America’s Last Morse-Code Station

Maritime Morse code was formally phased out in 1999, but in California, a group of enthusiasts who call themselves the “radio squirrels” keeps the tradition alive.

“Calling all. This is our last cry before our eternal silence.” With that, in January 1997, the French coast guard transmitted its final message in Morse code. Ships in distress had radioed out dits and dahs from the era of the Titanic to the era of Titanic. In near-instant time, the beeps could be deciphered by Morse-code stations thousands of miles away. First used to send messages over land in 1844, Morse code outlived the telegraph age by becoming the lingua franca of the sea. But by the late 20th century, satellite radio was turning it into a dying language. In February 1999, it officially ceased being the standard for maritime communication.

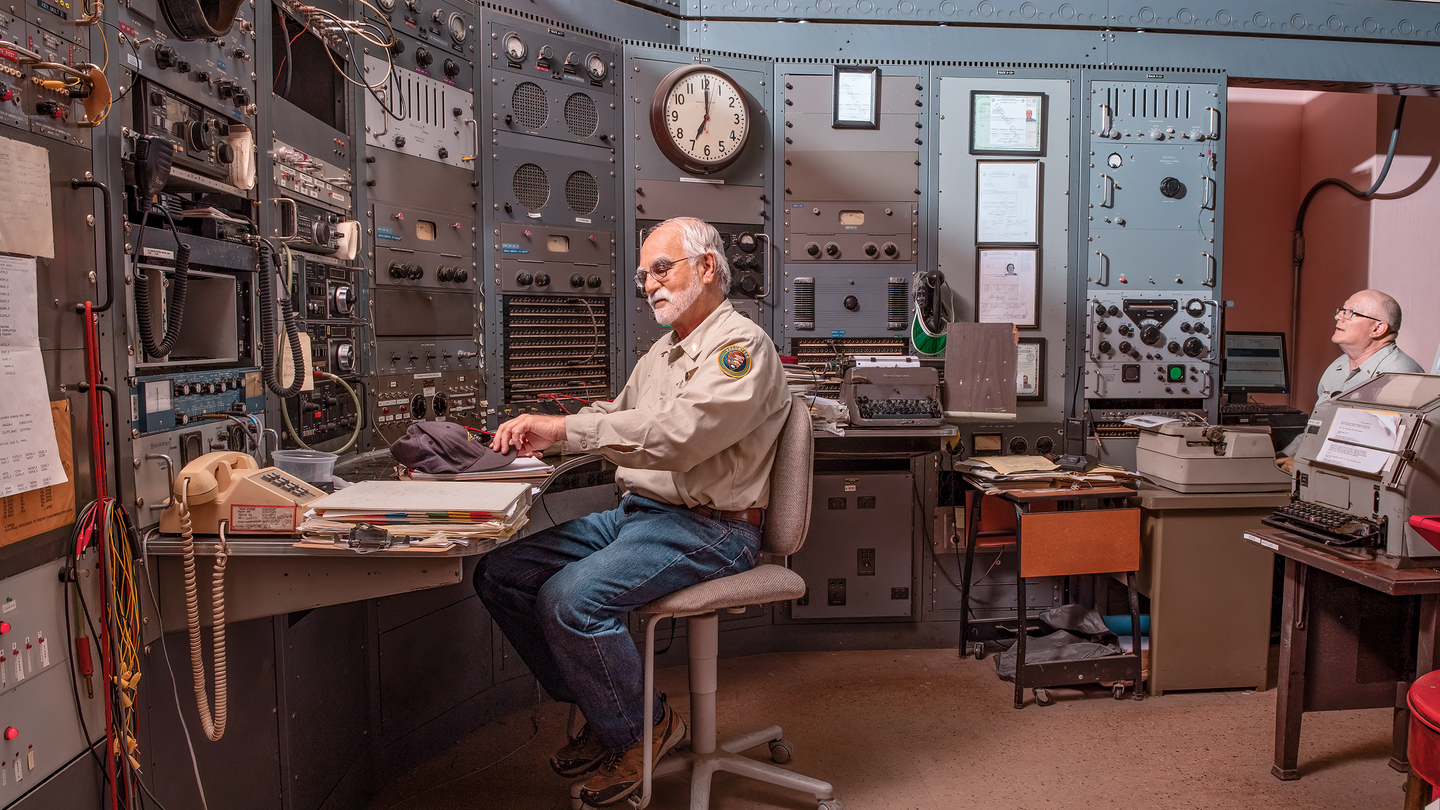

Nestled within the Point Reyes National Seashore, north of San Francisco, KPH Maritime Radio is the last operational Morse-code radio station in North America. The station—which consists of two buildings some 25 miles apart—once watched over the waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Both KPH sites shut down in 1997, but a few years later, a couple of radio enthusiasts brought them back to life. The crew has gotten slightly larger over the years. Its members call themselves the “radio squirrels.” Every Saturday, they beep out maritime news and weather reports, and receive any stray messages. Much of their communication is with the SS Jeremiah O’Brien, a World War II–era ship permanently parked at a San Francisco pier.

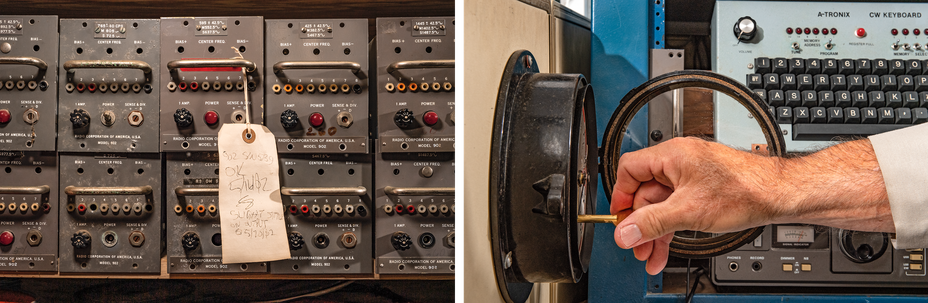

Last July, the photographer Ann Hermes visited the radio squirrels and stepped into their time machine. To send a message, they tapped each Morse-code letter into a gadget called a “bug,” generating a loud, staticky noise that reverberated throughout the whole building. “It’s almost like jazz,” Hermes told me—a music of rhythm and timing that can sound slightly different depending on who is doing the tapping.

Some of the hulking machines date back to World War II. The squirrels do their own repairs, and scrounge eBay for replacement parts on the newer units. To honor the station’s past, the volunteers start each Saturday morning with “services” for “The Church of the Continuous Wave,” in which they eat breakfast off vintage plates branded with the Radio Corporation of America’s old logo.

Morse code is not quite extinct: The U.S. Navy still teaches it to a few sailors, and in 2017, a British man who had broken his leg on a beach used it to signal for help in the dark with a flashlight. Many of the radio squirrels are retired or nearing retirement. But when Hermes visited over the summer, she spotted one 17-year-old hovering around the squirrels in action. Born after the effective end of Morse code, he was nonetheless eager to help keep the jazz going.

This article appears in the April 2024 print edition with the headline “The Radio Squirrels of Point Reyes.”