As Colorado marks another COVID-19 anniversary, the takeaway for historians and epidemiologists is as simple as it is jarring: Americans haven't learned the lessons from history.

Three years ago Sunday, Colorado reported its first COVID-19 case — a 30-something male skier who had traveled to Italy.

Eight days later, on March 13, an El Paso County woman in her 80s with underlying health conditions became the first in Colorado to die from the novel coronavirus. At the time, Colorado had 77 known cases.

In the days that followed, public health and executive orders shuttered businesses and schools; canceled nonessential surgeries; limited evictions and foreclosures; required face masks in public and shut-in Coloradans with stay-at-home orders.

The headlines could have been written 100 years ago.

“All the same things used today were used back then,” said J. Alexander Navarro, a University of Michigan historian who has extensively studied the Spanish flu of 1918.

After a dozen military trainees caught a deadly strain of the Spanish flu in the fall of 1918, City Manager of Health and Charity and former Denver Mayor Dr. William H. Sharpley set up an advisory board. He also instructed residents to avoid crowds, cover coughs and sneezes and to seek a physician if cold-like symptoms developed.

When the number of cases and deaths climbed, Sharpley ordered hospitals to isolate influenza patients. School closures, assembly bans and business restrictions followed, which included prohibiting funerals.

What happened next now seems all too predictable.

Cases dipped and public health officials lifted the mitigation measures. In an unfortunate coincidence, the day the mitigation measures were lifted in Denver, a throng of residents poured into the streets to celebrate the armistice and end of World War I.

A week later, Denver was in the throes of a surge with hundreds of new influenza cases and dozens of deaths.

Sharpley blamed the public.

“It is not the lifting of the closure ban that is the cause of spreading of the epidemic, but the putting aside of all the precautions and restrictions by the people of Denver when they celebrated on Victory Day,” Sharpley said.

‘Another resurgence’

What made the Mile High City so interesting to researchers like Navarro is that Denver was one of a few that had intervened and then walked back mitigation measures for which the public had grown weary.

“The pandemic wasn’t over,” Navarro said. “Almost immediately we saw another resurgence of cases.”

As a result, the Spanish flu pandemic droned on for months with a second deadly spike becoming one of the nation’s largest death tolls, per capita.

City officials responded with a mask order and shutting down amusement businesses. But enforcement was fraught with complications from the public refusing to wear masks to business owners complaining they had been unfairly singled out.

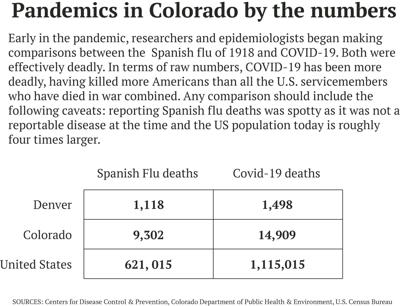

The deadliest pandemic of the 20th century, the Spanish flu killed roughly 9,300 Coloradans and more than 1,100 in Denver.

Denver’s response to the Spanish flu, Navarro argued, illustrates what happens when people don’t follow public health orders — or when strong leadership is lacking.

“Public health doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” Navarro said.

In 2007, Navarro and a team of researchers studied the interventions 43 cities — including Denver — implemented to curb the spread of the Spanish flu. Their study found “early, sustained and layered” interventions mitigated the consequences of the pandemic.

“In planning for future severe influenza pandemics, nonpharmaceutical interventions should be considered for inclusion as companion measures to developing effective vaccines and medications for prophylaxis and treatment,” the authors wrote.

To date, COVID-19 has killed 1.1 million Americans; nearly 15,000 Coloradans and roughly 1,500 Denverites.

“It was frustrating seeing history repeat itself,” Navarro said.

‘The public respected the pandemic’

There are key differences between the Spanish flu and COVID-19, which has killed more Americans than those who died in all the U.S. wars, combined.

Reporting 100 years ago was spotty. No central agency existed to control the outbreak (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wasn’t formed until 1946).

Another notable difference was who the disease killed.

With COVID-19, older Americans and those in congregate settings, particularly nursing homes, bore the brunt of the deaths while healthy 20-to-40-year-olds had an unusually high mortality rate with the Spanish flu.

“The 1918 flu killed people mainly in the prime of life,” Metropolitan State University of Denver History Professor Stephen Leonard said.

Leonard added: “In a way, the societal impact was almost greater.”

The duration of the pandemics also differed with the Spanish flu running from 1918-1919. COVID-19 is now entering its fourth year, although President Joe Biden announced he will end the emergency declaration in May.

And while the public pushed back on some of the mitigation strategies, the Spanish flu — the first global pandemic in the era of mass society — was not politicized as COVID-19 has been.

“The public respected the pandemic, it was almost never politically motivated,” Navarro said.

Leading experts said the irony is that the best measures to control highly infectious diseases like the Spanish flu and COVID-19 — public gathering bans, school and business closures, face masks and quarantines — are precisely the most difficult to implement in a mass society.

These measures remain highly controversial even today, with some contending that the school closures unnecessarily set back students’ learning, when they are the least susceptible to the virus, and the lockdowns separated families, particularly older residents, who ended up dying alone in hospitals or facilities without their loved ones.

Critics also claim that health authorities had been inconsistent, first saying face masks were not needed and then concluding they were or insisting the vaccine would prevent catching the virus but later saying it would minimize the severity of the symptoms, rather than eliminate the chances of getting sick.

‘Preparing for the next pandemic’

Researchers will likely study the COVID-19 pandemic for decades to come.

They said while some of the lessons will take time to unfold, others are fairly clear now: better surveillance is critical; international cooperation is necessary and work rebuilding the public trust in public health, essential.

“I think the takeaway is we have a lot of work to do preparing for the next pandemic,” said Navarro, of the University of Michigan. “Because it’s a matter of when, not if.”

Dr. Michelle Barron, senior director of infection prevention at UCHealth, agreed.

Despite the missteps, Barron said she believes history will reflect well on the scientific achievement, creating an effective vaccine in record time.

“Science matters,” Barron said. “But it’s got to be good science.”