been at least 15 inches of snow on the ground since mid-December, and in some areas deer have been wading through twice that much snow for weeks. A few areas of St. Louis, Lake and Cook counties already have surpassed a winter severity index of 120, meaning it’s already considered a severe winter. And those numbers will likely climb much higher until snow — now 2-3 feet deep on the ground — recedes below 15 inches.

Other areas of Carlton and St. Louis and nearly all of Lake and Cook counties not already at that level are approaching 120 winter severity index levels. It’s likely those areas will see severe numbers by winter’s end.

In a normal winter about 10% of deer perish, field studies in Minnesota’s northwoods have found. In severe winters, especially if they come after mild winters, that number can jump as high as 40%.

“It really does seem that deer in that part of northern Minnesota just can’t catch a break,” said Barb Keller, big game program leader for the DNR. “It’s been several back to back years of heavy snow. And now this winter is shaping up to be the same.”

That likely will mean more areas of bucks-only hunting this autumn and fewer antlerless permits in other areas north of Duluth.

Problem diminishes quickly south, west of Duluth

While much of Minnesota has seen ample snow this winter, you don't have to go very far south and west of Duluth to find much lower winter severity indexes, and much higher deer populations, even with relatively high numbers of wolves. Those areas often receive dramatically less snow, and this year is no exception.

As of March 6, Duluth had received over 100 inches of snow this winter, while Brainerd had only 55 inches and St. Cloud had 64 inches. Duluth had 30 inches of snow on the ground, while Brainerd had 12 inches and St. Cloud just 7 inches, according to data from the National Weather Service.

Chris Balzer, DNR wildlife manager for the Cloquet/Duluth area, said the snow-depth problem gets much worse in the northern half of his work area and diminishes to the south.

ADVERTISEMENT

Deer Permit Area 132, just north of Duluth, “is one of the worst in the state. But farther south, along the I-35 corridor, things are not as tough,” Balzer said. “All of the Lake Superior snow-belt areas have had a pretty tough winter and we will probably lose some deer.”

Balzer said the crust on the snow that formed during the late-February thaw and rain is concerning.

“You might think that mild weather was helpful, but the resulting crust is allowing the wolves and coyotes to run on top of the crust. If the deer are still breaking through, then they can be vulnerable to predation in these conditions,” Balzer said, adding that wildlife managers are likely to be conservative again this year when doling out antlerless permits.

Record snowy period, relief is still months away

April, for deer, may indeed be the cruelest month. When the snow is melting and we are enjoying longer daylight and warmer temperatures, deer will still be starving. There’s almost nothing green yet in the northwoods of Minnesota. It may be well into May until they find nutritious food in the deep woods.

“It’s just before spring green-up that deer will be in their worst shape. Winter may be over by then, for us, but not for them,” Keller said. “The timing of spring green-up is really important. The later that happens, the more deer will die."

Sick and old deer drop first, followed by fawns and bucks still underweight after last fall’s rut. Adult females that are malnourished or stressed may survive but give birth to only one fawn instead of the usual two, or no fawns at all — a severe-winter’s impact that stretches for years into the future and the biggest reason the region's deer herd hasn't rebounded.

Northeastern Minnesota's Arrowhead region is seeing an unparalleled run of deep-snow winters, even snowier than those of the 1960s and '70s — back when Minnesota deer numbers were so low the DNR canceled the season entirely in 1971. It’s unclear if this trend to snowier winters is some sort of shift due to climate change or or simply random. But, of the 25 snowiest winters over nearly 150 years of records in Duluth, all of them near or above 100 inches, seven have come in the last 20 years. That already includes 2022-23.

ADVERTISEMENT

Data analysis by the U.S. Forest Service’s Northern Research Station found the 2010s to be by far the snowiest decade of the past 100 years with 650 inches of total snow in Grand Rapids. That topped the second-snowiest decade, the 1970s, by 50 inches. And the 2020s have continued to follow the same trend, with much more snow north and east of Grand Rapids.

Nearly a decade ago DNR wildlife officials set a goal of hunters across the state harvesting 200,000 deer annually. But that hasn’t happened even once, namely because the northern deer harvest continues to dwindle.

The “good ol' days” when most hunters went “up north” to find deer are long past.

“We used to have pretty even distribution of harvest across the state. ... But now, there are more deer harvested in the southern half of the state than the northern half,” Keller noted. “I don’t think we’ll ever get to that 200,000 mark unless the northern population rebounds.”

Closing season, feeding deer, won’t help

Closing the season is no longer considered an option, Keller said, because the science shows it’s not necessary. The DNR controls the harvest each year by controlling how many, if any, antlerless or doe permits are awarded to hunters. When populations fall below a sustainable level, DNR wildlife managers reduce or eliminate doe permits. And the number of bucks hunters harvest is believed to have little or no effect on the overall population. (Like pheasants or turkeys, one active male can service many females.)

