Just Press Print

As epoch-making as Gutenberg’s printing press, 3-D printing is changing the shape of the future.

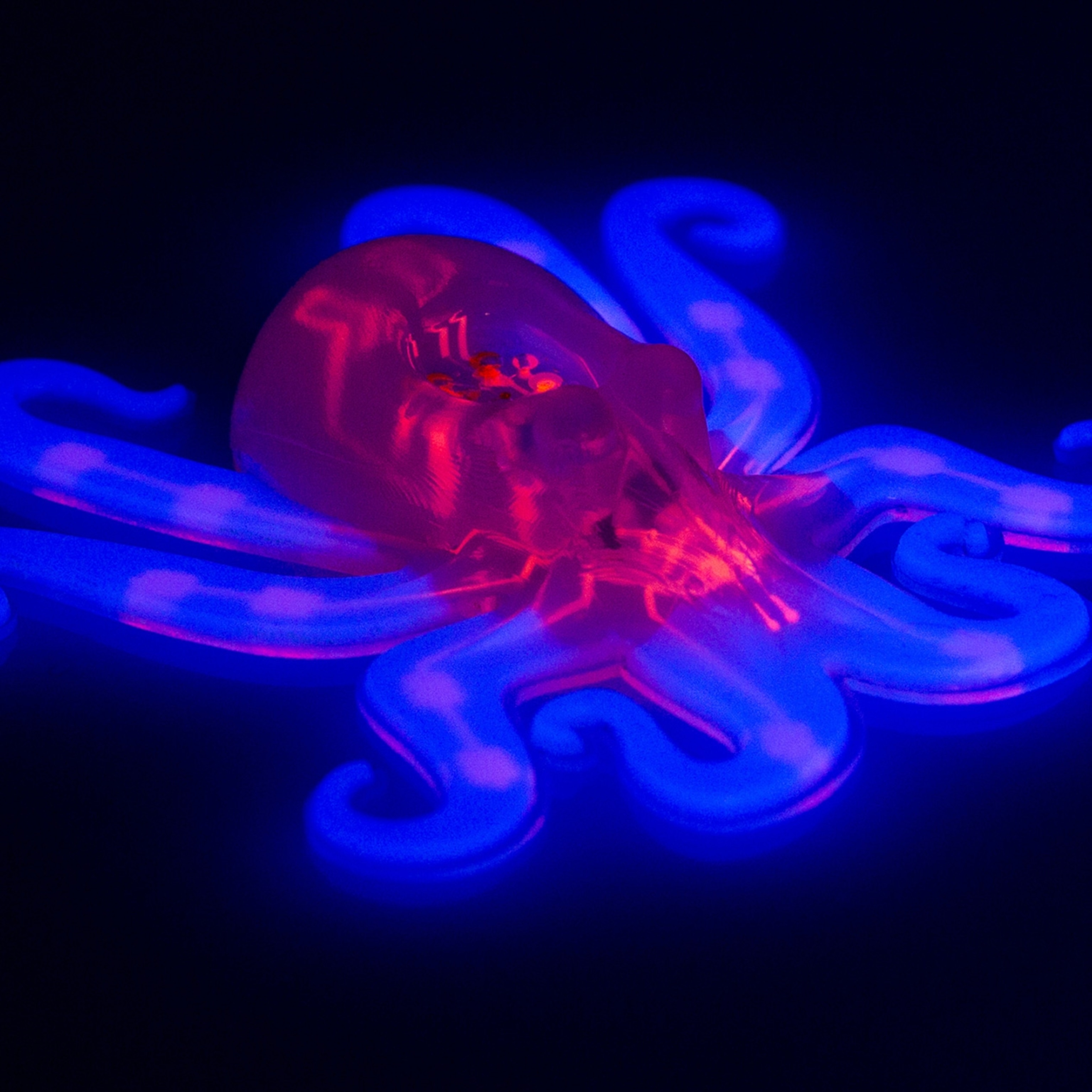

Rocket engine parts, chocolate figurines, functional replica pistols, a Dutch canal house, designer sunglasses, a zippy two-seater car, a rowboat, a prototype bionic ear, pizzas—hardly a week goes by without a startling tour de force in the rapidly evolving technology of three-dimensional printing.

What sounds like something out of Star Trek—the starship’s replicator could synthesize anything—is increasingly becoming a reality. Indeed, NASA is testing a 3-D printer on the International Space Station to see if it might provide a way to fabricate meals, tools, and replacement parts on long missions.

Back on Earth, long-term business plans are being reimagined. Airbus envisions that by 2050 entire planes could be built of 3-D printed parts. GE is already using printers to make fuel-nozzle tips for jet engines. And interest isn’t limited just to corporate giants.

“We all know that 3-D printing is going to play a big role in the future,” says Hedwig Heinsman, one of the partners in the Dutch architectural firm DUS, which is printing a house on the banks of Amsterdam’s Buiksloter Canal.

