Wave of innovation aims to make desalination sustainable

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the grip of a three-year drought, the Spanish city of Barcelona announced last month that it would have to start supplying its 1.6mn inhabitants with water brought by boat from a desalination plant in the nearby Valencia province from June this year.

Shipping water by sea is an expensive solution — as is the desalination process that distils the water. But the decision underscores the severity of the drought. Now, Catalan authorities are planning to double the region’s capacity for desalination over the next three years.

Spain is not the only country to view desalination as a potential solution to water shortages. Although just 1 per cent of the world’s water currently comes from desalination, governments in the US, Egypt, Morocco and Italy all have plans to expand plant capacity.

“The big advantage of desalination is that seawater is plentiful and it’s usually available where fresh water is needed most,” says Christopher Gasson, owner of information provider Global Water Intelligence — noting that demographic growth is fastest in the world’s coastal mega cities. “Almost every other source of drinking water is ultimately dependent on enough rain falling in the right place,” he points out.

Saudi Arabia, which already obtains 70 per cent of its water from desalination, is expanding production while, in the US, the Biden administration has allocated $250mn to desalination projects. In Egypt and Morocco, renewable-powered plants that can produce drinking water and irrigate crops are being built.

There are downsides. Desalination is an energy-intensive process, which has mostly relied on fossil fuels. And dumping its super-salty brine byproduct back into the sea can pose a risk to marine life, environmentalists warn. This is particularly true if antiscalants and cleaning chemicals are discharged with the brine.

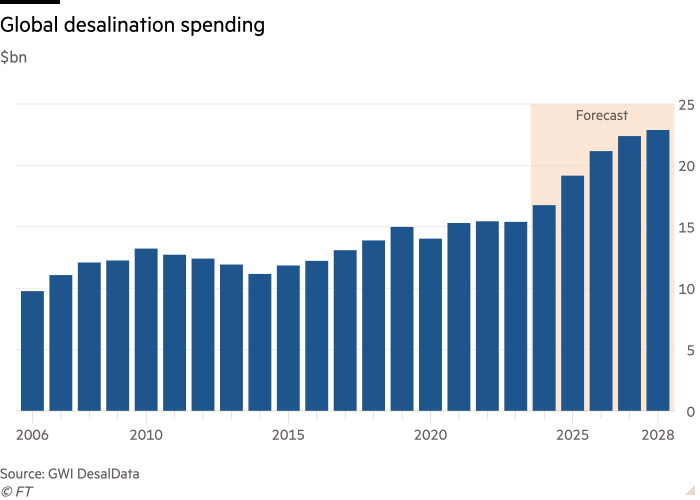

However, a wave of innovation is starting to make desalination plants more environmentally friendly and cheaper to power in sunny and water-stressed areas. According to GWI’s research, desalinated seawater production will rise from 45mn cubic metres per day now to 61mn cubic metres per day in 2027 — enough to supply 400mn people per day.

There are already 186 facilities under construction, or in their design phase, mostly in the Middle East and north Africa, according to GWI. The two regions currently account for about half of all the world’s desalinated water production and are investing billions in new infrastructure.

Even in the much wetter UK — which nevertheless suffered droughts in 2022 — utility company South West Water has one desalination plant on the Isles of Scilly, and is planning another in Cornwall, with the aim of supplying customers by December 2024. Thames Water, the country’s largest water provider, also has a desalination plant, though it has mostly not been used because of high energy costs.

Energy accounts for between one-third and just over half of the total cost of desalinated water. But Gasson says the availability of low-cost solar power is driving a revolution in the industry. On February 29, a Saudi developer closed the financing of Dubai’s Hassyan desalination plant at a record low tariff of $0.36 per cubic metre — a feat made possible by the availability of solar power in the emirate priced at less than $0.02 per kWh.

Now, competition between Gulf states to reduce the cost of desalinating seawater further is hotting up. Last year, Saudi Arabia’s Saline Water Conversion Corporation launched a $10mn global prize for Innovation in Desalination. This was topped on March 1 this year by the announcement that the UAE’s Mohamed bin Zayed Water Initiative had provided $119mn to support the XPrize Water Scarcity competition.

The main focuses of innovation, Gasson says, are new materials for the membranes that filter out salt, improved integration of renewable energy, digital systems for monitoring and control, the recovery of valuable minerals such as lithium and rare earth metals from the brine stream, and better control of membrane scaling and fouling. Recent breakthroughs include new self-cleaning membranes that prevent the accumulation of scale.

Companies are hoping to find multiple ways to make desalination more efficient without boosting carbon emissions. UK-based Core Power, for example, is developing nuclear-powered offshore plants, while Canada-based Oneka is harnessing wave power for floating desalination units.

Others, such as Norway’s Flocean Desal, are designing desalination technology that can work on the seabed, which, it argues, reduces impact on the marine environment and is less energy-intensive.

But not everyone is happy with the drive towards desalination. Many believe it should be only a last resort, and that conservation, recycling, and capturing stormwater are better options. That applies in Barcelona, too, where Greenpeace has called for better water management policies.

Fernando Fernández of Greenpeace, in Catalonia, says: “We need policies that reduce our consumption in large sectors such as agro-industry and tourism, instead of continuing with business as usual.”

Comments