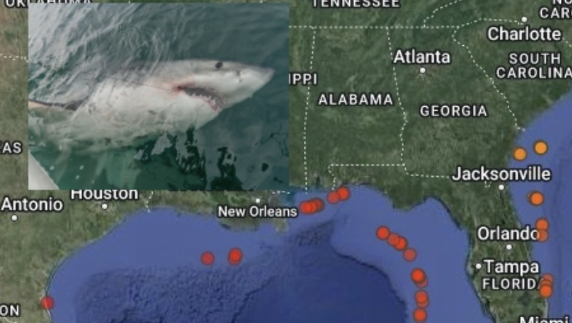

LeeBeth, a 14-foot great white shark, has been moving along the Gulf Coast between Louisiana and Texas.

A camera attached to the shark captured her off the coast of Louisiana on February 16 and 17. LeeBeth then went west toward Texas, ventured south and appears to be coming back.

Now, a month later, the shark pinged west of Breton National Wildlife Refuge, according to the Sharktivity app Sunday. The refuge is located off the eastern coast of Louisiana and the western coast of Biloxi.

Since getting her tracking device from the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy in December, LeeBeth has traveled more than 2,000 miles south and into the Gulf of Mexico, the scientists tracking her said Monday.

Researchers watched as she made history in late February by traveling further into the Gulf than any previously tracked white shark. A signal showed her off the coast near Matamoros, Mexico, which is just across the border from South Padre Island, Texas.

The shark's presence so far west indicates that this part of the Gulf of Mexico could also be important to other white sharks, said Megan Winton, a senior scientist with the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, based in Chatham, Massachusetts. International cooperation is important to protect the sharks, which are recovering worldwide their populations after suffering from overfishing for decades, she said.

“We don't know how many white sharks travel that far west, but it's a good indication they do,” Winton said. “There are only a handful of sharks that have been tracked west of the Mississippi.”

LeeBeth is the first great white off the southeast coast to be tagged with a camera tag, which allows researchers to view footage taken from her dorsal fin.

That camera transmitted some footage that you can see here in early February. The camera tag typically falls off after several days.

The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy collaborates with Massachusetts state government to tag white sharks, and more than 300 have been tagged so far. Thousands more have been tagged by other organizations worldwide, Winton said.

The conservancy paired up with fishing charter Outcast Sport Fishing of Hilton Head, South Carolina, to tag LeeBeth.

Chip Michalove, who owns Outcast, said LeeBeth turned out to be an advantageous shark to tag, as she had sent more signals back from the tracking device than most. The tracker sends a signal when the shark breaks the surface of the water.

“Not only one of the biggest sharks we've caught, but she's the best-pinging shark as well,” Michalove said. “We definitely hit a home run with LeeBeth.”

Although reasonable to feel frightful of LeeBeth off the coast, the Houston Chronicle came up with a list of other dangers statistically more likely to impact beachgoers this year.

The last time LeeBeth checked in was on March 7, when tracking data showed her about 100 miles (160 kilometers) off the coast of Galveston, Texas. The tracking device on LeeBeth is called a "SPOT," which stands for smart position or temperature. The device sends signals to overhead satellites when the shark sticks its tagged fin above the water.

You can monitor LeeBeth's movements via the Sharktivity app.

Two other great white sharks have been tracked in Louisiana waters this year. Both Keji (a 10-foot long, 600-pound juvenile male) and Crystal (a 10-foot long, 460-pound juvenile female) were tracked by OCEARCH close to the Mississippi coast.