“From what we know now, there’s no biological reason to close the season,” Keller said. “If it was done it would be for the public perception of trying to help. It wouldn’t help the deer population rebound any faster.”

But restricting doe permits clearly has not done enough to bring back the deer population in the north.

ADVERTISEMENT

“We’ve been pulling on that lever for some time now and we still aren’t seeing deer numbers bounce back,” Keller noted.

All of the Lake Superior snow-belt areas have had a pretty tough winter and we will probably lose some deer.

The only good news, Keller notes, is that deer densities are already so low in parts of the Arrowhead region that each severe winter’s impact is a little less fatal. Most of the old, sick and young deer already perished in past winters, and having fewer deer in the area means the remaining deer aren’t competing as much for scarce food.

“We aren’t getting reports of big numbers of dead deer being found, probably because the population already is low,” Keller said. “But that could still happen as we get later into March and April.”

Providing supplemental food for deer is also no longer considered a viable option. Follow-up studies after past, large-scale feeding efforts — the most recent in the mid-1990s — found that while feeding deer may have made some people feel like they were helping, it did nothing to increase the overall regional deer population.

Placed food can also cause deer to cross more roads and be vulnerable to vehicle collisions. And high-calorie food that deer stomachs aren’t accustomed to digesting, such as alfalfa pellets or corn, can actually harm deer, shocking their system.

“You can actually kill deer by doing that,” said Nancy Hansen, DNR wildlife manager in the Two Harbors area. “And feeding deer, concentrating them, makes them more susceptible to diseases like CWD. … And more susceptible to predators.”

With mild winters, deer can recover fast

Deer numbers can rebound fast if given a string of several mild or even normal winters in a row. That happened after several brutal winters in the 1990s, when a string of very mild winters in the early 2000s led to all-time record-high deer numbers, even as wolves also thrived.

ADVERTISEMENT

Unlike moose, with longer legs, deer didn't evolve to live this far north, where snow gets so deep — white-tailed deer only moved into the region after logging and fires opened up the forest a century ago.

Forest habitat is also a big issue, and the low-calorie food available across much of the Arrowhead — namely browse like aspen twigs — isn’t great for helping deer survive tough winters. Wildlife experts note that areas with agricultural fields offer a quicker snowmelt and faster green-up in spring and will allow more deer to survive even severe winters compared to heavily forested areas. Across North America, white-tailed deer thrive best when they have forest near farms.

Agricultural fields offer deer food later into the fall and the snow tends to melt faster offering food sooner in the spring, Balzer noted, plus better food all summer.

But habitat is not just a food issue. A decline in acres of thick, old pine, fir, spruce and cedar trees — what old timers called "deer yards" — also has hurt deer populations. Deer use areas where dense conifer stands not only mean less snow on the ground, but can actually create thermal cover — warmer conditions under the branches.

“That kind of conifer cover makes it easier for deer to move around, easier to find food and easier to escape predators,” Keller said.

DNR wildlife managers are trying to work with foresters to make sure those conifer stands are left behind when logging occurs. But once they’re gone it takes a half century or longer to get them back.

“It takes a long time to grow a tree to be big enough to provide winter cover for deer,” Hansen noted. “We’re trying to keep as much conifer cover as we can. … But spruce budworm is a big problem, killing a lot of balsam fir, which is a pretty good wildlife species, for deer and moose and hares and grouse. … We’ve lost a huge amount of balsam fir to budworm.”

Hansen said issues remain over where and how much to log older conifers but that foresters and wildlife managers are trying to work out compromises to benefit both wildlife and the timber industry.

ADVERTISEMENT

“If we did everything for (forest) management just for wildlife, yes, maybe we’d have a few more deer on the landscape right now,” Hansen said. “But with the kind of winters we have had for a decade now, it might not have made that much difference.”

Wolves matter, but not as much as deep snow

While some hunters are quick to blame wolves for the deer demise in the Arrowhead, biologists note the region had record high deer numbers, and record-high deer harvests, in the early 2000s at the same time as record high wolf populations.

While local wolf populations fluctuate, northern Minnesota’s wolf numbers have been fairly stable in recent years. And wolf numbers generally trail deer numbers: More deer equals more wolves; fewer deer equals fewer wolves.

Northeastern Minnesota had its highest-ever deer harvests in the early 2000s, peaking in 2004 when there were so many deer hunters could get bonus permits to shoot extra does. There were just as many wolves then as there are now but fewer hunters complained of wolves then because there were more deer.

Even if it would help, wildlife manager's hands are tied as far as killing wolves. They remain protected in Minnesota as threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act, meaning hunting and trapping are prohibited.

“It’s not an option for us at this time,” Keller said. “But, even if it was, a wolf season wouldn’t bring the deer back on its own.”