Over three years a 20-foot-tall printer, the KamerMaker (Room Maker) will create walls, cornices, and rooms, trying out materials, designs, and concepts. “I can see a time coming where you will be able to choose and download house plans like you were buying something on iTunes, customize them with a few clicks on the keyboard to get just exactly what you want, then have a printer brought onto your site and fabricate the house,” adds Heinsman.

Additive manufacturing—as 3-D printing is also called—has been around for about 30 years. It’s the quick pace of advances that has created the recent buzz and inspired some grandiose predictions. But there is a huge and possibly unbridgeable gap between what can be made on highly sophisticated commercial 3-D printers and what you can make on a home printer. A 3-D printer works in much the same way as a desktop printer does. Instead of using ink, though, it “prints” in plastic, wax, resin, wood, concrete, gold, titanium, carbon fiber, chocolate—and even living tissue. The jets of a 3-D printer deposit materials layer by layer, as liquids, pastes, or powder. Some simply harden, while others are fused using heat or light.

The high cost of tooling up a factory has long been a barrier to developing niche products. But now anyone with an idea and money could go into small-scale manufacturing, using computer-aided design software to create a three-dimensional drawing of an object and letting a commercial 3-D printing firm do the rest.

Since a product’s specifications can be “retooled” at a keyboard, the technology is perfect for limited production runs, prototypes, or one-time creations—like the one-third-scale model of a 1964 Aston Martin DB5 that producers of the James Bond filmSkyfall had printed, then blew up in a climactic scene.

And because a 3-D printer builds an object a bit at a time, placing material only where it needs to be, it can make geometrically complex objects that can’t be made by injecting material into molds—often at a considerable savings in weight with no loss in strength. It can also produce intricately shaped objects in a single piece, such as GE’s titanium fuel-nozzle tips, which otherwise would be made of at least 20 pieces.

This same precision is making it possible to fabricate things never before made. A team of Harvard University researchers has printed living tissue interlaced with blood vessels—a crucial step toward one day transplanting human organs printed from a patient’s own cells. “That’s the ultimate goal of 3-D bio-printing,” says Jennifer Lewis, who led the research. “We are many years away from achieving this goal.”

Additive manufacturing is much slower than traditional manufacturing, but that could change, says Hod Lipson, a professor at Cornell University long involved with 3-D printing.

“Printer speed, resolution, and the range of materials that can be printed are all being developed right now, along with printers that are capable of printing with multiple materials and creating objects with working parts and active circuitry,” Lipson says.

He and his team printed a replica of Samuel Morse’s telegraph. With a nod to history, they tested it by tapping out the message an awed Morse sent in 1844: “What hath God wrought?”

God may have wrought the principles, but people are pressing the buttons. In May 2013 a political activist named Cody Wilson grabbed headlines when he announced the test-firing of the world’s first 3-D printed handgun, the Liberator, a single-shot .38-caliber pistol made with $60 worth of plastic.

The news initially unnerved law-enforcement officials, who foresaw disposable, untraceable guns printed like term papers. But making a reliable gun is not simple—or cheap. When a California firm, Solid Concepts, printed a limited edition of a hundred Browning Model 1911 .45-caliber pistols, it did so with a printer and facilities that cost the better part of a million dollars.

“It’s simply a lot easier for crooks to get hold of a gun the old-fashioned way—buying them or stealing them—than to fuss over a 3-D printer for a couple of days, only to end up with a warped plastic blob or, even worse, something that blows up in their hands,” says Jonathan Rowley, design director of Digits2Widgets, a London 3-D printing firm that made the parts of a nonworking version of Wilson’s gun for the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Few people will be crushed by not being able to print a Saturday night special, but many may be disappointed with the misshapen trinkets that are the typical fare. “People read about the fabulous things that are being made with 3-D printing technology, and they are led to believe that they will be able to make these things themselves at home and that what they turn out will be of a really high standard of workmanship,” Rowley says. “It won’t be.”

While consumer printers may one day allow us to make whatever we like, Rowley envisions a different grassroots revolution, one where people can test ideas that once would never have made it off the back of an envelope.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

Environment

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?When treasure hunters find artifacts, who gets to keep them?

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- When America's first ladies brought séances to the White HouseWhen America's first ladies brought séances to the White House

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

Science

- Quieting your mind to meditate can be hard. Here’s how sound can help.Quieting your mind to meditate can be hard. Here’s how sound can help.

- Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?Should you be concerned about bird flu in your milk?

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

Travel

- Photo story: a water-borne adventure into fragile AntarcticaPhoto story: a water-borne adventure into fragile Antarctica

- Germany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see itGermany's iconic castle has been renovated. Here's how to see it

- This tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramidThis tomb diver was among the first to swim beneath a pyramid

- Food writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavoursFood writer Dina Macki on Omani cuisine and Zanzibari flavours